From The Comics Journal #104 (January 1986)

Many of us seem reluctant to declare underground comix dead. Just as many of us are unable to view that death as a natural one. Asking, “What happened to underground comix?” is like asking, “Why isn’t anyone dancing the Charleston anymore?”

It’s over. Gone the way of newsreels, black & white television, patriotism, and Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man. Underground comix died with love beads and long hair (as a statement) and flower children and that whole psychedelic era. A few titles continue to appear sporadically from Last Gasp, Kitchen Sink, and Rip Off Press supposed sure-sellers such as Dope Comix, Bizarre Sex, and the despicable Cocaine Comix. All the aforementioned, however, seem to exist and survive as mere ghosts of a once-exciting and thriving subgenre of comix, comix that were authentic ingredients and byproducts of a genuine American youth movement. Only Leonard Rifas’s Educomics and Howard Cruse’s Gay Comix can claim social relevance today. The last underground I bought was Bizarre Sex #9, and that was only because I had read so much about Reed Waller’s Omaha, the Cat Dancer; the art was certainly competent and the story was compelling enough, an unquestionable change of pace, but overall, it was just a funny animal porno comic. Otherwise, it has been years, literally, since I bought an underground, the last one probably, being Moondog #4, or one of Jaxon’s Indian history comix. It never occurred to me to buy the last couple issues of Zap simply for the sake of completion.

It could be said that titles like Slow Death and Skull and Death Rattle later became comics like Twisted Tales and Alien Worlds and magazines like 1994 and Heavy Metal. Privately published comix such as Dr. Wirtham’s Comix & Stories and American Splendor continue to appear, but this is more a commitment of their publishers / editors than a bona fide business venture: despite the need to break even on expenses.

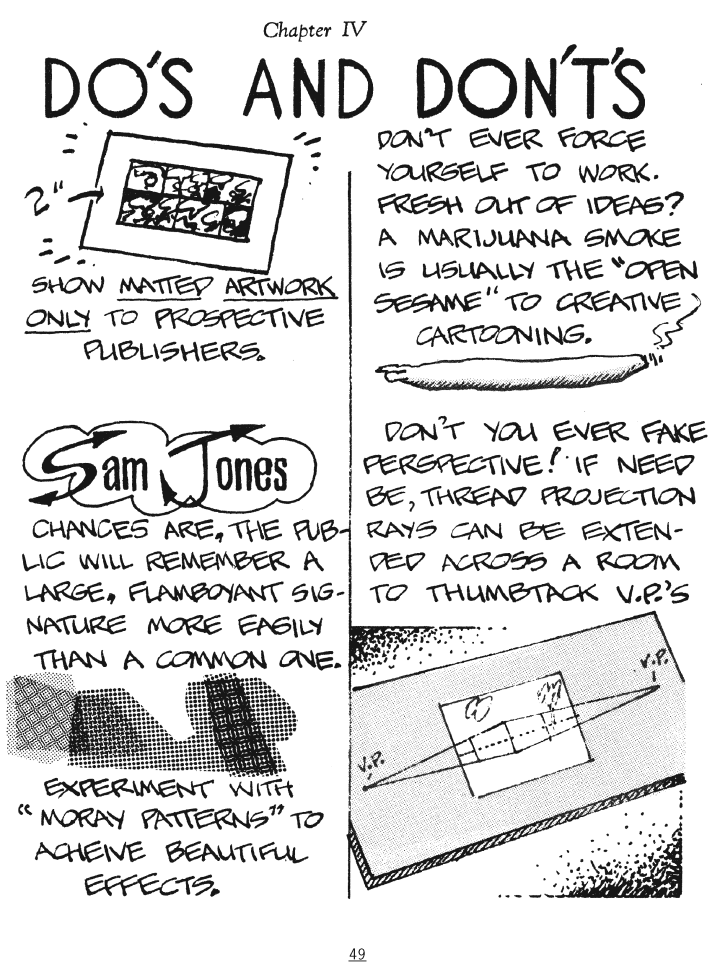

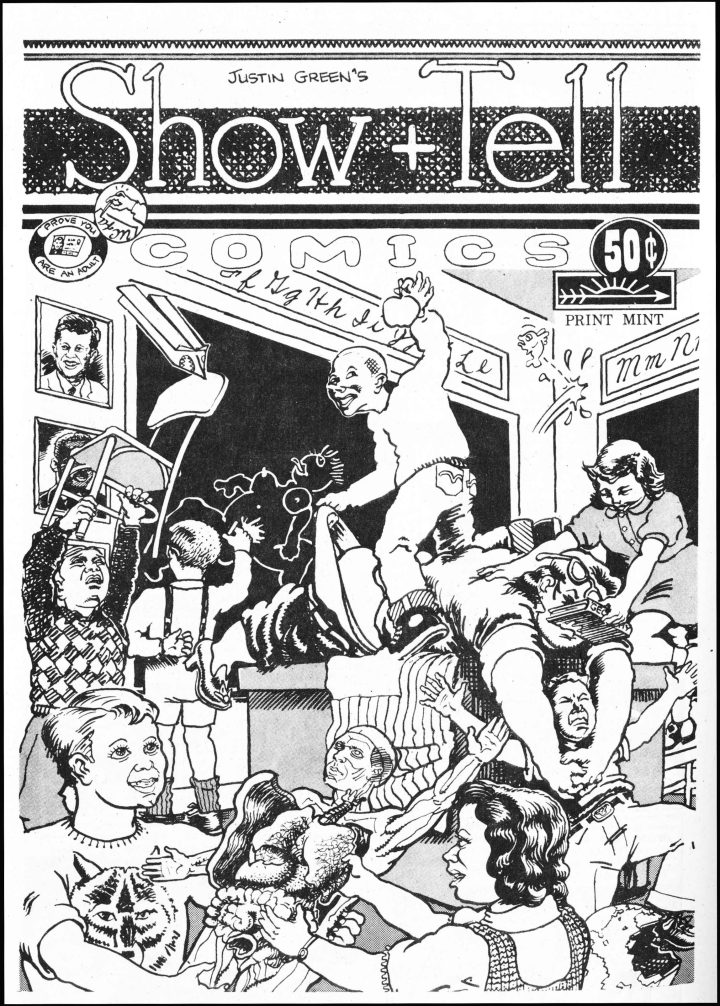

What seems to remain of undergrounds survives in so-called Newave comix, mostly in the form of self-published minicomix. This is a healthy outlet for beginning cartoonists and artists, but the format remains commercially unfeasible. From certain statements made in The Comics Buyers Guide, nothing makes fans like Don and Maggie Thompson happier than declaring the death of undergrounds, but their viewpoint seems a biased one. I would be the first to admit that at least half of the undergrounds published (an admittedly non-scientific estimate) were crude, raunchy, and pornographic; but that the other half consisted of fine work by artists like Corben, Crumb, Metzger; Jaxon, Shelton, Griffith, Irons, Colwell, Spain, Kinney, Deitch, Lynch, Holmes, Spiegelman, and many others whose names don’t jump immediately to mind. Another name that does jump to mind is Justin Green. Green was there from almost the beginning, and is, in the words of Gary Arlington, “One of the biggies.”

