Neal Adams, whose vigorous, realistic, emotional art arguably set the highest standards of the Silver Age comics mainstream, died April 28 at the age of 80 of complications from sepsis. Only Jack Kirby could be said to be more influential on comics artists of the day, but whereas Kirby gave expressive shape to the most fantastic visions of the superhero genre, Adams’ heroes seemed to live in the same world we lived in. His images combined a detailed realism with an exhilarating dynamism, so that one could almost imagine meeting Batman on the street or squinting up at the stars to see the Avengers mixing it up with alien armadas. As much as Adams was admired for his art, he was also known and respected as a fighter for creators’ rights who helped form the Academy of Comic Book Arts and spearheaded one of the first serious efforts at a union for comics creators.

Neal Adams was born June 15, 1941, in Governors Island, New York, a self-described Army brat living in various areas of the East Coast United States and, for a time, Germany. In a recent Front Row Center interview conducted by Howard Chaykin on the NeoText website, Adams said he grew up reading comic strips as well as Golden Age comic books starring Captain Marvel and Blackhawk, while enjoying early television shows including Hopalong Cassidy and Captain Video. His hands were both restless and talented as he found himself able to draw figures that evaded the skill of his fellow classmates, including big-foot characters like Atomic Mouse and superheroes like Batman. Sensing an immense talent, Adams’ mother enrolled him in the High School of Art and Design, which was initially named the School of Industrial Art. It was founded in 1936 and functioned as a vocational high school. To be accepted, potential students had to apply through an exam and portfolio. Once in, they would have to sample all subjects during their freshman year before selecting what their major would be for the next three years. Its alumni included such comics and animation veterans as Al Plastino, Chic Stone, Carmine Infantino, Alex Toth, John Romita, Ralph Bakshi, and, in 1959, Neal Adams.

After graduation, Adams was eager to gauge his skills professionally at DC Comics but was turned away. Despite his talent, the DC editors were very territorial and older artists already occupied the company’s busy production schedule. His first published comic book panel would instead be published by Archie Comics in Adventures of the Fly #4 (Jan. 1960). As Adams mentioned in a 2018 interview for the Comic Book Historians podcast conducted by Alex Grand and Bill Field, the title's editor at Archie preferred a panel Adams had drawn of Tommy Troy transforming into the title superhero over Jack Kirby’s, so he cut it out from a page submitted by Adams and paid him for only 1/3 of the page. Despite not being picked up for the full feature, Adams' skill was noticed while working on other, smaller humor assignments, and he was soon recommended by an associate to Howard Nostrand, who was working on the Bat Masterson newspaper strip.

