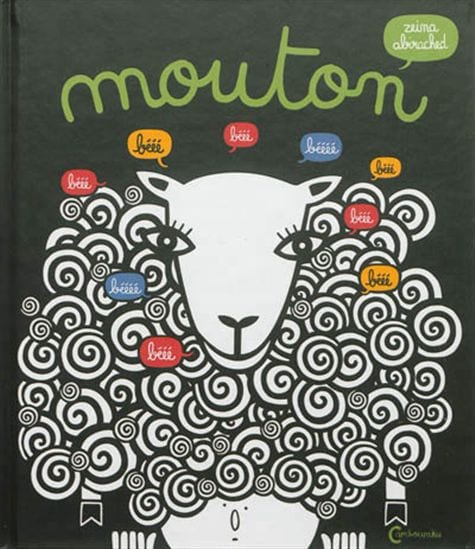

Cartoonist and animator Zeina Abirached was born in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War and in her book A Game for Swallows, she brings the conflict to life. From the perspective of a child, framed by a single night of bombing, she gives a sense of what it was like. She’s produced other work over the years. Her short animated film, which she turned into a children’s book published last year in France is “Mouton”–literally “sheep”–in this case referring to her curly hair. It’s a very personal book, but one that’s also universal. A Game for Swallows tells a less universal experience, but Abirached manages to ground it in the quotidian details in a way that makes it easy to find it an uneasy mirror of our own lives.

Cartoonist and animator Zeina Abirached was born in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War and in her book A Game for Swallows, she brings the conflict to life. From the perspective of a child, framed by a single night of bombing, she gives a sense of what it was like. She’s produced other work over the years. Her short animated film, which she turned into a children’s book published last year in France is “Mouton”–literally “sheep”–in this case referring to her curly hair. It’s a very personal book, but one that’s also universal. A Game for Swallows tells a less universal experience, but Abirached manages to ground it in the quotidian details in a way that makes it easy to find it an uneasy mirror of our own lives.

A Game for Swallows was translated by Edward Gauvin and published by Graphic Universe last year after being a critical and commercial success in France. The book–like all of Abirached’s work–shows the influence of David B., but Arabic calligraphy and its philosophy are at the heart of her approach. It is a beautifully constructed story in every sense.

Alex Dueben: Often when I’ll do an interview I’ll ask the artist to give some background information about the setting of their book, but I know that we could be here for a day or two talking about the origins of the Lebanese civil war. You were born during the war; what is your earliest memory of it?

Zeina Abirached: I have a very striking memory of the first time I crossed the green line and went to West Beirut (It is not my earliest memory of the war, but it was an experience that helped me to become aware of a lot of things).

It was in the early nineties, at the end of the war, at the time the war was essentially in the eastern part of Beirut where I used to live. I remember we had to leave our flat in a hurry and run away in our car to a more secure place. My parents decided to go to West Beirut for a while to be safe and make plans. I remember that the first things I saw in that part of my town I didn’t know yet–I was ten years old–was people in the streets, lights, animation, and the calm Mediterranean sea.

I felt like I was in a foreign country. I just couldn’t understand I was still in Beirut! I remember the first two days I couldn’t speak Arabic or French–which are my two mother tongues–I could only use the only foreign language I knew at that time: English.

You grew up and studied in Lebanon before you moved to France. What were your influences and your early exposure to comics and art?

You grew up and studied in Lebanon before you moved to France. What were your influences and your early exposure to comics and art?

We do not have a comics tradition in Lebanon, and in all the Middle-East. All my comics readings were essentially mostly French, Belgian and American.

When I was a child my parents had a lot of Franco-Belgian comic books at home I used to read a lot. We had a lot of time to read during war! I realize now I learned to read French by trying to decipher the words of Tintin, Asterix, Gaston and Lucky Luke. Later, I discovered, in the only comicbook store we had in Beirut in the late 90‘s–unfortunately it doesn’t exist anymore, as you may now Beirut is in constant mutation and the bookstore is now a trendy cafe–the books of David B., Tardi, Gotlib, Dupuy and Berberian, Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Munoz, etc.

