Mort Walker, whose tour of duty on Beetle Bailey was the longest run of any cartoonist in the history of the comics pages, died Jan. 27 of pneumonia at the age of 94. Though once banned from the pages of Stars and Stripes, Walker, a World War II veteran, was awarded the Decoration for Distinguished Civilian Service in 2000 and will be eligible for a military funeral. The strip, which Walker launched in 1950, settled into a depiction of the downtime of U.S. Army enlisted men as broad comedy — a lighter, postwar, stateside version of Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe cartoons. Walker also co-created Hi and Lois with Dik Browne, and the two cartoonists and their sons went on to found a comic-strip dynasty that at one point generated six simultaneous daily strips and occupied a large portion of the funny pages. Walker was president of the National Cartoonists Society from 1959 to 1960. His Wilton, Ct., home and studio were in convenient proximity to New York publishers, and a large community of cartoonists slowly gathered, drawing, socializing, drinking, and playing golf together. Walker launched the Connecticut Cartoonists Invitational Tournament and continued to run it for more than fifty years. In 1974, he founded the nation’s first comic-art museum, which after several relocations, resides at Ohio State University and boasts the largest existing collection of comic art.

At the time of his death, Walker had been cartooning professionally for an astounding 80 years, having sold his first cartoon (to Child Life) at age 11. By the age of 13, he had sold roughly 300 cartoons, and was drawing a weekly newspaper strip called The Limejuicers for The Kansas City Star. Walker achieved these feats while attending middle school and migrating between dust-bowl, oil-boom towns in Kansas, Texas, Ohio and Missouri during the Depression.

He was born Addison Mortimer Walker in 1923 in El Dorado, Kan. His father, Robin, was an architect and painter and his mother, Carolyn, was an illustrator for The Kansas City Star and Kansas City Journal. His father contributed hundreds of illustrated poems to the Star, which ran them on the front page of every holiday edition of the paper, often with drawings by Mrs. Walker. With the father frequently unemployed during the Depression years, the family went without heat, plumbing, or electricity and collected dandelion leaves to boil for dinner. The Walkers raised four children, two daughters and two sons, but Addison, in particular, seemed to inherit the artist’s yearning to communicate with a broader public. Interviewed by Shel Dorf in the Nov. 30 1979 issue of The Buyer’s Guide, he remembered his father, despite all the hardships, laughing at Chaplin films and comic strips: “And he would laugh so hard he would fall on the floor. … I wanted to be in the laughter business.” The young Walker knew everybody in high school and became the president of every club and editor of every publication, including the YMCA, the Art Club, the Debaters’ Society, the school paper, and the yearbook, in addition to forming a Cartoon Club, managing a biweekly dance, participating in an acting group and the cheerleading squad, and getting elected vice president of his class — all while pursuing a brisk career selling cartoons to national publications and working as staff cartoonist on a dairy company publication. The only area he didn’t excel in was being a student.

Impatient with the part of schooling that involved sitting in classrooms, Walker only reluctantly enrolled in Kansas City Junior College. He worked nights in the shipping department at Hallmark and responded to an artist-wanted ad, which turned out to be a position upstairs from where he was already working. Walker was hired and immediately began introducing the heretofore uniformly sentimental Hallmark greeting cards to the gag cartoon. Barely out of high school, he started a trend that transformed the greeting-card industry.

Both his greeting-card career and his matriculation were nipped in the bud when he was drafted into the military at the end of his first semester at the University of Missouri in January 1943. Like Beetle, Walker spent much of his time in the military being prepared for various combat roles that never materialized — including time in the Air Force Signal Corps, the Army Specialized Training Program, and an assignment as an infantry scout, during which he practiced invading islands off the coast of San Diego. His military education included Officer Candidate School in Fort Benning, Ga., and an associate degree in engineering from Washington University in St. Louis. (While stationed at a barracks dormitory adjacent to the university, he recalled, he regularly snuck out at night, fashioning an outline of his body under his blankets and crawling through furnace ducts.)

