“Ebisu is secretly one of the most wigged-out artists on Earth.” – Gary Panter, Hilobrow

I have a new love: The Pits of Hell by Ebisu Yoshikazu. This collection of surreal and savage manga stories drawn in a naïve art style vibrates on my bookshelf and issues forth the sounds of thumping pachinko machines, clattering speedboat motors and roars of rage so intense there is no doubt in my mind they have the power to rip my head off. These stories are screwball, haunting, mystical, shocking, hilarious, frightening, and sad—usually all at once.

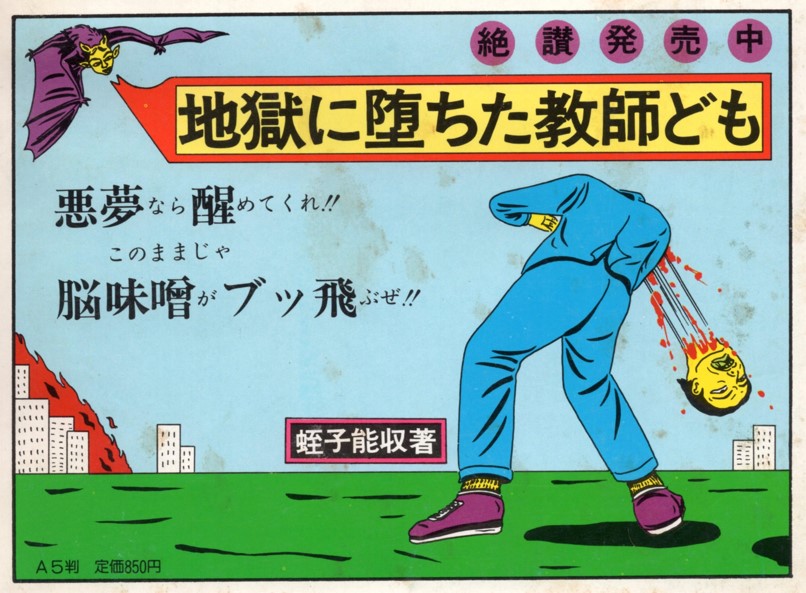

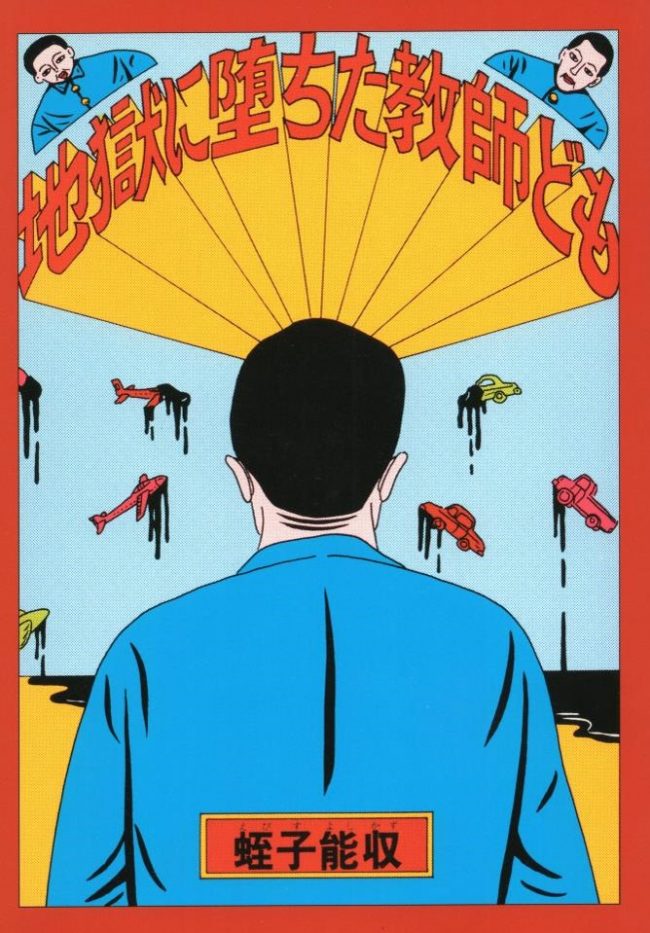

