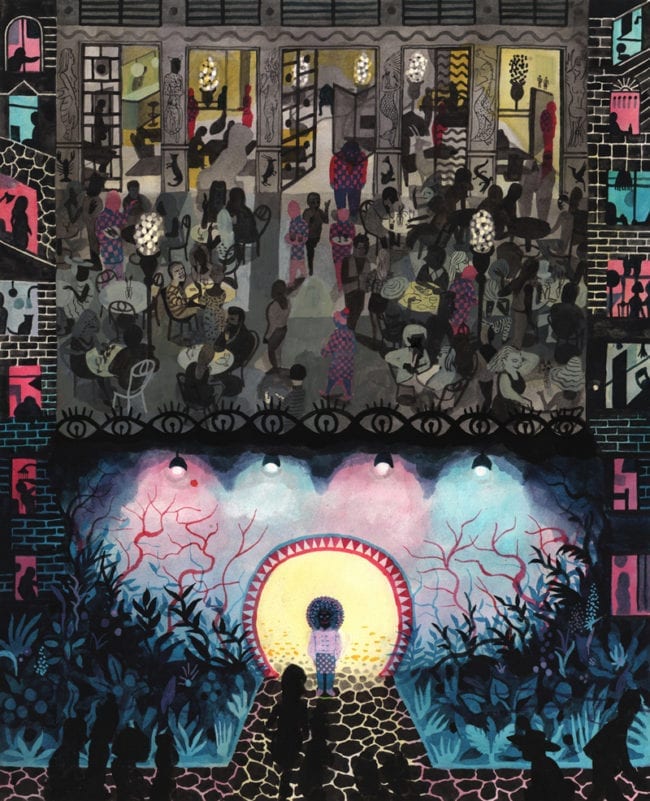

No one who sees Brecht Evens' art forgets it. He wants to excite people about the life around them and he knows how to do it. His tool is color, a highly personal mix of inks, aquarelle, and markers. Evens uses them in layers, playing with the luminous white of the paper underneath. With bright, radiant hues and multiple depths of dark, the universe he creates is flamboyant yet engaging. His new book, Les Rigoles, plunges you into it for 336 pages.

This is the Flemish artist's fifth major book. It succeeds 2010's Les Noceurs (The Wrong Place), 2011's Les Amateurs (The Making of), 2014's Panther, and a 2016 Louis Vuitton Travel Book on Paris. Each of the three graphic novels has received awards. Les Noceurs won the founding Prix Willy Vandersteen, an Oscar for comics and graphic novels in Dutch. In 2011, the same book earned Evens the Angoulême Festival's Prix de l'Audace – a prize for adventurousness.

His latest work is even more audacious. It's a visual tour-de-force that's clearly keen to burst all boundaries. The book contains not just Evens' trademark watercolor but also pages made with several lithographic methods. Its graphic invention, almost dizzying, is refreshing for its utter tirelessness. Navigating by taxi lights, pearls in the dark and nightclub mirrors, the pages sweep the reader through a crowded city between dusk and dawn.

For this single night, its narrative follows three characters and a large supporting cast. The book's protagonists, Jona, Rodolphe, and Victoria, might have come out of a film by John Cassavetes – only over many pages do we sense who each might be. As with Evens' Panther, whose title character brought yellow into the story, Les Rigoles is color-coded: each protagonist has a single primary hue.

Things begin as Jona, who is drawn in blue, sets out for a final night on the town. Everything he owns is packed since, in the morning, he moves to Berlin. Victoria (drawn in yellow) begins her night surrounded by her self-appointed protectors. Then there's Rodolphe, whose signature is red. Once a king of the dance floor, he now suffers from depression.

By chance, all begin their evening at the same location.

In the real Paris, "Les Rigoles" is a modest café three minutes' walk from Brecht Evens' flat. His Paris aerie is tiny and sits atop a hill. To reach it, you have to climb seven flights of stairs. There's no elevator but Evens does enjoy a grand view of Paris.

Surrounded by piles of papers and shoes, we're seated there today. For the artist, it's a pause between almost continuous signings. Les Rigoles is on display in every Paris bookshop and its Dutch twin, Het Amusement, has just debuted. In a week, Evens' art is also going on show.

The artist resembles one of the Three Musketeers – or he would if one of that well-fed trio was a beanpole. Although his presence on the Internet is a large one, it doesn't really capture his goofiness or his erudition. The artist answers questions slowly and thoughtfully and is an attentive, highly articulate speaker. As his French editor puts it, "His imagination is very rich and complex, very cultivated… and he knows exactly how to put that across in his work."