Unlike Beetle, Walker eventually got a taste of the WWII European theater. Shipped to Italy in 1945, he was put in charge of a POW camp housing ten thousand German prisoners. He found he was sympathetic toward the prisoners, who often escaped overnight and returned the next morning. “It came to me somewhere along the way that I didn’t really care if the POWs did escape,” he wrote in Backstage at the Strips. “They never did anyway. Most of them were just poor suckers like I was, waiting to go home and trying to make the best of it until they got there.” As an intelligence officer, he investigated a murder, robberies, rapes and other crimes in Italy.

Honorably discharged with the rank of first lieutenant in 1946, Walker returned to the University of Missouri in Kansas City, where he bypassed journalism school prerequisites and took over editorship of the college magazine, ShowMe. It was popular with students and made the national news when the university censored a sex-themed issue featuring a student survey, but it did not endear him to university administration. When it was discovered that Walker hadn’t taken the required courses, he was kicked out of the university’s School of Journalism, but he managed to take the magazine with him by turning it into an off-campus publication. Despite such clashes, Walker accumulated enough credits to graduate in 1948, and, today, the university has a life-size Beetle Bailey statue on campus.

Moving to New York, Walker was hired at Dell to edit several magazines, including Western Stars, Film Fun, and Hollywood’s Family Album. During his editorship of Dell’s 1000 Jokes magazine, he shifted the emphasis from verbal jokes to cartoons.

In 1949, Jean Sufill, ShowMe’s ad manager and a fellow cartoonist, became his first wife. He took his drawing gear on their honeymoon and the following week sold four honeymoon-themed gag cartoons. His work on ShowMe had been noticed by Saturday Evening Post editor John Bailey, who welcomed Walker into that magazine's prestigious showcase for cartoons. A 1950 survey found Walker to be the bestselling gag cartoonist in the country, but even so, he judged the market to be insufficient to meet the financial needs of his growing family. What he needed, he decided, was a newspaper strip.

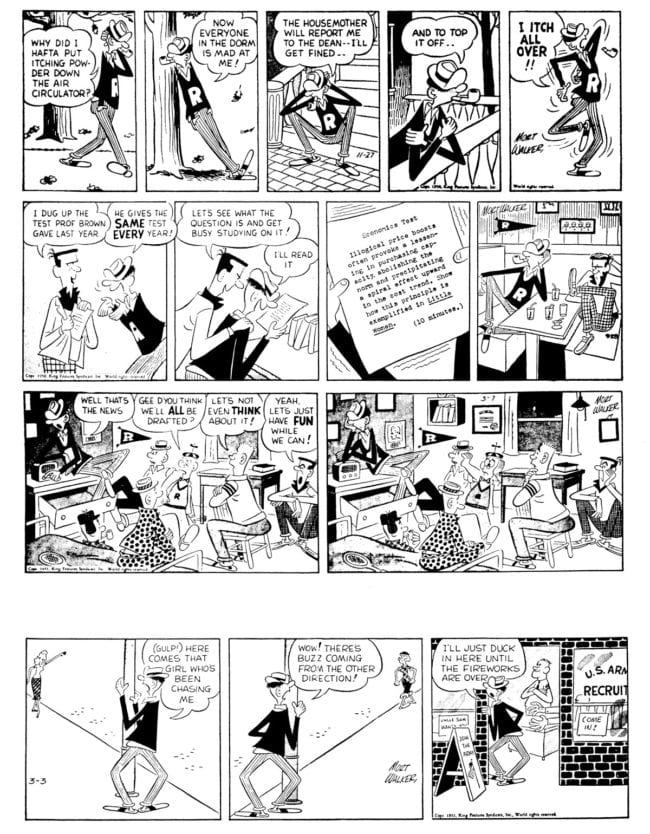

As his strip protagonist, he chose a lanky, work-avoiding college student with no visible eyes, who had been appearing in Walker’s Saturday Evening Post cartoons under the name of Spider. For the strip, the character’s name changed to Beetle, his surname a nod to editor John Bailey. The strip focused on the character’s struggles in the bowels of an educational institution, but it was not popular and was picked up by only a handful of papers. Readership took a large leap forward, however, after Walker shifted Beetle’s environment to the only other institution Walker knew well: the armed services.

