I might as well try to round up some of my recent reading material.

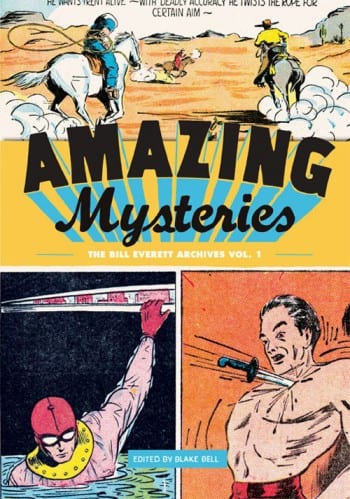

I've been irked and then irked at my irksomeness, then irked again by, of all things, Amazing Mysteries: The Bill Everett Archives Vol 1, edited by Blake Bell (Fantagraphics). It seems so pointless to be irked by this kind of book, which is published for a specialist audience and really broadcasts no greater ambitions than it demonstrates. But nevertheless, the problem with the current fucking onslaught of historical/archival projects is that very few of them make any effort to justify their own existence. By gathering together this work and its corresponding bare facts, the editor is making a claim for its importance, but it's a claim that, in the case of most 1930s and '40s comic books, really does need buttressing in the form of a prose argument. Without that component we're just left with a pile of books, which is great as raw material, but there's little critical or even historical dialogue around the stuff, and so little incentive to create any, that we wind up back at zero. The Everett book includes a selection (though the rationale behind the selection is not explained -- it's neither termed "the best" nor "all we could find" nor "the grooviest". Etc.) of superhero stories created by Everett from 1938 to 1942 organized by feature. It includes ongoing titles like "Amazing-Man" and "Hydro-Man" and briefer ones including "Dirk the Demon" ("24th Century Archeologist"!) and "The Conquerer". A particular favorite of mine is Sub-Zero Man, who has ice-powers and is nearly scalped by a nude professor. All of these stories show the beginnings of Everett's signature swooping line and vivid, erotic imagination. They are also unusually violent in places, exhibiting Everett's signature taste for the bizarre -- men bite snakes; hooded characters (ah for a whole essay on the hooded villains of the 1940s) proliferate; limbs dissipate and reappear; etc.

I've been irked and then irked at my irksomeness, then irked again by, of all things, Amazing Mysteries: The Bill Everett Archives Vol 1, edited by Blake Bell (Fantagraphics). It seems so pointless to be irked by this kind of book, which is published for a specialist audience and really broadcasts no greater ambitions than it demonstrates. But nevertheless, the problem with the current fucking onslaught of historical/archival projects is that very few of them make any effort to justify their own existence. By gathering together this work and its corresponding bare facts, the editor is making a claim for its importance, but it's a claim that, in the case of most 1930s and '40s comic books, really does need buttressing in the form of a prose argument. Without that component we're just left with a pile of books, which is great as raw material, but there's little critical or even historical dialogue around the stuff, and so little incentive to create any, that we wind up back at zero. The Everett book includes a selection (though the rationale behind the selection is not explained -- it's neither termed "the best" nor "all we could find" nor "the grooviest". Etc.) of superhero stories created by Everett from 1938 to 1942 organized by feature. It includes ongoing titles like "Amazing-Man" and "Hydro-Man" and briefer ones including "Dirk the Demon" ("24th Century Archeologist"!) and "The Conquerer". A particular favorite of mine is Sub-Zero Man, who has ice-powers and is nearly scalped by a nude professor. All of these stories show the beginnings of Everett's signature swooping line and vivid, erotic imagination. They are also unusually violent in places, exhibiting Everett's signature taste for the bizarre -- men bite snakes; hooded characters (ah for a whole essay on the hooded villains of the 1940s) proliferate; limbs dissipate and reappear; etc.

