*This is the second of a two-part essay surveying manga and manga-adjacent media dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, from manga- and anime-based memes and single-page comics-format parodies, to cartoon diaries, graphic medicine, political cartoons, and revivals of older pandemic-themed comics. This part and its prequel, "Corona Cartoons, Japan," focus on work produced or publicized during the first four months of the outbreak in Japan, from February to the end of the emergency order in late May, though spilling over into June. As this essay is a work in progress, written on the fly as time allowed and information came in, any corrections of fact, disputes of interpretation, or leads on other examples would be most appreciated. Please share them in the comments section below.

4. Pandemic Prophecies

Masked faces, anti-contamination wear, invisible microscopic dangers, self-protective quarantine, empty public spaces, and a lack of governmental preparedness and accountability... For many Japanese, the current situation inevitably recalls 2011 and the uncertainty and anxiety that followed the meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power facility, the ninth anniversary of which passed on March 11, just as COVID-19 was achieving critical mass.

In the immediate wake of that as-yet-ongoing disaster, dozens of manga about nuclear power plant scandals and atomic apocalypse were dug out of obscurity and newly celebrated as prophetic. What followed the coronavirus outbreak has been trivial in comparison, perhaps simply because there are not as many manga featuring pandemics. After all, while Hiroshima and Nagasaki are domestic toponyms in Japan, and Chernobyl impacted Japanese life enough to inspire protests in the streets against local power utilities, Japan has not weathered a serious, widespread contagion since tuberculosis in the ‘50s. Even Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys, despite the hemorrhagic virus at the center of its drama, has only been tentatively reappraised in light of the current situation, as noted previously in the section on Abenomask memes. Granted, neither the virus nor its spread is really elaborated upon in any scientific detail in the manga. It is manufactured in a laboratory, sprayed from a giant robot, and later planted by gas-masked men carrying suitcases, causing people to spew blood and die on the spot. I don’t recall any scenes in which one person infects another. Perhaps this is merely a discrepancy in the scanlation I had access to, but the “virus” is oftentimes referred to as “bacteria.” The narrative framework of bioterrorism and cult millenarianism suggest that Urasawa’s main inspiration was the 1995 Aum sarin attacks, with Ebola-like death introduced to dramatize the violence. The underlying structure of Urasawa’s pathogen seems more “germ warfare” than “pandemic” to me.

I could be wrong about this, but there does not seem to be any real discourse in Japan for framing the current pandemic as a conspiracy, unlike there is, say, in the QAnon-infected United States. There is, as a result, limited cognitive grounds to read the pandemic as a variant of biological warfare. Some Japanese bash China for being authoritarian and careless in their response to the virus, but the idea that a weapons experiment went awry in Wuhan has little traction, from what I can tell. Many Japanese were, however, anxious about what Prime Minister Abe might do under a state of emergency with regards to constitutional revision, police laws, and day-to-day social controls. Urasawa’s presentation of virological/bacteriological outbreak as cover for political ends—as the means by which a state of emergency is created in order to take political control, smear and eliminate opponents, and create popular support through fear—are readymade to be read allegorically through such concerns, but I have seen scant evidence that they were. It perhaps speaks to a lack of political sensitivity (or paranoia) among manga watchers that masks and pathogens, rather than conspiracy, are what have been spotlighted in Urasawa’s magnum opus since the outbreak. The Friend-Abenomask memes (discussed last time) are the only gestures I have seen in this latter direction, though I suspect other examples could be found if one dug further. The muted tones and conservative interpretive leaps are, at any rate, in stark contrast to the Japanese tendency to read all atomic motifs and nuclear technologies in relationship to mushroom clouds. Even the scientist who fabricates the virus in 20th Century Boys describes her sin in post-atomic terms: “I am Godzilla, I have trampled over 150,000 people.”

