The valley between art and audience that the comics medium traverses is far less uncanny than the one facing animation. Before the terrain was road-graded by computers at least, cartoons could carry an unnerving vibe, the forms and movements so vivid and lively but still so alien, herky-jerky or a touch too slow or both in varying degrees, possessed of a lunatic enthusiasm in their every step. The weirdest Depression-era cartoon shorts, like Grim Natwick and Fleischer Studios' "Bimbo's Initiation" (much beloved of Jim Woodring), seem animated less by human hands than some evil spirit; windows into fictional worlds that somehow live, subject to none of the rules and sanities that mercifully govern our own.

Al Columbia has built a comics career in territory as close to this uncanny valley as pictures that don't move can get. A superb draftsman, Columbia can pull on the smooth white gloves of the Fleischer house style with ease. But where actual old cartoons only hint vaguely at their evil spirit's existence, Columbia's work gets down on the floorboards and slithers along in the wake of its bloody trail, marrying a legitimately iconic American idiom to content as ghoulish and ghastly as anything comics has ever played host to. His latest book, Amnesia: The Lost Films of Francis D. Longfellow Supplementary Newsletter no. 1, spotlights a cartoonist who has identified exactly what's most powerful about his own work building himself an elaborate metafictional theater to project it in.

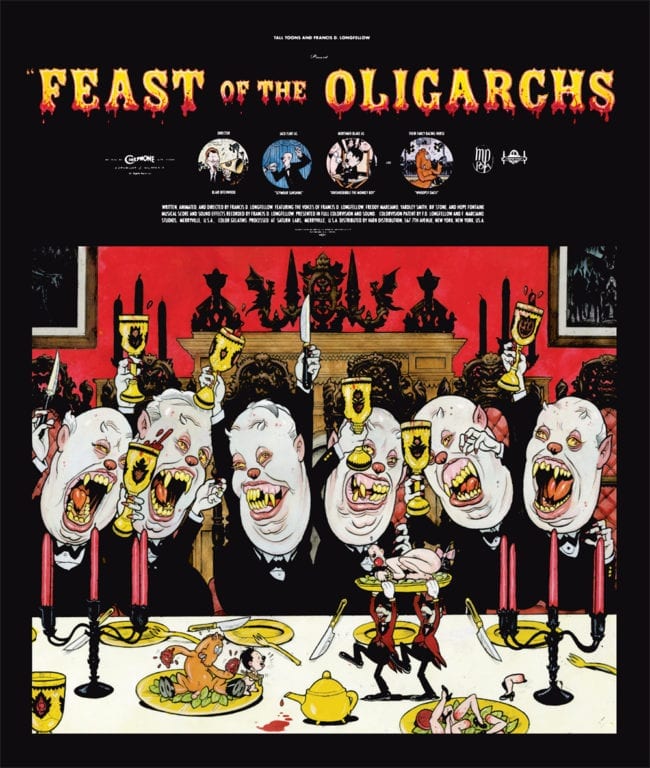

Columbia himself plays second fiddle in Amnesia. The comic purports to feature Columbia's "exacting reconstructions" of "Golden Age animator, Podsnap Studios founder, and patented inventor of the Colorvision motion picture process" Francis Longfellow's original animation cels, unearthed at the "Merryville Examiner Microfilm Library". Along with rumors of drug abuse and occultism in his personal life, Longfellow brought a heavy Fleischer influence to the table, with bambi-eyed children, clodhoppered feet, and white-gloved hands galore filling up hyperantic, detail-stuffed frames. The content, however, is downright Satanic. An obese, jovial butcher dismembers babies with a battered meat cleaver, flies dessicate the corpse of a Tweety Bird antecedent before spawning maggot larvae inside it, and "Skinless Slim" wanders through a junkyard filled with dead kittens and leering, broken dolls. Perhaps as a result of the restoration process, Longfellow's drawings bear a more than striking resemblance to Columbia's own. Horrifying at first blush, they are imbued with a wicked humor and insane level of craft that reward repeat readings.

Columbia himself plays second fiddle in Amnesia. The comic purports to feature Columbia's "exacting reconstructions" of "Golden Age animator, Podsnap Studios founder, and patented inventor of the Colorvision motion picture process" Francis Longfellow's original animation cels, unearthed at the "Merryville Examiner Microfilm Library". Along with rumors of drug abuse and occultism in his personal life, Longfellow brought a heavy Fleischer influence to the table, with bambi-eyed children, clodhoppered feet, and white-gloved hands galore filling up hyperantic, detail-stuffed frames. The content, however, is downright Satanic. An obese, jovial butcher dismembers babies with a battered meat cleaver, flies dessicate the corpse of a Tweety Bird antecedent before spawning maggot larvae inside it, and "Skinless Slim" wanders through a junkyard filled with dead kittens and leering, broken dolls. Perhaps as a result of the restoration process, Longfellow's drawings bear a more than striking resemblance to Columbia's own. Horrifying at first blush, they are imbued with a wicked humor and insane level of craft that reward repeat readings.