Bell provides copious dates and raw data, as well as a solid understanding of Everett's career, but he doesn't go beyond that into any kind of analysis or broader context. His introductions to each feature mostly recite the origin story and never explain why these stories, as opposed to others, were chosen. Only once, in his intro to the "Amazing-Man" section, does Bell qualify the art, and then only with the same quote from Gil Kane used in Fire and Water (I can't tell if the present book is meant to rely on Fire and Water or, as a series, supplant it). This book contains stories that, for the most part, are primarily of interest to those of us wanting to understand Everett as an artist and human, but Bell can't connect the material to the man and his time beyond dates and places. His greatest contextual leap is just bizarre: Twice (once in his biography, Fire and Water, and once here) qualifying Everett by noting this his creation of The Sub-Mariner presages that of the character Wolverine, as though that somehow matters to Everett himself. And yet Bell doesn't explain anything about the evolution of Everett's work and its relationship to contemporaneous visual culture. Between 1938 and 1941 the drawing leaps forward. Why? How? Is it related to Virgil Finlay, perhaps? To Alex Raymond? Similarly, in his intro Bell recites the tired Topffer-to-newsstand comic book history but doesn't seem interested in what Everett's place was amongst his peers. Was his work better? Worse? And when Bell reels off a list of Everett's self-mythologizing tales he simply surmises that Everett liked a good story (yes, like a musician likes a good tune), offering no ideas about why Everett might've spun these tales. Surely there's something to be found in his lineage, in his general approach to art, or perhaps his relation to fandom. Now, the reason I get annoyed at my own response is that Bell's choices are, to a degree, a matter of taste, and he's certainly done the hard work of digging up this information, for which he's to be commended. It's very difficult to achieve chronological clarity in murky comic book history. But I want the dates and the analysis and ideas about the work. Bell may just want the dates. That's fine as far as it goes, but to me it feels limited.

And those limitations are highlighted by things like a page dedicated to a gleeful comparison between the original and the printed versions of a 1971 Marvel comic book panel by Everett and Gene Colan that features The Black Widow's pronounced nipples. A full page in a book published in 2012. And a book about work from the late 1930s and early '40s. It's so adolescent and piggish that it somewhat undercuts the seriousness of Bell's own work. It also inadvertently underscores the unspoken missing piece of the entire book (and presumably the series): Everett's work at Timely/Marvel. Despite numerous mentions in Bell's text of Everett's work at Timely/Marvel as being more or less primary to his career, there's no explanation for why there is none of that work included in the book. I'm sure there were rights issues, but maybe a nod in that direction would be a good idea.

Anyhow, I'm fascinated by Everett, who was clearly possessed of an active and conflicted interior life and created some of the most impassioned and beautiful comic book art of all time, and so the stories herein are of interest to me, but they also deserve a more imaginative text and a clarity of purpose that is missing from Amazing Mysteries.

Speaking of in-depth, I have been enjoying The Art Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist (Abrams ComicArts). Aside from an excellent interview by Kristine McKenna and great essays by Ken Parille and Chris Ware, it's a real pleasure (yes, a pleasure, as in, enjoyable and satiating) to be able to take in this much artwork by Clowes in one sitting. Y'know, Clowes is such an immersive storyteller that I sometimes lose track of the art-as-art. This is a virtue in his cartooning, but it's nice to be forced to slow down and just look. So, there's plenty of original art, which is particularly rewarding for such an intense, line-focused draftsman (a subject Ware writes about very well) as well as record covers, roughs, and New Yorker covers. What has stuck with me the most, though, is a compelling section of portraiture with an excellent accompanying essay by curator Susan Miller. Miller makes a winning case for these drawings as a body of work, and then nicely positions it with the rest of the artist's sensibility; also, it's a thrill to see so many Clowes faces gathered in one place staring out at you.

Speaking of in-depth, I have been enjoying The Art Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist (Abrams ComicArts). Aside from an excellent interview by Kristine McKenna and great essays by Ken Parille and Chris Ware, it's a real pleasure (yes, a pleasure, as in, enjoyable and satiating) to be able to take in this much artwork by Clowes in one sitting. Y'know, Clowes is such an immersive storyteller that I sometimes lose track of the art-as-art. This is a virtue in his cartooning, but it's nice to be forced to slow down and just look. So, there's plenty of original art, which is particularly rewarding for such an intense, line-focused draftsman (a subject Ware writes about very well) as well as record covers, roughs, and New Yorker covers. What has stuck with me the most, though, is a compelling section of portraiture with an excellent accompanying essay by curator Susan Miller. Miller makes a winning case for these drawings as a body of work, and then nicely positions it with the rest of the artist's sensibility; also, it's a thrill to see so many Clowes faces gathered in one place staring out at you.