Walker feared the country was turning away from the Army and wartime concerns, which would lead to diminishing attention being paid to an Army strip, but it soon became clear that Beetle Bailey was not just an Army strip. The public’s post-WWII preoccupation with the American military may have drawn an initial audience to the strip, but what ultimately sustained Beetle was something more universal. As evidenced by Beetle’s effortless conceptual transition from college (students, teachers, dean) to Army camp (soldiers, officers, general), the details of the environment were not as important as the cast of characters and their relationship to the institution that had arbitrarily thrown them all together. The eternal implication of an impending war that never materialized gave the strip an abstract Waiting for Godot quality that was appropriate to the new Cold War atmosphere the nation was getting used to. The Beetle character, born at the bottom of the totem pole, had been dropped into a bureaucratic limbo and the public identified with his passive resistance. Camp Swampy could just as easily have been an office building (workers, middle management, bosses). “I’ve always thought that I would like it to be a representative of somebody who’s caught in the system that they have to resist in order to exist,” Walker told R.C. Harvey in a 2009 interview in TCJ #297.

Not that Walker had Samuel Beckett or even a critique of military bureaucracy in mind when he conceived Beetle Bailey. Its minimalist abstraction stemmed from Walker’s perception of the ideal strip as an uncluttered space in which gags could be executed with the clarity and inevitability of the simplest slapstick routine. His long single-panel apprenticeship had taught him to think in terms of visual ideas that the reader could grasp in a glance. He avoided complexity and anything that hinted at political commentary. “Being controversial has never appealed to me,” he wrote in Backstage. “While Beetle is a satire on military disorder, it’s a gentle satire.”

Nevertheless, it was controversy that cemented the success of the strip. Accustomed to wartime heroes on the funny pages, like the Air Force’s Steve Canyon and the Navy’s Buz Sawyer, the Army was not happy to be represented by a shiftless enlisted man giving his superiors the finger. The Pacific edition of the military newspaper Stars and Stripes dropped the strip in 1954, sparking media coverage and an outcry from readers. By the time, the paper gave in and reinstated Beetle, more than a hundred other papers had added the strip.

For the most part, Camp Swampy is a timeless place. Drones and Southeast Asian or Middle Eastern tours of duty have no place in the strip. But by 1970, it had become clear that Beetle’s world was not only timeless but colorless, representing the Army as all-white. Walker himself had to admit that this was fundamentally dishonest, since black soldiers are in fact a major presence in the military. Responding to complaints from black readers, Walker introduced Lt. Flap, a black character who managed to be funny without being the butt of the joke or stumbling into racially sensitive landmines. Assertive and hip, he disrupted the white complacency of Camp Swampy, but ended up attracting more readers than he alienated. Among the alienated was the controversy-fearing Stars and Stripes, which again temporarily dropped the strip.

There’s no arguing with success, however, and, like the University of Missouri, the Army ultimately came to embrace Walker and his creation. “They realized that the strip is popular with the GIs and people who had relatives and friends in the Army,” he told Harvey. “They began giving me big citations and medals, you know, for outstanding service to my country. [Laughter.] I got racks of stuff over there, in my office, over in the garage where I file them, stuff they have awarded me. One time, they had a whole parade for me in the South Lawn behind the White House.”

Despite his aversion to political commentary, Walker managed to slip in the occasional anti-war sentiment, but he was for a long time tone-deaf to the sexist, nudge-nudge-wink-wink burlesque routines played out between the leering Gen. Halftrack and his bosomy secretary, Miss Buxley. TV host Phil Donahue arranged an ambush in which Walker was confronted by a feminist guest in front of an audience. Taken aback by the angry response of women readers, Walker began cleaning up his act in the 1980s by dropping the creepier running gags, making Miss Buxley less of a sex object, and ultimately, sending Gen. Halftrack to sensitivity training. “Every now and then when I do a strip,” he told Harvey, “I do an idea sketch and [Walker’s sons and collaborators] Greg and Brian say, ‘You can’t use that one!’ I still have it in the back of my head that it’s OK to tease a woman when you say hello or to whistle at her.”

