America is truly a nation of cults.

While every country has its cults, and some of them have been bigger, stranger, and more destructive than their American counterparts, no one has had more, and no one has exported them the way we do. When America does something, it does it to excess, and that includes bizarre religious sectarianism. Your Orders of the Solar Temple, your Aum Shinrikyos, and your Falun Gongs may make a big splash every now and then, but the United States dominates the world of ‘new religious movements’ the same way it dominates the Olympic Games.

American Cult, a collaborative anthology from Paper Rocket & Silver Sprocket Comics, somewhat betrays its title; it’s not really a history, as it doesn’t present any kind of unbroken through-line of American religious cults, nor does it make any attempt to explain why America seems so particularly vulnerable to this sort of thing. It even violates its own rules (spelled out in the foreword by editor Robyn Chapman); the Sullivanians, detailed in a fascinating installment by Jesse Lambert, were not religious, but a strange blend of quasi-leftist politics and psychotherapy, while Chapman’s own section on the Heaven’s Gate cult violates her rule that cults are totalitarian in nature.

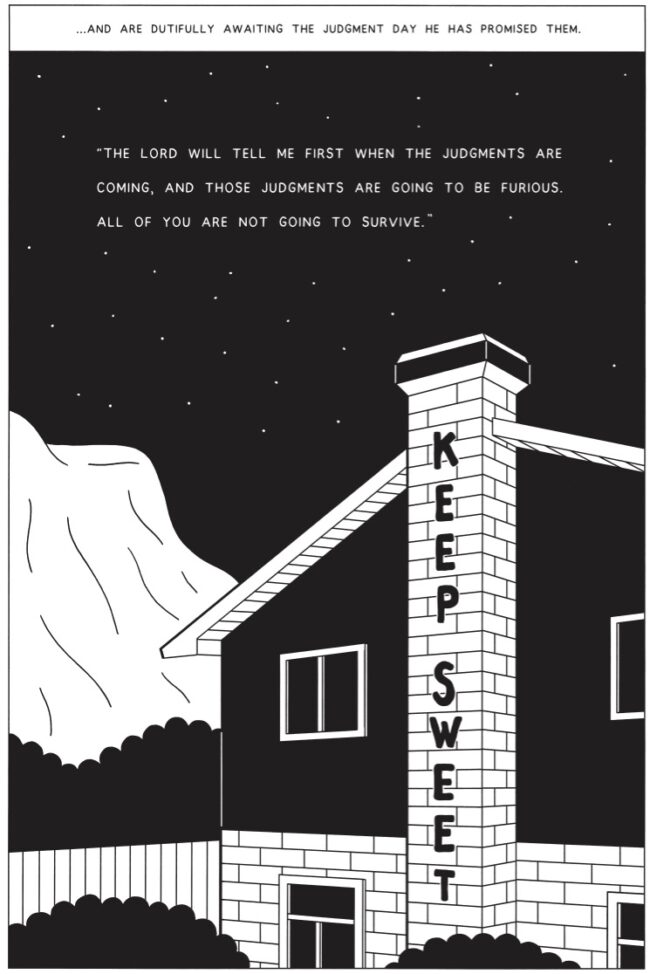

Of course, what is and isn’t a cult is always a matter of dispute, both to people inside the cult and outside of it. (Plentiful evidence of this can be seen in Lonnie Mann’s installment, simply titled “Orthodox Judaism is a Cult”; Robert Sergel’s chapter on Mormon cultist Warren Jeffs takes pains, meanwhile, to argue that mainstream Mormonism is no more or less a cult than any other major religion.) This definitional ambiguity may be the only consistent factor in a book that is simultaneously very compelling and wildly inconsistent in tone.

Part of this is attributable to the background of the diverse set of creators. Some have backgrounds in the very cults they write about, while others approach the subject from an outsider’s perspective, making for a mood so variable as to be disorienting. Like all anthologies, American Cult lives and dies by the storytelling ability of its creators, so it’s probably unfair to judge it as a kind of nonfiction collection built around a specific subject and envision it more as an impressionistic art project with a loose central theme.

This becomes apparent from the very first installments. The book begins with the vague but fascinating tale of “The Monk in the Cave”, where Steve Teare details the life of arguably America’s first cult leader, Johann Kelp, a Transylvanian devotee of the mystic Jakob Boehme. This is followed by “Inside Oneida” (a look at one of the many religious cults of the ‘burned-over district’ of western New York during the Second Great Awakening; its erotic art and poetic narration by Emi Gennis makes it one of the best chapters in the collection) and Ellen Lindner’s look at the Fruitlands commune, one of the first cults to ensnare a celebrity in the form of author Louisa May Alcott. But the book then immediately jumps to California in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, skipping over almost a century of American history, which was in no way lacking in bizarre religious sectarianism.

Still, for casual observers and dedicated fans of American cults, the latter half of the 20th century is where the action was, so it’s easy enough to forgive the lapse. Rosa Colón Guerra’s chapter on David Berg and the Family International, who pioneered “flirty fishing” – essentially, luring in male followers with honeypot tactics – is terrific; Janet Harvey and Jim Rugg’s section on the Manson Family covers pretty familiar ground, but its presentation, somewhat recollecting a Chick tract, is oddly interesting. Andrew Greenstone’s chapter on the woozy Source Family has an appropriately shaggy psychedelic quality, while Lara Antal’s “Mindbending”, on the sinister Process Church of the Final Judgement, is scary enough by implication if you already know about that group’s dark activities, but if you don’t, it might come across as overly impressionistic or simply confusing.

A lot of the kick of a book like American Cult comes from learning all the bizarre details for the first time. For those unfamiliar with most of the stories told here, it’s likely to be a cornucopia of riches: the whirling blend of violence, sexual misconduct, and theft that never seems to ring alarm bells among true believers; the odd tendency of cults have to ensnare the rich, the famous, and the powerful; the curious details and the things left unsaid. But even for veteran cult-watchers, there are plenty of surprising revelations. I learned from Josh Kramer and Mike Dawson’s “Cults Reoriented” chapter that Meher Baba’s organization in America was largely funded by the CEO of the Cheesecake Factory. Ben Passmore’s chapter on Philadelphia’s MOVE shatters plenty of long-standing myths about the group: they weren’t nationalists, they weren’t exclusively black, and their lack of political coherence was more of a problem than their possession of it. Ryan Carey and Mike Freiheit’s history of Jonestown devolves a bit too much into conspiratorial speculation, but it’s understandable given the light it sheds on Jim Jones’ history with a notorious CIA torturer; it’s also a haunting and well-drawn piece that stands out as one of the best selections in the anthology, more than making up for its flaws.

There’s plenty more here: Lisa Rosalie Eisenberg’s “Playing the Game” is a roller-coaster look at Chuck Dederich, the tragicomic founder of Synanon; J.T. Yost presents an unnerving insider’s perspective on the notorious Westboro Baptist Church; and the final installment, Box Brown’s look at the NXIVM multi-level marketing scam/sex cult, is a satisfying conclusion to the book. The art and the writing bounce from pole to pole in terms of quality, and American Cult never quite coheres into the consistency of a true nonfiction treatment of new American religious movements. But taken for what it is, it’s a pretty good reflection of its subject matter: never coherent, often shocking, full of little revelations, and liable to pull you in to its strangely riveting view of the world.