Also on the desk: Paul Kirchner's The Bus (Tanibis Editions), which collects the titular comic strip. Like a lot of work that initially appeared in Heavy Metal, Kirchner's strip has been kinda lost in the intervening generation, but I was happy to discover it for myself. It's a simple conceit -- man waits for bus; surreal hi-jinx ensue. Kirchner's enjoyed a mini-renaissance of late, with his equally tight and inventive "Dope Rider" strip now online in full. Kirchner was a Wally Wood assistant -- his drawings have that Wood stillness that I love so much, but with a modest warmth, too. Recommended, and not just because I started selling it a couple weeks after I wrote this piece.

Books by Ettore Sottsass (Corraini). This is comics-related, natch. Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass was a prodigious book-maker. In the 1960s his work, like so many other groovy visual hybrid Europeans, incorporated lots of comic book art and psychedelic imagery. But most pertinently to TCJ, the design movement he spearheaded, Memphis (1981-1987), was built on forms abstracted from a kind of idealized cartoon language. Sotsass managed to conceive and manufacture fairly outlandish objects, all of which were based in thinking through drawing. Anyhow, the book at hand catalogs not only all of his many books but also magazine inserts, brochures and even the odd business card by Sotsass. It's a good overview of his long career and a demonstration of his restless intellect.

Books by Ettore Sottsass (Corraini). This is comics-related, natch. Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass was a prodigious book-maker. In the 1960s his work, like so many other groovy visual hybrid Europeans, incorporated lots of comic book art and psychedelic imagery. But most pertinently to TCJ, the design movement he spearheaded, Memphis (1981-1987), was built on forms abstracted from a kind of idealized cartoon language. Sotsass managed to conceive and manufacture fairly outlandish objects, all of which were based in thinking through drawing. Anyhow, the book at hand catalogs not only all of his many books but also magazine inserts, brochures and even the odd business card by Sotsass. It's a good overview of his long career and a demonstration of his restless intellect.

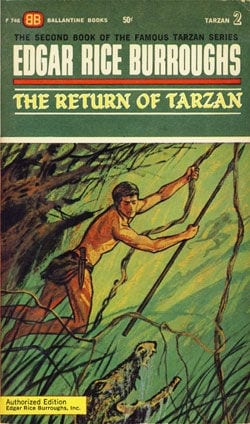

The Return of Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs. I hadn't read any ERB until just this past summer and while he can be a little tedious, I have to say: I get it, and I can really wile away an evening reading him. The entire superhero comic template is right here in these novels that emphasize nobility, strength, racial superiority and manliness. Amazing as documents and as a kind of machine that produces precisely the feelings you're meant to have when experiencing "adventure".

The Return of Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs. I hadn't read any ERB until just this past summer and while he can be a little tedious, I have to say: I get it, and I can really wile away an evening reading him. The entire superhero comic template is right here in these novels that emphasize nobility, strength, racial superiority and manliness. Amazing as documents and as a kind of machine that produces precisely the feelings you're meant to have when experiencing "adventure".