The conceit of Amnesia is an excellent one, and it foregrounds what may be a less obvious aspect of Columbia's talent: his understanding that horror flourishes when as little as possible is seen. His previous book, Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days - Artifacts and Bone Fragments, is a study in ellipsis as storytelling, displaying half-finished, torn, dirt-stained, and otherwise degraded drawings that comprise slivers of what may be a horrific master story of children alone in a schizophrenic nightmare world, or perhaps just an endlessly regenerating cartoon purgatory. Columbia pulls a different version of the same trick in Amnesia, providing single images as code for master narratives we are left to imagine for ourselves, and giving us an encore by spinning out bits of an equally dark yarn about the work's creator. Taken further toward completeness, Columbia's work could run the risk of feeling trite, like Emily the Strange comics amped up to Xxxtreme Levelz. Smashed to bits and left for dead in partial form, they are brutally effective horror comics.

The conceit of Amnesia is an excellent one, and it foregrounds what may be a less obvious aspect of Columbia's talent: his understanding that horror flourishes when as little as possible is seen. His previous book, Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days - Artifacts and Bone Fragments, is a study in ellipsis as storytelling, displaying half-finished, torn, dirt-stained, and otherwise degraded drawings that comprise slivers of what may be a horrific master story of children alone in a schizophrenic nightmare world, or perhaps just an endlessly regenerating cartoon purgatory. Columbia pulls a different version of the same trick in Amnesia, providing single images as code for master narratives we are left to imagine for ourselves, and giving us an encore by spinning out bits of an equally dark yarn about the work's creator. Taken further toward completeness, Columbia's work could run the risk of feeling trite, like Emily the Strange comics amped up to Xxxtreme Levelz. Smashed to bits and left for dead in partial form, they are brutally effective horror comics.

The kind of blackened, pseudohistorical Americana that Amnesia traffics in has a sizable family tree, stretching across pop culture from Tom Waits and Nick Cave through David Lynch and Guillermo del Toro to James Ellroy and Mark Danielewski. Within comics, Rick Geary and Robert Crumb have laid out their own claims to it. Columbia's work has a slightly different aura, though; a singlemindedness of purpose and a disinterest in functioning as mere entertainment. Reading Amnesia, I was most forcibly reminded of Chris Ware, whom I've always seen Columbia as a dark mirror of. It's not just that the two share certain inflections of style. Ware too engages in highly self-aware explorations of the dark side of American cartooning's history, using the tools of a particular trade to disassemble the box he found them in. But where Ware is apt to unearth the strange and ugly before tossing it aside with a nihilistic laugh, Columbia conveys a feeling of utter entrancement to his readers, holding up things long buried to glitter malevolently in the sun.

The kind of blackened, pseudohistorical Americana that Amnesia traffics in has a sizable family tree, stretching across pop culture from Tom Waits and Nick Cave through David Lynch and Guillermo del Toro to James Ellroy and Mark Danielewski. Within comics, Rick Geary and Robert Crumb have laid out their own claims to it. Columbia's work has a slightly different aura, though; a singlemindedness of purpose and a disinterest in functioning as mere entertainment. Reading Amnesia, I was most forcibly reminded of Chris Ware, whom I've always seen Columbia as a dark mirror of. It's not just that the two share certain inflections of style. Ware too engages in highly self-aware explorations of the dark side of American cartooning's history, using the tools of a particular trade to disassemble the box he found them in. But where Ware is apt to unearth the strange and ugly before tossing it aside with a nihilistic laugh, Columbia conveys a feeling of utter entrancement to his readers, holding up things long buried to glitter malevolently in the sun.

With Amnesia's Podsnap Studios, I got the feeling that Columbia has found his ACME Library of Novelty, an edifice of the mind that, once erected, begs for excavation. Future supplementary newsletters are promised in this one's indicia. Who knows what nightmares may come?

With Amnesia's Podsnap Studios, I got the feeling that Columbia has found his ACME Library of Novelty, an edifice of the mind that, once erected, begs for excavation. Future supplementary newsletters are promised in this one's indicia. Who knows what nightmares may come?