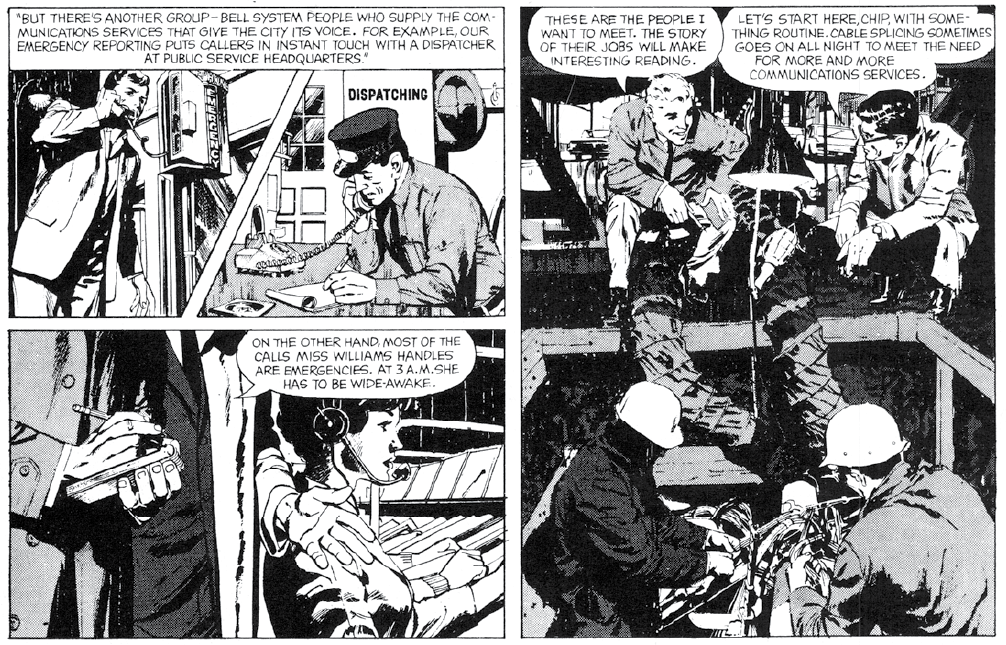

Nostrand had teamed up with Elmer Wexler to set up a new studio and, through that studio, hired Adams as an assistant to work on Bat Masterson. Adams credited Wexler with instilling in him the work ethic that kept him drawing all his life, and it was also through Wexler’s supervision and recommendation that Adams found work at the Johnstone and Cushing advertising agency, where he created advertisement comics for corporate clients such as General Electric and the Bell Phone Company. His storytelling skill was evident, and he was soon asked to draw the Ben Casey comic strip, a daily and Sunday serial newspaper strip based on the television show, from 1962 to 1966. Hungry for work, Adams also was a ghost artist for other comic strips, including The Heart of Juliet Jones and Peter Scratch.

