“I always wanted to be a cartoonist.”—Jack Davis

The longtime cartoonist and illustrator Jack Davis died on Wednesday at the age of 91.

Jack Davis was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on December 2, 1924. By his own account, he had an idyllic childhood. Both parents —as well as his school teachers— encouraged Jack’s artistic inclinations. Apart from drawing —“Only thing I can do is draw”— he was uninterested in and bored by academic pursuits. But he excelled at the High Museum of Art School. The school taught drawing from life and Davis found this enormously helpful — and invigorating, both aesthetically and experientially.

Davis was drafted into the Navy upon graduation from high school in 1943. Once his superiors learned of his artistic skills, he was conscripted to draw several comic strips for the Gosport Weekly, the base newspaper.

His University of Georgia years were a whirlwind of extracurricular drawing activity and self-marketing, presaging a career of almost unparalleled productivity. He studied both oil and portrait painting and art history under Lamar Dodd, an artist and activist.

Eventually Davis landed a gig as an assistant to Ed Dodd (Lamar Dodd’s cousin) on the recently launched Mark Trail comic strip. This proved to be his biggest step professionally. Dodd suggested that Davis move to New York City and attend the Art Student’s League. “You’re good,” Davis says Dodd told him, “you gotta go to New York.”

Davis would, of course, move to New York, but not before falling in love with the woman he would soon marry.

Dina Roquemore and Jack Davis attended the same grammar school and high school, but they met each other for the first time at the University in their freshman year (although Davis was several years her senior due to his stint in the military). They met at the campus swimming pool. “She had a beautiful figure and I guess I was smitten with that,” says Davis with typically Southern gentlemanly reserve. “But I tell you, coming out of the Navy, after being in three years, not seeing anything but a Wave once in a while…that was something else. I mean, that was beautiful. On campus there were some pretty, pretty girls, and Dina was one of them.” They didn’t have any money to speak of, so their dates consisted of going to the movies and seeing each other on campus. The courtship lasted close to three years.

Davis decided to take Ed Dodd’s advice and try his luck in New York City. He had been accepted into the Art Students League, so he began attending classes at night and looking for freelance jobs during the day. He had a blue suit and a tailor-made pair of Cordovan wing-tip shoes, and, armed with a small portfolio of watercolors, Civil War drawings, and strips he’d drawn for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, began pounding the pavement, going to every syndicate and advertising agency he could find (he walked up and down Madison Avenue so much, he says, that he got an in-grown toe-nail.) He had no luck.

But, the Art Students League posted job notices on its bulletin board and he noticed one day that the cartoonist Mike Roy was looking for an assistant to help him draw The Saint newspaper strip. (The Saint was a thief-turned-detective, who had, by 1949, become a commercial fixture in pop culture, appearing in novels, movies, and comics. The strip was written by Leslie Charteris, who wrote the first Saint novel, Meet The Tiger, in 1928.) Davis went to the New York Herald Tribune, who was syndicating the strip, applied for the job and got it. (Coincidentally, the Herald Tribune ran a strip he previous year titled Silver Linings by someone who would play an important role in Davis’s lie — Harvey Kurtzman.) Roy worked on Long Island and would mail the original art to Davis, who would finish the backgrounds. He was paid $100.00 week, a steady income he welcomed since he had gotten engaged to Dina Roquemore while he was in New York and planned on marrying her the following year.

He spent a year working on The Saint and attending the Art Students League at night. He took several classes drawing live models, but otherwise, Davis, says he learned very little that improved his drawing or technique. “There were just a lot of veterans there that couldn’t draw,” he said. “They were probably taking advantage of the GI Bill.” When asked directly what he learned at the Art Students League, Davis said: “I learned to exist. …Just the experience…I met some guys who were kind like the Dead End Kids, but they were just great guys who were walking the streets of New York. That was their hometown.”

Davis’s stint on The Saint ended in late 1950. He began making the rounds again and decided to add comic book companies to his list of potential clients. The 2nd or 3rd comics publisher Davis visited was a company he’d had no familiarity with, indeed never heard of — Entertaining Comics. Davis walked out the door with a script to draw. Davis didn’t know it at the time, but, as so often in his career, he was at the right place at the right time —he was about to become a star in one of the greatest constellations of artists ever assembled by a mass market comics publisher.

This was a heady time for Davis because not only had he stumbled onto the best comics publisher of the period, but he was bout to wed.