Like George Metzger [interviewed in Journal #87], Justin Green is one of my personal underground favorites. His comics didn't stay buried in my collection of undergrounds: I reread them often, and to this day, I find many of his strips endure the test of time.

Justin Green is the genuine article. His comics were like no others, and they left a lasting impression.

I first contacted Green about doing an interview several years ago when Cascade Comix Monthly was still being published and I was still living in Miami. Finally, when I moved to San Francisco in October of 1982, one of the first things I did after getting settled was contact Green about getting together for an interview. We met several times and two taped conversations were the result, the combination of which follows.

Underground comix may well be dead, but the classic work published during the late ’60s and early-to-mid ’70s lives on, just the classic work of EC lives on.

The underground comix phenomenon was a special period in comics history, and its passing should not be an occasion for mourning, but for fond reflection. There is a great deal of work that deserves to be remembered. The work of Justin Green must be included and remembered.

—Mark Burbey, November 1983

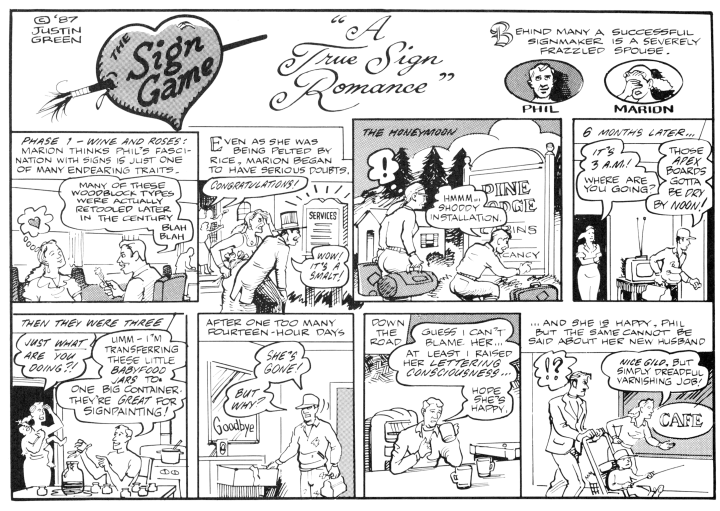

JUSTIN GREEN: $300 worth of signs today, and they have to be done tomorrow and the rest of the week, and so tonight I have to do my patterns.

MARK BURBEY: So, you’re going to work while we talk?

No, I’m not going to work, but I’m always afraid of making engagements because of just this thing. And it makes me appear very flaky, but [this interview] has fallen through so many times that we have to get on with it.

But I have to let you know this was all a very long time ago for me, this underground cartooning, and I still have plans of doing more cartoons, but my early work, to me, is like the trail of a snail. I am the work of art. My work is my shadow. I don’t associate myself with it that much. I still feel empathy with some of the work that I’ve done, but not that proud of it. I’d say I was “on” 10 percent of the time, and a lot of it was just pot-boiling, just to make the rent.

Well, a lot of people don’t seem to agree. They look at it differently. They see it as being some of the better stuff that was done, and that it stands apart from a lot of what was being done in underground comix.

I take that as a compliment. I don’t consider myself to be that thoroughly immersed in the comic tradition. I had a very eclectic kind of orientation.

I learned how to read and write from Fox & Crow Comics when I was four or five years old, and then I went through the standard Scrooge, Donald Duck routine. Then I became kind of fixated on Superboy, as a budding neurotic. Then I totally disavowed comics, oh no, wait a minute, I had a brief fling with St. Rock. It was kind of like the … it gave vent to my repressed macho fantasies, the need to become a man and thinking that I had to prove my manhood at some future time on the battlefield. That there was something to be learned from the camaraderie or men under stress. But mainly I wanted to look like Sgt. Rock, but it slowly dawned on me that I would never have these highly masculine characteristics. [Laughter.]

Was there a gap between when you read Superboy and Sgt. Rock, or was it around the same time, or what?

Yeah, it was, you know, steamy adolescence. But I always liked the way Superboy was drawn in the late ’50s. There was something, the clarity about it, there was something about this world that, to me, expressed objective truth.

I just remembered. one of my great influences was Treasure Chest comics which was a Catholic comic that was distributed free, although the nuns thought it was kind of a questionable venture.

Why?

Because the comic book, the tainted medium, even though it espoused …

It was such a wholesome comic, though.

Yeah, but still, it was slightly risqué to be getting this comic book. Nevertheless, Sister Cora Maria would give us our Treasure Chests, and I would really get off on it. In fact, I prayed that I would someday be a cartoonist. It was a tossup between fireman, priest or cartoonist.

And also, I really liked Heckle & Jeckle as a kid.

The cartoons or the comic book?

The comic book. But mostly it’s Fox & Crow and Superboy. And then I had this totally disavowal of comics all through adolescence.

How did that happen?

I grew out of them. I guess. I started to like Salvador Dalí, Edward Hopper, the socio-realists; I used to go down to the Art Institute of Chicago all the time, the great Impressionists…

What age was this?

From 14, on, all through my teens. The world of art opened up to me, and comics seemed pretty thin fare indeed. It wasn’t until I was in Rome, studying paining, as a senior painter, that I saw Robert Crumb’s work in an underground comics. And it was an electrifying experience I had seen his work in an underground paper in Philadelphia in 1966. In fact, I even met him, unknowingly: I was crashed out on speed on a pile of coats at a party and there was this scrawny guy drawing me, that I found most annoying. And it wasn’t until I met him years later that I realized and he confirmed, “Yes I was in that circle of acid-heads in Philadelphia in 1966.”

