Ronin occupies a strange niche within the Frank Miller oeuvre. After his massive success on Daredevil, Jenette Kahn (DC’s publisher) made him an offer he couldn’t refuse – full artistic freedom. Not just in terms of story subject but also in terms of production: publication format, printing, paper stock... the works. For a man not yet in his 30’s to be given such freedom, especially in the context of the notoriously tyrannical mainstream American market, was probably intoxicating. The result was a six-issue series, 1983-84, each issue double-sized on high quality paper. There were no commercials. Miller even controlled publication deadlines (once every six weeks). This wasn’t product, this was art. It also ended up being probably the most personally revealing thing in his career.

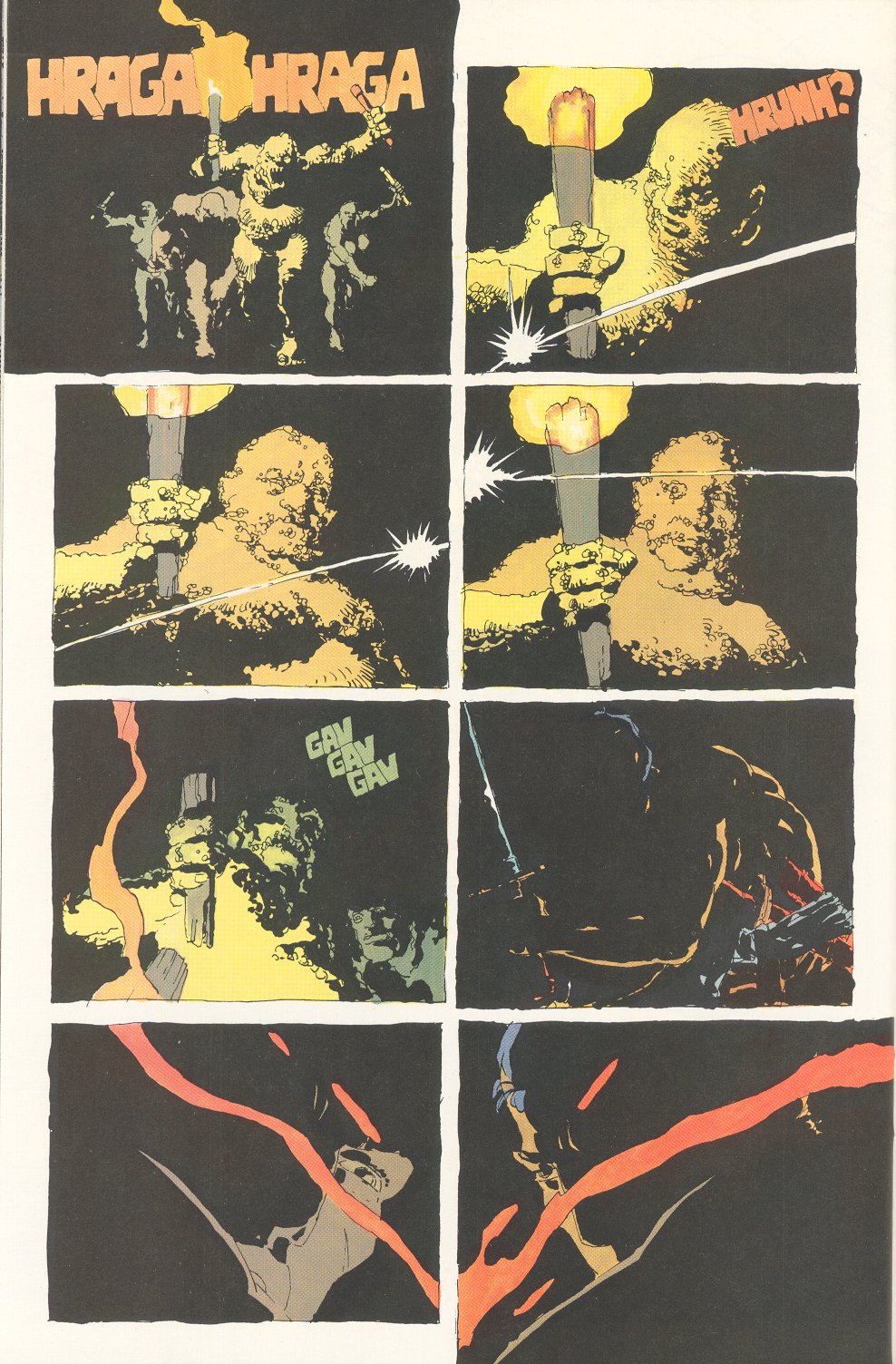

In terms of looks alone, Ronin remains a triumph. Miller was so far ahead of the curve that most artists working today are still playing catch-up. Yes, he was a shameless borrower, from Gōseki Kojima, Moebius, José Muñoz, and everyone else who caught his fancy. All these artists exist within Ronin; the end result, however, is something fresh. Miller synthesizes his influences into a style of his own, moving swiftly between different modes of expression throughout the story. There’s a swagger to Ronin, a kind of ‘look at the stuff I can do’ that’s replicated in all aspects of the work. Even John Costanza’s lettering, these big and oft sharped-edged balloons, calls attention to itself. Ronin wants to be noticed.

Much of it -- most of it really -- is thanks to the coloring of Lynn Varley: the best of her generation, and a strong contender for the best of all time. Her work doesn’t merely ‘compliment’ the art – it gives it mood and texture. Miller’s pencils are mannered, Varley’s colors are alive. With her color choices she slows time, lightens the characters’ inner lives, and blows the reader’s mind on every other page. The 1980s were a peak period for colorists; not just in terms of talent (though one could argue for Varley, Tatjana Wood and Julia Lacquement as unsurpassable giants), but in terms of overall ideology. These works went for the big, overdramatic, neon-lit, garish, 'fuck realism' type. They didn't show how the world looked, they showed you how it felt. Varley, throughout Ronin, keeps the reader engaged in the emotional stakes. Even when Miller’s pencil work grows distant, more interested in playing up layouts and showing off to the readers, she keeps it human.

