Sammy Harkham's warhorse anthology Kramers Ergot has by now spent over a decade as the foremost outlet for serious short form comics in the US. That's more than twice as long as its tenure as a scrappy, slightly zine-y venue for work by a promising contingent of very young cartoonists (issues 1-3, 2000-03), or the period it spent storming the gates with glorious, blasphemous redefinitions of the medium for the 21st century (4-6, '03-'06). If it isn't the mainstream, Kramers has still become a mainstream, with a definable impact, influence, and set of followers to call its own. There's fawning quotes from the New York Times and Time Magazine and more emblazoned on the newly released issue 10's belly band, proof of the publication's institutional status if you're the kind who needs it. Yet within a comics culture that initally struggled to deal with its mere existence, Kramers is often treated as a hot potato - too boundary-breaking or future-forecasting to be investigated as anything else.

Kramers Ergot 10 makes things plain as can be from its indicia on in, proclaiming debts in bright red capital letters to Raw, Weirdo, andThe Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics, a holy trinity of American anthologies. Weird shit in their time, in combination these titles laid out a rough playbook for the alt-comics style of the '80s and '90s - one that Kramers would provide a necessary pivot from a generation later. The name-drop opening of this volume suggests a circle closing, that focusing on differences between canon and challenger ignores their fundamental connection. "I felt like this issue could be the one where we make it explicit," Harkham told me in an Oakland alehouse on the eve of the book's release, "the relationship Kramers has always had to the history of comics. When issue 4 came out everyone was like 'oh, it feels so cutting edge and new, blah blah,' but the reason they're feeling that way is because it hearkens back to the last one hundred years of comics. There is a lineage that it's connected to. And in this one we just make that more explicit."

If Kramers isn't - never really has been - the all-destroying comet from an imagined avant-garde many wanted it to be during its mid-oughts period of greatest notoriety, what can it be? For me, this issue suggests itself as a more ideal version of the eternally benighted Best American Comics series: an anthology showcasing new work by a collection of proven talents, both long established and still ascending, with an elevated level of quality as its lone polestar. "In comics there's no reason to do anything that doesn't put quality as its number 1 priority," Harkham opines. "You can't say that about any other medium, pretty much - people are trying to get things done on deadlines or fill a slot on Netflix or whatever. But with this the goal is to make the book as good as you can. It connects to this idea of comics as a whole. With an anthology you're not focused on this book or this artist. You're saying I like this medium. I like all of it, you know?"