The underground paper was an issue of Yarrowstalks, and I submitted a drawing of some asinine thing; two pigs in a police car, and it said “pork” on the side instead of police.

But when I saw “Itzy and Bitzy” in Rome, to me it was like a call to arms to take up the pen again. And Also, being in another culture, I became acutely aware of my own roots. I couldn’t relate to this Renaissance art, this varnish-encrusted, largely Christian or royalty-inspired kind of patronage art. It seemed very distant. So, I started out to think about the things that had formed my own aesthetic, which were, of course, television, movies and comic books. I’d always been kind of ashamed of that and felt that I had to look to other cultures and other eras for inspiration, but something happened when I saw the Crumb piece.

So, you bounced back?

yeah, I bounced back. First discreetly, doing closet cartoons. I continued to do these abstract paintings, but I would sneak these absurd, comic images into them. Like a turtle in a dish or something.

Dalí did things like that. He’d pepper his paintings with exquisitely rendered flies and ants and whatnot.

I kind of grew away from Dalí. I guess a lot of people are inspired by something, and it’s like a bridge the burn behind them. You turn on it. And now I think of Dalí as kind of a grandstanding showman. I like some of the other surrealists a lot more.

Like who?

Like Max Ernst, because his work stays much closer to the raw level of hallucination. He doesn’t gild the lily as Dalí does. He stays close to image-making faculty.

What did you feel Dalí was doing?

Dalí, well, at first I was just amazed by his technical prowess. But then slowly I saw him as just taking piecemeal all these divergent symbols and just polishing them like an old 17th century painter. And to me, that’s stilted. It doesn't have the excitement. It doesn’t convey the acidity of paining. It’s more like a pastiche of looking back at something that has happened and just taking a photo graph of it. And now the market is flooded with all these lithographs that he’s doing.

So, anyway, I saw the Crumb piece in Rome, I came back, my conscientious objector appeal was voted down, and I was in constant turmoil, and it looked like I was going to be drafted all the time. It seemed like comix were a very vital medium in the late ’60s around the time of Yellow Dog and Gothic Blimp Works. It seemed they were a real forum for this alternate culture. There was a great belief that this alternate culture was undermining the repressive powers that were causing all this suffering, which, of course, didn’t turn out to be all that it was cracked up to be.

What was the first actual comic you appeared in?

A friend of mine, the Mad Peck, he was really a seminal influence. He encouraged me in my drawing, and he was a very knowledgeable music critic. He did all kinds of little cartoons with the help of assistants, and he published the Providence Extra. John Peck was his real name, but his stage name was The Mad Peck, and he’s really well-known on the East Coast. I wonder what he’s doing today. I haven’t spoken to him for at least five years. He’s probably in radio. He’s real knowledgeable about ’50s rhythm and blues type music. And he put together all these taped cassettes. He also co-authored, along with Les Daniels, one of the first coffee table books about underground comix. Extremely intelligent guy.

So, what was your first published strip?

It was “When I First Knew There Was Something Fishy About the F.B.I.” It was about a counterfeiter who published these flawless bills, and nobody could spot these 20s. They were just impeccable. But finally, through a series of chemical tests they found out that the ink he used would fade when a certain kind of acid hit it. But to all appearances the ink was the perfect color. So finally, they bust they guy, and in the last five minutes of the show, it shows this guy being hauled away by his commie cohorts and being pulverized, and he’s saying [assuming Russian accent]: “but comrade, those bills was perfect!” [Laughter.] Because the F.B.I. wouldn’t give this guy the satisfaction of telling him that he’d done a good job. They said, “Oh, a common clerk spotted these bills.”

When I was kid I’d seen this TV show and it seemed like dirty pool, so I linked the F.B.I. with this foul play. It was just kind of an anecdotal cartoon, which I seem to find the easiest to script. It’s much harder to do an ongoing slapstick piece than it is to reminisce and select details. Sort of tell a story about the past.

Where did a story like “A Sad Tale’’ [Show & Tell Comics] come from? How did that come into your mind?

Oh, from constant hassling with kittens. Watching this acid-head mooning over a box of deformed kittens …

Deformed kittens?’

Yeah. I was in this household where there was some vagrant who was allowed to stay there. He kept dropping acid and listening to the same Janis Joplin album over and over again, gazing mournfully at this box of kittens that had to be taken to the SPCA but he didn’t have the heart to do it. Who know where that story came from? I don’t know where my material comes from per se. I always find that in the doing of a piece my perceptions change. That, to me, is one of the exciting things. about the medium. You’re not following by rote an initial idea that you’ve set down in words. When you get into the drawing of it, the internal logic of each piece suddenly unfolds. But now I know that the hardest thing is a decent punch line. Splash panels are very cheap, but so few stories resolve themselves … now I think of the comic form as kind of Grimm Brothers tales, that there has to be that moral at the end. It doesn’t have to be so blatant as a lesson to be learned, but there has to be some kind of resounding truth that, is expressed in the end.

What do you mean by a resounding truth?

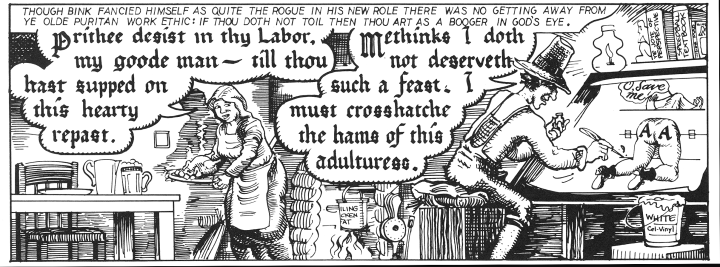

Well, a paradox, ·a twist ending. … I haven’t worked out a formula. I just know that the last panels would be worked out a formula; I just know that the last panels would be worked towards it. And this strip that’s on my board now, “The Man Who Would Be Colonel,” went through drastic alteration until finally it came to this ending. It took me like six months to write it, and it seems very simple, but it, isn’t, because so much was thrown away. It took me 20 or 30 hours to get to that place, which is why I can’t do comics now. Financially it’s unthinkable. I just have too many responsibilities.

This is the one you’re doing for Esquire?

No, I’m going to do it for Weirdo.

Have you done anything else for Weirdo?

No. Crumb had wanted to reprint an earlier piece, but I told him I was ashamed of it.

Which one was that?