Jack Davis and Dina Roqumore married on October 22, 1950 in Atlanta, and spent their honeymoon at the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. Davis would liked to have lived in the city for another year or so, but the rent was too expensive, so they moved out of Manhattan and into an “itty-bitty apartment over the railroad tracks” in Eastchester, New York, just outside Scarsdale, in early 1951. He and Dina would often drive his completed pages into the EC offices: “My wife would erase the pencils before I got to Lafayette Street.”

Feldstein used Davis for all three of his horror titles — Vault of Horror, Tales from the Crypt, and Haunt of Fear. He was one of the most effective artists who drew horror stories at EC —and one of the most prolific; turning out more than 500 pages in less than five years.

Feldstein used Davis for all three of his horror titles — Vault of Horror, Tales from the Crypt, and Haunt of Fear. He was one of the most effective artists who drew horror stories at EC —and one of the most prolific; turning out more than 500 pages in less than five years.

While the young artists that Gaines recruited to draw were continuing to improve their craft year by year, his comics, particularly the horror titles, were running afoul of the poisonously censorious political climate of the 1950s. There was, coincident with EC’s glorious rise, a growing backlash against comics, fueled by alarmist newspaper columnists, magazine writers, and Dr. Fredric Wertham’s notorious book, Seduction of the Innocent, that purportedly “proved” that comic books caused juvenile delinquency. The strict guidelines of the Code effectively put EC’s horror line out of business.

While the young artists that Gaines recruited to draw were continuing to improve their craft year by year, his comics, particularly the horror titles, were running afoul of the poisonously censorious political climate of the 1950s. There was, coincident with EC’s glorious rise, a growing backlash against comics, fueled by alarmist newspaper columnists, magazine writers, and Dr. Fredric Wertham’s notorious book, Seduction of the Innocent, that purportedly “proved” that comic books caused juvenile delinquency. The strict guidelines of the Code effectively put EC’s horror line out of business.

Luckily, EC was publishing Mad.

Luckily, EC was publishing Mad.

Harvey Kurtzman conceived of Mad in 1952 (the first issue debuted in August). Kurtzman edited, wrote, and laid out its comics pages, just as he was doing concurrently with his two war titles. He did no drawing in Mad, but he enlisted the artists at EC most adept at humor: Will Elder, Wally Wood, John Severin, and, of course, Jack Davis. Davis was among the most versatile artists at EC, equally good at drama and humor, and capable of illustrating every genre — mystery, horror, war, Western. (Science fiction may have been the only genre at which he did not excel.)

Davis remembers the conception of Mad: “We got together and figured out that Harvard had the Lampoon, and you had different magazines: Esquire had “Esky,” and we sat around and thought up Alfred E. Neuman.” Davis appeared in every issue of the 23 comic book Mads except #s 7 and 22. Kurtzman never liked the comic book format, feeling it was shoddy and low-rent, so when the EC line began failing in 1955, Kurtzman used the opportunity to demand that Gaines turning Mad into a magazine — under threat of quitting. Gaines complied; with the 24th issue, Mad moved from a monthly 10 cent comic to a bi-monthly 25 cent magazine. Davis continued working for the magazine format Mad, but six issues later, Kurtzman quit the magazine —his last issue was #28, July 1956— accepting an offer from Hugh Hefner to edit a much slicker humor magazine with a bigger budget — Trump.

Kurtzman asked Davis to join him at Trump. Davis’s allegiances were torn. But, he made his decision and he went with Kurtzman to Trump. Unfortunately for Davis and all the other creators Kurtzman assembled Trump lasted only two issues due to financial reversals in the magazine publishing industry.

Thus was born Humbug, a new satirical magazine, financed —and owned— by the artists themselves, and edited, again, by Kurtzman. The artists were Kurtzman, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder — and Jack Davis. All the artists invested in the magazine except Davis who either didn’t have the resources to or wasn’t comfortable investing what little he had. (The fact that Davis’s son Jack III, born in 1954, was three years old, may have made him more attentive to his financial responsibilities.) The other artists agreed that Davis was absolutely essential to the enterprise, and offered him equal ownership and a monthly stipend. The first issue of Humbug debuted in June, 1957, but, this magazine, too, was another noble failure —it lasted 11 glorious issues in which Davis did some of the best comic illustration of his career.