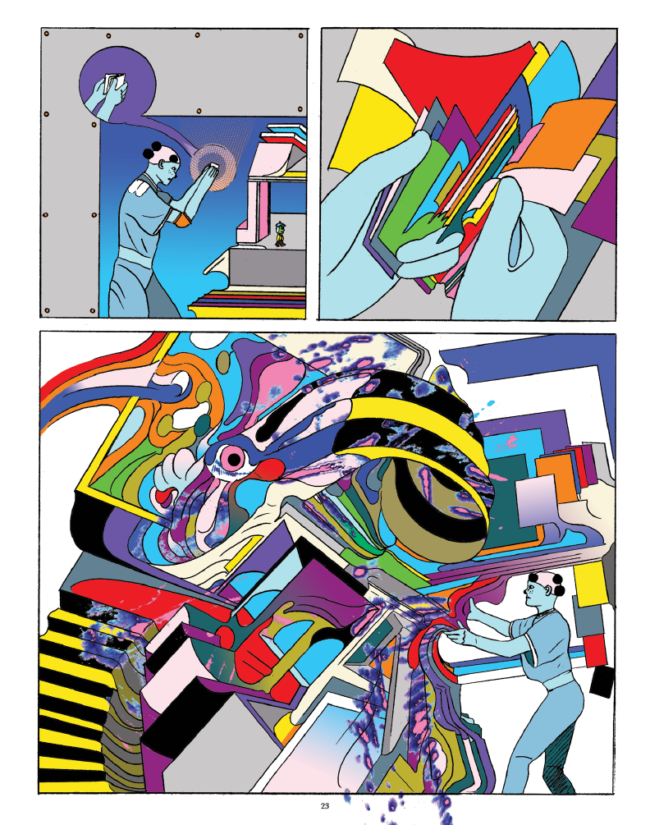

Indeed, more than any previous issue, this Kramers has something for anyone who's into comics, if the rep it's been assigned doesn’t circumscribe who'll pick it up. One-page gags by a history of greats from Frank King to Simon Hanselmann orbit longer pieces by Connor Willumsen or Harkham himself that demand equal weight be given to both ends of the old “literary comics" descriptor, with squint inducing formalism from C.F. and Marc Bell forcing readers to confront work that reads like nothing else, and Lale Westvind throwing red meat to the peanut gallery with a body horror comic rooted firmly in the Golden Age superhero idiom. The book sees talented artists like Aisha Franz, John Pham, and Will Sweeney making comics that don't really invite comparison to any others, but fit perfectly in a collection bound together more by the high level its contributors are working at than any stylistic tendencies.

Indeed, more than any previous issue, this Kramers has something for anyone who's into comics, if the rep it's been assigned doesn’t circumscribe who'll pick it up. One-page gags by a history of greats from Frank King to Simon Hanselmann orbit longer pieces by Connor Willumsen or Harkham himself that demand equal weight be given to both ends of the old “literary comics" descriptor, with squint inducing formalism from C.F. and Marc Bell forcing readers to confront work that reads like nothing else, and Lale Westvind throwing red meat to the peanut gallery with a body horror comic rooted firmly in the Golden Age superhero idiom. The book sees talented artists like Aisha Franz, John Pham, and Will Sweeney making comics that don't really invite comparison to any others, but fit perfectly in a collection bound together more by the high level its contributors are working at than any stylistic tendencies.

Still, Harkham dismisses the Best American Comics comparison. "Best American has to serve this sort of phantom audience. What regular people want, or what librarians want. More squares are reading comics, but I don't care about squares or the comics they're reading. There's never been a drive towards cheerleading for comics - people should come to us. We don't need to go to them." An audience for the book is presumed, with no conversions necessary... even if it won't be banging down the doors en masse on new release Wednesday. "Let's just make a great book for the people who are gonna find it in a library, find it ten years from now, find it on a friend's couch, a dorm room," Harkham says casually. "That audience base is fucking rad. I love that audience."

Speaking as a longtime member of its captive audience, Kramers 10 is a great issue, to my mind the best since 2006's issue 6. It's the largest one since the hot take-generating $125 broadsheet-sized issue 7, but its handfeel is pleasingly insubstantial, a nice floppy comic book whose cover's gold foil framing might almost have gotten there by accident. "We wanted something very light that you could read on the toilet or in bed," Harkham says. "Like a big oversized annual. I've been reading Wonder Woman treasury editions with my daughter, and the art's amazing, the stories are great, the size is great, the interior paper isn't super heavy and glossy... it's a great reading size and a great looking size. It's definitely exactly Raw #7 size. That was a comic that I got out of a one dollar bin and is still an evergreen for me." You could say this is an editor trying to have his cake and eat it too, thumbing his nose at his book's status as a subcultural touchstone while further cementing it, but maybe it’s also just what these things are at their core - there’s probably not too many pristine copies of Raw and Weirdo floating around these days, and Kramers 10's production proclaims that it's okay with being similarly destined to degrade.

This is the shortest issue in a long time too, with only a few pieces that demand focus for more than a few minutes. Where earlier issues' sprawl was a huge part of their appeal, slopping one ladleful after another of stuff onto the reader until a state of total passive reception was inevitably reached, there's a pleasing crispness to this issue - maybe the very first one you can read right through without feeling like it's inevitable that you'll be missing something. It's also the first issue in well over a decade not to feature any non-comics illustrations. "You don't want 300 pages of that size," the editor says, "and there was no reason to run just a drawing by someone. As you get stuff in it makes other work unnecessary."