I don’t think it’s ever been printed: It’s just some science fiction piece.

How many pages is it?:

Just one, but I can’t even look at my early stuff. It just seems so stilted …

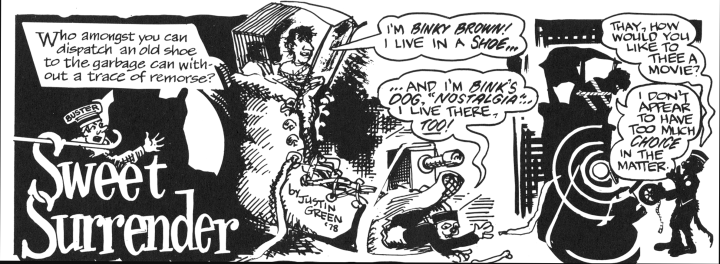

Binky Brown, can you look at that?

Oh, Binky Brown holds together; but still, it’s kind of shocking for me to look at. I’m not especially proud that I put so much of my internal life on the line. At the time it. was right. The publisher wants to reprint it now but I don’t know if I want it to be publicized again. I want to move on. I have other things to say, and I think autobiography is fine at a certain stage in your development, but then you have to grapple with other dynamics of storytelling.

Well, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is a pretty standard underground classic.

I wonder how standard a classic it is, because this stuff is really ephemeral, you know? How much of it is retained in memory by anyone? It’s meant to be entertainment.

It seems like people who were really into undergrounds and who have them all, those people tend to have a few favorites, and Binky, I think, happens to be one of them.

Well, that’s good to hear. But I think a lot of people felt that undergrounds were just too raunchy.

A lot of them were.

In fact, I wish I could, somehow, undo some of the work I’ve done. It was just done in this spirit of constant productivity. Very little of it was worked over, consciously, to the point where it was given enough time to develop as a story. More often than not, I was meeting a deadline on the last day possible, the last hour possible. Once I went to the printer with Spain [Rodriguez] at 7 o’clock in the morning.

Were there actually deadlines for these comix?

Oh yeah, absolutely. In fact, there had to be, because there was a discount for three or four books printed at once, so you’d really gum up the works if you delayed your piece. It was really like having the fire on to do that. Looking back at my work, a lot of it was sensationalistic, adolescent, perverse …

Many artists feel less than satisfied when looking back over past work. It’s just that you’ve grown beyond what you did before. You might, in ten years, look back at what you do now and feel the same way.

I don’t think I’ll have this disparity that I have now. I feel like my consciousness is beginning to settle. I’d like to think I’ll be doing comics, but financially I’m just in such a bind right now.

Do you see anywhere in this country where you could find a market for your work?

I’d like to publish a book without a spine. That’s my goal. I’d like to illustrate some of my writing. I’ve been writing a lot about my sign painting, the characters I’ve met along the way, incidents I’ve been involved in, revelations that I’ve had. I’d like to really wire the whole thing up with a bunch of drawings. I saw a piece by Kim Deitch that really excited me, about him and his brother Simon reminiscing over their East Village days. It was a crazy story about how they had to cop some speed for Simon, and the Pope was in town and he saw Simon and waved at him, and then Simon wound up in jail, but he left the speed in a phone booth or something, and it was like a ratio of one drawing per paragraph. To me it was really an eye-opener of a new form.

Where did you see this?

I don’t know. I saw a Xerox, and right before Kim left town, he told me that there had been Victorian literature like that, with a heavy ratio of drawings to words, but I’ve never seen anything like it. But that, to me, is an exciting possibility because, comics, pure comics form, is so time-consuming, the logistics of getting the balloons right with the right action and so forth …

Edward Gorey does something similar; he does these macabre little storybooks, with drawings and accompanying captions …

I would work in a much more linearly …

His style is to have one caption, one picture per page.

Yeah, but the sheer tone of his work, the man-hours involved in churning out textures like that are phenomenal.

All the little-cross-hatching …

Yeah. I like to work in a much more contour line, a much more fluid line. It’s funny, a lot of people think of me as loose, but I think I’m really much too tight. I really aspire to have a fluid line. I’m real excited by this pen that I lost the last time you were here, that I found, a Pelican drawing pen that uses India ink. It really just freed me from constant dipping

Like a fountain pen, basically.

With a flexible quill, which I like, and no more dipping. So, I can focus on the drawing a lot more, and it has changed my style.

This page you’ve got on your board now, “The Man Who Would be Colonel,” I see that you’ve done all the lettering first, in ink, and you’ve only just started to lightly sketch in the actual artwork.

I usually work in a series of roughs, and then when the story congeals, I have action reduced to a number of panels. Then within each panel, I tighten up on the dialogue, and I know that the dialogue usually occurs towards the top, so I can place my balloons down before actually drawing the balloon. That gives me more control over the placement of figures.

Is it easier to work with the page cut in half the way it is?

I always cut my pages in half because I like to be right on top of it when I draw, and if I have to lean over to get to the top, it’s a strain on my neck. I don’t value the originals that much. My originals always come in collaged and pasted up with lots of re-touch white on them, because I work for reproduction. I think that the aesthetic of doing real nice originals is much more of a print-making tradition, although Crumb’s originals are just fantastic. They’re so clean. He uses an X-Acto to dig up the lines that have gone awry. Although in his old age he’s turning to Liquid Paper, despite the toluene fumes.

I decided on Weirdo (for the piece) because Crumb has been asking me for a long time to do something. The time has come. The last issue (#6) was really chaotic to me. I appreciate his publishing this young talent, but they really have turned their backs on some of the laws of the medium.

Have you mentioned this to Crumb?

No, I haven’t. So, this is consciously a clearance of the story, in a traditional mode, because I think that this kind of piece has not been represented enough in Weirdo.

In The Comics Journal #78, there was a review of the Kim Deitch Eating Raoul comic, and the last line was, “With Kim Deitch back, can Justin Green be far behind?”

In what context do you think that was meant?

Oh, it was in a complimentary, hopeful context, from the standpoint of some of the old underground folks doing some new material.

I’m tired of leading a nomadic life.

How long have you been a nomad?

[Laughter.] Well, officially since about 1979. But before then, before the marriage, I had always moved moved moved, constantly, and now, I can’t do it anymore. I’ll be 38 this year, and so when I finally do get settled in, and I can finally look at this crap and boil it down to like 10 cubic feet, I’ll have just what’s essential to me·. It’ll be a time of great streamlining and clarity. I feel it’s also a race with the social climate, which really disturbs me. To me, it’s almost humorous that we’re talking about this one period in history that occurred, especially about something so specific as my artwork when, in fact, the world is on fire.

