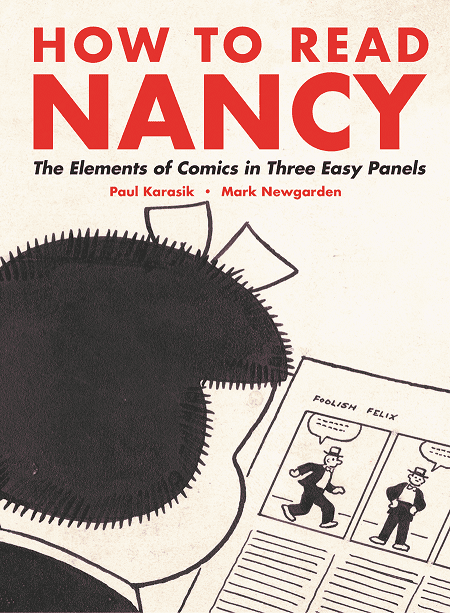

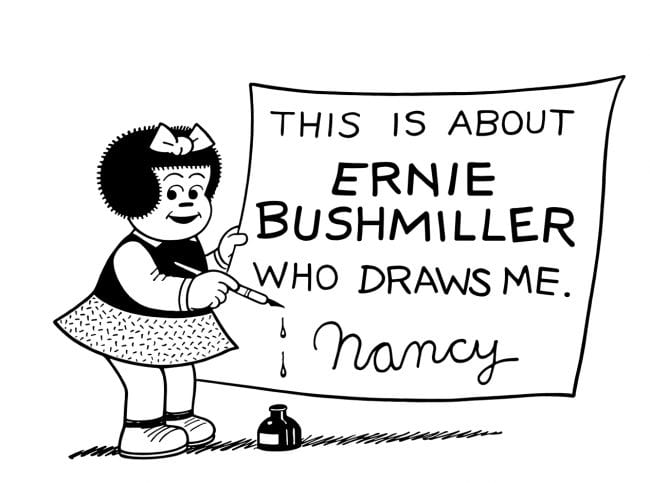

How to Read Nancy is the best book ever written about comics. No question. Besides using a single 1959 Nancy strip to demonstrate all of the formal properties of the medium in an unprecedented fashion, Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden manage to take that same comic and map a huge artistic / professional /industrial/ historical story about comics. This story includes: How a gag might have a history unto itself; how a teenage apprentice could become a giant of the medium; how the damn comics were actually printed; how arbitrarily they could be published; and casual-seeming dives into cartoonists-gone-Hollywood, particular studio building, and even a now-obscure New York paper. I don’t think there’s another book that covers all of those facets, all of which are integral to the comics of the 20th century and few of which have been told. And Karasik and Newgarden do it with concision and, of course, wit. It’s truly inspired. On a personal note, Paul Karasik was the first cartoonist I interviewed for publication (Ganzfeld 1) and Mark Newgarden maybe the first cartoonist I visited in New York. I interviewed them by email, and they answered in a single voice. Please visit the book's website for more info and a list of upcoming events.

How to Read Nancy is the best book ever written about comics. No question. Besides using a single 1959 Nancy strip to demonstrate all of the formal properties of the medium in an unprecedented fashion, Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden manage to take that same comic and map a huge artistic / professional /industrial/ historical story about comics. This story includes: How a gag might have a history unto itself; how a teenage apprentice could become a giant of the medium; how the damn comics were actually printed; how arbitrarily they could be published; and casual-seeming dives into cartoonists-gone-Hollywood, particular studio building, and even a now-obscure New York paper. I don’t think there’s another book that covers all of those facets, all of which are integral to the comics of the 20th century and few of which have been told. And Karasik and Newgarden do it with concision and, of course, wit. It’s truly inspired. On a personal note, Paul Karasik was the first cartoonist I interviewed for publication (Ganzfeld 1) and Mark Newgarden maybe the first cartoonist I visited in New York. I interviewed them by email, and they answered in a single voice. Please visit the book's website for more info and a list of upcoming events.

You guys are nuts!

