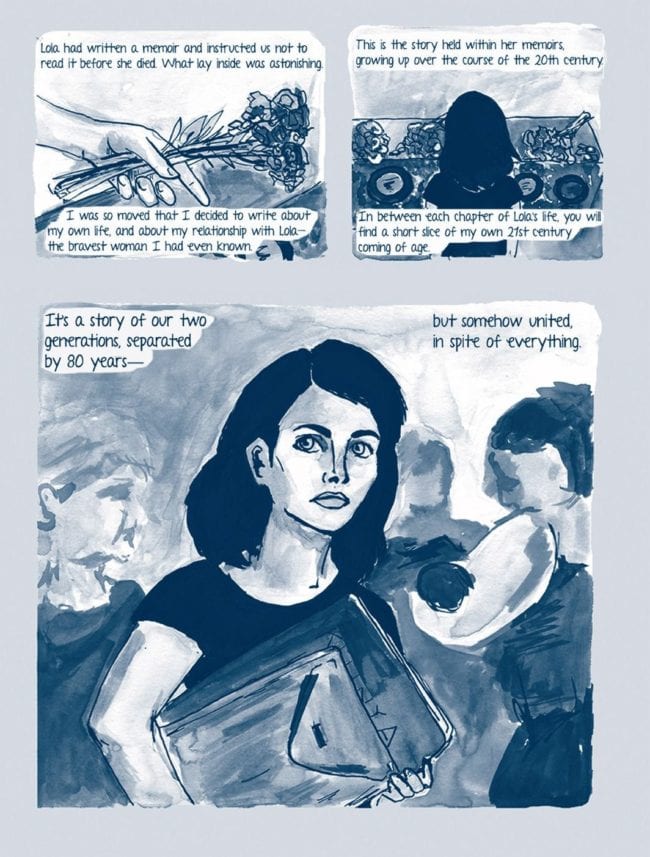

The subject of Julia Alekseyeva's biographical comic Soviet Daughter, her great-grandmother Lola, left her life savings to her great-granddaughter. However, Alekseyeva's real inheritance was Lola's memoir, which she instructed her family not to read until she died. Khinya "Lola" Ignatovskaya was born in 1910 and lived through the Soviet revolution in her native Kiev. A first-person memoir of an average citizen who lived through the twentieth century and beyond (she died at the age of a hundred) is interesting enough on its own, but a memoir of Soviet Russia from the point of view of a Jewish woman is especially fascinating. Alekseyeva ties Lola's narrative to hers, bluntly stating that she never felt close to any family members except her great-grandmother. She weaves autobiographical interludes between chapters of Lola's story, creating a tapestry that unites the narratives of two kindred spirits.