Yes, well, that is true.

We all deal with it in different ways.

I tend to deal with it in, just that, I don’t feel like there’s a damn we can do about it. I think it’s all in the hands of the governments. They all have their fingers on all the different little buttons.

Well, there is [something you can do about it], You can bring light to the people around you.

Right, well, you can always try. But then there’s television to contend with.

Television is really disorienting to me.

I hate it. I gave my set away when I moved out here.

Who knows, there could be, over the next few years, a revolution in the video medium. There’ll be all kinds of small, freelance productions that will be disseminated just like videocassettes. In fact, I have one right here. I did this with some of the Duck’s Breath people in the summer of 1980, and it’s a parody of the Charles Atlas commercial. I scripted it out and I drew little diagrams and I acted in it. I had sand kicked in my face, I lost my girl … I like it a lot. It was originally 14 minutes, and then it was boiled down to about three minutes by the Video West people; they’re a local production company and they’re really professionals, and they didn’t like it. ‘When it was being shown, there’d be like a little blip on the film, like a little blemish, and they’d go, “Awww.” It would occur during a great line of dialogue, and I’d say, “What’s wrong, what’s wrong?,” and they’d say, “We can’t use that film. When it’s going on the air it has to be smooth.” So, the thing, as it stands now, is really …

This is only copy you have?

Yeah, but I’m going to give it to one of the actors soon. It was an experiment, and I thought for a while that I would get into video, but I was so disturbed by the technical process of editing, which is more than 50 percent of the work. It’s very mechanical. There are all these machines, and every second is clocked, and then there’s all this button-pressing, and at that point I kind of lost control of it. The constant hassle of getting people together to shoot, it seemed like a monumental pain in the ass. I’m much more of a loner, I guess, so then I returned to cartoons, because you have total control over the medium. You do it at your own leisurely pace. No one’s to blame but yourself for technical shortcomings.

It was an attempt for me to take my cartooning in a new direction. I did sketches of all the main scenes, all the camera angles, but it just demanded too much energy. It was a good experience to write and act in this dramatic form, but I had no idea of the technical demands of editing.

PART TWO: October 26, 1983

At one point in our last conversation, you were saying that with the world in such a state of turmoil, it seemed rather trivial to be sitting here talking about comics. And in light of what has happened this week, what with over 200 Marines being killed in Beirut, and the invasion of Grenada, perhaps the discussion of comics seems to be more trivial.

I think underground comix, came out of a very volatile period in American history. It was a time of heavy polarization of ideas between generations, and we had youth on our side, with this tremendous righteousness and optimism. Things that had absolutely no artistic merit, had more of a political thrust. As the years go by, it’s more difficult to rely solely on sloganeering and heavy-handed symbolism to make an artistic project valid. Very little, oh, I can’t say that — I won’t say very little — but as the years pass, you look over the body of your own work or the work of your peers, not everything is gold. Everyone’s career was uneven.

That was all during a time when the hippie movement was very big and it was lots easier to live on nothing.

That’s right. The sheer economics of producing comix was such that you could live on $300 to $400 a month. You could get by on that amount of money, whereas today that’s entirely impossible. So there just isn’t the available space to create work that there once was.

I don’t assume that the artists thought so much about it as a “career,” or as furthering their career, as they did about the work on the drawing board at that moment. I don’t know if they really thought of it as, ‘‘Well, I’m an underground cartoonist and this is my career.”

Well, there was a bit of ego involved, in the sense that there was a tremendous hope that one’s vision would be appreciated and realized by thousands of readers, as we were speaking to a mass audience. I, myself, at the time, had letters that I more or less solicited from famous people who I sent my work to and returned letters of praise. As the years go by I see that those letters had their value. They made me, in my mother’s eyes, a legitimate artist, not a pervert. They made Binky Brown ’71 somehow a bona fide work of art, instead of this tormented, perverted expose of my own worst fears. And also, I used one of the letters to get laid. I showed this woman that I cared nothing for fame, and I ripped up this letter from Fellini. I was laid 20 minutes later.

Was it worth it?

Yeah!

Who were some of the other letters from?

Well, let me explain: the letters were somewhat ambivalent in their praise. Kurt Vonnegut wrote this really, uh, this postcard that had a strange gratitude. ‘‘Thank you for doing this. Now I understand what it’s like to have a Catholic boyhood. You are a beautiful revolutionary.” Stuff like that. I called him up. I got his number because we had the same dealer on the East Coast.

The same dealer?

He was into weed for a while. And I said, ‘‘Hello, this is Justin Green.” ‘‘Who?’’ ‘‘You remember, I sent you my comic.” ‘‘Oh, yeah, yeah , yeah.’’ ‘‘Gee, did you really remember? Did you really, all those things you said, did you really mean that?’’ And he said, ‘‘Well, yes, uh, I was mildly amused, but I could see that the whole production came from a permanently damaged brain.” [Laughter.]

You get your fingers bruised a little if you go searching for a star. But that postcard helped me with my mother.

Did you show your parents Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary?

Well, my father passed away in 1970, and I bet that I never could have done Binky Brown if he were alive. In fact, while I was working on Binky, I had dreams about my father, in the form of a dangling telephone. I was going down this long spiral staircase and there was like a dangling phone. He was always on the phone, he was an industrial realtor, and his voice on the phone said, ‘‘Such things have never been discussed in public.’’ It was an indictment.

But you did the book anyway.

Yeah.

What did your mother think of it?

Well, she said she laughed and cried, but now I learned later she had terrible health problems at the time. So, who knows what she felt? In the end, you can only do the work out of internal necessity. Anyone else’s acceptance or rejection or praise is immaterial. The work has to stand up on its own merit.

In my own mind, it was much more difficult to do The Sacred & the Profane, to do We Fellow Travellers. That was a true artistic challenge. It’s easy to get an autobiographical mode and play around with your past and lie a little bit and use real and fictional material. But to create symbolic characters and put them into a slapstick story is really heavily demanding.

With We Fellow Travellers originally appearing in Marvel’s Comix Book magazine, wasn’t there also a deadline pressure?