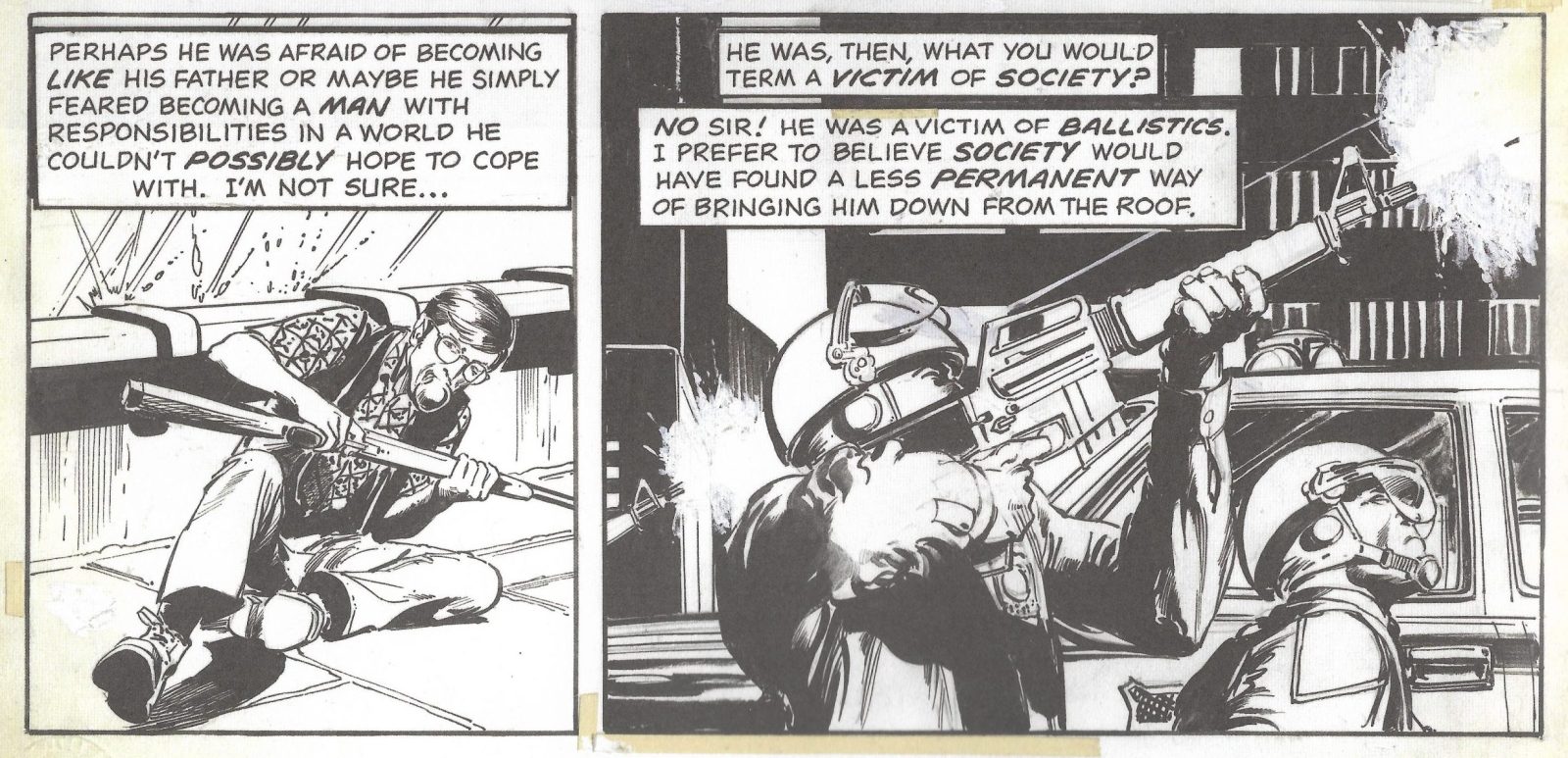

The result was that, when he returned to comic books, Adams brought with him a skill for rendering psychological drama that was unusual for superhero comics. Initially, his approach was a natural fit with editor Archie Goodwin at Warren, and he demonstrated a profound visual storytelling ability in both Creepy and Eerie magazines starting in 1967, with characters strolling through highly-detailed cityscapes and wearing the modern fashion of the day.

Meanwhile, DC Comics was still fairly shut off from new artists, but there were signs of change, including the promotion of artist Carmine Infantino to editorial director in 1966. His advancement signified that publishers Irwin Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz were ready to see the creative direction of the company steer toward illustration and dynamic visual design, rather than the previous paradigm overseen by retired pulp magazine editors. Adams’ first titles there were The Spectre, Strange Adventures and Our Army at War. Adams took over the art on the unusually noirish and gritty "Deadman" series in Strange Adventures #206-#216 (Nov. 1967 to Jan./Feb. 1969) from Infantino. Working under editors Jack Miller and Dick Giordano, Adams' work on the series is well-remembered by comics enthusiasts for its bold, mind-bending layouts, including one panel that celebrated a creative contemporary at Marvel with abstract letters proclaiming “A Jim Steranko Effect.”

Comics pro Joe Kubert became less available at DC Comics since he had taken on penciling art duties on the Robin Moore newspaper strip, Tales of the Green Berets, which left a vacancy for Adams’ entry to Our Army at War #182 (July 1967) under editor Bob Kanigher. It was a Karmic opportunity, since Adams had helped Kubert get the Green Berets job. Adams' realistic approach to comic art became immediately noticed by fans as something which was not just new, but also rare. Other editors such as Murray Boltinoff offered Adams more work, including The Adventures of Jerry Lewis and The Adventures of Bob Hope. Editor Mort Weisinger eventually gave him cover duties such as Action Comics #356 and Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane #79, both in 1967. Editor George Kashdan followed suit, and Adams finally drew Batman for the cover of The Brave and the Bold #76, with Weisinger assigning him the cover and interiors to World’s Finest Comics #175 in 1968.

In all instances, Adams amazed readers with his ability to render superheroes using stylized realism in fantastic settings. In 1969, while at DC Comics, Adams also supplied penciled pages for Marvel Comics in The X-Men #56 to #63, written by Roy Thomas. He grabbed readers’ attention for a series on the brink of cancellation using panel-bursting experimental layouts. Some memorable depictions during these issues are his illustrations of the Living Pharoah in Egypt as well as Sauron and the Savage Land, which evoked a visual magic akin to J. Allen St. John’s cover to At the Earth’s Core (1922). During his time on the series, Adams was inked by Tom Palmer, whose style was sensitive to realistic, cinematic detail and who was also inspired by newspaper strips.