Ronin is a work of absolute control. Aesthetically, it’s as good as anything Miller would produce later. Yet everything about it that showcases Miller’s strength as an artist also reveals his limitations as a writer. It’s the kind of thing that you can only do when you are very young, very talented, and very lacking in people that would tell you "no". Both Miller and Varley were very young and very good – and they knew it. The big difference was, Miller made this ‘young genius’ into a show, a persona. Varley chose to let only her work speak for her. The result in that Ronin feels entangled only in the personality of its writer-artist, because he keeps telling us about it on the page.

In Ronin, one can easily see hints of things to come in Frank Miller’s career. Some of it is surface level – the cyberpunk setting of Hard Boiled, or a shot of the Ronin astride his horse that brings to mind Batman in the climactic issue of The Dark Knight Returns. Others are more career-defining - the look of the people, beaten and broken-faced, all ugliness on the inside and out, would mark Miller’s subsequent work with its ‘beautiful ugliness’ aesthetic (even the chiseled Spartans of 300 have faces that look like ground meat). Likewise, the notion of the city as modern hellscape divided between warring clans: you can see it in Sin City; Give Me Liberty; Hard Boiled.

It is the latter that retains some particular interest, considering how Miller’s storytelling has evolved (or failed to evolve), and what themes he returns to over and over again. Kim Thompson’s 1983 review in issue #82 of The Comics Journal, an outlier in terms of negativity, was at least somewhat correct when he claimed Miller was “headed straight for an arid no man’s land of mannered, disjunctive storytelling put in the service of second- and third- hand experience.” This is both true and not. True, in the sense that Miller was heading for the land of ‘second hand experience.’ False, in the sense that -- for him at least -- that land was far from arid.

Thompson was right in predicting that the more experienced and stylized Miller became, the more distant he was from human experience. His Daredevil now feels oddly down-to-earth. His Batman was a god, reshaping the world in his wake. His Spartans: a group of übermenschen, challenging history and turning it myth. The various protagonists of Sin City are noir archetypes – blown up and out of all proportion.