That’s right. That’s another thing. You had to have these revelations on schedule, which was to me such a terrible pressure. I’d rather do any arduous form of sign painting. I’d rather get up on a 40-foot ladder to re-paint a neon sign on Mission Street any day than to have a profound religious insight by next November 15th, you know, and have it down in cartoon form, and also have it function as a slapstick joke. And for $100 per page, which is nothing.

What was it like working for Comix Book for Marvel?

I thought of it as working for Denis [Kitchen]. He was kind of like the go-between. He was very accepting and supportive, and not too much pressure, except when he felt pressure, I guess, from the editors. The deadlines were absolutely hard and firm, but many times I was able to milk a couple of extra days if I promised on my Catholic word of honor that it would be in the mail. And that way I wouldn’t have to have a grammar check or whatever the hell it was.

But it was brutal. All those years, you know, just a slave.

A slave to the pen?

Yeah, and also, you know, I was a marijuana addict.

An addict?

Yeah, I smoked all day, not constantly, but every day I would smoke marijuana. That had a lot to do with my perceptual aptitudes. It made me very introspective.

BURBEY: But when I hear the word addict … a heroin addict is a true physical addict. I don’t think with pot …

The demand is not so strong, but there is a subtle laziness.

There’s a psychological habit you can get into, that’s true.

It kind of warps your will.

If you have it in the house, though, you’re bound to smoke it.

That’s right. That’s my problem. There’s always an excuse to smoke. But also, my wife was pregnant at the time [of We Fellow Travellers], and she was really distraught about the wages I was making. She was thinking, “What kind of future is there with this guy who draws these cartoons?”

Was that one of the reasons the marriage ended?

Well, I tried to be a sign painter exclusively, but I always kind of backslid into cartooning in our early days. But yeah, there was a terrible economic bind, and the fact that I still had artistic pretensions really grated on her, because she was in this grueling survival mode, which is what motherhood is. It’s the most intense, demanding occupation there can be. So, all of a sudden my artistic dilemma was not all that important to her, although she was a really avid supporter before she got pregnant. And I understand it. My notions about what an artist is have really expanded since I stopped cartooning.

How so?

Because I’ve been in the real world for seven or eight years now. Every day I deal with people of every nationality, every economic strata. I give them what they want, letter-wise, graphics-wise, and I’ve gathered a lot of material, in note form. But I look back at my old work, my prolific days of constant deadlines and meeting production schedules, and the work has this ivory tower vibe to it, like it’s all hallucination from a safe, uninvolved vantage point. Because all I was doing was just drawing by myself and then sending the work off to some magazines.

Wasn’t most of your work done for underground publishers here in the Bay Area?

Oh, towards the end it was more like, uh, stuff in New York: Apple Pie and Comix Book. Yeah, there was always local stuff.

In The Best of Bijou, it said that Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary sold around 40,000 copies.

Well, I think now it’s up to 50,000 because it’s sold out. The publisher wants to reprint it, but I don’t want to reprint it until I write another story that kind of brings Binky up to date. And so, there’s a continuity between the early Yellow Dog Binky (“Binky Brown Makes Up His Own Puberty Rites”) and then, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, and then “Sweet Void of Youth” which is Binky Brown as an artist in the real world, in The Sacred and the Profane. And finally, “The Resurrection of Binky ‘Brown,” and that’s what I’m threatening to do if I get solvent.

Ron Turner [Last Gasp] wants to do it?

Yes, but I don’t want to just reprint Binky Brown because it’s really time-warped.

Would he reprint all three stories plus a new one?

Yeah, it would all be one edition.

How long would the new story be?

I don’t know anything about it. I mean, I just know that I want to, uh …

Do you know what it would be about?

Well, it would deal with neurosis, religious crisis, sexuality.

Would he be in his lace 30s by this point?

[Laughter.] I’m afraid so.

There was some connection between Uncle Sol and Binky that we were talking about last time, that we didn’t get on tape. What was that?

It was a mentor relationship. It was actually like, uh, Virgil was the guide of Dante through the Purgatory. Virgil was a Roman poet, and he was the guide and senior of Dante, who’s constantly elucidating for Dante what they’re both perceiving. And Sol is like a middle-aged Jewish man, which is a very comfortable persona to have around me, coming from a semi-Jewish background, because they have a very humorous and confident cocksure orientation to the world. They’re not troubled with the baroque guilt that Catholics have managed to back themselves into. And also, they’re at ease with themselves. I had at one time entertained notions of revamping Purgatory using Binky Brown and Sol. That’s another long-term project, but I don’t know how many ideas you can cherish without actually coughing them up. Ideas are cheap. Anybody can have a great idea. But let’s see what gets inked, let’s see what finally makes it to the press. It’s a whole other story. I don’t even like to talk about ideas before they’re formed, because they lose some of their energy. But let me just put it in a nutshell and say I hope I can find the time in my life to realize some of these ideas I have in note form.

And you want to do Dante’s Inferno as comics?

More the Purgatory, yeah.

Would you work straight from the text?

Oh yeah, I would do my homework, absolutely.

I mean, would it be altered in some way?

Oh sure, it would be in a present context, but I would use the same idea. For example, where Dante might encounter a musician who was popular in the 13th century who was a personal friend of his, I might encounter a musician who died who’s a personal friend of mine. Or maybe I could meet Gene Vincent.

I was talking with Gary Arlington recently, and he told me about how when you were doing Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, he stopped by the house one day and you had all the pages up on wires with clothespins. And when he came in you started taking all the pages down, like you didn’t want anyone to see them. Do you recall that incident?

No, but I like to look at everything while in progress. I began work right in the middle. It wasn’t a sequential kind of thing.

You didn’t start with page one?

No, so I had to have an overview.

But why did you take the pages down when Gary Arlington came in?

I don’t remember. It’s funny that he would remember that because I remember that [S. Clay] Wilson and Spain came over once and I let them see it. Who knows? Maybe it was my 49th acid trip or something. [Laughter.]

Are you at all aware of mainstream comics?

No, and I was kind of contemptuous of revering any polished Marvel or DC artist, although I’m sure there’s a lot of bona fide talent in that area. My interest in it is much more off-the-wall and homemade. It’s just that I learned how to read from Fox & Crow comics, and I had a perverse fascination for Superboy, but it has to be Superboy from a certain era. It has to be like this bland, uh …

It can’t be a Superboy story that’s done now, but in that early style?