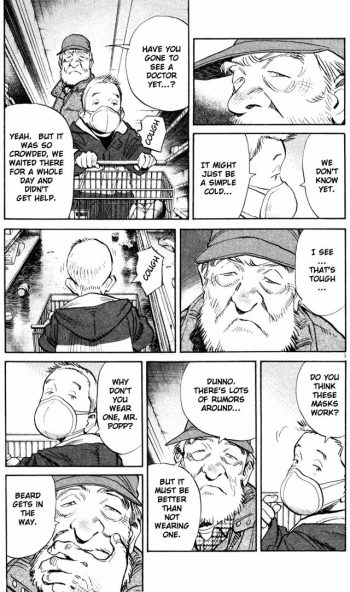

Meanwhile, a significant buzz collected around Hokazono Masaya’s Emerging (2004), about a novel Ebola-like virus that leaves a trail of grossly hemorrhaging bodies across Tokyo while an underequipped and crisis-denying Japanese medical establishment fumbles the initial response. A three-volume thriller originally serialized in the popular weekly comics magazine Morning, Emerging suddenly gained an exponentially wider readership after the digital version was made available for free in March. Alas, it appears that some people mistook the manga’s images of citizens lined up outside drug stores with “we are sold out of masks” signs on the door, doctors in full-body protective gear caring for patients on ventilators in overrun hospitals, and the powers-that-be dithering over the economic costs of pandemic panic as recently drawn, leading to accusations of fūhyō higai (“rumor damage”) against Hokazono. This term has a specific resonance: it was frequently and aggressively marshaled after the 2011 nuclear meltdowns as a means to repress debate over the extent and damage of the radiological fallout from Fukushima Daiichi. Obviously, the criticism is misplaced, as Emerging was created sixteen years ago. As with Urasawa’s Abenomask cartoon, the news media is as guilty as anyone here, creating “fake news” by cherrypicking Twitter threads for trivial signs of conflict and blowing them out of proportion.

Saitō Takao, hoary bannerman of orthodox masculinist gekiga, has issued a number of notable items in response to the pandemic. I have not yet read the collection of Golgo 13 stories related to viral and bacteriological outbreaks, titled Pandemic in English (Kansen in Japanese, literally Infection), that was published in a cheap and ubiquitous convenience store format by Saitō’s own Leed Comics on May 1. Leed published a similar collection related to nuclear meltdowns and scandals after the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in 2011. As Golgo 13 has covered all variety of terrorist threat and political conspiracy since its debut in Shogakukan’s Big Comic in 1968, Leed is well situated to exploit a wide range of disasters in the years to come. Since April, Duke Togo (a.k.a. Golgo 13) has also featured on Saitō Pro’s (Saitō’s studio) Twitter account @saitoproduction in simple, brightly colored memes juxtaposing the squared jaw assassin and such sayings as “Fear alone keeps us away from danger” and “Don’t stand behind me,” the latter long used by Saitō to boast of his own pioneering greatness but now directed at shelter-in-place and social distancing recommendations. The studio has more recently used characters from other Saitō manga in similar COVID-19 PSA.

Most momentous was the announcement on May 8 that Golgo 13, which has appeared in every issue of Big Comic for the past 51-plus years, would be suspended, hanging at episode number 599. So momentous, in fact, that the decision was covered by major national newspapers like Asahi Shinbun and the public broadcasting network NHK. The reason provided in a statement signed by the editorial board of Big Comic and published in the magazine’s May 25 issue (published on May 8) is interesting from a comics history perspective, as it attributes the suspension to the untenability of studio production under conditions of social distancing. “Since the declaration of a state of emergency on April 7, the novel coronavirus continues to spread. As Saitō Pro employs more than ten people on a principle of divided labor, we have decided that it is too difficult to continue the production of gekiga as usual.” The statement goes on to say that “everything was done to try to ensure that readers would continue to have new episodes to read.” However, “the increased risk of infection due to daily commuting to the studio, confinement in close quarters for an extended period of time, and the necessity of drawing directly on assigned sheets of paper mean that our production process violates all three of the three Cs.”