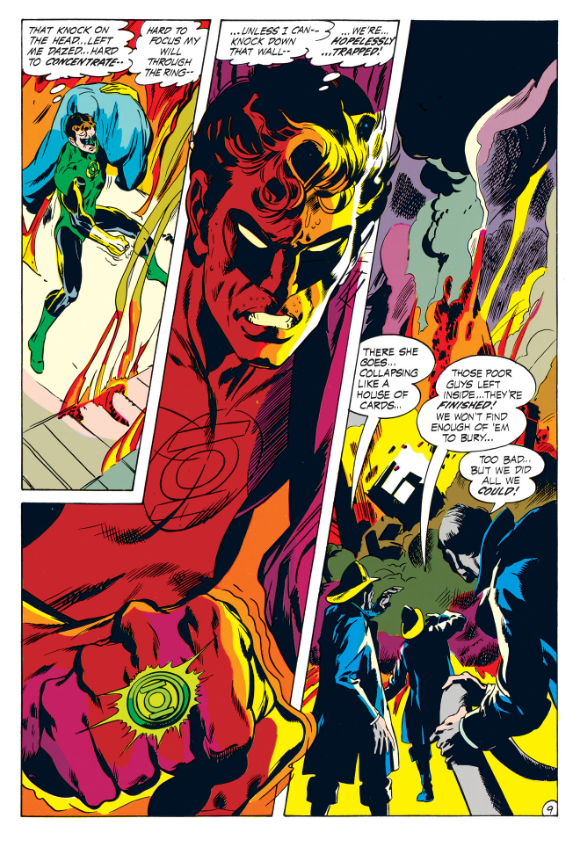

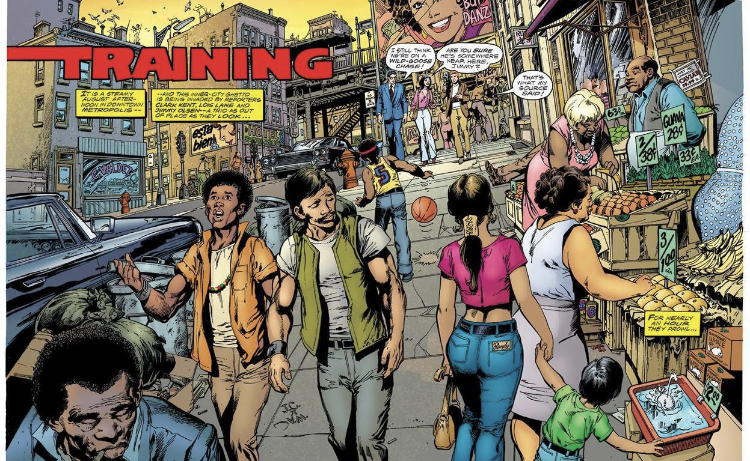

Their last X-Men issue together, #65, coincided with the beginning of Adams’ long collaboration with writer Dennis O’Neil. Under Julius Schwartz at DC Comics, they began their "Green Lantern/Green Arrow" run with the thematically groundbreaking Green Lantern #76 (April 1970), continuing through #89 (April/May 1972), focusing on social realism with topics such as racial and economic inequality. The two titular characters debated politics, law enforcement and poverty on a literal road trip through American social problems. Adams and O’Neil also revitalized Batman, returning the hero to his dark roots, and, in issue #232 (June 1971), co-creating the recurring villain Ra's al Ghul.

Adams’ facility with cinematic storytelling played a strong role in his depiction of the Kree-Skrull War in The Avengers #93–96 (Nov. 1971-Feb. 1972) with writer Roy Thomas, including a memorable sequence of Ant Man’s exploration of the Vision’s internal organs. Also in 1971, Adams illustrated both the playbill and the poster for Warp!, a science-fiction play scripted by Lenny Kleinfeld. Many regard this era as a very creatively fertile period for Adams.

Historians and fellow comics professionals credit Adams for also opening DC’s doors to other similarly-minded illustrators, including Bernie Wrightson, Howard Chaykin and Michael Kaluta, among others, who appeared to shift the house style from the clean, stiff cartoonishness of Wayne Boring or Curt Swan to more of a stylized realism.

As Adams paved the way for the next generation of comic book artists, he also tried to utilize his success to raise the standard of living for his fellow illustrators. In 1969, Adams, Infantino and Stan Lee helped found the Academy of Comic Book Arts, which Adams viewed as an organization that could champion creator rights, demand royalties, improve pay, and guarantee original art returns. The organization quickly split into those who wanted to focus on creators’ working conditions, and those who, like Lee and Infantino, would rather it serve a promotional function similar to that of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. This division was reflected in its administrative offices, the position of president first occupied by Lee, and later by Adams. Rather than support Adams’ unionizing goals, Lee and Infantino later departed the organization. Quoted by Jon Cooke in Comic Book Artist #16, writer Jeff Rovin said, “I can't tell you how many times [Marvel Publisher] Martin [Goodman] would listen to some of the things Neal Adams was saying and mutter, ‘Who the hell does he think he is?’” Adams became the organization’s lead figure, but it failed to unionize comic book creators, and although there were regular meetings, newsletters, and ceremonies for its Shazam Award, it eventually ended in 1977. Instead, writers and artists attended Adams’ social First Friday gatherings.