Yes.

You both have spent decades worshipping this strip. Are you done with Nancy now? Have you exhausted it for yourselves?

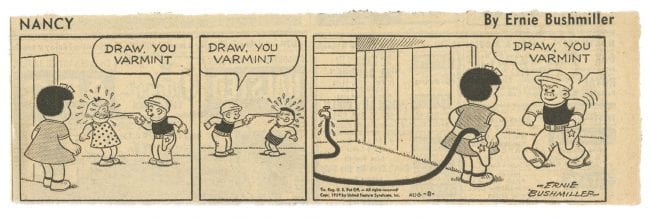

Well, we honestly thought our little side project would take a year or two to dispatch. We thought we knew the August 8, 1959 episode pretty well. Our original 1988 essay, which appeared in Brian Walker’s The Best of Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy, contained eight levels of deconstruction and after teaching it all these years we figured there might be a handful more we could squeeze out. Ten years later How to Read Nancy has just landed —with a grand total of forty-three discrete aspects of this damned that strip we have isolated and analyzed (plus a comprehensive biography, seventeen appendices, dozens of meticulously restored line art strips –but wait! There’s more!). Yet, despite the myriad grueling efforts it has taken to produce this book (Dun’t Esk!), we continue to be mesmerized by Nancy.

We still see fresh Bushmiller strips that we have never seen before and still find them amusing, impressive, occasionally jaw-dropping… and, yes, fresh.

We still use Nancy in the classroom (as we hope many comics curriculum instructors will do once they get a hold of the book) and find that our students, as often as not, become equally enchanted.

So, while we can barely stand to look too closely at the finished book yet (still afraid the new baby has an extra thumb) we will always adore Nancy.

You mention a few times that Nancy has not received the historical attention (or affection) it deserves. I wonder if that’s because is so prosaic on the surface. What is it about the way comic-strip history has been written that you think kept out Nancy? Is part of your contention that the almighty gag is equal to, say, the emotional heft of Krazy Kat or Peanuts, or the grandeur of Little Nemo? I think the answer is yes, and I agree, but perhaps you can explain a bit.

Krazy Kat and Little Nemo resemble “Art.” Peanuts resembles “Philosophy.” Nancy resembles nothing more and nothing less than a comic strip (and a gag-driven, self-proclaimed “dumb” one at that), hence: easily dismissed from the canon.

The public’s affection has always been there. Savvy critics such as Manny Farber certainly “got” Nancy at the time of its initial popularity, but the next wave (1960s–1990s) of “serious” comics historians tended to revile the strip, for a variety of reasons that reveal more about their agenda (and their generational bias), than the merits of the work. Nancy was simply a hard sell for anybody trying to get the middlebrow public to take comics “seriously” when, for whatever reason, that was the name of the game. This includes the heroic Bill Blackbeard who single-handedly archived complete runs of nearly every 20th century American comic strip of consequence except Nancy, so deep was his ambivalence. (Due to this sin of omission, as far as we know, there is no complete hardcopy run of this once–ubiquitous comic strip left on planet earth.)

Our choice of the late, great Jerry Lewis for a foreword was highly intentional, yet despite some obvious parallels, Ernie Bushmiller never had the contemporary equivalent of the French New Wave publicly championing his work. Lewis gave us a great compliment in saying that ours is “a book that was written with an infinite care rarely seen in today's world.” This is how we feel about Nancy.

We hope that How To Read Nancy will encourage the skeptics (who assume that Nancy was just another vapid kiddie strip), as well as the hipsters (who Instagram their Sluggo tattoos, yet have never actually read it), to reevaluate and appreciate the mastery of Bushmiller’s work.

Is there any evidence that Bushmiller worked on any projects other than Nancy once he found success? Spin-off strips? New ideas for strips? Sunday painting?