No, there were these three guys. One was, I think his name was Wayne Boring, and there were two other guys. I never really researched it. I just knew something about the style that was to me like objective reality, and Superboy’s perceptions of the world always created this living hell for him, where he had to be super-aware of his responsibility in a larger context. No matter what little dialogue was going on with Lana Lang, you know, he still had to be aware of this horrible magnet that Lex Luthor had that could totally change the face of the earth. Yet it was still drawn in such a nice little, h.o. gauge, kind of folksy objectivity with that nice contour line, like Will Elder had.

Really clean cut.

Of Davis and Wood and Elder, I always preferred Elder.

Because he was neater?

Yeah, he just had this sculptural line. I think Davis and Wood were more like true pen & ink artists. They had this kind of energy, this kinetic energy about their line, but Elder was much … I think he used a brush …

Really? A brush?

I think … I’m not sure.

Elder’s comics were always drawn with such control and neatness.

Yeah, they’re real clear, and there’s something about comics, because of the reduction of the scale, where it demands a clarity.

Another subject we’d discussed that never got on tape, was the subject of cruelty in your work. The element of cruelty that exists in life. A piece that pops to mind was, I think, a back cover for Yellow Dog, showing this dog eating kittens out of a cardboard box, with. a girl scout crying, “Why doesn’t God stop him?”

I never forgot that piece, it made such an impression. It was somehow fascinating.

These various pieces that you mention to me, I’m grateful that you would recall them, but to me they’re so long ago, it’s like remembering a Halloween party in the third grade where somebody was bobbing for apples. You know what I mean? It’s like these really far-gone memories. Having a child is really mind-expanding, and I often wondered what it would be like if I’d had a child as a younger man, and then I became a cartoonist, if it were at all financially possible. I think my work would have a much different bent.

Maybe you’d be Bil Keane [Family Circus].

Hey, he’s not bad. Many times …

I’m not putting him down. I like him sometimes, but you and he are from two different worlds.

But more and more I want to appeal to all age groups. I definitely think that underground cartooning was a male phenomenon. Women kind of dropped out, with the exception of women who did cartoons for their feminist audience, which is very small. But the main thrust of underground cartooning was this male-oriented world, especially younger males, college age and younger. I know there are exceptions. I’m not trying to be critical. Or am I? I’m just saying, I’d like to appeal to all age groups with my work.

Is it really possible to appeal to all ages?

I guess I can’t answer that one intelligently.

A teenager and a 50-year-old might not respond to the same things.

Not necessarily. Look at Walt Kelly, look at the great cartoonists we’ve had in this century, and they have this universal view.

Walt Kelly’s work was something special and it had a satirical edge to it, but often when you try to appeal to all ages, the edge is gone. The work becomes more rounded …

You have to watch your language, and …

Even the language can be skirted around, but the main thrust of it isn’t always as sharp.

But when you speak of a main thrust, that implied a kind of art that confronts. Do you have to be so volatile in all, your work? Can’t you just try to be funny? I really like Gary Larson, for example.

Oh yeah, The Far Side. I like that a lot.

He’s like 98 percent funny. Now I think he’s a universal artist.

True, I guess there are good ones who can appeal to all ages.

Yeah, so if I can’t do that, I would rather paint signs, than to be like, uh, one of these wiseacres. I mean, it had its place for me in my artistic development, and my development as a human being, and I’m not being critical of my peers who still follow that path. But for me, at this time, it doesn’t have that compulsion, that desire. Whatever it was that made me forsake all practical concerns, to just cast my fate to the wind and trust that if I followed what was most important to me that all my financial needs would be taken care of, is gone.

But you have to do that project, whatever it may be, if you want to go on to the next step and keep cartooning.

That’s right, especially when you consider a daily strip, where you’ve got to come up with six weeks of finished work, in other words, 30 daily strips. Forget about even marketing the thing until you have 30 ready-to-print strips, and that’s a tremendous expenditure of energy. It’s a six-month project.

Assuming you had the time, would you want to pursue a daily strip concept?

Sure. Absolutely.

Would you rather do a one-panel thing, or a strip, or what?

I don’t know. I have lots of little experimental strips, many directions. There are too many dilettantes. I don’t want to be just another dilettante. If I’m not going to do it right, I’d just as soon be a sign painter. I don’t want to dabble in the arts.

Getting back for a moment to the subject of cruelty in your work, do you think there might be less of that in your work today? Did that come out of something that might not be a part of you today?

Well, it’s a part of the human condition.

Cruelty always seemed to be a lurking aspect of your work. It would always pop up someplace. Rowdy Noody would often by pulling some cruel prank on an innocent little boy, a dog would be eating a girl scout’s kittens, etc.

You mean sadism?

Not so much sadism, but things that seemed unfair and would perhaps make you feel like crying.

The doctrine of reincarnation is really assuring to a lot of people. A lot of people say, “I don’t believe in God anymore,” they reject the Christian cosmology and then they turn to these Eastern ideas like reincarnation, because it’s gratifying to think that there is karma, that there’s a fate you endure in this life and then it’ll be rectified later on, depending on your performance in this one. So that there is some overall justice why you were born, whether you are lowly born or nobly born, as they said in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. But it just so happens that there’s a lot of random violence out there. What wisdom or knowledge can be gained from enduring it?

I know I had a lot of frustration in my life, as a younger man; maybe I needed to express that in cruelty on the printed page. But now I don’t really feel that need to revel in the gorier aspects of living and dying. I’m really repulsed by looking at a lot of my early work. I can’t stand to look at it. I don’t even own it. Whenever I’m moving I always stumble across three or four comix or drawings that come flying out of a sheath of papers, and I am astounded that I actually had drawn this at one time.

Just last night, I was watching an excellent public television documentary about Vietnam, and there were my contemporaries (I’m 38), breathing their last, taking their last swig from a canteen, some stray bullet, wrong turn, and they’re dead. Why them? Wasn’t Vietnam strange that it touched so many lives and yet there was a great detachment from among those who didn’t go?

Those who didn’t go really didn’t know what it was like, and they probably didn’t want to think about it more than they had to. It was just one more problem. That’s the way most people deal with things that are out of sight, out of mind. But the people who it did touch haven’t forgotten it, and they never will forget it.

I don’t think any of us will forget Vietnam. How do we justify that some people would buy these ideals that would permit their selflessness, sacrifice, and other people would feel not called upon or even contemptuous?