Adams’ sense of disappointment in the corporate structure at DC and Marvel Comics may have prompted him to start Continuity Associates with Dick Giordano in 1971. CA packaged comics and magazines with the help of a variety of new or upcoming artists and writers. Their team also provided advertising services, as well as motion picture storyboards. During this period, Adams influenced future comics artists and writers including Carl Potts, Trevor Von Eeden and Larry Hama, among others. On the Comic Book Historians podcast in 2019, Marvel alumni Hama and Potts separately described Adams’ presence at Continuity as both paternal and critical. Potts said Adams initially made it clear that his early work was “not even worth commenting on,” and turned around to walk away. “And I don’t know how I worked up the nerve,” Potts remarked, “but I just said, ‘Well could you at least tell me what to work on?’ So he turned around and he proceeded to name every aspect of drawing and composition and storytelling, and you know, layout, everything, and anatomy, everything.” Hama described nervously sitting close to Adams at Continuity with the patriarch looking over his shoulder, while being taught to slowly push past his comfort zone to pencil increasingly difficult poses.

It was perhaps this paternal approach to other artists and the security of successful self-employment that positioned Adams to challenge DC Comics to provide Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster credit and pay for creating Superman. He used his own funds to pay for Siegel’s and Shuster’s legal representation by Ed Preiss, father of publisher, Byron Preiss, and after a three- to four-month public-relations campaign, Adams and Jerry Robinson helped secured the Superman creators their byline and pension in 1976. In a public response to a 1976 copyright law that took effect in 1978, Adams advised comic book artists at Marvel: “You MUST NOT be referred to in any contract or work order as ‘work for hire.’ Burn it into your brain! You are a FREELANCER! An author!” Many struggling artists, however, were too eager to work to heed his advice.

In 1978, Adams again tried to encourage comics creators to organize by supporting the formation of the Comic Book Creators Guild. At the Guild’s first ad hoc committee meeting, Adams delivered a passionate speech: “We don’t have workman’s compensation. We’re lower than anybody! We have nothing! We have the rate we can get. When we’re sick, we don’t get money because we’re freelancers and we don’t have a job. We don’t have a retirement fund. And we’re paid according to 1958 standards.... At some point we have to stop worrying about whether the company can pay us. Let’s go in, make our demands, talk back and forth, compromise. If they say they can’t afford it, have them bring out their books and show us how they can’t afford it; let’s see their profit and loss statements. It is not our job to raise the price of comic books. It is our job to watch out for us, to protect us and to take care of us. And we’re not doing it well.” The Guild supported Mike Ploog and Jack Kirby in their refusal to sign new Marvel contracts and identified a number of goals for creators, but by 1980 it had succumbed to a tightening market for comics work and never obtained wide membership.

Advertising provided Adams with financial security at Continuity, and he began to cut back on his own comics work. But he did find time to pencil and write Superman vs. Muhammad Ali (1978) with plotter Dennis O’Neil under publisher Jenette Kahn. The memorable cover with identifiable celebrities in the audience had a design that portrayed both heroes with strength and respect. In 1980, he directed and wrote a film starring his children, Jason and Zeea - initially called Nannaz, it was later retitled by Troma Entertainment as Death to the Pee Wee Squad. In the early 1980s, he dabbled in some occasional comics jobs, such as a story in the Marvel magazine Bizarre Adventures #28 in 1981, and his creator-owned Ms. Mystic, which was published independently through Pacific Comics in 1982. Continuity formed its own comics line in 1984, publishing a variety of titles such as Revengers featuring Megalith, Samuree and Bucky O’Hare, often with cover art and story concepts by Adams. Thirteen episodes of a Bucky O'Hare and the Toad Wars! TV show were produced, with Adams acting as executive producer, art designer and associate story consultant (which included writing one episode). After 10 years, Continuity Comics went defunct in 1994, and some of those characters were later published through Windjammer, a creator-owned line at Acclaim Comics.

