If Alex Graham's Angloid is not even semi-autobiographical, I am probably being straight-up rude for assuming it is. The protagonist drinks too much, smells bad, and propositions much older men only to then face the further indignity of being laughed off. She is not the quietly wary observer of the world found in most autobiographical comics. She is more the sort of character that would show up in the margins of someone else's story, kept at a distance for the sake of safety, like the "crazy friend" in a Mary Fleener comic. However, there are things in the presentation of the book, recently republished by Kilgore Books after a small self-published print run, that highlight parallels between author and subject: There are photos of the author and the gallery that represented her in Denver from a few years ago, and the book is about an artist in Denver who is seemingly the only client represented by a struggling gallery. Obviously, viewing a work of fiction as autobiographical presents the reader with a certain voyeuristic thrill, but I'm not interested in that type of reading. The choices that Alex Graham makes turn Angloid into a more interesting book if you view it as being partially autobiographical for completely different, and fairly unique, reasons.

Angloid was originally serialized in a self-published series called Cosmic Be-Ing. You can order issues from Domino Books. I recently ordered issue number 3, not included in the Angloid collection, but drawn during the same time period. While you can view Cosmic Be-Ing as a one-person anthology in the vein of Eightball or Dirty Plotte or Pope Hats, it's worth noting that it has recurring characters, the titular Cosmic Be-Ings. They host the book, in the manner of EC's Crypt Keeper, or the cartoon avatars of Daniel Clowes and Julie Doucet. They exist outside of human bodies, but can observe our plights and feel sympathy for us, even as they view these bodies as something of a mask for all of life's innate one-ness and god-nature, which they are closer to. Issue 3 focuses on these creatures, with one attempting an incarnation on Earth, blessed with Godlike powers, in order to enlighten humanity and end suffering. These characters narrate Angloid as well, and at times intervene in the plot, usually when the title character gets too close to acting on her suicidal ideation.