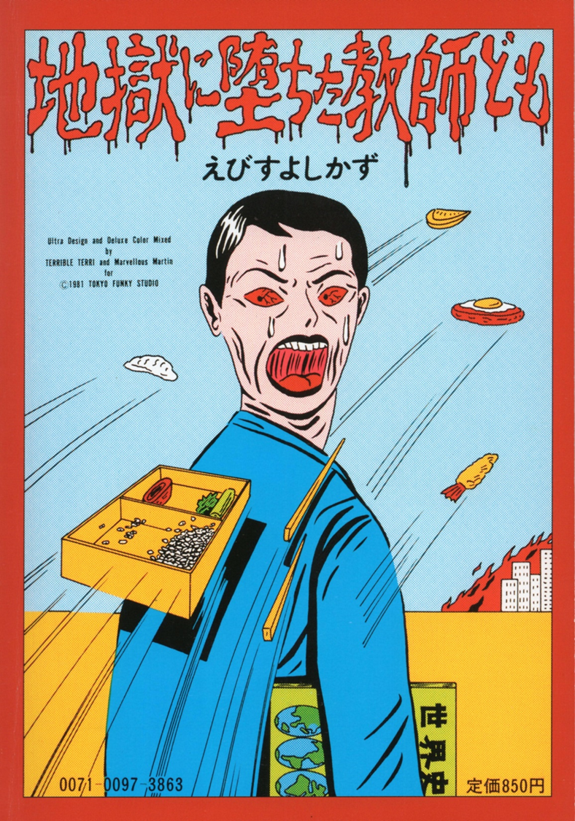

The Pits of Hell has actually been around for almost forty years but only in Japanese. Originally published in 1981 in Japan as Teachers Damned to the Pits of Hell, it became a cult hit selling an estimated 40,000 copies up to 1990. The book is regarded today as a seminal work of the heta-uma (bad-good, as in “so bad it’s good”) art movement. Some English-speaking manga fans have wondered for years about the bizarre and evocative advertisement for the collection depicting at odd angles a man’s messily severed head knocked from his body as a human-faced bat looks on and a city burns in the distance.