Harkham practices with the concision he preaches. His own story, titled "Blood of the Virgin" like his current solo book in progress, is as ruthlessly edited as any Hemingway, with a cowhand-turned-early film director's winding life in the entertainment industry summed up in 24 elliptical pages that beg for the adjective "whirlwind". For the first time since his instant classic "Poor Sailor" in Kramers' breakthrough issue 4, Harkham's contribution forms the spine of an issue. "It makes me look like a fucking asshole," he mutters. "I was very insecure about it. I don't love the idea of being the editor and the guy with the longest story." But it serves a purpose: "My work is very narrative, it's very grounded, so just by knowing that it's gonna be in the book that gives us room. It lets us do something more visual, because you know that mine is gonna be so grindingly literal." Harkham hits something real here - there is a sense of level footing in this issue of Kramers that past volumes haven't had. Somewhere a half-empty glass is mouthing that the insurgent-turned-incumbent magazine has lost a certain anarchic spirit as it hits double digits. But this is also what it looks like when a publication that's long championed a medium cleaves more closely to it. Previous Kramers have felt as much like exhibition catalogs or art books as anything else, but this one is a comic full of comics, more a comfort for readers than a challenge.

Harkham practices with the concision he preaches. His own story, titled "Blood of the Virgin" like his current solo book in progress, is as ruthlessly edited as any Hemingway, with a cowhand-turned-early film director's winding life in the entertainment industry summed up in 24 elliptical pages that beg for the adjective "whirlwind". For the first time since his instant classic "Poor Sailor" in Kramers' breakthrough issue 4, Harkham's contribution forms the spine of an issue. "It makes me look like a fucking asshole," he mutters. "I was very insecure about it. I don't love the idea of being the editor and the guy with the longest story." But it serves a purpose: "My work is very narrative, it's very grounded, so just by knowing that it's gonna be in the book that gives us room. It lets us do something more visual, because you know that mine is gonna be so grindingly literal." Harkham hits something real here - there is a sense of level footing in this issue of Kramers that past volumes haven't had. Somewhere a half-empty glass is mouthing that the insurgent-turned-incumbent magazine has lost a certain anarchic spirit as it hits double digits. But this is also what it looks like when a publication that's long championed a medium cleaves more closely to it. Previous Kramers have felt as much like exhibition catalogs or art books as anything else, but this one is a comic full of comics, more a comfort for readers than a challenge.