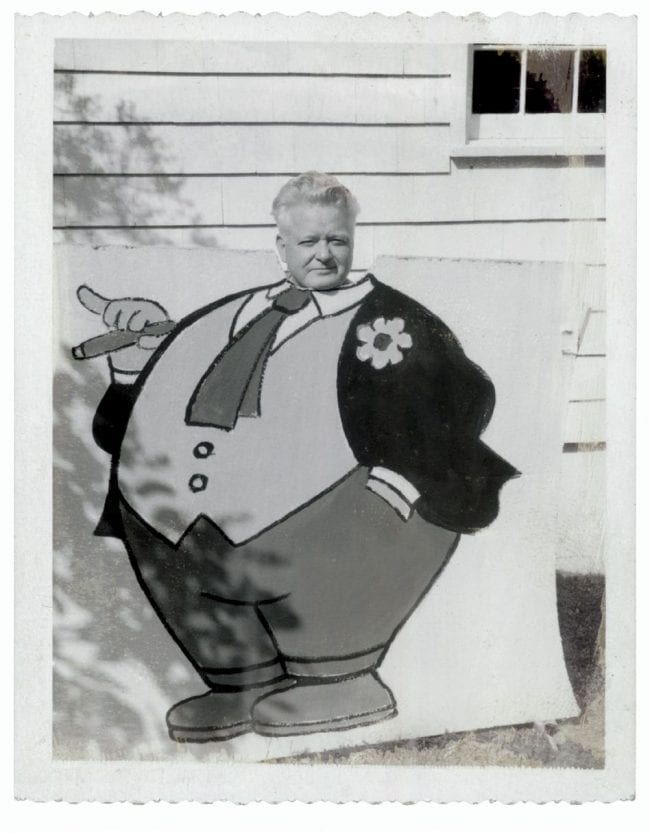

Ernie Bushmiller wanted to be a cartoonist from the get-go and got his big break moving up the food chain from office boy to art assistant to cartoonist before the age of 20. Once stationed in that command post, his dream was fulfilled and he never felt the need to expand, but rather to focus on being the best cartoonist he could be. “Focus” might be an understatement, however. Bushmiller the artist, we came to learn, was a completely driven individual.

The story goes that Ernie labored deep into the night with numerous drawing boards set up around his studio, working on different strips simultaneously, in various states of completion. His goal was to render a week’s worth of Nancy within a half-week, so that he could nominally relax with his wife and pets, putt some golf balls around the iconic multi-rock formation outside his studio and enjoy a couple of Heinekens (all the while compulsively making notes, plans and sketches for his next round of gags.) “I know he was wrapped up in that strip,” Al Plastino put it to us. “It was his whole life. His whole life."

What was the relationship, if any, to the Mort Walker factory crew of the 1960s and '70s? Did Bushmiller maintain a generational distance?

In the mid-20th century, if you were a cartoonist based in New York who hit it big, you moved to Connecticut. Bushmiller, who settled in Stamford in 1950, was one of the leaders of the charge. (He was reportedly persuaded to make the move by Alex Raymond, who apparently believed that the New York metropolitan area was destined for an imminent nuclear attack by the USSR.)

By the time Mort Walker and his crowd arrived, Bushmiller was well ensconced. We presume that there was a cordial professional respect, but Bushmiller was part of another generation, a survivor of the Jazz Age who had little in common with this younger, “hipper” post-war comic-strip-factory crowd. According to Al Plastino (speaking of Bushmiller in the 1970s): “He wasn’t social… He wanted to be left alone. That’s all. That was his privilege… He didn’t want NOBODY there to share his life… This is how reclusive he was: I wanted to visit him and let him know it. Ernie told me the next time he would see him he’d be in a casket.”

The appendices are masterful and could be expanded into a book of their own. Were other appendices considered?

considered?

We settled on seventeen appendices in all and truth be told, probably could have gone on to 170.