I visited Saitō Pro in 2011 in order to interview Saitō. If the place looks and operates now like it did then – crowded, airless, and hyper analog – and it appears it does, disbanding the studio was indeed a wise choice. Of course, though an economic division of labor has been central to the mythos of Saitō Pro since the ‘60s, studio production methods for making manga have never been specific to “gekiga.” It is the rare manga artist today that doesn’t use some kind of studio method. “The physical presence of the staff is indispensable” to the creation of serialized manga, assert Saitō Pro and Big Comic. But ever since the advent of quality drawing and graphics programs, that is obviously not true. My friend Torikai Akane, a rising women’s manga star, reports that she and her assistants having been using Dropbox and video chats with few problems. On the publishing side, another colleague, Yoshida Rō, head of the women’s manga publishing house Shu Cream, said to me in June that his staff largely works from home now, with the company buying computers and tablets for those who need them, and select employees going to the office on alternating days, with very few problems. Printers, however, according to one of his editors, are operating exactly as they were before: all hands on deck and around the clock. After all, as of May, total book sales were up by ten percent in Japan versus the previous year, and manga sales by a full fifty.

It would seem, therefore, that Saitō’s brand of gekiga has fallen, not to the pandemic per se, but to a stubborn commitment to a dated national work culture of interminable hours in highly structured physical offices and the corollary opposition of “teleworking” from home. COVID-19 won’t be the end of studio practices in manga – that would essentially mean the end of the industry as we know it – but it may accelerate the marginalization of paper-based cartooning and the macho group work ethic that manga has historically shared with other Japanese industries. Golgo 13 was recommenced in July, though I am not sure under what kind of work conditions.

5. Corona Musings and Graphic Medicine

Let’s turn now to new multi-panel comics. Not single-sheet parodies like the items described last time, but strips and multi-page comics. Most common have been the short, one to three page works in the diaristic and “manga reportage” (comics journalism lite) genres popular in newspapers, online magazines, and social media.

In early February, before COVID-19 had become a life-changing issue in Japan, Cameroon-born, Japan-raised cartoonist and radio personality Hoshino Rune began touching on the virus in his monthly, two-page series Double African Boy News, a collaboration with half-Japanese, half-Cameroonian comedian Takeuchi Kirara (a.k.a. Black Samurai) for the web magazine FINDERS. In the first such episode (February 12), the impact on Japan is still largely at a remove, with Japanese tourist sites suffering from the near evaporation of Chinese guests and the turning back of Chinese cruise ships from Japanese ports. The second page is given over to premonitions of the coming regime of social distancing in the form of fans at Disneyland and Johnnys music events not being able to physically interact with their idols and vice versa. Things get marginally more serious in the second installment (March 17), as Abe issues grave warning and public events are cancelled, but then turn trivial again with advice to shy boys who won’t be able to finally confess their love to their sweethearts at their middle school graduation ceremonies (the Japanese school year ends in March) to not fret too much since they will have plenty of time to do so once the virus passes. April’s episode reports on the global spread of the virus and the things people around the world are doing to stay sane under home quarantine, like New Yorkers applauding healthcare workers every evening and Spanish police dancing and playing music. Hoshino has touched on hygiene measures in some of his other comics, all of which are available on his Twitter account @RENEhosino.

Also early, Gokayajin @gokayajin, who makes diaristic travel comics about his time in developing countries, published one on February 25 about being discriminated against in an undisclosed third world Asian country populated by people of color (presumably India) for being East Asian and thus feared as a carrier of the virus. As the boys and women stare at him suspiciously and whisper “corona, corona” loud enough to be heard, suddenly an ogre of a man brandishing a metal ladle chases after him shouting the same. If the manga shows how the “yellow peril” discourse newly marshalled against China has impacted other people of East Asian descent and nationality, it also shows how easy the stereotypes are to dispel in some places, with the artist and his assailant becoming friends in the last panel.