Sexual mores were also the theme of one of one Walker’s favorite stories: his War of the Belly Buttons with King Features. Walker noticed that the syndicate was cutting out the belly buttons he had drawn on the characters whenever they were shirtless or in swimming suits and responded by drawing two belly buttons on each character — all of which King Features dutifully removed before publication. Interviewed by Cullen Murphy for the July 1984 issue of Atlantic, Walker said, “I began putting so many of them in, in the margins and everywhere, that they had a little box down there called Beetle Bailey's Belly-Button Box. The editors finally gave up after I did one strip showing a delivery of navel oranges.”

Beetle is even more popular in Scandinavian countries than it is domestically. They have no problem with the sight of belly buttons, and gags deemed too lewd for U.S. readers are saved for publication in Norway and Sweden. The strip has had no trouble translating beyond the U.S. and has been exported to more than fifty countries.

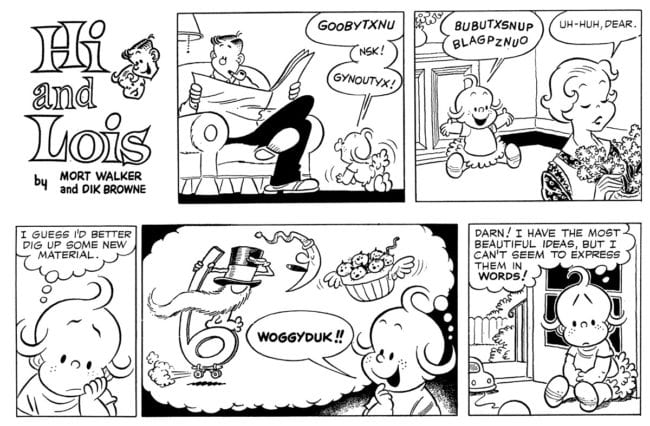

Appearing in approximately 1,800 newspapers worldwide, with an estimated 200 million daily readers, not to mention an animated 1960s TV series, Beetle is Walker’s biggest success, but in 1954, he launched a spin-off strip that came a close second: Hi and Lois. With a truce signed between North and South Korea, Walker believed it was time for Beetle to return to civilian life and interact with a new cast of characters that included his sister, Lois, and his brother-in-law, Hiram. Readers insisted that Beetle return to Camp Swampy, but Walker, surrounded by a new and growing family himself, developed a separate Hi and Lois strip as an outlet for family-based gags. Dik Browne, who had been working in advertising, was hired to draw the strip. A device in which the infant Trixie began to make observations via thought balloon was popular with readers, and the strip’s circulation grew to more than 1,100 papers. Hi and Lois has continued for more than sixty years, passing in the 1980s into the hands of Walker’s and Browne’s sons, Brian and Greg Walker (writers) and Robert “Chance” Browne (artist). (Dik Browne, who died in 1989, was also known for creating, writing and drawing Hagar the Horrible, a strip that is continued today by Browne’s son Chris.)

Mrs. Fritz’s Flats, a Mort Walker creation about the residents of a boarding house, ran from 1957 to 1972, but never carried his signature. Walker came up with the strip based on characters conceived by gag writer Herb Green, intending to give the idea to Green. Walker and Green, however, had a falling out and Walker assistant Frank Robergé seized the opportunity and the strip. Walker wrote the initial gags, but soon turned the writing and art over to Robergé. The strip ended when Robergé suffered a fatal heart attack.

In 1968, Walker launched Boner’s Ark, a strip that took place entirely at sea, with a cast consisting of Captain Boner and an assortment of talking animals. It was another success, both domestically and abroad, and lasted more than thirty years. He signed the strip with his birth name, Addison, but eventually turned the art chores over to Frank Johnson, an assistant who worked uncredited on a number of Walker’s strips. Johnson, began signing Boner’s Ark in 1982, and when he retired in 2000, the strip was ended, with the ark at last reaching land.