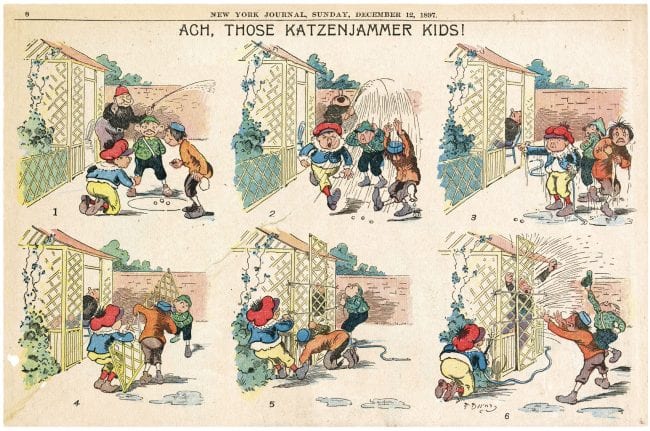

Of all the appendices, Appendix 6: “The Hose Gag” is the one that demanded the deepest excavation. Because this book is about the examination of the Object itself, we were determined to reproduce only primary source materials (and did, in 99% of all cases). Tracing the lineage of the Hose Gag, locating physical copies of ancient, obscure foreign-language humor magazines and then making arrangements for high-resolution scans, with the help of a dedicated international league of comics scholars, libraries and historical societies probably added several months (?) years (?!?) to the creation of How To Read Nancy.

While we suspect that there are more pre-1900 hose gags yet to be exhumed (post-1900 Hose Gags could easily be the subject of a master’s thesis at Bellevue), we feel that we did a reasonably thorough job (standing on the shoulders of giants, and a hearty handclasp to some first-rate, expert assistance).

That said, almost all of the other appendices could be expanded and we would gladly welcome any verifiable, academically annotated contributions to the following questions:

Appendix 1: “INSPIRATION”: Exactly what year did the toy cowboy pistol make its first appearance in the Sears Roebuck catalog?

Appendix 5: “ENTER SLUGGO”: How (and why) did Sluggo evolve sociologically, visually and linguistically over the years?

Appendix 7: “ARCHITECTURE”: After inputting all existing data in a CAD–like program, is it possible to gauge how many separate residences Nancy and Aunt Fritzi apparently inhabited over the years and generate precise floor plans for each?

Appendix 9: “AUNT FRITZI’S OTHER RELATIVES”: Can one create an accurate family tree for the Ritz family based on information culled from the entire output of Bushmiller’s strips? (And more to the point: what is Nancy’s last name?)

Appendix 10: “LUNCHEON OF THE BOATING PARTY”: What cartoonist first used a dotted line to denote concerted gaze and when? (Conclusively.)

Appendix 14: “ASSISTANTS”: We know general tasks that certain uncredited individuals performed in general eras, but exact details remain sketchy. Where are the letters, account ledgers, and illustrated personal diaries of Jerry DeMott or Will Johnson?

Appendix 15: “BEN DAY”: Did he personally render every single dot himself?

Appendix 17: “HOW TO – HOW NOT TO”: The topic of “dysfunctional comics” could easily be grist for a follow-up book unto itself. But it’s far easier to just go to your local comics shop or graphic novel section and scan the racks for this week’s releases.

What is the best non-Bushmiller story that Al Plastino told you?

A really good question.

Plastino was one of the most respected and dependable ghost artists in the business. He largely made a living out of being able to copy the styles of other artists including Bushmiller, Ham Fisher, Raeburn Van Buren, et al. Among those who have favorites in such things, his renderings of Superboy for DC Comics are often cited as exemplary. He drew the first versions of Brainiac and Kryptonite. He worked on Nancy beginning in the 1970s, when Bushmiller’s age was taking its toll and his line had become less steady. There are still many strips from this era that Bushmiller rendered himself that we feel he would have never accepted from Plastino (or Will Johnson, another cartoonist that assisted him on the strip).

Interviewing Al Plastino (several times) was one of the absolute pleasures in creating this book. He was chatty, funny, and sharp. Mostly we talked about Bushmiller, but he spoke a bit about the time that United Feature Syndicate hired him to ghost Peanuts. Plastino recalled that it was when Schulz was slated for heart bypass surgery, but others believe that it was during Schulz’s touchy contractual re-negotiation with the syndicate. In either case, Plastino was called in to hedge their bets.