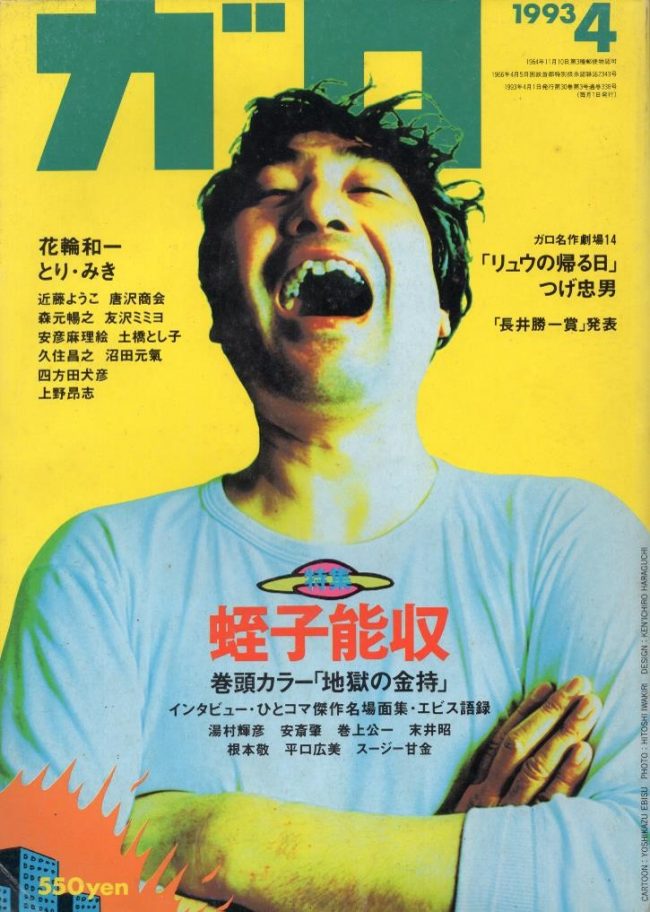

The Pits of Hell contains nine short stories published between March 1974 and June 1981. Seven of these were originally published in the highly influential monthly magazine Garo (1964- 2002) with one each from Jam and Manga Piranha. The simple and elegant 2019 paperback edition offers very brief, cryptic commentaries by Ebisu, an introduction by 1970s Garo editor Minami Shinbō, and an in-depth, top-notch essay by manga expert Ryan Holmberg, who also translated the book into English (thank you, Ryan!).

This eyeball-searing new edition comes to us – in an undoubtedly low print run (so grab it while you can) from London’s savvy purveyor of manga, pop art comics and delicious obscurities, Breakdown Press, publisher of several Holmberg projects, including the exquisite Hayashi Seiichi’s Pop (2016) which crosses over a little with The Pits of Hell in that both cartoonists were inspired by famed Japanese graphic artist Yokoo Tadanori, as Holmberg informs us in his written essays for each volume. The bizarre, seminal work of Ebisu was high on Breakdown Press’s list of projects. The book’s designer, Joe Kessler (an experimental cartoonist in his own right, see Windowpane) at Breakdown Press, told me: “Ebisu was one of the first artists to come up when talking to Ryan about what we’d like to publish. His work occupies a very central place in the clustered Venn diagram of our collective taste.”

Finally, in November 2019, the world saw the book’s first English translation published by the London-based Breakdown Press. Thus, the book is new to an English-speaking readership (although lately Americans and Brits are surely familiar with the pits of Hell). Kessler candidly shared with me his opinion about this: “It’s an outrage that we are the first people to publish it in English. I wonder what everyone else has been doing in the thirty-something years since it came out?”

I feel I might become as addicted to Ebisu’s work as he purportedly is to gambling at mahjong, boat races, and pachinko parlors (all depicted in the stories in The Pits of Hell). Ebisu’s work is deliciously and satisfyingly incoherent. Flying saucers zoom around the background unnoticed by the people in the stories. Bullet trains jump their tracks and trundle through crowded cities. Speed boats roar through city streets, ripping up the tarmac. A small pile of salmon roe comes to life and crawls out from underneath a mound of dirt on a table in a restaurant (a surreal image in itself) to cascade onto the back of a drunk man passed out on the floor and transform into delicious yakisoba which the salaryman’s co-workers greedily consume with chopsticks eerily like the piggish parents in the nightmarish opening of Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. In Ebisu’s story, the whole scene turns into a crazy, impossible orgy.

Ebisu Yoshikazu’s stories are as ugly to look at and easy to read as a Jack Chick tract. They slither into the eyes, mesmerize the neocortex with outlandish cartoon imagery, and grip the reptilian brain with pleasure, violence, sex, angst, danger, and anger. Seemingly uninterested (or perhaps incapable of) representing reality, the artwork operates with that appealing, brain-zapping visual language (those ever-present sweat drops!) that could never work in real life (it would be horrific) but which works perfectly in comic art, like the work of Harold Gray (those eyes!), E.C. Segar (those forearms!), Chester Gould (that flint-edged nose!), Robert Crumb (those thick legs and posteriors!), Art Spiegelman (those people with mouse heads!), and Ben Katchor (those loose, bent coat hanger lines that simultaneously define bulky men and disassemble them!).

There is, for me, a fascinating resonance in Ebisu’s comics with the delicious surrealism I enjoy in much older American comics. The idea of creatures appearing from nowhere to devour a man in an elevator (“Salarymen in Hell”) is eerily similar to a similar repeated motif of creatures devouring dreamers in Winsor McCay’s terrifyingly comic Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. The difference, of course, is that in Ebisu’s comics no one wakes up from their nightmares.

