Although the question of who created Archie is clouded by rival claims from Montana and Goldwater, it may be that both contributed to the conception of the character that became the cornerstone of the publishing company. In official histories of Archie Comics, Goldwater is credited with inventing the characters and Montana with visualizing them. Goldwater usually cited his experiences in Hiawatha, Kansas, as the foundation for his vision of teenage life: as reporter for the local paper, he covered the high school athletic contests, which, in Hiawatha, were among the chief entertainments of the citizenry. Montana, on the other hand, points to his high school career at Haverhill, Massachusetts, where he encountered many people who later became characters in Archie. And the Thinker statue outside Archie’s Riverdale High School is a direct borrowing from Haverhill High.

Goldwater says the “catalyst” for Archie was Superman. “Archie was created,” he told Mary Smith, “as the antithesis to Superman—ordinary believable people with a background of humor instead of superheroes with powers beyond that of any normal being. Innumerable sleepless nights, dreaming and writing and rewriting characters that could catch the public’s fancy as Superman had was not just an ‘idea’ but a conscious appraisal of my experiences in the Middle West, California, and elsewhere. I had gone to school with a boy named Archie who was always in trouble with girls, parents, at school, etc.”

This notion seems at pretty severe odds with the usual supposition (mine, and I’m not alone) that Archie was an attempt to cash in on the popularity of such teenage heroes as Andy Hardy, played by Mickey Rooney in 15 films starting in 1937, and Henry Aldrich, the adolescent protagonist of “The Aldrich Family” on radio from 1939 until 1953—suppositions that Goldwater strenuously denied in a letter to the New York Times, August 21, 1988. And his memory may be more accurate than our speculations: MLJ hadn’t had any notable success with the superhero genre, so Goldwater might well have been looking into other more ordinary crannies for inspiration.

To suppose, for the nonce, that in this dispute, as in most such contests, each side has possession of a part of the truth, we can construct a situation that gives both sides credit for some part of the creation. Maybe it went something like this: Montana (according to his daughter quoting her mother) had been sketching ideas for a teenage comic strip for some years before he began freelancing with MLJ Comics in 1941. He presented his idea for a strip about four teenage boys to Goldwater, who was looking for a feature about teenagers (perhaps inspired, as I say, by the popularity of Andy Hardy and Henry Aldrich; perhaps not). Goldwater then suggested that the cast be reduced to two boys, Archie and Jughead (Forsythe P. Jones, who, incidentally, is named Forsythe Van Jones II in the newspaper strip), and, ostensibly drawing upon his own youthful adventures in the West with the opposing sex, he directed Montana to add a romantic interest, who was Betty Cooper. Vic Bloom is credited with writing the first story, perhaps guided somewhat by the Popular Comics character, Wally Williams, who had a sidekick named Jughead. (Ron Goulart told me that Wally Williams was written by a Vic Boni, who, he supposes, could have been Bloom writing under another name.) (Or vice versa.)

Veronica was missing from the initial appearances of the feature, but subsequently, after the first or second story, we may suppose that Goldwater recommended that Archie’s love-life be complicated by a rival to Betty (again, as Goldwater implied, relying upon his memories of his own escapades with blondes and brunettes in tandem). This was Veronica Lodge, a dark-haired vamp in contrast to Betty’s blonde wholesomeness. With the arrival of Veronica in April 1942, the stage was set for what became the feature’s chief plot mechanism—the competition between the two girls for Archie’s favors, a canny reversal of the traditional competition in which two men vie for one woman. (The sort of reversed configuration that Goldwater—again according to Goldwater—had apparently often found himself in. Known out West, he says, as “Broadway” because of his New York origins, he seemingly attracted the affections of at least two girls at the same time whenever he ventured out of the house.) In the comics, Archie complicated the reversal by not being able to make up his mind which of the girls he desired most.

Maybe, however, it was nothing like this. I asked around in various places to find out if any living witnesses could be found who recalled the creation of Archie and company. Journalist and comics connoisseur Jay Maeder kept my request in mind for a time and was able, eventually, to provide the following (all in italics):

Met a gent named Joe Edwards at a cartoonist function yesterday, and, as he turned out to be a very early MLJ guy who said he’d been around at Archie’s creation, I picked his brain a little. And he sez: One day he and Bob Montana were called in by John Goldwater and instructed to whip up something new, market-wise, something totally unlike all the costumed-superhero stuff flooding the stands. Whereupon he and Montana sat down and created Archie and the whole cast of characters. This was the entire sum and substance of Goldwater’s contribution. In short, Goldwater had nothing to do with it. Not only did he not specify an Archie-like character, he never even specified teenage humor. All he wanted was non-superhero.