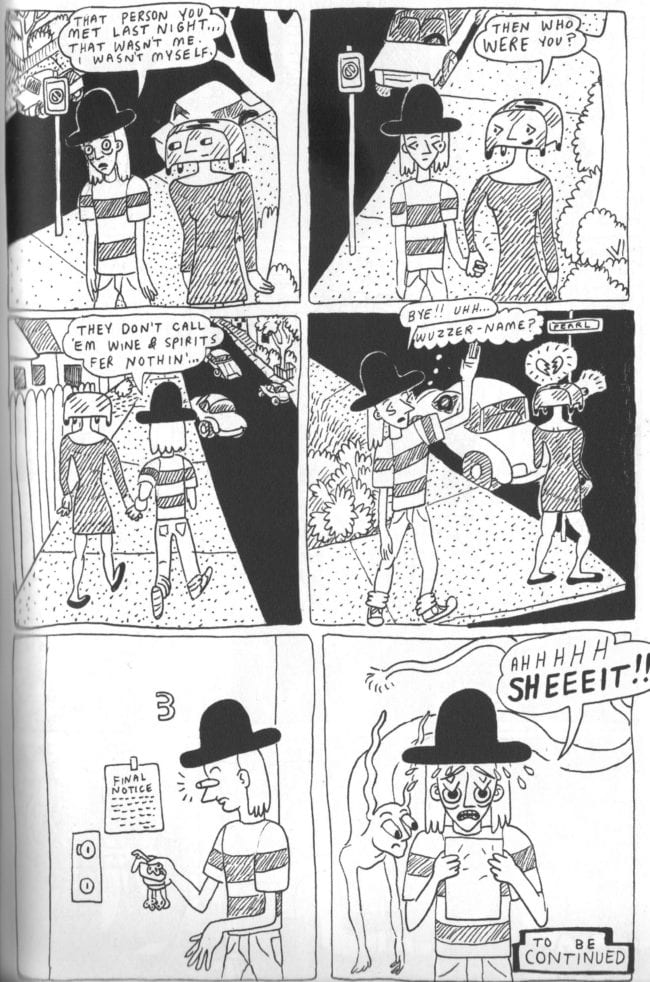

The Be-Ings' perspective, delivered in comics sequence as monologues captioned as being "channeled," is probably not that foreign to you. It's familiar from religious (or New Age) thought, and fits the description most associated with the catch-all term "spirituality." However: If we view this framework as being the author's actual worldview, and Angloid as being an autobiographical character, than this comic documents times when the author recognized spirits intervening in her life. The comic's splitting of its authorial perspective essentially creates an oblique schizophrenia memoir, where the awareness of the spiritual dimension of life occurs on a parallel track to the life of someone who drinks too much and can't maintain healthy relationships. (I should point out my own understanding of schizophrenia is largely defined by this essay my friend wrote for Mask Magazine. It's mostly paywalled, but even the opening, which is readable to all, is useful.) In-story, the character is rarely aware of these mystic interventions, but when she is, there are scenes that can be read as approximating magic realism, or alternately understood as total psychotic breaks. However, it's all totally underplayed; never changing its visual register to accommodate a subjective fantasia, always speaking this alt-comics argot of thin lines and relatively unlabored rendering, though compositions are consistently varied to maintain interest. It's a language where the non-realistic inserts itself as comedy, like a "sex scene" where Angloid plugs in a toaster-headed women, a bit that further works to short-circuit any salacious voyeurism a reader might attempt.

This visual language feels like a direct communication method, in the manner of the "letter from a friend" feeling you get from a certain type of zine, but also seems to contain a degree of objective distance, which seems related to the Be-Ings' observational perspective. The comedic tone is closer to what you see in screwball comedy than the essayistic intimacy that defines the sense of humor you normally get from people writing about themselves. The voice is neither self-righteous nor self-deprecating. It never feels like Alex Graham is trying to score points of sympathy with the reader for the way people mistreat her theoretical stand-in. There's a sequence where a boy Angloid dates plays in a rock band with lyrics that can be interpreted as misogynist, lamenting a girl with "daddy issues," but the book never highlights this as villainous: If you see it that way, there's a joke there, but the neutrality of the storytelling seems to understand why a dude that dates Angloid might have reason to be wary and judgmental. Even Angloid, in the book's early pages, dismisses her gallerist's concerns about his own unhealthy lifestyle with "Yer talkin' schizo now… that's my cue to leave." The chapter about the boyfriend in a band ends with Angloid saying something that that could be interpreted as totally bleak suicidal ideation, although the dude just views it as a joke. Maybe he's emotionally checked-out to the point of cruelty, or maybe he understands that Angloid is in fact joking. In the context of the comic, it's basically both, while a more heavy-handed work would make a big thing out of one fixed reading of the moment. In another sequence, a person Angloid works with tells her he heard she's been smoking crack with another coworker, and while Angloid denies this, there's never narration reinforcing that denial, which makes it read like she could've smoked crack, and the coworker she's hanging out with probably has, but it wasn't included in the pages drawn. The reader exists in the framework of the alien observer, rather than the protagonist's memory.

The lack of omnipresent narration means there is no voice insulating the main character from her experiences, reassuring the reader that everything is okay and an observational anthropological perspective will be maintained. This is the reality of people with mental health troubles, that's totally absent from the sort of "I'm so neurotic" memes I see proliferating among the relatively affluent. The form of memoir, which seems comparatively luxurious, as most people never get such chances to narrate their own life and present themselves sympathetically, is bypassed entirely. The comic is probably more effective and realistic at telling a story about mental health than something that explicitly aims to be about that subject. It feels like someone just telling you about their life, though the subtext feels palpably dire.

Ignoring the subtext, the book should still be relatable to a wide swath of its likely readership, as much of it concerns a young artist attempting to get a job she can live off of, while still being able to make art. She finds work waitressing by playing up her figure, wearing makeup, avoiding anyone who knows her past, and suppressing her natural style. This gender presentation attracts its own troubles, in the form of sexual harassment from men and judgment from women. Before this development, the book's first chapter is pretty ambiguous about what gender Angloid is. It's only in the second, when she laments being "trapped in this female flesh prison," that readers know for sure. The character's awareness of life's spiritual dimensions defines her, but is ignored and unappreciated by those around her.

It's not even necessarily about "mental health." The splitting of the authorial voice also suggests that in our current cultural vernacular, we are more forgiving or understanding of acting out, bad behavior, and self-destructive alcoholism than we are of mysticism and viewpoints that do not prize the rational as the highest value. The book's structure, as an account of a life, never feels like a simplistic parable or fable, the way attempts at imparting spirituality often do. It's not that the book is walking a line between the spiritual and the abject, so much as walking all around the territory of a life to explain that the idea of a border between the two is false. The book's implicit arguments are multiple. Any ideas about the nature of life on Earth and societal interaction with the individual are presented via ideas about comics as a direct form of communication, and while none of these by themselves are unique, being put together in a holistic way makes for an intriguing book, that compels the audience past its understated surface to reward those who really read it.