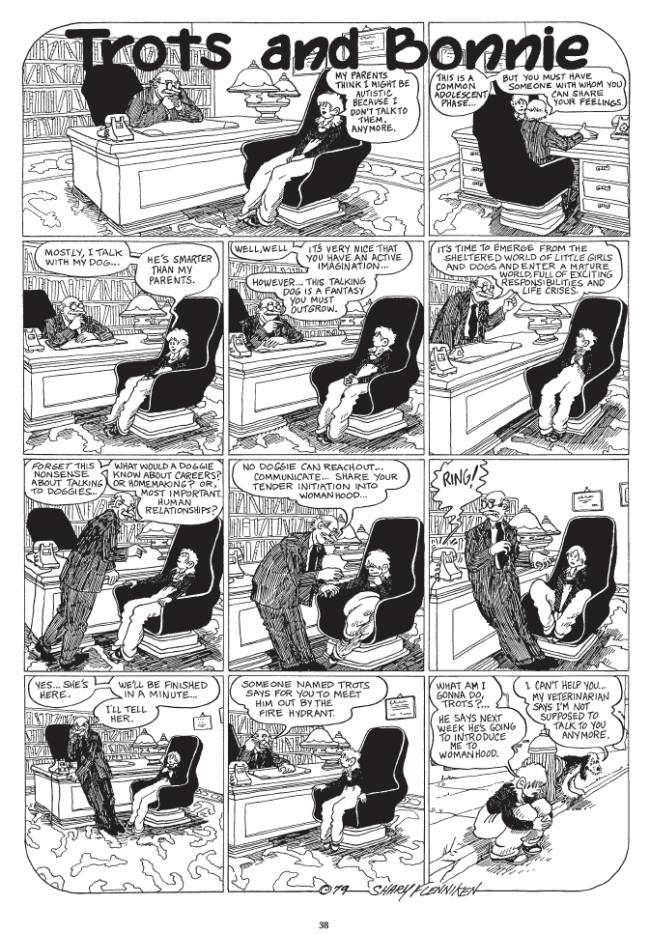

It's also a comic full of reprints, or at least work that wasn't originally created for publication here. Though rarely discussed as a venue for reprinted works, Kramers has produced some highlights in its time, introducing the English-speaking world to Suiho Tagawa and Marc Smeets in issue 6 and infamously closing its 8th volume with enough episodes of Penthouse's airbrushed sleazefest "Oh, Wicked Wanda" to choke a horse. The big ticket in issue 10 is clearly the section devoted to Shary Flenniken's Trots and Bonnie, a one-page gag strip about a tween girl and her talking dog that ran in National Lampoon from 1972-90, pasting Brady Bunchian cheer over an almost unbearable parade of misogynistic, patriarchal abuses. Flenniken's comics couldn't be better suited to right this second; that this stuff was ripe for reprinting is self-evident. That it's Kramers doing it is both surprising and obvious.

The book's scattering of other reprints is lower-key, but still impactful. A Robert Crumb two-pager looks incredible, gives Kramers another marquee name on its contributor list, and exhumes a piece of that guy's work that points its spleen at a fully deserving target (namely “those right-wing party dudes with too much testosterone and not enough money" who've managed to take over this country's political apparatus since Crumb laid these panels down in 1990). A single translated page from French virtuoso Blutch's "covers album" Variations is stunning to behold and provides a steadying hit of straight genre comics amid stranger surroundings, its re-rendering of a classic page from Moebius's Blueberry series inviting us to look at another all-time great through this book's oddball filter. A typically whimsical Gasoline Alley Sunday page from 1922 slots in seamlessly among more pointed stories. "Frank King is making work in a completely different context," Harkham expounds, "but there is a connection. He's bringing energy and a personality to work for hire that he's not being forced to. And I also like thinking of this book as not existing out of thin air. There's a river of comics history, and I'm just throwing in, you know?"

The book's scattering of other reprints is lower-key, but still impactful. A Robert Crumb two-pager looks incredible, gives Kramers another marquee name on its contributor list, and exhumes a piece of that guy's work that points its spleen at a fully deserving target (namely “those right-wing party dudes with too much testosterone and not enough money" who've managed to take over this country's political apparatus since Crumb laid these panels down in 1990). A single translated page from French virtuoso Blutch's "covers album" Variations is stunning to behold and provides a steadying hit of straight genre comics amid stranger surroundings, its re-rendering of a classic page from Moebius's Blueberry series inviting us to look at another all-time great through this book's oddball filter. A typically whimsical Gasoline Alley Sunday page from 1922 slots in seamlessly among more pointed stories. "Frank King is making work in a completely different context," Harkham expounds, "but there is a connection. He's bringing energy and a personality to work for hire that he's not being forced to. And I also like thinking of this book as not existing out of thin air. There's a river of comics history, and I'm just throwing in, you know?"

The book's final reprint is a two-page Spain Rodriguez/Kim Deitch collaboration that originally ran in a 1968 issue of the East Village Other, and appears here framed by a new Deitch buddy-comedy comic relating its process of creation. It points up how often the river of comics history Harkham mentions has wound through terrain that isn't taken up by comic books as such. The East Village Other; National Lampoon; the King page is a tearsheet from the Chicago Tribune. In a long autobiographical text from Jaime Hernandez on Kramers 10's indicia page, the Love and Rockets Hall of Famer reminisces: "We were always drawn to comics. If there was something in a magazine and they had an ad that was drawn like a comic, we were always drawn to that." In making his case for the form and its lineage in this book, Harkham reminds us that it's never been holistic. "Without a doubt, comics have only built audiences by sneakily getting into people's way," he claims. "In newspapers, in magazines - that's always been how regular people have had a relationship with comics. If anything, what we've been dealing with for the last 20 years is going more like 'no, comics are something you should search out'. All I know is the audience has always been a certain percentage of the populace, and I'd say that percentage has stayed the same for the last 40 years."

Other concerns are more apparent, though Harkham insists that as an editor he "never think(s) thematically, only visually". Beginning with Jaime conjuring the bedroom-bound fraternal comics obsession of his childhood, the book treats of its medium as something hermetic, a coded language that exists all around us but can only be truly understood by a small group of seekers. David Collier's one-pager recalls a youth spent in libraries diligently uncovering the history of his chosen medium, and muses on pioneering comics critic Coulton Waugh's traveling the same well-trod ground. Comics by Helge Reumann and Jason Murphy veer toward abstraction, but retain just enough connective tissue to tease readers into believing that looking just that little bit harder might make their pieces fit together neatly. Ron Rege's page aims for the heart of the thing, illuminating a section of an alchemical text by 17th-century astronomer Johannes Fabricius.