Thus was born Humbug, a new satirical magazine, financed —and owned— by the artists themselves, and edited, again, by Kurtzman. The artists were Kurtzman, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder — and Jack Davis. All the artists invested in the magazine except Davis who either didn’t have the resources to or wasn’t comfortable investing what little he had. (The fact that Davis’s son Jack III, born in 1954, was three years old, may have made him more attentive to his financial responsibilities.) The other artists agreed that Davis was absolutely essential to the enterprise, and offered him equal ownership and a monthly stipend. The first issue of Humbug debuted in June, 1957, but, this magazine, too, was another noble failure —it lasted 11 glorious issues in which Davis did some of the best comic illustration of his career.

In 1960, Harvey Kurtzman created Help!, his third —and last— humor magazine in partnership with Warren Publishing, an independent outfit owned by Jim Warren. Davis appeared in only a couple issues (possibly because Help!’s budget was relatively minuscule and Kurtzman couldn’t pay Davis what the artist was capable of getting almost anywhere else).

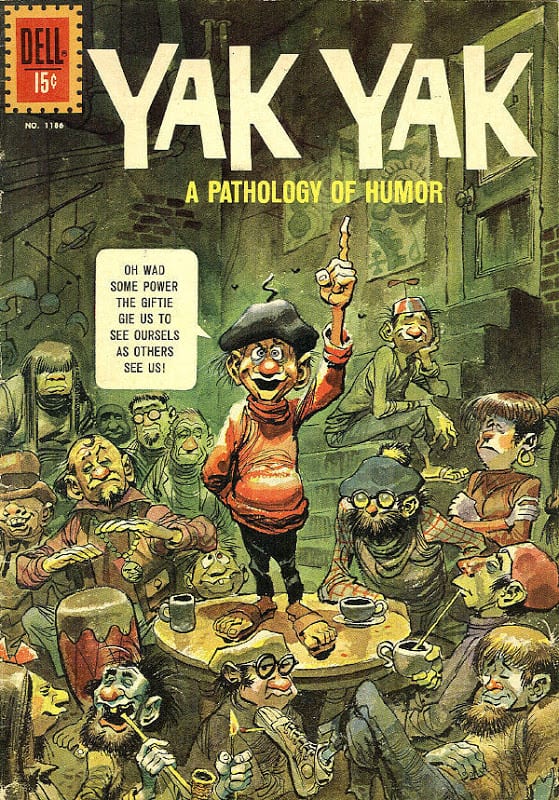

Davis was commissioned by Dell Comics to conceive, write, and draw a humor comic titled Yak Yak, two issues of which were published in 1961 and 1962. According to Davis, they asked him to do it because of his work on Mad —still paying commercial dividends a half a decade after he stopped working for the magazine. “Dell wanted their own Mad, so they approached me to write it and draw it. They sort of gave me my head.” The humor was essentially Mad-lite and Davis admits that he “struggled with it. I’d rather have somebody write for me or tell me what to do. I tried and failed.” Nonetheless, he turned out over 60 competent pages of humor comics.

