When the Great Depression put cartoonists’ jobs on the block, Jimmy Swinnerton, a friend to William Randolph Hearst who had the Chief’s ear, lobbied for his colleagues. Occasionally, he was successful. In November, 1930, Swinnerton reminded Hearst that Jimmy Hatlo, creator of the panel They’ll Do It Every Time, was a “big shot on the paper and might have his financial rash cured by some salve but not too much.” Swinnerton’s plea worked; Hatlo received a raise and kept drawing his popular comic for Hearst’s King Features.

Yet even Swinnerton was unable to help his young protege, a Los Angeles Herald cartoonist named Austin “Pete” Peterson. Swinnerton and Peterson were close; Peterson had even dated Swinnerton’s daughter, until the girl threw him over for a college boy. Swinnerton once had stepped in to help Peterson find work with Hearst, and in November, 1930, he stepped in again to help Peterson keep his job on the Los Angeles Herald’s sports page.

Wrote Swinnerton in a telegram to Hearst:

PETERSON THE SPORT CARTOONIST FIRED FROM HERALD STOP HE IS THE CHAP WHOSE WORK YOU LIKED HE OUGHT TO BE PLACED SOME PLACE AT DECENT SALARY HE WAS ONLY GETTING THIRTY AND WAS OUT FOR ASKING FOR A RAISE REGARDS = SWINNERTON

It was no use. Hearst wrote back the very same day. “Dear Swinny,” he penned. “You know that certain economies are necessary in these days and that space economies are just as important as any other.” Peterson might be a “nice young man,” but Hearst deemed him inessential to the Herald during an economic crisis. By asking for a raise, Peterson sealed his fate. He was canned from the Herald, never to work as a professional cartoonist again.

After leaving the Herald, Peterson found greater success in radio and television. Now, a remarkably healthy one hundred-and-eight-year-old who greets visitors with a firm handshake, he can recall his radio and television work with a keen memory. His youth in comics, however, takes some excavation. “Jimmy Swinnerton,” he says during an interview in his home in Desert Hot Springs, California. “My God, that was a long time ago.”

As a Palo Alto high school student, Peterson found early inspiration from a neighbor, the writer Maxwell Anderson, as well as the young Stanford University student John Steinbeck, whose literary bull sessions Peterson attended but “they were too deep for my high school brain,” Peterson later wrote in a memoir. Also in Palo Alto was Swinnerton.

“Swinnerton was a wonderful guy,” Peterson says. “He had the cartoon Little Jimmy, which was very popular at that time. He was a great instructor for me. He took me out of high school and got me the first job.”

Peterson aspired to be a reporter, but had been drawing cartoons for his high school paper. Swinnerton suggested that Peterson show his work to two Hearst papers: the San Francisco Call, which didn’t bite, and the Oakland Post Enquirer, which did. Peterson landed his first cartooning job at the Post Enquirer for fifteen dollars a week, plus free tickets to all the wrestling matches and football and basketball games he could take in. “I did sports cartoons,” Peterson remembers, “which was good because you got in all the games. There was a cartoonist on the opposite paper, they kind of competed about space. He’d get a little bit like that, and then I’d get a little bit like this.” Peterson widens his hands. “And then all of a sudden I had half a page.”

All this time, Peterson had Swinnerton at his side, giving him pointers. “He kept me from making mistakes, mostly. He was a great help. He was critical, very critical, which was good, because I needed it.” Peterson soon received a telegram from Hearst, calling him to the Los Angeles Herald and doubling his salary.

It was the late 1920s, and Peterson threw himself into Hollywood society, rooming with Francis Scheid, later a sound man for Casablanca, and frequenting late-night ballrooms with a chorus girl on his arm. The first movie star he met was Marion Davies. “One of the little extra duties we cartoonists at the Herald and the Examiner inherited was to draw individual place cards for her parties at her Santa Monica beach house,” he wrote in his memoir. One day, he hand-delivered the cards and received a plate of cookies in return. “I never got invited to any of her parties, though.”