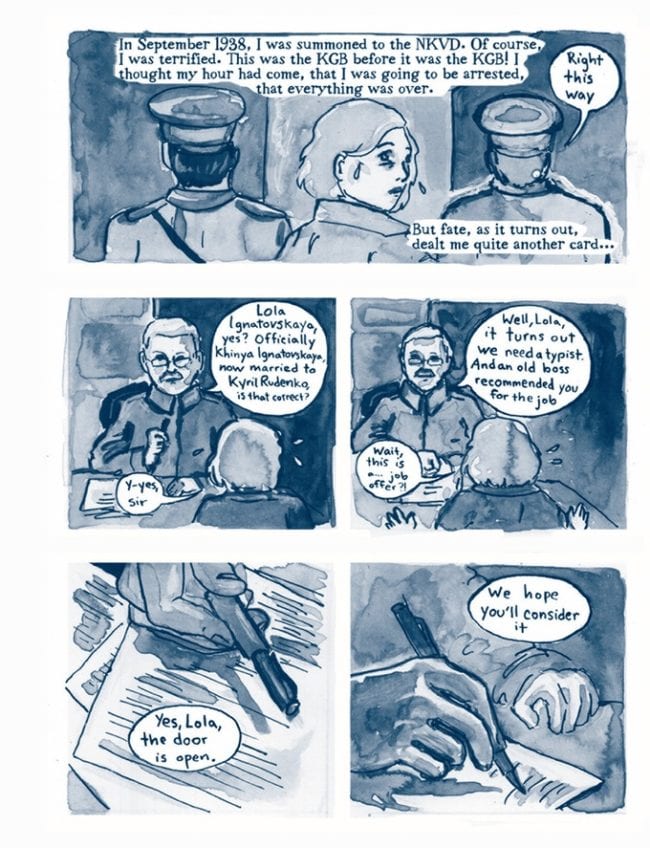

One reason why zigzagging back and forth between Lola's memoir and Alekseyeva's own story works so well is that both narratives are those of young iconoclasts. Lola talks in blunt language about her poverty-stricken upbringing and her fierce desire for independence. Growing to adulthood in 1920s Soviet Union meant that as a woman, she had greater overall equality than at any other time in history. This is not to say that sexism disappeared, but rather that the official factories paid men and women about the same wage and women had the freedom to associate with whomever they wanted. Despite having just a fourth-grade education, she worked her way up from factory jobs to clerical jobs, including eventually working as a secretary for the NKVD (the predecessor to the KGB). It is fascinating to see marriage was a matter of convenience for her and to see her divorce when her husband got too possessive. She's also certainly not shy about discussing her love affairs.

Alekseyeva writes that she never understood why she felt so close to her great-grandmother until she read the memoir and realizes that they shared the same love of adventure and risk-taking. Alekseyeva came to the U.S. with her family in the early '90s after the Chernobyl nuclear accident made living in Kiev untenable. Indeed, Alekseyeva later developed radiation-induced thyroid cancer as a teenager. As a four-year-old in Chicago who didn't speak any English, she was incredibly lonely. Especially since her mother never seemed to understand her or have a kind word for her. However, Lola embraced her immediately, and it's obvious in retrospect that she saw a lot of herself in her great-granddaughter.

Her perspective as someone enjoying a relative amount of independence who is rewarded for doing a good job reflected the national mood at the time of the 1930s. There are even moments of relative luxury. Then when Stalin's purges began in the late '30s, Lola expresses feelings of paranoia and terror that anyone could be accused of betraying the government. The narrative grows even more intense when World War II breaks out and the Germans make their big push, bombing Soviet cities relentlessly. Lola's male relatives were sent to the front right away, while she and her children barely made it out of the Ukraine alive.

Lola was a clear-headed thinker, and not one to blindly follow an ideology. That said, during WWII, there was a natural tendency for everyone to pull together and an enormous sense of pride when the Soviets reached Berlin. Still, because she was Jewish she was kicked out of one house she was renting. And her feeling of devotion was shattered when, after Stalin's death, details of his horrific abuses were detailed by the new government. "My faith collapsed. There was nothing left," she explains near the end of her narrative. That loss of faith was also a loss of the innocent idealism that was the underpinning of her experience. After all, her parents and most of her family died during the war, and what kind of country did they die for?

She stayed in the Red Army and lived in Kiev for another thirty years, but she had been shown the man behind the curtain. In much the same way, Alekseyeva grew up quickly and protested hard, her initially conservative bent long gone. That said, this is not an overtly political book; indeed, both women wind up having mixed feelings about politics. Ultimately, it's a book about how not every member of our family is necessarily someone we are going to be close to, and that being close to one's family winds up being as much a choice as choosing one's friends. The ending, which spurred the creation of the book, is a touching tribute to mutual perseverance.

The problem with the book is entirely in its visual presentation. Alekseyeva is a fine cartoonist and uses her brush to create expressive characters. Her page layouts are interesting and varied. At times, she uses a standard grid. On other pages, she uses an open-page layout where events aren't quite as rigidly constructed. For example, there's a page where Alekseyeva is fantasizing about life in college that flows into her getting an acceptance letter from Columbia. However, the book's gray wash is oppressive and dull. Furthermore, it pulls attention to some of her weaker drawings. The book screams for a color wash approach, and not necessarily a fancy one. The application of a color or two on each page would do a lot to make the pages come alive. This is a drag on the narrative as well, because this isn't a book about a cliched understanding of Soviet Russia, where everything is an oppressive gray. This is a book about a life lived vibrantly and colorfully, at a time when there was a great deal of hope. It's also a book about blood, strife, and sacrifice, and so many of its pages cry out for reds and oranges. The paper stock and relatively small print size don't do it any favors either, and pretty much every production decision winds up hurting the book in the long run.