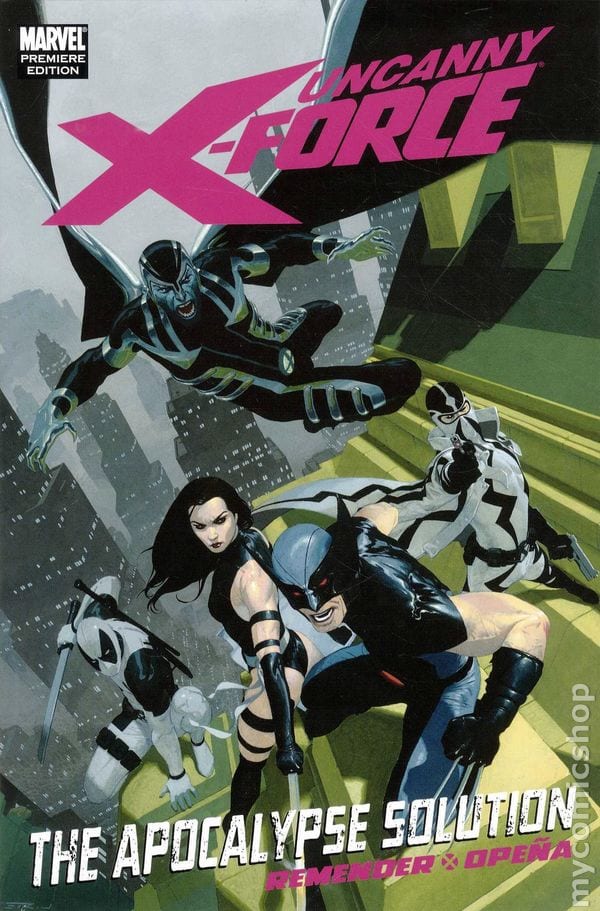

The Uncanny X-Force by Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña (Marvel). Tucker Stone and Brian Chippendale recommended this one. It's basically a Heavy Metal comic book starring some X-Men I sort of remember, including the aforementioned Wolverine, heir to Bill Everett's talent. There's not much continuity to worry about and Remender and Opena work hard to create a space in which to choreographic extended and very graceful action sequences.

The Uncanny X-Force by Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña (Marvel). Tucker Stone and Brian Chippendale recommended this one. It's basically a Heavy Metal comic book starring some X-Men I sort of remember, including the aforementioned Wolverine, heir to Bill Everett's talent. There's not much continuity to worry about and Remender and Opena work hard to create a space in which to choreographic extended and very graceful action sequences.

It's really finely rendered along the lines of Moebius and Barry Windsor-Smith, and yet also composed sort of like a video game, as the group encounters various obstacles, makes choices, and step through sequences that seem self-consciously pre-determined. There's nothing profound here, and the art really carries it, but this is fine world-building SF work that seems only incidentally related to the X-Men franchise.

It's really finely rendered along the lines of Moebius and Barry Windsor-Smith, and yet also composed sort of like a video game, as the group encounters various obstacles, makes choices, and step through sequences that seem self-consciously pre-determined. There's nothing profound here, and the art really carries it, but this is fine world-building SF work that seems only incidentally related to the X-Men franchise.

Finally, Erro is one of those artists you see little bits of in books on pop art and sometimes in comic art histories. He's Icelandic and never had much of a following in the U.S., despite a successful career in Europe. Anyhow, Portrait and Landscape (Hatje Cantz) is the only monograph in recent memory that covers his 1950s-1970s work, some of which was shown 6 or 7 years ago at The Grey Art Gallery at NYU, but otherwise has remained elusive. For years Erro's paintings are massive, overstuffed compositions that begin as collages and maintain that overlapping, disjointed feel. Each "landscape" painting has a pronounced subject juxtaposed with a fresh horizon. "Carscape" (1969) imagines cars collages to a distance blue sky; "Fishscape" (1974) has Sgt. Fury (in triplicate) descending on a mass of fish. And so on. Later paintings explicitly examine comic languages, like "French Comicscape" (all the Franco-Belgium icons) and "Darkdreamscape" (horrific drawn moments). Anyhow, this new book is oversized and beautifully printed, with a couple of good essays and a well filled-out chronology. It's something of a relief to have this handy.

Finally, Erro is one of those artists you see little bits of in books on pop art and sometimes in comic art histories. He's Icelandic and never had much of a following in the U.S., despite a successful career in Europe. Anyhow, Portrait and Landscape (Hatje Cantz) is the only monograph in recent memory that covers his 1950s-1970s work, some of which was shown 6 or 7 years ago at The Grey Art Gallery at NYU, but otherwise has remained elusive. For years Erro's paintings are massive, overstuffed compositions that begin as collages and maintain that overlapping, disjointed feel. Each "landscape" painting has a pronounced subject juxtaposed with a fresh horizon. "Carscape" (1969) imagines cars collages to a distance blue sky; "Fishscape" (1974) has Sgt. Fury (in triplicate) descending on a mass of fish. And so on. Later paintings explicitly examine comic languages, like "French Comicscape" (all the Franco-Belgium icons) and "Darkdreamscape" (horrific drawn moments). Anyhow, this new book is oversized and beautifully printed, with a couple of good essays and a well filled-out chronology. It's something of a relief to have this handy.

[Since writing this like 3 weeks ago and then letting it sit, the Wally Wood Artist's Edition arrived. It is amazing on a bunch of levels and I'll cover it in full in a future post. I know, I know: You can hardly wait!]