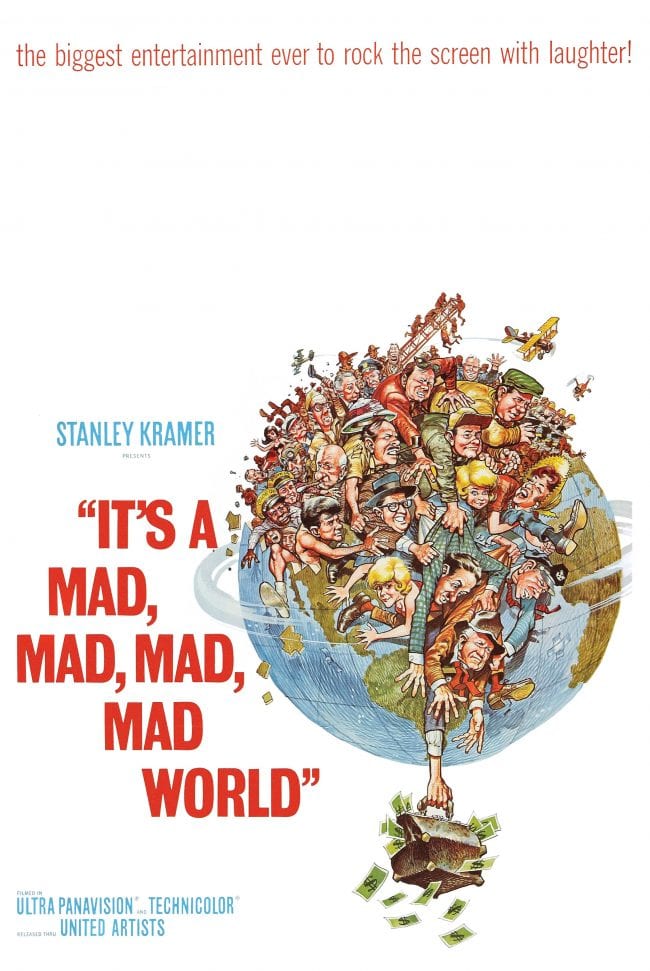

1964 and 1965 were breakthrough years for Davis. He drew the movie posters for Stanley Kramer’s highly successful 1964 comedy extravaganza, It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World. It was a tour de force of caricature and advertising efficaciousness and propelled Davis into the forefront of American commercial artists.

Professionally, Davis’s comics work was mostly behind him at this point with one exception: In 1965, he returned to Mad, and continued to work for the magazine into the 1980s.

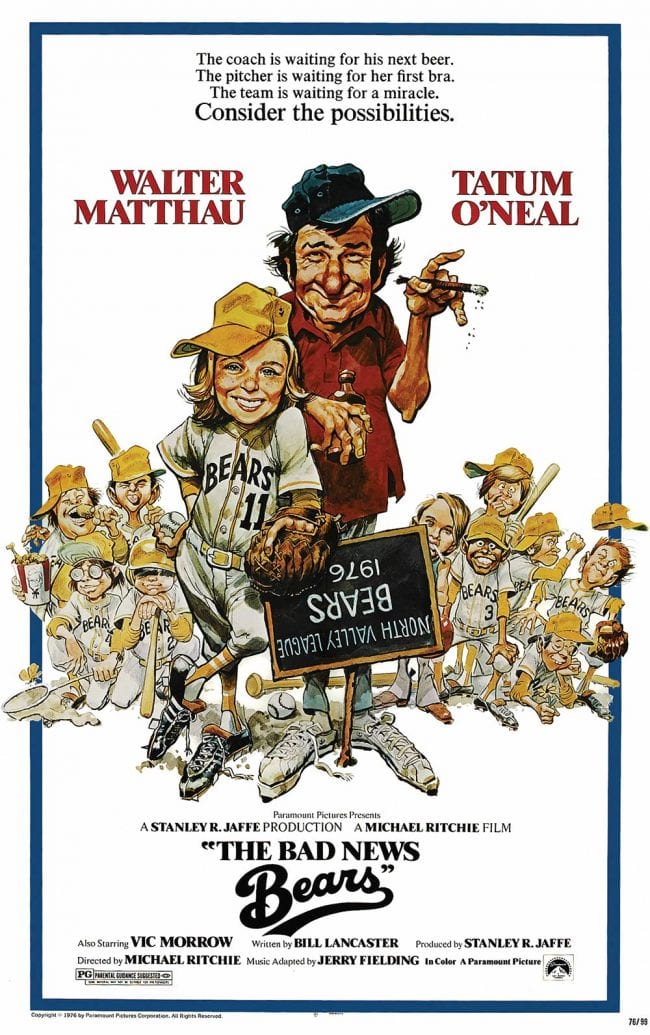

In rapid succession, Davis began contributing to the highest circulation mass magazines of the time: TV Guide, Esquire, Life, and his biggest coup — Time, for whom he did at least 26 covers from 1972 to 1976. Davis would, between 1964 and 1980, draw over 35 movie posters.

Davis continued to produce work at a prodigious pace. He never had a character with which a mass audience could identify him —a Charlie Brown, a Calvin or Hobbes— but his drawing style itself may have been the most recognizable of any cartoonist or caricaturist in the world.

Davis continued to produce work at a prodigious pace. He never had a character with which a mass audience could identify him —a Charlie Brown, a Calvin or Hobbes— but his drawing style itself may have been the most recognizable of any cartoonist or caricaturist in the world.

In 1988, he moved back to his beloved Georgia and finally started working at a more leisurely pace. He announced his retirement in 2014. His son, Jack III, an architect, designed his home on St. Simon’s Island next to the Frederic River. He lives near his son and his daughter Katie, who is an interior decorator, and whose husband owns The Hilltop Grille in Athens, in which a mural Davis painted is prominently displayed.

Looking over his long career, he said, “You live your life and just to leave something behind is so great. And I feel that I’ve had a great, great life.”

Davis is survived by his wife, Dena, his son, Jack Davis III, his daughter, Katie Lloyd, and two grandchildren.