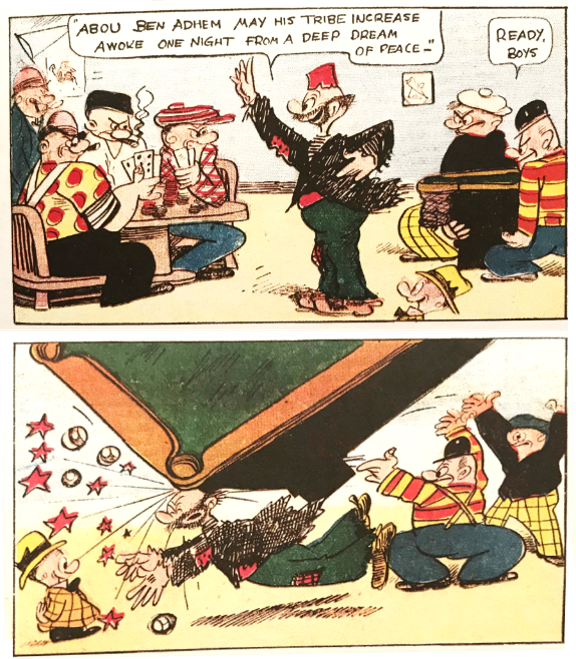

In the calculus between horror and comedy in comics, it’s all about what the cartoonist chooses to emphasize. McCay had to produce seemingly entertaining fare in daily newsprint whilst he explored the demonology of his soul, sifting through the rubble of archetypes in the collective unconscious. A slight shift in emphasis can transform a murderous action like a teacher slamming the corner of a huge, heavy wooden desk into a student’s head (“Teachers Damned to the Pits of Hell”) into a slapstick scene, as in a 1931 Milt Gross panel in which a hobo-poet is assaulted with a pool table when he attempts to recite the Leigh Hunt chestnut, “Abou ben Adhem.” One scene is horrifically funny and the other is hilariously violent; but which is which?

Certainly, Ebisu's work shares DNA with the comics of Gary Panter, Rory Hayes and other cartoonists who create complex, multilayered, and shocking work in a seemingly primitive art style. Of all the weird American cartoonists whose work might be considered to have a "heta-uma" quality, the one I think of the most when I read the stories in The Pits of Hell is the Golden Age comic book cartoonist Fletcher Hanks.

The direct current zap of violence, the obsessive visual tropes that repeat in every story, and the art style that so enchants us with homeliness it becomes beautiful are all aspects the comics of Hanks and Ebisu. An ever-present image in Hanks's comics, found nowhere else in American Golden Age comics, is the nightmarish scene of people in the sky. His vengeful, bloodthirsty superhero, Stardust, is fond of banishing villains to the stratosphere to slowly suffocate and die.

This motif resonates in Ebisu's work, as well, with unexplained flying objects in the sky and, in particular, his striking scene from the front cover of the original 1981 publication of The Pits of Hell which depicts melting automobiles in the sky.

Ebisu’s stories are set in modern Japan, a surreal place to begin with for an unworldly American like myself, but they are about the secret worlds within each and all of us and this makes them immediately accessible. I had to look up what a "salaryman" is, but I instantly identified with the bored, exhausted workers in The Pits of Hell.

Having sampled Ebisu’s world, I crave more. So much so, I could not stop myself from buying the first copy I could find of Comics Underground -- Japan: A Manga Anthology by Kevin Quigley solely because it contains two Ebisu stories in English translation not in The Pits of Hell. These two stories are also satisfyingly over-the-top, WTF weird.

I love that the stories in The Pits of Hell are all unremittingly nonsensical and surreal. The way the real world operates has no place in these stories drawn from the well of the collective unconscious. The boat races that tear up the otherwise pristine streets in “Salaryman in Hell” occur regularly with no explanation of why the boats speed through pristine streets instead of water and how the damaged roadways are repaired for the next race. In “Tempest of Love,” a man matter-of-factly gathers yen coins through breaks in a sidewalk. The stories are full of mundane details juxtaposed in extraordinary and incoherent ways. The impossible details accumulate until the story collapses in often unforgettable bizarreness. Ebisu has said he likes to “tell ordinary stories that self-destruct for shock effect” (Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga by Frederik L. Schodt)

It is probably my ADD, but even the reading patterns of the comics in The Pits of Hell seem to change up mid-story so that I sometimes read the panels out of order. There’s a William Burroughs cut-up aspect to the narratives, which are vividly dreamlike. Minami Shinbō, Ebisu’s editor at Garo magazine in the 1970s, discusses the surreal nature of these stories as their main appeal in the original 1981 introduction to The Pits of Hell (included in the new edition and translated by Holmberg): “What’s interesting about Ebisu Yoshikazu’s comics is that they are our dreams, our repressed desires and that they allow us to be voyeurs on the strangeness of being human.”