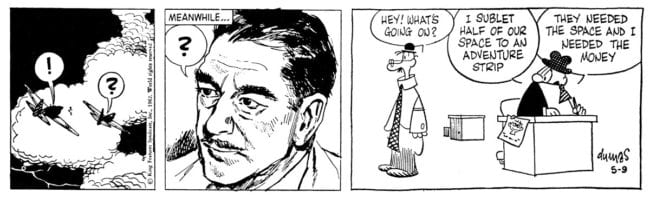

Walker never stopped coming up with ideas for strips, far more than he could write and draw himself. Not all of them were hits with the public, but they employed enough collaborators and assistants that his Connecticut studio came to be known as King Features North. One strip was both successful and unsuccessful: Sam’s Strip, written by Walker and drawn by Jerry Dumas, ran for only twenty months between 1961 and 1963, inspiring amused admiration from cartoonists, but confusing the average reader. The postmodern concept depicted comic-strip proprietor Sam and his cartoonist assistant interacting with various characters from neighboring strips on the page, as well as iconic figures from past strips. The strip was almost always self-referential, its gags centering on formal comic-strip devices and conventions. Dumas carefully imitated the varied art styles of the visiting characters. Cartoonists loved it, but readers wrote puzzled complaints to the syndicate wondering what Blondie, for example, was doing outside the borders of her own panels. When the New York Journal American, the venue where most cartoonists saw it, folded in 1963, the strip was canceled. Fourteen years later, however, the characters were revived as small-town cops in a more conventional strip called Sam and Silo. Sam and Silo has continued to run for more than forty years. Walker withdrew as writer in 1995, and Dumas wrote and drew it until his death in 2016.

Another Walker concept that left many readers scratching their heads was The Evermores, which was drawn by Johnny Sajem and ran from 1983 to 1986. Its protagonists were a single family depicted in different eras throughout history, implying that domestic conflicts were eternal. Readers, however, never warmed up to the strip’s constantly shifting setting.

During the run of The Evermores, Walker divorced his first wife and in 1985 married Catherine Carty, who brought her three daughters Whitney, Cathy, and Priscilla into the family.

One of Walker’s more surreal strip ideas was to combine Felix the Cat and Betty Boop, comic-strip and animation characters dating back to as early as 1919. That was the year of the first Felix silent animation; the first Betty Boop (patterned after singer Helen Kane) cartoon appeared in 1930, capitalizing on the shift to talkies. Both were adapted into comic strips, Felix first appearing in newspapers in 1932 and continuing until 1967, Betty’s strip career running only from 1934 to 1937. Unlike the original cartoon Felix, the comic-strip Felix was able to speak, but when Walker revived him in 1984 in Betty Boop and Felix, he was again speechless. Furthermore, he was reduced to replacing the original BB strip’s Pudgy as Betty’s pet. Felix frequently got the punch lines, however, commenting sarcastically via thought balloon on Betty’s naïveté. Under the signature of The Walker Brothers, Neal Walker did most of the art, Greg Walker did the inking and lettering, and Brian and Morgan Walker came up with the gags. Mort oversaw the whole production line and edited the final results. The strip was popular on the West Coast, but never caught on elsewhere, and the characters took their final bow in 1988.

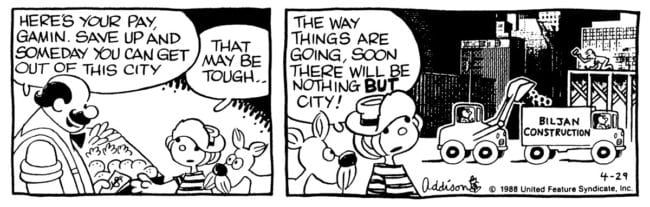

In 1987, under his Addison signature, Walker wrote and drew Gamin & Patches, about the humorous experiences of a homeless child with actual photos of cities providing the backgrounds. A comedy about homelessness, however, proved to be a tough sell, and the strip folded the following year.