When you decided to tell a story of the civil war, did you know that it had to be your story and your family’s story as opposed to a fictionalized tale?

When you decided to tell a story of the civil war, did you know that it had to be your story and your family’s story as opposed to a fictionalized tale?

I think I started writing comic books because I had the urgent need to tell our story. I grew up during a civil war in a country where we didn’t come to terms with our past. For example, until now, the program in history books at schools stops in the nineteen-sixties. We still don’t have an official version of the civil war.

After the war we practically did as nothing happened. The reconstruction of the city did its best to erase every track of the civil war and install a type of amnesty. Ten years after the end of the war I realized I had the urge to say, “It happened!” So I started to write some things I still remembered and to draw Beirut–the Beirut of my childhood that was slowly disappearing–and somehow realized I was writing a comic book.

How did you come to decide on the structure of the book? While there are details about what life was like, how the city was divided, etc., the book takes place in a single night.

The civil war lasted fifteen years. I needed to find a way to condense those fifteen years. I wanted the story to take place inside our apartment, in one particular room, as I started writing, I realized I was writing a “huis clos” [Note: In French the phrase translates to “in camera” and refers to something in private or behind closed doors] and I thought it would be interesting to have unity of time, place and action like for the classical theatre.

I also wanted my story to have a universal dimension. It takes place in Beirut in one particular apartment in one particular night, but it could be anywhere, anytime.

How much is the book a product of memory and how much a product of research?

I did a lot of research before I started to write A Game for Swallows. One day I came across a television documentary made in Beirut in 1984. A woman whose home had been hit by the bombings spoke a single, startling sentence: “you know, I think maybe we’re still more or less safe here.” That woman was my grandmother! I talked a lot with her, with my parents and my neighbours to compare my memories with theirs. But my connecting thread was my memories and the feelings I had when I was a child.

There’s a great map of your neighborhood and how close you grew up by your grandparents, and how dangerous it was to go there, but I’m curious what your sense of the city of Beirut was like when you were a child? Because the book does present a sense of being cocooned or trapped, visually through the imagery you use.

There’s a great map of your neighborhood and how close you grew up by your grandparents, and how dangerous it was to go there, but I’m curious what your sense of the city of Beirut was like when you were a child? Because the book does present a sense of being cocooned or trapped, visually through the imagery you use.

During the civil war, my street–Youssef Semaani street–was blocked by a wall made of sandbags in order to protect us from the sniper who was from the other side of the demarcation line.

When I was a child I thought that my street was a dead-end street. I was convinced that Beirut stopped at that wall.

I think the most repeated comment and useless comment made in reviews of your book is to compare you stylistically to Marjane Satrapi, but you both have similar influences like David B. What are those influences on your style and what are the influences on this book specifically?

It is always difficult to be conscious of the influences we have. Apart from David B.’s work, I remember I thought a lot of Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle when I began drawing A Game for Swallows–the importance of the sound in his movie, for example. I also am very interested in Arabic calligraphy, especially in the interplay of vacuity and presence in the way black fonts stand out against white background.

Beirut has changed a lot just in your lifetime. At the same time–and I say this as someone who has spent months not years in the Middle East–I get the sense that a lot of cities there have been transformed over the past twenty-thirty years and that so many neighborhoods and cities today are almost foreign to people of our parents’ generation. Do you have a sense of whether or how Beirut's changes differ from elsewhere?

Beirut has changed a lot just in your lifetime. At the same time–and I say this as someone who has spent months not years in the Middle East–I get the sense that a lot of cities there have been transformed over the past twenty-thirty years and that so many neighborhoods and cities today are almost foreign to people of our parents’ generation. Do you have a sense of whether or how Beirut's changes differ from elsewhere?