RE the story Goldwater told me about his having hitchhiked around the country and gotten into some small-town trouble over the local Indian babes, this ostensibly being the genesis of Reggie: Edwards says he’s heard that story many, many times, and it’s a total crock. How self-serving Edwards’ own version might be, I can’t say. He didn’t seem to be a braggart or a blusterer (unlike JG, for example), and his Bails listing supports the career history he gave me. Anyway, for what it’s worth, here’s a primary-source reminiscence for ya. End of Maeder’s report.

RCH again: The Maeder-Edwards account fits somewhat with another Goldwater version (the one in which he was inspired by Superman to find something wholly different). And I’m inclined to believe Edwards on Jay’s recommendation. It’s possible to incorporate the Montana family contention into this version, too: although Edwards says he and Montana, in effect, jointly invented the Archie ensemble, he may not have known that Montana had been toying around with teenage characters for some years; so when the opportunity presented itself in conference with Edwards, Montana simply pulled his notions off the shelf in the back of his mind and offered them. It may have been Edwards (not Goldwater) who suggested dropping two of the teenage foursome that Montana had originally envisioned. In fact, perhaps we could safely substitute Edwards’ name for Goldwater’s throughout the narrative of Archie’s conception.

In the last analysis, I favor Edwards’ version because Goldwater’s seems so self-aggrandizing, so typical of a survivor: because no one can any longer contradict his assertions, the survivor, however marginal his actual participation in the events being turned into official archives, feels free to claim all sorts of achievements, thereby elevating his role in history. Highly suspicious. Maybe true, but still suspicious.

A fallacy lurks in favoring Edwards’ version of these events: since I’m already inclined to disbelieve Goldwater’s version, I’m likewise inclined to believe any credible alternative—in this case, Edwards’. In other words, I’m a sucker for anything that agrees with my own biases.

For an early Montana version of the creation of Archie, I turn to the May 1970 issue of Jud Hurd’s Cartoonist PROfiles. Interviewed by Hurd, Montana says: “John Goldwater came to me and said they’d like me to try and create a teenage strip. John thought of the name ‘Archie’ and together we worked it out. I created the characters and developed it.”

This interview undoubtedly took place well before the official version of Archie’s conception was formally adopted as a compromise between the Goldwaters and the Montanas (with Goldwater inventing the characters and Montana visualizing them), and while it fits, albeit somewhat awkwardly, into that formulation, Montana says quite unequivocally “I created the characters.” At the time of this interview, Montana was producing the Archie newspaper strip, but he was still working for Goldwater, and presumably anything he said had to conform, more-or-less, with whatever notions Goldwater was nurturing—hence, Goldwater names the character and “together we worked it out.” Still, “I created the characters and developed it” is a pretty straight-forward refutation of the official Goldwater claim. And it fits better—although scarcely perfectly—with what Edwards said.

I’m tempted to let Montana have the last words, but a few syllables need tweaking, so I’ll plunge further into the thicket.

By the mid-1950s, most teenagers in comics had faded away, leaving Archie as the nation’s perennial adolescent, and his high school adventures, laced with romantic frustration as well as simple juvenile pranksterism, embodied in popular culture a widely accepted notion of teenage life for generations thereafter. Montana left MLJ Comics in late 1942 for military service in World War II, and when he returned to civilian life in 1946, it was deemed time to introduced Archie to newspaper readers and Montana was given the job. While Montana was solely responsible for the newspaper comic strip version of Archie until his death in 1975, Goldwater continued to oversee the operation of Archie’s fate in an ever-lengthening list of teenage comic book titles from Archie Comics. He also doubtless perpetuated the myth that he was the principal creator of Archie.

A myth, comics historian (and editor of this site) Dan Nadel tells me, still alive and well at Archie. But the IDW publication lately of Archie: The Classic Newspaper Strips (1946-1948) “goes some way towards giving credit to Montana,” Nadel said, adding that the volume “shows Montana to be a better writer/artist than anyone thought.”