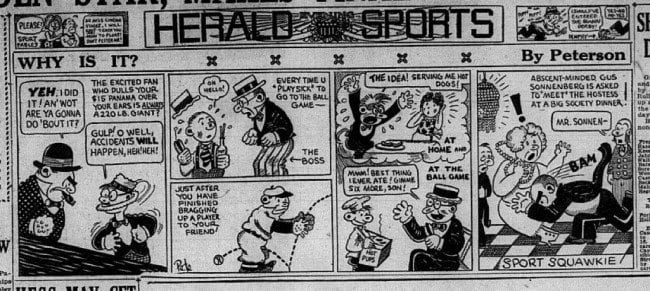

At the Herald, Peterson launched a series of screwball observational comics often starring round-headed, bulb-nosed saps who dangled on the string of bad luck. Peterson’s Why Is It? series featured single-panel gags about embarrassing moments, such as getting your panama hat pulled over your ears by a ballpark bully, or playing hooky and encountering your boss at the big game. Other series went by the titles Pathetic Figures and Sports Talkie, the latter showing Peterson’s interest in bringing ideas from radio and movies into his strips. Among Peterson’s wryer submissions was “How to Be a Radio Announcer”, depicting an announcer trying to jazz up a lackluster sports scene. One helpful tip: “A good way to do is get hold of some oldtime fight stories and just read them off!”

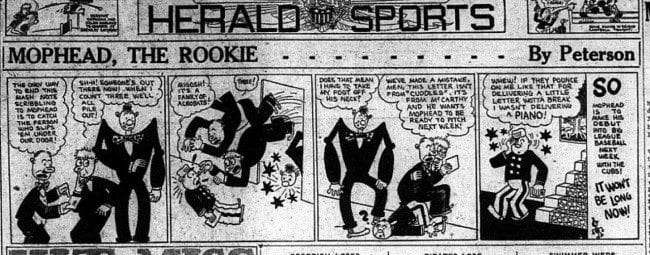

Peterson developed a recurring character, Mophead, the Rookie, a lovable country rube at loose in the big city. “Mophead, the Rookie, he was a cartoon character that was a farmer type who became a baseball star,” Peterson recalls. “I only did it for one week then I had to do it all the time because it was popular.” Mophead, the Rookie, Peterson now likes to point out, preceded Al Capp’s own lovable rube Li’l Abner by several years.

More than eight decades after his time at the Herald, Peterson still recalls the newspaper art room as place of easy camaraderie. “You got to go to all the games, get to know the guys. ... You’re preserving their view of life.

“One cartoonist helped another in those days,” Peterson adds. “It was a nice fraternity.”

Peterson also remembers the one time he spoke to the acknowledged giant in the business. “Tad Dorgan,” he says. “Oh yes, the best. I admired him, because I thought he was the best of the sports cartoonists. Everyone said he was a nice guy. He talked to me one day on the phone and gave me some instructions, which helped me because I was just a kid starting in.”

Yet even with help from Dorgan and Swinnerton, Peterson experienced a few of what he later called his “calamities.” The first came after a particularly long night at a party in in Malibu Canyon. The next morning, hungover, he submitted a comic featuring an armless Mophead. Even worse, Peterson recalled, was the time he sloppily inked a caption over Mophead’s head. He had intended it to read, “Mophead stood there flicking the ball across the plate,” but Peterson’s “L” and “I” regretfully merged to form a single “U.”

Yet Peterson’s biggest calamity was asking for a raise. Not even Swinnerton could save his job then. Booted from the cartoonists’ fraternity, Peterson went on to enjoy success as a writer for Fred Astaire’s radio program. During World War II, he served as a head of programming for Armed Forces Radio, working with top stars and sending the recordings overseas to entertain the troops. (A photo from this time shows Lauren Bacall looking admiringly at Peterson.) After the war, he joined the Ted Bates advertising agency, producing shows including the Colgate Comedy Hour. He was in New Orleans in 1955 to produce an episode featuring Louis Armstrong when he met his future wife, Maxine. She was twenty-five years his junior; she remembers that her friends and family were dismayed at the marriage, but the couple is together still. They celebrated Peterson’s one-hundred-and-eighth birthday this summer with a quiet party, Maxine placing a single candle on Peterson’s favorite dessert, strawberry shortcake.

Peterson never published another comic after leaving the Herald, though he’d often draw cartoons in his letters to Maxine. (“I hated to write,” Peterson admits.) His early work as a cartoonist is largely unnoticed, and Mophead, the Rookie has, until now, never been republished. Yet Peterson looks back on his cartooning career with fondness. “It was more fun than radio,” he says. “Because you got complete control over what you do. In television you don’t; you read a script or something. When you’re by yourself, it’s different.”

Peterson’s eyes still shine at the memory. “Those six columns across the paper meant freedom to me,” he says.

Austin Peterson’s memoir, Television is a Young Man’s Game? I’m 94. Why Didn’t Somebody Tell Me? was published by Writer’s Club Press in 2000.