You are right, it is a question I frequently asked myself. I guess Beirut’s transformation may be more evident because of the destruction and the “tabula rasa” our politicians chose to install when we started re-building the center of the city. We lost our Old City–I mean the ancient city that belonged to the Lebanese people and to our collective memory–and we inherited a “New-Old-City” that doesn’t belong to anyone apart from Lebanese and foreign investors.

I feel like we are trying to rebuild our sense of belonging with the new landmarks we have. I guess this takes time, maybe many generations.

Talk a little if you would about how you thought of the final pages, the transformation of your name into a boat, because it really was a beautiful and graceful way to end the story.

The book ends with a run out of the secure cocoon I described in the book. I wanted to change the pace of the story. The cocoon breaks up, and I stop using panels to spread the drawing in the entire page.

The exit from the apartment is also the moment when I grow up. When I understand what was happening outside. It is the end of the age of innocence. I learn to write and my writing becomes a drawing. My name becomes the drawing of a boat heading by itself through its future.

What has the response to the book been like? I know that you were a part of the Hay Festival in Beirut last summer.

The book was received with enthusiasm! it has been translated into nine languages–but still not in Arabic, so in Lebanon it is read in French or English–and a Lebanese school-book publisher published it in French with a leaflet of exercises to do in class. I guess it is a nice way to introduce the discussion about our history at school.

What is the comics scene like in the Middle East? I feel like recently there’s been many more artists and publications coming out the region but I don’t have a sense of things more than a few years old.

What is the comics scene like in the Middle East? I feel like recently there’s been many more artists and publications coming out the region but I don’t have a sense of things more than a few years old.

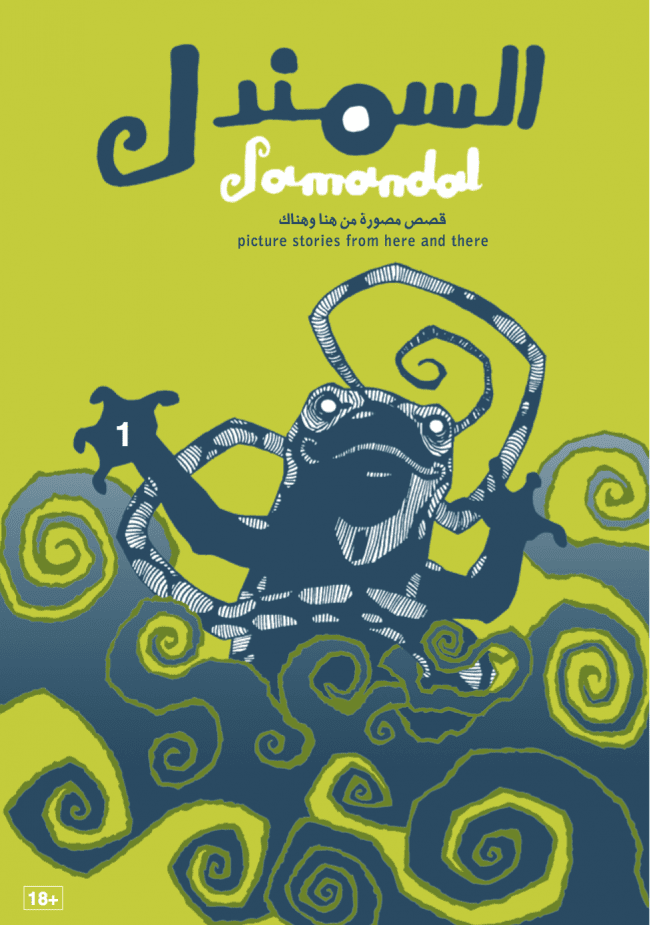

We have a comic magazine called Samandal which publishes stories in Arabic, English and French and another one called La furie des Glandeurs which publishes stories in French. Many young Lebanese artists are published for the first time in these two magazines, and they are important because they may help evolve the reading habits in Lebanon, but we still don’t have a comic publisher.