Al proudly shared his taboo-shattering Peanuts approach with us: “I made Snoopy a vegetarian… and I showed the inside of his doghouse. I really liked it.” He told us he retained proofs of all these strips, nearly a full year’s worth.

“They never used any of it,” he continued, “Turned out that Schulz was six months ahead. I am certain that he did his later shaky art PURPOSELY, so nobody could replace him on the strip… I know the type of guy he was.”

I knew this book took a good deal of time. What were some of the obstacles you encountered in completing How to Read Nancy?

I knew this book took a good deal of time. What were some of the obstacles you encountered in completing How to Read Nancy?

The making of this book could literally be a book unto itself. Researching the solid nuts and bolts on thirty-seven topics on a sliding scale of obscurity, including the details of a reclusive artist’s life, became all-consuming. It would have been impossible in pre-internet days, and we were very lucky to be aided and abetted by James Carlsson, who knew the Bushmillers well and worked for Ernie in his later years.

Finding the right images could be challenging. We were very selective about what images the book absolutely needed, and what could be considered expendable. Once located, some of the most obscure items took only one email sent first thing in the morning to land a high-res scan of the original printed object in our inbox by the end of the day: perfect, headache-free, and worth their weight in gold. Others, however, were a little more complicated.

Case in point: a 2” x 3” piece of cardboard that we had to have.

It began when we met with some members of the Abby (Bohnet) Bushmiller clan for lunch. They shared recollections of Ernie, and one of the relatives (too young to have ever met the cartoonist) pulled out a cell phone to show us some shots of a few personal effects that he had inherited. Then we saw gold: Ernie Bushmiller’s 1928 press card, complete with mug shot, boldly stamped CARTOONIST” in red ink, and embossed with the New York World logo. We instantly knew WHAT we needed it for and WHERE we needed it. Our manuscript literally cried out for this image: “Minimalist? Formalist? Structuralist?” … (page turn) “CARTOONIST!”

Unfortunately, this relative also saw gold. He wasn’t interested in sharing this image with us. On this single subject over two dozen emails were traded over the course of six months. The young man finally laid HIS card on the table: He was only willing to trade us the press card for ten Morgan Silver Dollars, or two Five-Dollar Gold Indian Heads (rare U.S. coins easily totaling $1,289.47 or more at the time, retail, depending on condition).

We tried to get him to understand that all we needed was a decent scan of the press card. We tried to explain that Ernie Bushmiller’s 1928 New York World press card was of virtually no value to anyone on earth except us. We tried to explain that we did not possess ten Morgan Silver Dollars, nor two Five-Dollar Gold Indian Heads, knew of no one who did—nor had that sort of “petty cash” fund to invest in such things, if we did. We tried to explain that our publisher would laugh at such a request. We even went so far as to scare up a sympathetic, well-heeled Nancy collector (a mensch if there ever was one) willing to cough up $600 to help us out.

Nope, nope, nope, nope and nope. It was ten Morgan Silver Dollars, or two Five-Dollar Gold Indian Heads, or nothing.

So dear readers, please indulge us, and on page 26 of How to Read Nancy, try to imagine Ernie Bushmiller’s 1928 press card, boldly stamped “CARTOONIST.” It will make our book $1,289.47 better.

What was the biggest surprise in your research?

How completely and utterly intentional Ernie Bushmiller truly was about every last aspect of his work. We understood that he was an exemplary craftsman, and Nancy was a unique strip, but it turns that we really did we choose the absolute ideal 20th-century cartoonist to dissect to this sub-molecular level.

Like many of the most serious and influential graphic designers, typographers and fine artists of his era, Ernie Bushmiller was articulate, self-reflexive, and at times overtly theoretical about how his chosen medium functioned best.

Breaking down the elements of this randomly-selected strip demanded some blood, sweat, and tears on our parts, but in the end we both felt like we took a crazy, once-in-a-lifetime road trip together, through the brain of a true comics genius and back out again. We’re glad we did it — and we sincerely hope nobody else has to do anything remotely like it ever again!