The electric jolts of absurdity in Ebisu’s comics are grounded by startling, horrific violence when his characters unleash their repressed feelings. This is the “shock effect” Ebisu mentions. In the title story from The Pits of Hell, a school teacher is alternatively ignored and mocked by his students, most of whom sleep through his class. When a piece of food from a bento box is chopstick-flipped at him, he loses his temper (the back cover of the first edition depicted an entire bento box rocketing towards a demonically angry teacher). Instead of yelling or punishing the student, the teacher beats him to a bloody pulp and then tears his head off. At the end of the story, the rest of the students, now awake, applaud the teacher and tell him, “We’ve always wanted to see you get angry.” The story starts out with a conflict which we expect will turn into something about the miserable life of the teacher, but instead it goes off the rails in a shocking way.

What I’ve described would be horrible in most contexts, but somehow it works in Ebisu’s treatment, perhaps because the dreamlike feeling distances us from the violence and even invites us to look at our own repressed anger and wonder what it might look like if we unleashed it as this teacher damned to the pits of hell does.

Ebisu’s life story reads like a real-life version of his dark comedies. Born about two years after the United States detonated two atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Ebisu came of age smack dab in the middle of a new kind of horror the world had not before seen. His family moved to the devastated Nagasaki when Ebisu was an infant and he lived there until his twenty-third year when he moved to Tokyo. Ebisu drew comics as a boy, most notably to fantasize about violent revenge on paper against those that bullied him.

After years of a dull, drab, soul-icidal existence as a salesman for a cleaning supply company named Duskin, Ebisu created a series of short manga stories in the mid-1970s, selling to small but highly regarded markets like the legendary Garo. Somehow, he managed to develop a second, considerably more lucrative, career path as a leading television comic in Japan. Apparently, Ebisu is quite popular. He appeared in 22 different television shows in 1998, according to Holmberg. Snippets of his television comedy work are on YouTube. He has a charming clownish screen presence , with a goofy smile and a distinctive physical appearance. He is wealthy, according to Holmberg, but from his TV personality, not his singular and highly influential manga. It’s as if Mr. Bean was also a transgressive, seminal underground cartoonist.

But aside from the truth-is-stranger-than-fiction aspect of Ebisu’s adult life, one must consider the inescapable fact that his strange, incoherent, and unforgettable comics are a byproduct of growing up in the second, and (we all fiercely hope) last, city devastated by an atomic bomb. What incomprehensible abominations, what scenes of ruination and disfigurement, what profane absurdities did he observe as a boy? Perhaps the ominous-things-in-the-sky motif in the stories in The Pits of Hell originates with coming of age in a city destroyed by a bomb in the sky.

A Nagasaki survivor’s account of the aftermath of the bombing eerily resonates with the passage from Ebisu’s 1981 short story, “Salarymen in Hell” in which a negligent father is attacked by a human-faced bat that changes into a large lizard, a huge snake, and a human-sized centipede while trapped in an elevator plummeting down to Hell: “One survivor, Sadako Moriyama, had gone to a bomb shelter when the sirens sounded. After the bomb had gone off, she saw what she thought were two large lizards crawling into the shelter she was in, only to realize that they were human beings whose bodies had been shredded of their skin because of the bomb blast.” Perhaps the ominous-things-in-the-sky motif in the stories in The Pits of Hell originates with coming of age in a city destroyed by a bomb in the sky.