People have differing views. Today, Reagan has his supporters and his dissidents. Some approve of what he did in Grenada recently, ochers strongly disapprove. It was the same with Vietnam.

The Vietnam war really figures into the whole birth of underground comix.

Why then wasn’t that more visible in the actual work? Why did so much of the work seem to be about dope and sex? There wasn’t much direct political comment overall. Basically, it was just dope and sex comix.

The whole idea that an alternative culture could function, if there was this name “alternative culture,” as if there were this secret pocket of existence inside of the beast that thrived on the brotherhood, the underground brotherhood of shared beliefs and ideals, that it was just taken for granted that you’d be against the war.

Was it felt to be enough of a statement simply to tum your backs on the bourgeois society and ideals that give birth to the Vietnam era, rather than directly attacking the political establishment? Is that what you’re saying?

Yeah, I guess so. I guess I would buy that. Although, there were artists who confronted the Vietnam war: Greg Irons, Tom Veitch, Spain.

Did any of them go over there?

I don’t think there was any underground cartoonists who had military experience, except maybe Ted Richards. I might be wrong.

Anyway, this question of cruelty in my work, there’s still a fascination I have with the somewhat arbitrary nature of misfortune and death, that some people endure, and the luxury, and pleasure and difference that others have access to. It’s really a mystery to me.

I was talking to my girlfriend about fate. Her father, she’s German, and he was in WWII, and he was left-handed and this guy he was with was right-handed. In the course of something they were doing, their elbows kept bumping each other, so her father suggested they trade places, which they did, and the next moment, he nudged his buddy and there was a bullet hole in his head. He was dead. Otherwise, it would have been the other way around …

Otherwise, she wouldn’t be your main squeeze. She’d never be born.

Exactly. Fate works in a thousand different ways. Wasn’t your brother, Keith, involved in underground comix at one point?

Yeah, he was into distributing and selling, and he concocted all these deals that were based on, uh, package deals; buying a certain amount of comix and getting a certain discount for your larger volume of sales, and there were some disgruntled artists. I never really did get to the bottom of all this, but I sincerely believe that he had the artists’ best interests at heart. He’s selling fine art now. He’s really making a fine living in New York. In fact, he sold a Gauguin to President Marcos for $1,000,000. [Laughter.]

Something tells me we’re in the wrong line of work.

Another topic we got into last time that never made it on tape was religion. Religion has played a very big role in much of your work, not too unlike the films of Luis Bunuel. You went to Catholic school for only three years, right? But it left a real dent in your psyche, nonetheless?

Afraid so.

That you still can’t shake?

No, I can’t. I think that the Christian cosmology touches on a very fundamental orientation to life that people from all cultures have, and that you can be an absolute monarchist and a Christian, you can be a Marxist and a Christian, you can still find solace in this person who supposedly lived 2,000 years ago and who died on the cross for our sins.

But do you believe in God and the whole thing?

Do you mean am I a practicing Christian?

No, do you personally believe in God?

This is on tape? [Laughter]

Would you go so far as to say you’re an agnostic, or do you believe there is a God of some sort?

Well, today I was driving along and you know how it is when you are in a two-lane situation, and there’s some obstacle in the traffic in front of you? In the first lane, there are people the people behind the guy who get trapped there and try to get out, and then the people in the fast lane are able to just drive by. The other people are kind of screwed, they can’t get out, they have to wait. So, I slowed down and I honked my through horn so that one of these trapped individuals could get into the fast lane. First he signs, thanked me, and I didn’t acknowledge his thanks; it was all right. So, he was driving ahead of me, waving his hand out the window. Like there was this current of energy we built, from my act to him and from his acknowledgment of my … [Laughter]. I know that sounds trivial. I’m just trying to explain, you asked me if I believed in God. There’s definitely a current of benevolence we generate toward each other as human beings. Maybe because of the horrific responsibilities of vengeance and cruelty that we are capable of giving vent to, we have to codify our aspirations for good in symbolic figures like Christ and his sacrifice. It’s a myth, and yet orthodox Christians claim it’s more than a myth, that it’s an actuality, an historical fact. I guess I can’t buy that, yet I can subscribe to the myth. The message therein is that we have to die to this world, to go that beyond it. And yet, to me, it’s so complicated with sexual repression that the message of organized religion is all but meaningless.

I believe in Man. I think we’re still capable of extricating from this cliffhanger of nuclear holocaust that we’ve somehow backed into. I think that the whole global situation now is an external manifestation of the psyche of man that is polarized into opposites of good and evil. The whole human consciousness has evolved to the point where we have this very strong fear and very concrete sensibility of ourselves, that we are good and bad. We’ve done it on a global scale now. The Russians feel the same about us as we do about them, that we’re good and they’re evil. It’s possible that we can take that leap now, that we can go beyond that, that we can seek a higher ground, somehow this arsenal that can kill every one of us, and incidentally all hamsters, 340 times over, you know, there’s enough for death to the 30th power for all of us, every living being on Earth, that somehow human consciousness can make that leap that we can somehow squelch this. You have to believe that.

I believe that logic will prevail somewhere along the line before the proverbial button is pressed.

What about terrorists? What about religious fundamentalists? What about extremists?

Well, I don’t think we can relate to those fanatical mentalities.

And yet that might well be a greater threat than the so-called collision of the super powers, like fringe elements who have access to nuclear powers that can leave a nuclear weapon in a van in a major city.

So, some of us believe in-God by getting on our knees, which I did as recently as two years ago, the morning after I drank a quart of tequila, and others are able to express God through humor.

And that’s how you do it — through humor?

No, I express God by painting signs.

In your work, one might assume you’re trying to purge yourself of whatever religious doctrine might still be with you. Would that be true?

Yeah, I felt a lot of anger from my repressions I’ve gotten as direct result from of ingesting orthodox Catholicism. But I’m beyond that now: into seeing it as a much greater phenomenon. I still can’t separate.

I haven’t done my homework is what I’m saying. I’ve tried to many times. It goes back to my chaotic living situation.

Would you really call yourself a loner?

Yeah, I guess so.

Do you like being a loner?

It has its drawbacks. I guess I’m just starting to seek people out. For years I just felt like a victim of my economic-situation. I was just too tired to get out. I worked myself into unconsciousness. I’ve got a little extra time, there are certain people I seek out who give me a lift.

You got some tape left? I’d like to play you my latest tune. I just happen to have 12-string here …