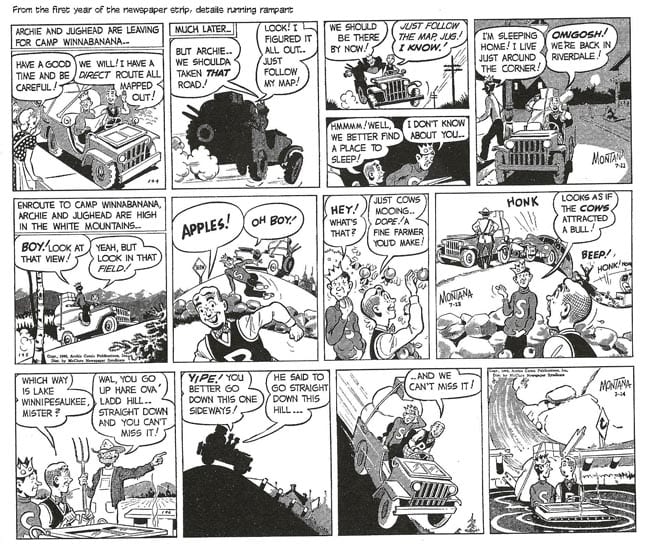

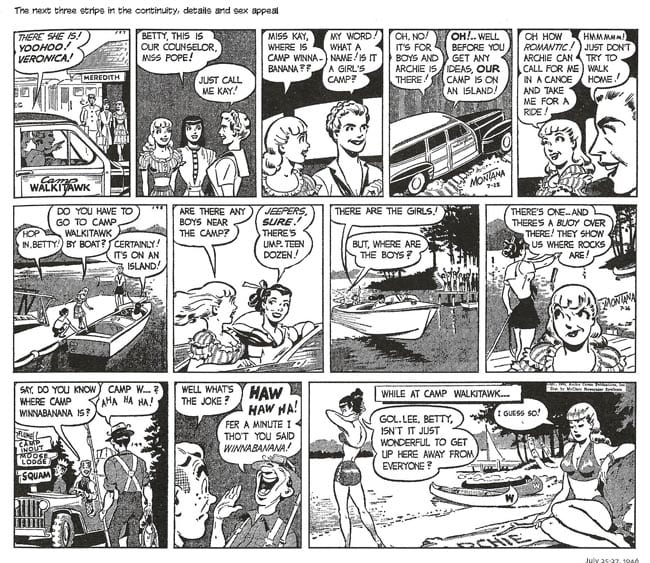

It’s possible that Montana was working with better writers on the strip than he’d been collaborating with earlier on the comic book Archie, but in the Cartoonist PROfiles interview, Montana says he’s working solo: “I do all of the writing of the daily and Sunday Archie strips,” he says, adding that he usually writes a week’s worth of dailies in one eight-to-noon morning session; the Sunday, on another morning. And with the dailies, Montana successfully produces the most challenging of the newspaper comic strip genre—humorous continuity in which an on-going story is punctuated every day with a punchline.

Visually, these first two years of Archie burst with energy: the characters are often depicted full-figure, and they seem constantly in motion. Greg Goldstein, the book’s editor, marvels that the strips seem “overstuffed with animated characters bursting at the panel edges—the antithesis of today’s simplistic ‘talking head’ approach to the gag strip.” I agree, but I don’t go as far as he does when he says the strips have a “kinetic energy that’s rarely been matched before or since in humor strips.” It would seem that Goldstein has never seen Gene Byrnes’ Reg’ler Fellers, for instance, or any of a dozen other pre-1950 humor strips that were rendered in an equally lively manner. Most comic strips, in fact, were better drawn in the years before post-World War II shrinkage set in, reducing the space available for any kind of drawing at all.

Montana, like many cartoonists who produce daily newspaper strips, employed an assistant who helped with the drawing. But it was Montana’s visual sensibility that shaped the strip. “It usually takes me from one to two days to pencil the six daily strips,” he told Hurd. “I pencil the Sunday page, as a rule, the same day that I write it. Next, I ink the heads or anything particularly important, and then send the stuff down to my assistant in Manchester. He inks the bodies, the backgrounds, etc., and delivers the finished strips to King Features.”

The recent revitalization at Archie Comics has indirectly, or directly, provoked a small flight of books about Archie. In addition to the IDW volume reprinting the first two years of the comic strip, Dark Horse has launched an archival series, beginning with Archie Firsts, a compilation of stories recording the first appearances of Archie (whose nickname is “Chic” in the first story), Jughead, Betty, Veronica, and Reggie, and continuing with volumes that reprint the comic book stories in sequence. Artists Dan DeCarlo, Stan Goldberg, Harry Lucey, and Samm Schwartz have each been spotlighted in collections of their Archie art. Archie stories are being packaged in book form at a furious rate—the best of the 1950s, 1960s, Christmas “classics,” and so on; the excitement threatens to go on forever. But Craig Yoe’s Archie: A Celebration of America’s Favorite Teenagers, is the best of this conspicuous spate.