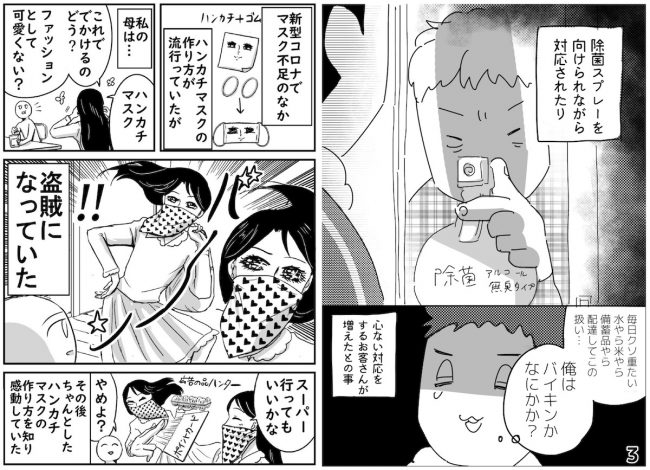

Most COVID-related diary manga have been about domestic matters, and most of those are made by women. Naminiwa Machiko’s Princess Mother (Purinsesu okaasan) series, about a young plucky housewife who dispatches her family of three’s domestic problems with wit and panache, included a chapter about stylish homemade masks (March 21 @manga_m) before that was a fad in Japan. On April 18, as part of her series of simply-drawn comics about childrearing and daily life, Shibuya Saera @voxxx posted four pages about the discrimination her husband faces as a parcel deliverer. “My family aren’t bacteria [sic],” the narrates declares, after an elderly person shoos her husband back from the front door during a delivery and insists on receiving the package with rubber medical gloves. At another house, a person answers the door with a spray bottle of disinfectant aimed at his face. “Please remember that it is because people like my husband continue to work outside that life is able to go on as it does,” the artist pleads at the end.

Short works of graphic medicine (known as “iryō manga,” or “medical manga,” in Japanese) are even more prevalent. From mid March into April, Aburanuma @minddive_9, award-winning author of the two-volume All You Ever Wanted to Know about Pharmacists: A Cartoon Introduction (Manga de wakaru yakuzaishi, 2019-20), created a number of four-page comics tackling facts and rumors pertaining to COVID-19 for the digital version of Asahi Shinbun, one of the country’s major national dailies. Among the topics treated are the low likelihood that infection will lead to pneumonia and the importance of researching legitimate medical advice from places like the WHO before believing in quack remedies like eating garlic. Starring a middle-aged mother and her hysteric elderly mother, Aburanuma’s series is targeted at a senior audience anxious about their higher fatality rates and adult children with baby boomer parents. In a pair of comics on Twitter (March 16 and April 7), Aburanuma details how to protect yourself from “Corona-chan,” the virus as a cute but threatening, chick-like blob with a crown of spikes around its head. In the latter of the two, soap is personified as a beautiful woman and the lipids protecting the virus as an affectionate girl who clings to the soap before being ripped away by a whiplash of water.

Of a more sustained and focused nature are the educational one and two-page comics of a group known as Mizika Shu (meaning, I believe, A Helping Hand), active on the internet and Instagram. Comprised of three women (an art director who specializes in using drawing as a social communication tool, an NGO project manager, and a speech and hearing therapist) who first met through events for children with Down syndrome and their parents, Mizika Shu describes their project as an “inclusive communication support tool” and themselves as a “social unit.” Since mid April, they have been crafting soft, easy-to-understand, three-panels-per-page comics designed to help children with learning and other disabilities and their parents gain a better grasp of the complexities of the pandemic and navigate the disruptions it has caused to their daily lives. Topics include how to protect oneself from the virus, the importance of regularly washing your hands, why social distancing is essential, how to combat the loneliness of not being able to see your friends, relatives, or teachers, how to organize your time while stuck at home, why parents are suddenly working from home, and the meaning of “state of emergency.”

Though Mizika Shu had originally planned to issue these comics for free online through social media outlets at the rate of one or two every week until the emergency declaration was lifted (which happened on May 25), the series continues as of present writing. This series in particular reminds me of the large number of manga created after the Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns in 2011 that addressed the health concerns of expectant mothers and children faced with radionuclides in the air, on the ground, and in the food chain. Like then, there is a decidedly maternal angle to most diaristic and medical manga responding to the current crisis.