Other concerns are more apparent, though Harkham insists that as an editor he "never think(s) thematically, only visually". Beginning with Jaime conjuring the bedroom-bound fraternal comics obsession of his childhood, the book treats of its medium as something hermetic, a coded language that exists all around us but can only be truly understood by a small group of seekers. David Collier's one-pager recalls a youth spent in libraries diligently uncovering the history of his chosen medium, and muses on pioneering comics critic Coulton Waugh's traveling the same well-trod ground. Comics by Helge Reumann and Jason Murphy veer toward abstraction, but retain just enough connective tissue to tease readers into believing that looking just that little bit harder might make their pieces fit together neatly. Ron Rege's page aims for the heart of the thing, illuminating a section of an alchemical text by 17th-century astronomer Johannes Fabricius.

A more prominent theme is the shadow of economic exploitation, which hangs over a majority of the book's longer stories. Harkham's slice of fictional biography chronicles one man's struggle to free himself from the degrading machinery of early Hollywood. Anna Haifisch transmutes Mervyn Peake's short story "Rottcodd and the Hall of the Bright Carvings" into a pointed fable about artists' exploitation by capital, one that finds a harmonious counterpoint here in Aisha Franz's tale of the super-rich. The most chilling of Flenniken's Trots and Bonnie strips sees a middle-aged man extracting sexual acts from uncomprehending young girls by buying their Girl Scout cookies, and twists the knife with the suggestion that Avon saleswomanship lies in their future. Connor Willumsen, John Pham, and Will Sweeney all train eyes on the struggles of the ordinary working stiffs who drive your cabs, make your smoothies, and pack your fucking Amazon boxes.

"I hadn't put it together in that way," Harkham says, "but it's all in the book. It's pretty clear what my instincts are, what I'm thinking. You start sensing themes and connecting tissue between stories. Everything around (the book) is connecting to this larger picture of like, it doesn't make sense to make comics, and it's not a medium that rewards you as a maker. It doesn't even reward you as a reader very often! Most of my friends who read comics follow like half a dozen cartoonists who never publish. It's like one thing every couple years, and every day they wanna read about comics and think about comics - but there's nothing out there. It's very dire. When I think of what comics needs, it's something of high quality that comes out regularly and can pay well. That would be amazing! And since Kramers fails at both we'll just keep holding out."

Unprompted, Harkham changes subjects as our talk nears its end. "All the energy most people spend online, I spend making anthologies," he muses. "Maybe that energy would be better spent making solo books with other people where I work as an editor. There's a lot of great comics that are out of print, there's a lot of great artists who are not being advocated for. With Kramers you're at the whim of the quality of the work that you get in, whereas if I look at an artist who did great work and it's all out of print - that exists. I did this one thinking this might be our last issue."

I say he's making me wanna cry, then offer that during the four year layoff and change of publisher between issues 7 and 8 I'd assumed we'd already seen the final Kramers - and that was a decade ago now. Harkham laughs. "I would never put quotes on a belly band on the front cover unless I was like, you know what? Fuck it. Let's remind everyone... these books did alright."

He pauses before continuing. "But that all said, if Tim Hensley was like 'hey, I got this 24 page story and I don't know what to do with it'? Yeah, very quickly we would be working on Kramers 11. If Julie Doucet was like 'oh, I never reprinted this thing, we should do something'? There'll be a Kramers 11."

I ask Harkham why he led the book off with a massive blockquote of the fourth Hernandez brother's childhood drawing-table remembrances. He relates a long, fruitless search for some piece of intense writing about some specific comic which could serve as a tone-setting introduction for the book, before his frequent dinner companion Jaime dropped something ideal in his lap, “suggesting that there's nothing but making comics, and that there's no choice but comics, and that all the reward is in comics."

Kramers 10's table of contents is printed on its final page. An epigraph above it displays an old Yiddish saying: "For a little love, you pay a lifetime."