Evens' last publication was Paris, the Vuitton art book. In producing its 168 images, he referred to just a handful of photographs. All were taken in the crowded Passage des Panoramas, to help the artist replicate its chock-a-block signage. Otherwise, from the métro to the "Museum of Hunting and Nature", Evens worked straight from life. His results were stunning: a riot of color and observation that privileged views, signs and details familiar to actual locals.

Vuitton's press handout hailed the work for its "fertile chaos" and Evens describes the project as "a playground". But, in fact, the chaos had been all too real. Back in 2013, as he was making Panther, Evens' life was suddenly derailed by a mental crisis.

He was not meant to do the book on Paris; his initial contract with Vuitton was for Tokyo. "But that had been planned before I went nuts, so the trip to Tokyo was a spectacular failure," he says. "I was sent out there but then there was this climax of craziness – and things had to be shut down. During my recuperation, I spent time in Paris. I was finishing Panther and wasn't in great shape."

Yet this was where Les Rigoles got its start. "The germ," says Evens, "was just me coming back to life. A state of depression never carries any potential or interest. Then, once the interest starts returning – bit by bit – it's like you're back at zero. At that point, it's just lines in old sketchbooks, dreams you have, something you happen to see sitting on a terrace. Because it's so surprising to have ideas again, you notice every little thought and you get them down in a sketchbook."

In 2013 and early 2014, he says, "things were so messed up; I couldn't ever have considered such a massive project. The book is a product of peace having descended. The biggest thing that happened during its making was the girlfriend I found. Having one important book and one important woman, it became much simpler for me to prioritize. But, in terms of what I actually wanted from the project, there was no big sea-change."

The book has clear inspirations. One of these is Paris the city, the place where Evens moved four years back "on an impulse." But the other is his very first book, The Wrong Place. The artist sees Les Rigoles as his debut's "big brother." "Once I knew it was gearing up to be a nightlife book with three characters – a woman and two men – I realized there were going to be some very basic similarities. So I decided I would lay them on thick… I repeated some of the images, pretty much using a ruler."

He tilts the screen of his laptop towards me and, on the left, there's a page from The Wrong Place. It shows the book's protagonist, Robbie, leading a conga line across the floor of 'Disco Harem.' To the right, the low-lit scene is replicated with Rodolphe. This time, I know from having read Les Rigoles, the dancing is a memory. But the character right behind Rodolphe is … Robbie.

"We're in exactly the same place," Evens tells me. "But these two images are charged with very different meanings. If I superficially accentuated their resemblance, it was just to make those differences pop out. The Wrong Place was an anticipatory book; it has the vision of nightlife I dreaming up then. But I don't want to call it naïve. Because I was 22 and, from a 22-year-old, it was a cynical book."

If some places haven't changed, they are seen from a new perspective. "Disco Harem, for instance, was always an endless place. This time, I wanted the endless place to be that city around it. Also, The Wrong Place was a very binary book; its motor was just this idea of 'popular'/'unpopular.' Hopefully, this one is a much bigger appreciation – of the city and all those things that make it up."

Les Rigoles is indeed a big idea and, from the start, it had a cast to match. "While I was doing the travel book, sitting around in cafés and drawing, I thought, 'I'll make some panorama of the city where there won't even be a narrative. Where countless characters just appear and disappear and we don't have the time to follow their paths.' Just a celebration of the fact that, by happenstance, I'm living in this big city and I'm loving it".

But the hypothetical cast of a thousand characters narrowed down. "I found myself with fifteen interesting puzzle pieces. Some of those got fused together and others disappeared. Some were relegated to extra status while others came to the fore. But I had a lot of fun with secondary characters. Because they don't have to represent so much, you owe them less…you can relax a bit and go a little wild."

The basic conceit, however, never changed: Evens was aiming to put a world between two covers. "I wanted something like a paperback copy of Balzac, a whole world that would be portable. But, instead of just one city, I wanted to make it a kind of European amalgam." As his ideas came together, he began to organize. For, despite seemingly effortless shifts of style and character, Les Rigoles was planned with a military precision. As it expanded, so did Evens' key resource – his heavily annotated pile of black-and-white storyboards.