As indicated by Walker concepts such as Sam’s Strip and Betty Boop and Felix, and even a retro premise like Gamin’s street-urchin adventures, Walker had a strong appreciation of classic cartoons and strips. He was the instigator and driving force behind the Museum of Cartoon Art, the first institution devoted to the collection, preservation and exhibition of cartoon and comics art. The museum opened in Greenwich, N.Y., in 1973, thanks to Walker’s financial support, energy, and determination, as well as a large donation from the Hearst Foundation. It went through various relocations over the next several decades, including a castle in Rye Brook, N.Y., and a specially built structure in Boca Raton, Fla. Its collection encompassed more than 200,000 pieces of art, representing newspaper strips, animation, comic books, editorial cartoons, gag cartoons, caricatures, and book and magazine illustrations. Its on-site research materials in Boca Raton included ten thousand books and one thousand hours of film and video. The museum was continually beset by debts and survived largely through Walker’s refusal to give up on it. In 2008, its collection merged with the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University.

That stubborn streak was also on display when Walker challenged IRS policies regarding the valuation of original comic art. Taking the position that comic strips are ephemeral and of little value, the government disallowed the amount that Walker had deducted from his taxes for charitable donations of his original art. Walker sued the government in 1970, bringing in expert appraisers to testify as to the high market value of his original art among collectors. He won the case after a week-long trial, setting an important precedent for cartoonists.

Walker knew the value of his work and had enough confidence in his talent and popularity that he stood up to King Features, demanding ownership of his strip. When Beetle Bailey began, the syndicate owned the strip even though Walker had created it, and decisions about marketing and licensing were all made by King Features. When the rights came up for renewal in the 1980s, however, Walker refused to sign them over. The cartoonist claimed ownership of his strips, and King Features ended up paying him $1 million for merchandising rights. Under the new deal, Walker had final approval of all licensed ancillary merchandise.

Throughout his long life, Walker was dedicated to cartooning, never far from the next gag. He received virtually every award and honor the comics field had to give, including the Reuben Award, the Elzie Segar Award, the National Cartoonists Society’s Best Humor Strip of 1966 and 1969, the San Diego Con’s Inkpot Award, the Golden T-Square Award, and the Swedish Adamson Award Platinum. With both parents writing and drawing as he was growing up, he said in Mort Walker’s Private Scrapbook, “I was a teenager before I realized some people weren’t cartoonists.” That tradition has continued, with Walker’s sons highly involved to some degree in the family business, whether working on strips, assisting with the museum or, like Neal, managing the Mort Walker website. Not surprisingly, Walker saw comics as a kind of family. “As society becomes more spread out, family members find themselves living farther apart from each other,” he told Harvey, “and with life becoming more impersonal, comic strips help fill the void in people’s lives by creating the illusion of friends and shared experiences.”

And just as nothing good can come of bringing up politics at a family gathering, Walker declined to venture into the deep waters frequented by cartoonists like Garry Trudeau and Jules Feiffer. “I go along with Leo Rosten,” he wrote in Backstage, “who feels that ‘humor is an affectionate insight into the affairs of man.’ Affectionate is the word that won me. I like people. I like their absurdities, their aberrations, their pretentions.”

Walker did not push the boundaries of the comic strip. But he did as much as anyone to define and sustain the classic gag strip, the kind of Sunday morning comfort food that amused and consoled generations of families in the U.S. and around the world. Dialogue and character traits were important to his strips, but he had no use for what he called “talking-head strips,” and his figures were never allowed to remain static. His humor had a headlong momentum that never failed to deliver the expected surprise conjured from an infinite number of variations on a firmly finite set of timelessly familiar situations.

The “laughter business,” as he called it, became second nature to him, and if the newspaper comic strip ever becomes extinct it won’t be because Mort Walker and his family of cartoonists gave up on it.

Walker is survived by his wife Cathy, his sons Greg, Brian, Morgan, Neal, and Roger, his daughters Polly and Marjorie, and his stepdaughters Whitney and Priscilla.