This tendency is even more pronounced in Ronin - partly because Miller was given so much freedom to invest himself in his work, and partly because he was excitedly pilfering from a different culture. An image from Comic Book Interview #2 shows Miller staring intently at the reader while sitting beneath a Shogun Assassin film poster, trying as hard as possible to ape the harsh gaze of lead actor Tomisaburō Wakayama. There’s something oddly appropriate about this American man standing beneath a poster for that particular film, an edited and dubbed version of real Japanese cinema, chopped up for American taste. This isn’t the real thing, not even close.

The scene is equal parts charming in its earnestness and embarrassing in its awkwardness. Likewise, Miller’s talk about the samurai ethos - he speaks not as an author, but as a fanboy. Yet this same fannishness, which Thompson so derided, turns out to be one of the best things about the series (more on that later). Miller’s strength, as an artist at least, is in his excitement. His total commitment to the project. You can almost understand his tendency for powerful, near-fascistic figures of world-changing power. Wasn't Miller himself that type of figure in the 1980s? Here he is, changing the American comics industry, forcing the company to serve the artist’s will, with his sheer talents. Here he is, a rōnin, leaving master Marvel to serve his own ideals.

Slash and Burn

The story of Ronin is divided between two periods and locations: old Japan and future America. In the past, a nameless samurai fails to save his master from an evil demon and must make amends by dedicating his remaining life as a Ronin to hunt the demon down. In the future, the Aquarius corporation develops new technologies with the aid of super-computer Virgo, and Billy Challas, a young man born without limbs, but with tremendous psychic powers.

Miller’s not-too-subtle (nor entirely wrong) point is that America isn’t as different from an ancient society as it wants to be. The so-called bastion of progress reproduces the worst values of old Japan, simply masking them in different terminology. Thus, there is no daimyō's castle from which peasants are forbidden. Instead, the future New York that Miller draws is dominated by the Aquarius complex, which no outsider may enter. In future America, no samurai is lifted above commoners simply by accident of birth; however, any person we see outside the complex is a poor wretch with seemingly no chance of advancement or social mobility.

Its debt to Lone Wolf and Cub aside, the choice of the Ronin as a protagonist is also in line with Miller’s heroic ideals. He likes his heroes to be outsiders to the system, while still serving it, at least notionally. Batman and Daredevil are the most obvious examples, but the most odious is probably Leonidas in 300, a story in which the literal king of a nation is played as the upstart outsider, standing up to the rules of the country in the name of greater good. Society, in Miller’s works, must be saved from itself by those who are strong enough to make the call – who are made ‘other’ by the mere fact that they are too strong to be contained.

Actual 'others' in society don't interest him as much - individuals rather than groups. In Ronin's New York, the city is divided into warring factions, often across racial lines. But there's no ideology in this division. It's just struggle for power. A subplot shows an Aryan nation gang on an even moral keel with a rival group calling itself the Black Panthers. There something of an odious 'bothsidesism' to the world-building. The Ronin is better than gangs because he is above the fray; he doesn't need to worry about these people. Society needs to be saved in the abstract, but Miller doesn't really present any person worth saving outside the Aquarius complex.

The critic Joe McCulloch once referred to Miller's "Cannon Films" aesthetic, which seems as apt description as any - urban blight as a spreading sickness (the inverse of Virgo's creeping techno-control), and the city as a war zone. It justifies any violent action our protagonist takes as a natural response, and makes complex problems into something simple one can simply cut his way through.

Masters and Servants

The rōnin, not just this particular character but the model as a whole, is the perfect Miller vehicle – the master figure must die to justify the character being ‘dishonored’ (on a social level), while keeping his personal honor (in the eyes of the readers). Ogami Ittō, the lead of Lone Wolf and Cub, never pretended to be a hero. His journey was that of personal vengeance, and he never hesitated cutting down anyone who stood in his way. He didn’t care for honor, certainly not the preservation of his society. His enemies were often honorable people, by the standards of their time, who were defeated because they lacked Ittō’s moral flexibility.