6. Via China

Interestingly, some of the earliest coronavirus-related manga circulated in Japan were created by the Chinese Consulate General in Osaka @ChnConsul_Osaka. Reportedly designed for Chinese students stuck in Japan, the series is in Chinese and is titled simply Novel Coronavirus (Xinguan bingdu). The first installment, posted March 10, is a two-page allegory about how to protect oneself from the virus, with a skyscraper standing for the body and a girl in dark clothes and dark skin (colorism?) representing an invading virus. On her headband is a pompom-sized icon of the virus. In a four-page follow-up on March 19, the girl is blasted by spherical drones labeled “lysosomes” (an enzyme membrane that is understood to be a key pathway in the coronavirus’s infiltration of cells, I believe) which frees her from the virus. Subsequent installments, which get increasingly racy – the final, seventh episode was posted on June 23 – talk about how coronavirus RNA replicates inside the body and how healthcare workers combat the virus. My Mandarin is no longer functional. But even if it were, I wonder if I would be able to decipher this fairly technical comic, the viro-allegorical construction of which is manifold more complicated than what you find from Japanese graphic medicine cartoonists, whose work is more about protective practice than, as here, scientific exegesis.

Of greater reach is One World, One Fight! (Shijie jiayou!), a joint Chinese and Singaporean production that garnered press in Japan due to its quick translation into Japanese (among a number of other languages) and promotion by central players in the developing inter-Asian coproduction and licensing of comics. Originally issued online for free in Chinese and English in mid April, One World follows public health and frontline healthcare workers in the virus’s epicenter of Wuhan as they struggle to understand the novel pathogen, raise public awareness, and save lives. A vertical scroll-formatted, color web comic with dramatized expressions à la young men’s action manga, a wide variety of infographics, robotic dialogue, and an absurd amount of redundant captioning – I haven’t seen a comic that visually describes the action it depicts so extensively since American comics of the ‘50s – One World is a slick-looking but artistically stiff product that at least succeeds in communicating what appears to be its primary goals: a better understanding of how the virus impacts the body and a better appreciation of the difficulties faced by healthcare workers. Overall, but especially in the heroic masked faces and the details of donning and doffing personal protective equipment, I sense the influence of Tatsuta Kazuto’s Ichi-F: A Worker's Graphic Memoir of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant (2013-15), though this time the protagonist is a woman, as are many of the supporting characters.

The production background of One World is perhaps more intriguing than the manga itself. It was created by Koowa in China (an editorial group from the popular comics app Kuaikan Manhua) and Gen Z Group in Singapore (“a group of finance professionals that are crazy about manga” and produce “original educational graphic novels” and educational programs, according to the company’s webpage). The comic is a dramatization of clinical guidelines and experiences set out in Handbook of Covid-19 Prevention and Treatment, an open access resource for healthcare workers based on what was learned from the outbreak in China, published in mid March by the Jack Ma Foundation (of Alibaba fortune) and the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. According to Graphicmedicine.org, the project was inspired by the “Global Call to Creatives: An Open Brief from the United Nations” issued in late March, which offered to help artists in efforts to translate “critical public health messages into different languages, different cultures, communities and platforms, reaching everyone, everywhere.”

In Japan, One World is known, I think, mainly through its promotion by Sadojima Yōhei, formerly of Kōdansha, who oversaw such hits as Inoue Takehiko’s Vagabond and Koyama Chūya’s Space Brothers (Uchū kyōdai) as an editor for the magazine Morning. Sadojima is now president of Cork Inc., a self-described “Tokyo-based manga artist management and literary agency” that “co-develops new works with writers and manga artists, and then manages their intellectual properties globally through multiple media,” especially in Japan and Asia. “It is unfortunate that we weren’t able to mobilize a manga project like this first in Japan,” Sadojima reflects in a preface to a chapter of the Japanese edition online, “but at least I can offer an excerpt here in Japanese thanks to our Chinese partners.” Cork has worked with Koowa and Gen Z Group on the Chinese edition of the manga Investor Z (Inbesutaa z), originally a Morning serial, by Mita Norifusa.

