The dwindling pool of surviving Golden Age talent grew a little smaller last week with the passing on the afternoon of December 7th of Jerry Robinson, a famed comic book artist, political cartoonist, comics historian, curator of comics art shows, and passionate advocate for cartoonists’ rights.

The dwindling pool of surviving Golden Age talent grew a little smaller last week with the passing on the afternoon of December 7th of Jerry Robinson, a famed comic book artist, political cartoonist, comics historian, curator of comics art shows, and passionate advocate for cartoonists’ rights.

Robinson is perhaps most famous for his creation of the Joker while working as Bob Kane’s assistant during the early years of the Batman comic book. Robinson was Kane’s assistant and ghost for seven years, eventually graduating to penciling and inking the interior pages, as well as drawing some truly memorable covers. During his tenure on the strip, Robinson added much to the luster of the Batman legend, including coming up with the name Robin the Boy Wonder (inspired by Robin Hood), and designing his costume (inspired by the N.C. Wyeth painting Robin Meets Maid Marian). The addition of Robin to Batman’s continuity opened the floodgates of youthful superhero sidekicks in the 1940s, so if you’ve always loathed those characters, blame Jerry Robinson and Batman writer Bill Finger, who first suggested that Batman needed a sidekick. Additionally, Robinson helped Finger with the conception of Alfred Pennyworth, Bruce Wayne’s butler, and had a hand in creating Two-Face, one of the most intriguing and tortured of Batman’s rogues gallery of villains. To his dying day, Bob Kane always denied that Robinson came up with the Joker, but according to Kane’s first assistant and long-time ghost on Batman in the 1950s and '60s, Sheldon Moldoff, “(Bob Kane) was not one for sharing credit. He just couldn’t do it. It was not in his ego or his makeup…” Most of Kane’s other collaborators and assistants have echoed this sentiment.

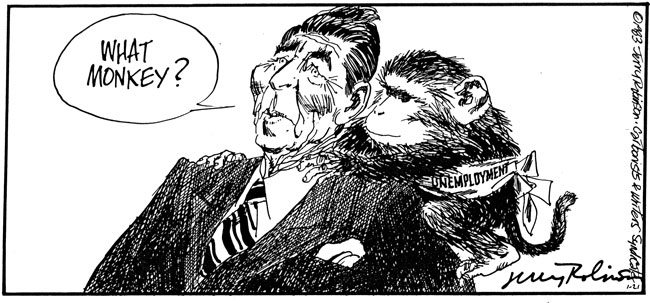

However, while working for Kane Robinson became an excellent cartoonist in his own right, drawing hundreds of pages of Batman continuity and crafting some of the most memorable Batman covers in history, especially those featuring the Joker. But after six years Robinson grew restless and he left Batman to chart his own path, going on to create “London”, a superhero spawned by news of the aerial “Blitz” carried out on Britain in the early days of World War II, and “Atoman”, one of the first superheroes of the Atomic Age. He also teamed up with his friend Mort Meskin, a talented and very troubled cartoonist, to make “The Black Terror” one of the best-looking superhero features in comic books. Robinson left comics in the early '50s to co-create (with writer Sheldon Stark) Jet Scott, a scientifically realistic and visually innovative science fiction daily and Sunday newspaper strip for The New York Herald Tribune. It premiered in 1953 and lasted for two years, predicting many of the astounding technological feats that would occur in the post-Sputnik era. The prolific Robinson continued to work as a newspaper cartoonist, creating the humor strip True Classroom Flubs and Fluffs, which ran for most of the 1960s in the New York Sunday News and was later incorporated into the Daily News. From the early '60s on, Robinson wrote and drew a strip called Still Life, in which inanimate objects made humorous and often very pointed social and political comments. His Life with Robinson strip ran from the early '60s through the early '80s and was widely respected.

In his professional capacity, Robinson served as the president of the National Cartoonists Society from 1967 to 1969 and later served a two-year term as president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists beginning in 1973. In 1978, Robinson established his own syndicate, Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate/Cartoon Arts International, the very first international cartooning syndicate, which now boasts 550 members from 75 countries worldwide. DC Comics announced that it had hired Robinson as a Creative Consultant in May of 1978, though his duties and responsibilities were not spelled out in the initial press release.