In his 2016 autobiography, No Gamble, No Life (as quoted by Holmberg), Ebisu declares his devotion to random chance: “I seriously want to ask people who don’t gamble, what happiness can you possibly get out of life?” While most likely a statement about the thrills Ebisu has experienced as a player, the statement also works as an artistic declaration. The stories in The Pits of Hell are gambles, each and every one. They refuse to hew to standard story logic with a beginning, middle, and end. Typically, they have two of the three but sometimes only a middle which circles in on itself like a snake eating its tail. Ebisu is gambling the reader will be able to fill in the missing pieces. This storytelling gamble, unlike some of Ebisu’s game wagers (reportedly), pays off the trifecta, royal flush, and jackpot all together.

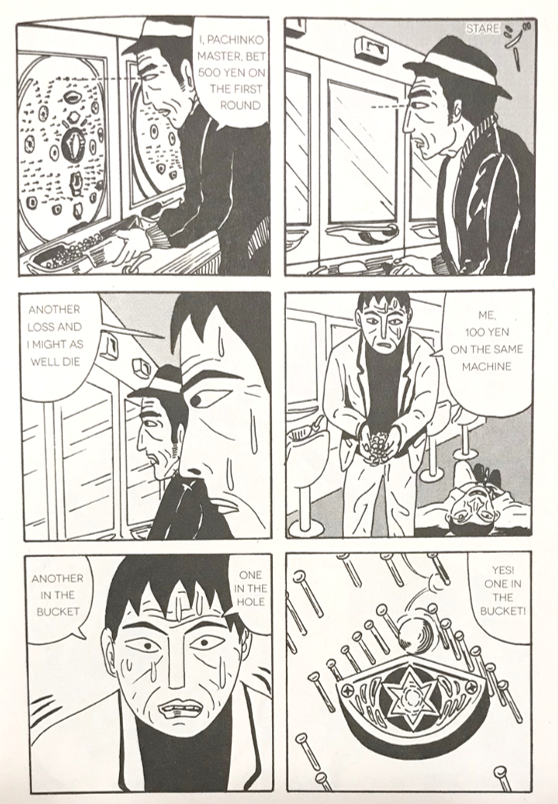

“Fuck Off,” an 18-page story in The Pits of Hell follows a man playing pachinko, a kind of vertical version of pinball played for prizes and tokens which can be traded to outside vendors for money. Here, Ebisu presents only a middle, in two parts. The first part of the story takes place in a pachinko parlor as a man bathed in sweat with eyes bugging out desperately hopes to win. It's life and death for him. We enter the scene as the action has started. There is no explanation given of who the man is or why he is so anxious to win. The intensity of this scene created within me the same coil of intense dread The Wages of Fear, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 film nightmare, generates.

The second part of the middle takes place in the man’s home as we learn he was playing to win food for his starving wife and two young children. The scene is as pitiful and pathetic as the poor family home scene with crippled Tiny Tim in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (another short-form masterpiece). Or, over here in Comicsland, as the Carl Barks story, “Christmas on Bear Mountain,” an homage to Dickens’s Christmas-themed short stories.

Ebisu’s family is so poor they are separated from their neighbors only by a paper wall. A sullen young man spies on the family through a small tear he has made, hoping, as Ebisu explains, “for bad things to happen to the family. He’s trying to get off on that … That’s why he has his dick out.” One gets the sense this scene is repeated every night.

The story is never resolved. What happens to the family when the winnings run out? Does the man somehow manage to keep winning? Does the neighbor ever get off? Is this Hell? Nothing is answered and yet the sad answers are felt deeply within: eventually the man will lose at pachinko and there will be no more food. Is he playing for his family, then, or himself and ransoming his family’s human needs to justify his addiction to the thrill of gambling?

Gulp.

This leads me to reflect on my own neglect due to my addictions of the Instagram, Facebook, and Internet varieties. Or, for that matter: writing. For years, I have poured my life energy into writing about comics and the returns have hardly put more than a few bowls of rice on the table – and yet… here I go again, trying to get my words to fit into the right slots. Get in the bucket. Get in!

I need something strong to distract me. Something like an Ebisu Yoshikazu manga story.