However one judges One World as a comic, one should at least recognize the significance of this being potentially the first time non-Japanese parties have taken the lead in producing Japanese language content in response to a crisis. I have a hard time imagining Japanese audiences getting exciting about a comic of this caliber. I especially have a hard time imagining Japanese conservatives – who, as we saw with the backlash against Okamoto Ellie’s cartoon, keep a predatorial eye on cultural output – taking well to content sourced from their much-maligned Communist neighbor. But even if one glosses over its medical advice, One World still reminds us that we are probably not too many years away from Tokyo being challenged as the sole production center of manga in Asia.

7. A Small World

Let me close with two works of a slightly different nature. Though lacking the humor and satirical edge typical of diaristic manga, as seen above, they originate in a common desire to document and communicate personal everyday life. Though non-medical in nature, they share the heartfelt interest in mutual care and the gentle, babyish aesthetics that characterize practically oriented projects like Mizika Shu’s. Moreover, even if their production and form resemble the fan-driven Amabie boom very little, they nonehetless appeal to the same circuits of distanced connectivity and sentiments of hopefulness that the famed yokai mermaid rode across the globe.

Mokumoku Studio is comprised of Yasui Chikara and Kakeda Tomoko, a couple based in Tokyo who specialize in writing and illustrating children’s books. The name Mokumoku comes from the onomatopoeia for rising clouds and flowering vegetation, chosen because of how it expresses endless formal transformation. “Like woodblocks are painted in various colors, like every word means something, each one of us has a story to tell,” they explain in English on their website. “Mokumoku Studio wants to visualize the fragments of emotions and feelings by fusing them as if they were colorful blocks.”

In that spirit, in early April Mokumoku initiated #concoro, short for “as we find ourselves in these corona times . . .” (konna korona na gojisei desuga), a daily series of two-page comics based on stories about how people are coping with the virus in Japan and around the world, posted on their website and social media accounts @mokumoku.studio. Among the subjects are a woman in Japan worrying about her parents in China, a mother in Tokyo wondering what will become of her newborn child, a nanny in Florida appreciating the increased time she has with the children she cares for, a scientist continuing her research privately, a designer in Chicago thinking about his health, and a translator in North Carolina juggling deskwork, childminding, and lack of exercise. Anxiety about the future, loneliness caused by social separation from loved ones, and concern for less fortunate people course through a number of the episodes. Nonetheless, the series tends to emphasize looking on the bright side, hoping for the best, and making the most of the situation by spending more time with your children, discovering new aspects about yourself, and readying oneself emotionally for whatever will come next. Focusing on individuals in what appear to be relatively privileged circumstances, the series is decidedly non-confrontational, which is reinforced by the soft, children’s book-like quality of the drawings. Posted in both Japanese and English, #concoro concluded on May 6, after twenty-six installments.

With a similarly elegiac and innocent look is Seo Natsumi’s Corona Crisis Angel Diary (Coronaka tenshi nikki) series on Instagram @natseo, begun on April 5 and ongoing. Once an aspiring cartoonist, Seo gained fame in the years after 2011 with her solo and collaborative projects about Rikuzentakata, a coastal village in northeast Japan that was not only utterly wiped out by the tsunami, but then erased a second time when the town’s ground level was raised 20-30 feet through massive earthworks. Seo has since explored resonances of memory and loss between man-made and natural disasters, namely the atomic bombings of World War II and the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and meltdowns. Drawn in Sendai, northern Japan’s largest city, where Seo lives, Corona Crisis Angel Diary stars a simply sketched, Christmas ornament-like angel stuck at home, lounging, looking bored, looking at her smartphone, looking at her laptop, looking wistfully out the window, and cuddling her cat, all the while thinking about the virus.