These, he says, were realized "very unchronologically." "When I storyboard a scene, most of the time I'll start drawing almost immediately. I like to do it when the creation of something is fresh. But this time, especially with the big set-piece drawings, I often had a sketch I carried around, fleshing it out with little details and phrases. It could take a year, it could take two years…because I always knew that more was going to be added. I didn't want fancy graphic vignettes that might interrupt the narrative. Plot had to go on and character needed to continue and they had to be fully part of that."

For the restaurant in the book, where much of the action happens, he made a precise floor plan. "I knew who was at every table, I knew what they were talking about. Because all three of the main characters start their story here and it's two hundred pages before the last one leaves. So it needed to have a sense of knowing where you were. The reader won't notice that there's a program, that I mapped everything out. But, as long as we're in that restaurant, they'll have an unconscious sense of knowing where they are, of feeling somehow moored."

When he plonks the well-worn stack of storyboards in front of me, I'm impressed. It's a big pile that has to weigh five or six pounds. But Evens says he kept it with him every minute, every day. "It got to the point I couldn't go out and buy bread without it… I was so sure I'd see or hear something I'd want to inject, in a specific spot."

The strategy, although cumbersome, helped him avoid "long detours and mistakes". It was especially useful since his narrative ricochets between three characters. "I'd never done a book where we follow three people like that, where it's woven together 1-2-3-3, 2-1-2-3, and so on and on. So what I sometimes did was take this pile of papers, then re-arrange it by character… Just to check out what might happen with a different narrative arc. Or I would read it again to see how the characters alternated, to think about how this choice or that one might alter the rhythm."

The method also served to discipline his graphic facility. "One example is the second half of Rodolphe's story, where he's in a manic state – or what I interpret as one. I had some pages with these escalating chains of adventure, all these escapades that we were going to see him have. They were very attractive occasions for graphic showmanship and they were making eyes at me for literally years … Come on, draw me – it's gonna be fun! But all those, at some point, got stripped away. I replaced them with a little personal theme, one that better captures the rapport between a manic person and the people close to him."

"Only by postponing the drawing of those pages did I realize what I needed was really something small."

Over the four years it took him to create the book, there were many side projects. For the fortieth birthday of his French publisher, Actes Sud, Evens executed a fresque in a never-ending pattern. For the Flemish Literature Fund, he made a map of lyrical poetry. For the French company Cotélac, he designed fabrics. There was a mural that went up Brussels (this is his second mural; Antwerp already had one). Halfway through 2017, the in-progress Les Rigoles was also shown at Brussels' Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art or MIMA.

The new book was written in Dutch and French, "with a few scenes in English." But it's heartening to report that its creation was analogue. "All the drawings were done on paper and I write by hand," says Evens. "So the creative parts are all computer-less. Where the computer comes in is for research; when I want things to be 'right' or inspired by actual stuff, then I'll look something up. Because if my wildness ever turns into the norm, if there's nothing solid, then that wildness loses its effect."

Evens has spoken before about how he forged his style, learning to work directly on the page in color. He still paints from light to dark using Talens' Ecoline inks. But he also continues to experiment. "Ecoline dominates, but I use a mix. Now I have some different inks and, with the same brush, I'll also pick up gouache to make it what I want. Or, I'll mix it with real aquarelle. It all depends on what I'm searching for, what opacity or transparency I need to have. There will also be some pastels and, often, markers."

Les Rigoles varies not just in style and color but also in its textures. Its lithographed pages came out of Evens' relationship with artist printer Michael Woolworth. Born in America, Woolworth established his Paris atelier in 1985. In 2012, it was recognized by the government as an Entreprise du Patrimoine Vivant – part of the "living heritage" of France.

Asked to collaborate by Louis Vuitton in 2014, Woolworth and Evens have kept on working together. "We just got along really well," says Evens, "and we had fun. So we started inventing other ways we could work together. Pretty soon, we were doing stuff for Les Rigoles."

Readers will have a field day with allusions in Evens' art; they can find medieval artists, Giotto, Bruegel the Elder, and Picasso. But the book's rhythm and personality are all its own. Evens says it gained from everything around him, "probably every time I was struck by a phrase or an image."

He also mentions M.C. Escher, his own manic drawings and the 2016 Paris show of Utagawa Kuniyoshi. "I don't go to many shows and I nearly missed that one. I went on the very last day and waited in the freezing cold for an hour-and-a-half." He says the Japanese master didn't influence his lithographs. "It's been more of an influence in some of the drawings. It motivated me explicitly to avoid confusing transparency and error."