The most interesting things about Ronin, at least in story terms, is the metafictional stuff. This probably wasn’t what Miller was aiming at, but due to above-mentioned fannish nature of the project it bubbles up. At a certain point, the head scientist of the project tries to stop the selling of weapons made from his technology, only to be told, in so many ways, that it was done on a ‘work for hire’ basis. And what is Virgo, the machine running this whole damn charade, if not an example of a corporation transcending the creators, and even the managers? The demon Agat, like an empty suit, thinks he’s in charge; only in the end does he realize that he was just a plaything of something far more vast. A series of double-page spreads, appearing throughout the story, show the slowly growing Aquarius complex literally taking over the city - burrowing downwards and sidewise, turning everything into a part of itself.

Consider Miller’s lament, in a pre-publication discussion in Comics Interview #2, that “we, modern men, are ronin. We are kind of cut loose. I don’t get the feeling from the people I know... that they have something greater than themselves to believe in.” This, again, feels like a person venting on the industry. You come in, young and full and enthusiasm, and in the process of making it you lose that idealism. Your publisher turns from a saint to a demon - no matter how much you give to the corporation, it will never love you back. Miller ends the interview claiming he will never make another Daredevil comic again (this will be proven false, in due time). Of course, Miller loves the feeling of being a rōnin; he wants something to believe in, but it’s not another master. He wants to be his own master: to avail himself of creator’s rights.

What of Billy Challas, the kid who took on the form of the Ronin? He’s the story’s masterstroke. A young man, shunned by the world, madly in love with a woman who is unavailable (and would never think of him that way). Billy feels like an exact representation of the ‘typical’ comic book fan. Lost and confused, he reaches out for the one thing that gives him comfort, a televised fantasy show from a foreign land, and literally makes it into the base of his identity. Frank Miller not only made one of the first otaku comics in the west, he made it self-aware.

Billy makes himself into the Ronin, into this cool badass figure that kills the bad guys and gets the woman (Casey, the head security officer who seems to be on the ball until the Ronin arrives, at which points she turns helpless). Using his powers, he wills the illusion into reality - he wills nerdom into being the dominant cultural force. It’s no wonder that the Ronin is this shallow caricature, something that Thompson commented upon based on issue #1. The story at first makes you think the demon is the problem, only to slowly reveal it's Virgo; and just when you think you are so clever for figuring it out before the text fills you in, it tells you the real problem is Billy. It’s you, the person who keeps buying into these cool fantasies; it’s Frank Miller, the man who keeps selling them to you.

The only way to win is to shatter the illusion, and the only way to shatter the illusion is for the Ronin to lose. Not in some great heroic combat; to lose because Casey beats him to the punch of killing the demon. She mocks him, pushing just the right button by telling the Ronin a woman had to do his job for him (remembering that Atwood line about “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”).

This is how the story ends. With the big macho man hero losing out to a black woman, crying like a child as he commits suicide in an act of cosmic tantrum that destroys everything around him. The resulting fold-out image is still stunning to behold. It’s somehow both abstract and precise at the same time, the colors changing throughout as the effect of the blast grows ever-stronger (the only thing close would be the infamous destruction of Neo Tokyo in Akira). It’s a striking prediction, and encapsulation, of the male nerd mindset in the 21st century. The geeks control the world -- the world of culture at least -- but they still feel like losers when all their dreams have come true.

This could’ve been a perfect ending. Could’ve, but wasn't. It actually ends after the explosion, with Casey looking up and seeing the Ronin, somehow alive again. Was he real all along? Did he became a separate entity, due to Billy’s psychic outburst? Is it actual magic (something that the story mocked so far)? It doesn’t matter. What does matter, is that after everything we’ve been through, it ends with a woman looking up at a big strong man. It ends with the illusion affirmed, rather than denied. Frank Miller’s career after that, for all his superior and evolving skill as both an artist and a storyteller, would remain in the shadow of that fantasy he failed to kill in 1984. Forever a fanboy.