Yoe begins with a short history of the founding of the company by Goldwater, Silberkleit, and Coyne, then provides brief biographies of the Archie characters, followed by essays about most of the principals involved in creating Archie stories—John Goldwater, Bob Montana, Harry Shorten, Victor Gorelick, and Dan DeCarlo and other artists (Bob Bolling, Harry Lucey, Samm Schwartz, Stan Goldberg, Dan Parent, Fernando Ruiz) and writers George Gladir, Frank Doyle, and Craig Boldman, concluding with Jon Goldwater and Nancy Silberkleit and Mike Pellerito, the trio responsible for the present rejuvenation of the company’s funnybooks.

Like all of the books Yoe has produced in the last few years, Celebration is a trove of rarities, a veritable feast of visual treasures—many never printed before—among them: from Close-Up magazine, a 5-page fumetti-style article showing how comic book characters are made (employing photos of various MLJ staffers at work), promotional brochures, paper dolls, fan club premiums, company Christmas cards, pages from calendars featuring the Archie characters, dozens of photos of various personages through the years, and, rarity of rarities, a previously unpublished story about Archie’s cousin Andy Andrews, an adventuring journalist up to his neck in Cold War espionage, drawn in a somewhat more realistic manner by Harry Lucey and reproduced from the original art. It also includes a few other complete stories from the Archie canon—Archie’s debut story from Pep, for instance.

Several of the biographies about Archie creators include interviews conducted by Yoe,and all of these essays, whether derived from ancient records or contemporary transcripts, are presented with exemplary journalistic objectivity. Taken together, they can be viewed as testimonies, often in the witness’s own words, offered as they stand without editorial adjustments or comment, regardless of the occasional contradictory assertion. Yoe lets us be the jury: based upon the testimonies before us, we get to decide who’s embellishing the truth and who isn’t. Goldwater and Montana each testify about the creation of Archie, and each essay shines a little new light on the dispute.

The Montana essay notes that Montana “visually modeled Archie after himself.” Quoting from an unpublished John Goldwater autobiography, Yoe supplies the whole creation myth from the publisher’s perspective, beginning with Goldwater’s “sketching” characters, displaying a heretofore unheralded drawing ability: “One day, while I was sketching, a face stared back at me. ‘Why are you so special?’ I asked the penciled drawing on my table in front of me. He reminded me of someone else, an old school friend named Archie. ... [who] used to commiserate with me all the time about the problems he had with girls because of their rivalries for his affection.” There we have it: Archie bursting full blown from Goldwater’s forehead.

On the other hand, the Montana essay is accompanied by copies of pages from Montana’s highschool diaries that depict a teenage youth in plaid pants, bow tie and saddle shoes, an ensemble that would materialize years later as Archie’s standard wardrobe.

Joe Edwards is not among those who rate a professional biography in the book, but he’s quoted in the Harry Shorten essay. Shorten was an editor at MLJ, and he conceived, wrote, or edited much of the line during the company’s early period “and was, in fact, the editor of Pep when Archie debuted.” Shorten’s “was the guiding editorial hand. Artist Joe Edwards told comics historian and Archie inker Jim Amash, ‘He was a very good editor. He made the guys feel very important. ... [He] was very instrumental [in the development of Archie] and kept it afloat. Let me put it this way: Harry was a good writer. He knew how to take a story and make it into a viable product.’ According to an anecdote passed down in Shorten’s family, Harry himself suggested the Betty-Veronica rivalry, inspired by his own daughters, one of whom had dark hair while the other was blonde.”

In the Harry Lucey essay, Yoe quotes Lucey’s daughter, Barbara Lucey Tancredi, who believes that Goldwater asked Montana and Lucey to create the new character when the two young men were sharing a studio on 14th Street on Union Square. “They met my mother and my Aunt Betty,” said she, “who both worked in a nearby building, in a restaurant in the area. Bob Montana dated my aunt and named the character Betty for her. Veronica was my father’s character—based on Veronica Lake with the pageboy haircut.”

Nothing in Yoe’s book settles anything about individual creatorship. Nor is it intended to. Everything in it, in fact, supports the notion, as Yoe says, that creating (and producing) Archie was (and is) a team effort, a collaborative enterprise. (Instant of revelation: I count Craig Yoe among my friends, so my opinions in this segment may be as suspect as they are on Goldwater, about whom I don’t feel very friendly—although he was undeniably a nice fella; how else would he keep all the friends he had?)

Despite all the competing versions about the conception of Archie—or, perhaps, because of them—Goldwater’s role has shrunk to considerably less than his claim to have invented Archie out of the whole cloth of his own life.

(Continued)