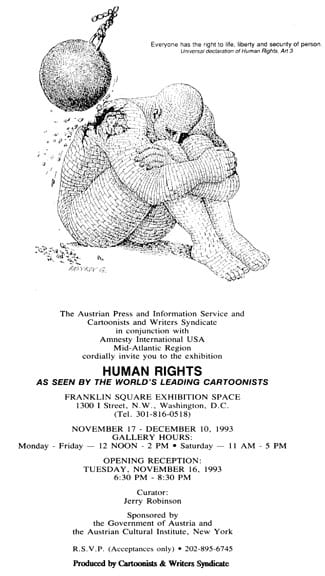

Even if he hadn’t been a first-rate artist and writer, Robinson would still be remembered for his role in popularizing comics as a genuine art form, both in his books, and as a tireless curator of gallery and museum shows of comics art. Robinson curated his first show of comic book art at the Graham Gallery in New York, which opened on April 4, 1972. This pioneering exhibit boasted 145 works by 120 artists, including Winsor McCay, Peter Arno, Jack Kirby, Milton Caniff, Heinrich Kley, James Thurber, Alex Raymond, Burne Hogarth, Sir John Tenniel, and Mort Meskin, to name only a few. It occupied two floors of the gallery, and encompassed many areas of cartooning: comic strips, magazine cartoons, caricature, political cartoons, and of course, comic books. This was only the first of many shows that Robinson would curate, including serving as the special consultant for exhibitions of cartoon art at The Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. He also curated exhibitions abroad, including the first American cartoon art shows in Tokyo, Warsaw, and Moscow, as well as numerous others in China, Portugal, Slovenia and the Ukraine. The United Nations invited Robinson to produced major exhibitions: In Rio de Janeiro for the Earth Summit in 1992; the Human Rights show in Vienna in 1993; the Population & Development show in 1994, staged in Cairo; and in 2007 the Sketching Human Rights show in New York City. The year 2004 found the seemingly unstoppable Robinson curating what is regarded as the first in-depth exhibition focused on the early artwork of the superhero genre, The Superhero: The Golden Age of Comic Books 1939 –1950 at the Breman Museum, Atlanta. Next, Robinson curated The Superhero: Good and Evil in American Comics, an exhibition which debuted at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2006.

Among the many honors heaped on Jerry Robinson during his lifetime were several National Cartoonists Society Awards including the following: one in the Comic Book Division in 1956 (for his work on Batman), one for Still Life as Best Newspaper Panel Cartoon in 1963, a Special Features Award for Flubs and Fluffs in 1965, and the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award (2000). Robinson was also nominated by the NCS six times in the category Best in his Class. He was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2004, and was awarded the Sparky Award for Lifetime Achievement at last year's San Diego Comic-Con International. His Life with Robinson political cartoon was also honored overseas by the International Salon of Humor in Italy and the Overseas Press Club, which recognized it as the Best Cartoon on Foreign Affairs. The International Humor Pavilion in Montreal, Canada named him a Distinguished Foreign Cartoonist, while the world-famous Lucca Exposition of Comics bestowed upon him, the Premio Gran Guinigi. He was also received cartooning awards in Turkey, Russia, and China, and was given the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award, the Dick Giordano Humanitarian Award, a San Diego Comic-Con Inkpot Award, and the Nemo Award from the Toonseum in Pittsburgh.

Jerry Robinson wrote or edited at least thirty books, including a number of well-regarded books on the history of the comics medium, the encyclopedic and well-researched volume The Comics: An Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art (1974), which was reissued in an updated and expanded edition by Dark Horse in 2011, Skippy and Percy Crosby (1978), plus three paperbacks collecting his True Classroom Flubs and Fluffs, The World’s Greatest Comic Book Quiz, and a two-volume Jet Scott collection also from Dark Horse. In addition, Robinson illustrated biographies of Lou Gehrig, Jim Bowie, Abraham Lincoln, and provided illustrations for books on space flight, logging, civics, and atomic energy. Robinson’s talent was nothing if not wide-ranging.

He also loved comic art in a very personal way, too, rescuing countless pieces of comic book art from trash bins and incinerators, thereby saving these priceless pieces of our cultural heritage from oblivion. When I interviewed Robinson in the mid-'80s for a three-part interview that ran in Comics Interview, he related the story of how he and a friend happened to be passing the King Features offices, where workmen were consigning Hal Foster Tarzan pages to the incinerator. Robinson managed to save about 20 or so. He brought them back to his studio and gave most of them away to colleagues, though he wisely retained a few for his own personal collection of comic art, some of which was displayed for years on the walls of his lovely Riverside Drive apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

In the late '70s he again became a hero to America’s comic book fans for his championing (along with artist/activist Neal Adams) of the cause of Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Siegel and Shuster had sold their creation in 1938 for the paltry sum of $130 and then watched as DC Comics made millions on the character from comic books, books, toys, radio, TV, motion pictures, and other spinoff products while they lived in poverty and obscurity. By making a series of phone calls to the offices of DC Comics, Robinson was instrumental in helping Siegel and Shuster to finally win their lengthy legal battle with DC Comics and Warner, its corporate owner, when they were finally awarded annual payments, health insurance, and published credit on the strip they had created so many decades before. This was not the only time Jerry Robinson put himself on the line for fellow cartoonists. In 1980, he interceded on behalf of Francisco Laurenzo Pons, who had been thrown into prison for cartoons lampooning the repressive military dictatorship of Uruguay. Robinson also smuggled money into the Soviet Union to help poverty-stricken Russian cartoonists whose work was being suppressed by the Soviet government. As creative and talented as he was, Jerry Robinson was much more than a man of the arts. He was a man of courage who lived out his ideals in his day-to-day life, working to protect the rights of cartoonists world-wide, and make their lives better.

More than almost any other figure from comics’ Golden Age, Jerry Robinson will be greatly missed for his enormous talent, his scholarship of the comics medium, and the greatness of his character. Jerry Robinson is survived by Gro, his wife of 57 years, his son Jens, a daughter, Liv Robinson-White, and two grandchildren.

Further reading on TCJ.com: Gary Groth's definitive interview with Robinson.