The book's real gamble, Evens suspects, is its plentiful text. This includes long and fantastic disquisitions, almost all of which are voiced by secondary characters. These work in tandem with the reactions they elicit. But, from an artist with less confidence in his writing than his visuals, they constituted a leap. "Maybe it was risky to have put some of that in. For instance, starting Victoria's story with a four-page dialogue – more like a monologue – where one of her friends is relating a dream... What he's saying doesn't matter in any narrative way, it's there to bring out the characters of those who are listening."

Most of the longest soliloquies come from a taxi driver. "Those are little, contained nuggets of fiction-in-the-fiction. While the characters listen to them they are protected, they're safely ensconced in the carapace of that cab. But they're soaking in what we think adventure is. The build-up to it is almost like a joke, because every protagonist ends up asking the very same question... and it provokes the taxi driver to improvise."

Evens' chief concern was balance, maintaining the book's pace while preserving its equilibrium. "I paid attention to how I drew every character. That isn't necessarily a matter of — for example — whether they are listening or not listening. If you take a trick like making the face disappear, that will have some kind of closed and distant effect. But, in different contexts, the same trick will mean different things. What kind of detail I put forward or hold back…by the moment of drawing, I've consciously thought it all out."

Some of the book's characteristics are less about the stories being told than about the author's view of reality. "When you see characters hearing or not hearing each other, that's not necessarily some kind of theme. It's more about the way I understand conversation. Even in a really good, focused interchange, if you listen back to it, you're probably talking through one another, each thinking of what you're going to say just as much as 'listening.'"

"A lot of people, when they write dialogue, just go 'A, B', 'A, B', 'A, B.' They'll have the characters neatly wait their turn. Whereas I don't think our brains really work that way. In reality, it's more of a constant traffic jam – even when we like each other and we're interacting well. When we're interacting less well, it's more extreme."

Evens has talked a lot about wanting to lose control. He's said he likes watercolor because it's hard to master and because it produces mistakes. But when he says "mistakes," he means something quite specific. "The kinds of graphical accidents that I was talking about, they're actually representations of something genuine. When I draw the jumble of the city or I draw nature… This is a simplification, but… errors, spots and little incongruities make it more realistic. Because when you're in a space and you start to look around, you don't take in the whole. You can't. You don't see the world around you like you see a postcard; it's not organized that way. We're moving, others are moving, and the eye makes constant choices, it decides what to interpret and what to identify."

"So at any given moment, there's a lot of mess in there and, for me, this kind of mess has to stay in. It's controlled; it's never like I'm creating randomness. It's just that incongruities seem to catch the eye better. They're more natural and they latch onto the eye more realistically."

"Maybe I do play with a lot of stuff," he adds. "But I only do it when it serves my narrative. It's all part of calibrating things. When I use a lot of detail, it's very calculated – I'm making sure it doesn't obstruct anything essential. Giotto's kind of a fun example in that respect…He wants to show you a city and he wants big buildings. But Giotto also wants to have large figures, so he makes the street tall and has a very tall ground-floor. Then he makes the first floor smaller and the second even more so. And so on and on; he'll compress the actual buildings to create a visual hierarchy."

The buildings, the city where Les Rigoles takes place, are never specified. But Parisian readers have all assumed that it's Paris. "They had reason to," says Evens, "because I mentioned Belleville and a couple of other places – and because there is a real Rigoles. But, for the Dutch version, I changed some of those names and I probably will for the English one, too."

"The fun result would be for everyone to think it's their city."

The best adjective for Les Rigoles is "unexpected." It's a maximal tome of praise for the city with a striking evocation of the urban night. It's also a masterful interrogation of its medium. But the book never hides the question at its centre – just how real is the promise of all that neon? Even as it tantalizes the eye with possibilities, its main characters stay blind to most of what's around them. "Those characters," says Evens, "don't manage to pluck the fruits the city seems to offer. So it's a celebration of life but it's one that features people who have trouble celebrating."

He looks up. "The themes may be heavy, but I hope the treatment is light. Don't forget to mention it's full of gags and jokes!"

• Brecht Evens - Les Rigoles is on show at Galerie Martel in Paris from October 26 to November 24. The vernissage takes place October 25, from 6:30 pm. On Saturday, October 27, from 3:30 pm., Evens will be present at the gallery for signing. His work is also the subject of a show in Arles, Brecht Evens: Disco Harem from 28 October to 23 December

• The English translation of Les Rigoles, The City of Belgium will be published in May of 2019 by Drawn & Quarterly