Other TV and movie credits collected by Adams included conceptual and design art for Stuart Gordon’s horror cult films From Beyond (1986) and Dolls (1987), the sci-fi movie Circuitry Man (1990) and character design for Ted Turner’s Captain Planet and the Planeteers (1990).

In the later 1990s and 2000s, Adams sometimes took on an art job or a cover here and there for Marvel and DC, but ultimately, advertising remained his bread and butter. On the Comic Book Historians podcast, he mentioned the Nasonex Bee, a commercial mascot for the nasal spray Nasonex which had the voice of Antonio Banderas and paid his firm “a few million dollars.” He returned to comics occasionally in the 2010s for projects such as Batman: Odyssey, The New Avengers, The First X-Men, Superman: The Coming of the Supermen, and a new Deadman series. He also made some appearances at comic conventions, accepted commissions, and was generally available to fans and historians for interviews.

For the past couple of decades, Adams had become absorbed by a geological theory that the Earth is growing larger. He posted several science videos explaining the theory on his Continuity Studios website and said he had devoted himself to a 200-page graphic novel on the subject, which has not been published.

In June 2021, Adams disclosed on his Facebook page that he suffered a near-death experience with sepsis that hospitalized him and temporarily placed him on dialysis. The event “cost him 40 pounds and half his muscle tone” and appeared to have physically damaged him. Sepsis, in which the body responds so severely to an infection that it attacks its own organs, has a high fatality rate, and although he appeared to make a strong recovery last year, complications from the disease eventually took his life.

Announcement of his death brought an outpouring of grief on social media from fans and colleagues:

Alex Ross: “One of the greatest artists in the history of American illustration has passed away. Neal Adams was a seismic influence on how one depicts life. His dynamic interpretation of realism combined with the energy shaped generations of artists. People like me wouldn’t be here without him.”

Jim Lee: “When I was a kid, I idolized the work of Neal Adams. His artistry brought the world of superheroes to life with a sense of realism and dynamism that I had NEVER seen before.”

Bill Sienkiewicz: “My artistic father #nealadams has passed. No words.”

J.M. DeMatteis: (referring to the game-changing Green Lantern #76): “Adams' work with Denny O'Neil on Batman helped redefine the character, but THIS is the book that really impacted me, back in the day.”

Neil Gaiman: “Neal Adams is gone. He was the reason I drew Batman in every school exercise book. He reinvented the look of comics pages and characters, made me care about comics at the point where I didn’t care any more, and I wish I’d been lucky enough to write a story he drew.”

Andrew Farago: “When celebrating Neal Adams as an artist, remember to celebrate him as a tireless advocate for creators' rights, too.”

The global comics community had long paid its respects to Adams with honors and awards, including four Alley Awards (1967, 1968, 1969 twice), four Shazam Awards (1970 & 1971, twice each), an Inkpot Award (1976), two Comic Fan Art Awards (aka Goethe Awards, both 1971), a Spain-based Haxtur Award (1999), a Hero Initiative Lifetime Achievement Award (2009) and a Sweden-based Adamson Award (2018). He was also inducted into the Eisner Awards Hall of Fame (1998) and the Joe Sinnott Hall of Fame (2019).

His lifelong youthful appearance made it hard to imagine him turning 80, but in more than one sense, Adams helped mainstream comics to grow up a little. He pushed creators to rebel against the parental control of corporate publishers. And he reminded an industry that had been infantilized by the Comics Code Authority that it could tell consequential stories with realistic figures. His illustrations depicted heroes with a stylized realism that elevated the impact of comic books. He proved to a cynical industry of the 1960s that superheroes could be as real as the person next to us, and their struggles and challenges could reflect issues that were to be taken seriously. His art contained depths of human drama and superhuman energies. Whether it was Angel soaring next to Egyptian ruins or the Inhumans crawling out of the sea, he provided viewers with an impossible movie on paper. He knew he was good, better than most, but he looked out for other creators whether they were older or younger. Through the course of his life, he was the big dog who looked out for the underdog.

Posting on Twitter, Adams’ son Josh Adams wrote, “Neal Adams' most undeniable quality was the one that I had known about him my entire life: he was a father. Not just my father, but a father to all that would get to know him."

Adams is survived by his wife, Marilyn, and sons, Jason, Josh and Joel, daughters Zeea and Kris, and grandchildren Kortney, Jade, Jane, Jaelyn and Sebastian and his great-grandson, Maximus.