While the artwork is as fey as could be, the writing is surprisingly dark, beginning with melancholic descriptions of the depression of being sequestered at home alone, the fact that people will be losing their jobs and not getting them back, that people you know might be getting sick and you’ll never see them again, and how anger and frustration are natural responses. These might be obvious sentiments, but ones that are under-expressed in Japan’s generally upbeat cultural response to the virus. Later posts tentatively explore the new “un-everyday everyday” (i.e. the “new normal”), the unknown future to come, and having to come to terms with a permanent state of exception – ideas which were also explored extensively in Seo’s work on Rikuzentakata and post-disaster community. “Why an angel?” I asked the artist, knowing that one featured in many of her tsunami-related drawings as well. “In the current situation, everyone is a witness in some way, maybe too much so. I wanted a character that provided a perspective separated from that, an entity that is perpetually praying for us. Given the tension and pace of developments, I also thought it would be too difficult to write on social media as myself.”

Aside from shared aesthetic sensibilities, there is another reason I grouped these two projects together: their openness to feedback. For this essay, I finally opened a Twitter account in order to hunt down examples and retweet/archive them, knowing that Instagram and the internet were not the primary forums where the action was happening. As an unintended result, I also found myself part of the creative process (mainly through Instagram, ironically). On May 7, Seo, who I befriended after writing about her tsunami-related work for Art in America in 2016, wrote the following entry as part of her Corona Crisis Angel Diary: “A friend in the United States forwarded me a link to someone who is making a series of manga based on the lives of people impacted by the coronavirus from around the world. Stay-at-home, social distancing, honoring essential workers, how to enjoy yourself despite being stuck in your room . . . with a common vocabulary flitting across them, people from around the world feel closer and more familiar than usual. Now is the time when we could become friends. I like that idea.” She is referring to Mokumoku’s #concoro project, which I forwarded to her after they did their aforementioned post about a manga translator in North Carolina (April 30) – who is, yes, me. Mokumoku kindly asked me to share my story after I commented on one of their posts. I, in turn, told them about Rescue Party, the excellent series of 9-panel, Instagram-formatted comics “dreaming about a utopian or ideal future post-virus” being hosted by Desert Island Comics in Brooklyn. Mokumoku’s own heartfelt installment was posted on Rescue Party on May 28.

I conclude with these narcissistic anecdotes to draw your attention, not to me, but rather to an important feature of COVID-19-era cartooning: the rapidity, contingency, and spontaneity of the creative feedback loop, made possible by the near-simultaneity of the pandemic around the globe and the fact that social media (and not just the internet) is the dominant platform through which work is being shared. Of course, the similarities of what is happening between Tokyo, Sendai, New York, and my home in Durham, North Carolina, are only class deep. The specific feedback loop highlighted here is thus also an echo chamber, with only those who have the time to make art (or write about art) featuring in art. I hope that more Japanese cartoonists find both the courage to punch upward, like Nitta and Okamoto Ellie did momentarily with their political cartoons about Abe and economic privilege. I also hope they find the social awareness to extend their empathy downward, to people whose pandemic reality is not the stay-at-home quarantine so often featured in the examples above. Nitta’s broadside and Shibuya Saera’s short comic about her parcel deliverer husband are rare exceptions.

To my knowledge, there is nothing in Japan remotely on par with the political cartooning at The Nib, Mona Chalabi’s political infographics, the creative whirlwind of Desert Island’s Rescue Party series, or what young Chinese artists have been producing (covered faithfully on Paradise Systems’s social media accounts). Despite its reputation as one of the global centers of comics, I fear that Japan lacks both the political awareness and the support structures needed for nurturing the kind of satirical cartoons and on-the-run creative reflections that crises like the current one call for.

The wide world of corona manga nonetheless demonstrates the degree to which comics have been accepted in Japan as a social communication tool and a common language for fan-based parody. Given the volume and intensity of art, comics, movies, and other cultural responses to the 2011 tsunami and nuclear meltdowns, it is a little surprising how thin the output has been in response to the virus, which may speak to the relatively non-event nature of the pandemic in Japan, or, rather, how difficult it is to make artwork about an event characterized by a high degree of non-eventful-ness. Japanese artists have a long history of making works about “disasters,” but this is not what the pandemic has been in Japan. But who knows what things will be like in the coming months?

*For more images of the above-discussed works and additional examples, see @mangaberg on Twitter. Thank you to Machimura Haruka, Takamatsu Mari, and Kajiya Kenji for their help in directing me toward examples.