Shing Yin Khor is a cartoonist, game designer, and installation artist. They won the Ignatz Award for their minicomic Say it With Noodles in 2018, and their graphic memoir The American Dream? was one of NPR’s best books of 2019. Khor’s new middle grade graphic novel The Legend of Auntie Po tells the story of a young woman named Mei who works with her father as a cook at an American logging camp during the late 1800s. In this interview, Khor speaks about the influence of nature on their work, researching tools and architecture from a century ago, and writing about death for a young audience.

Tiffany Babb: I first came across your work as short comics and illustrations. Can you talk about how you began to create short comics?

Shing Yin Khor: I was a comics dilettante for a long time before I was a comics professional. Comics was a fun hobby, but also one of the things that just felt truest to how I’m naturally led to tell stories. I think I got into making comics the same way most of us do these days. I put up short things on the internet to amuse myself and my friends, and eventually I submitted to some websites and anthologies, and at some point you look back on a decade of work and realize that wow, you’ve been making comics for a while now.

You spend a lot of time focusing on nature in your work. Can you talk to me about your experiences with nature and how nature influences your work?

Weirdly, I think I have a bit of an antagonistic relationship to nature because it is always trying to kill me. But maybe that’s why I find it compelling. It’s hard to take something for granted when it is busy enveloping your state in wildfires and sending out tiny bugs to drink your blood.

But I think that relationship is also true for anyone that is connected to nature - it is a feeling of awe and irritation and helplessness and fear and grandeur and all encompassing beauty. It is clear to me that we have to be stewards of nature, that we have to be conscious of what we do to and with it, but it is also clear to me that nature is far more resilient than man is, and it is out of our own self interest that we should care about how we’ve fucked up our climate, because we are going to die first.

I think the nature experience that most influenced my work were the nights I spent alone in the backcountry of the Petrified Forest National Park while I was an Artist in Residence there. I would walk out into the desert in the late evening with just my backpack and water (the Petrified Forest backcountry is especially special because there is a visitor center on top of the ridge you begin from, so you can almost always see it and it would take some effort to get lost). I slept outside under the stars, and I knew I was the only human for a mile in one direction, and twenty seven miles in the other direction. I think that experience shaped my work because it made me so interested in the tension between human and nature, the things we get to think about when we are not surrounded by other people, the smallness of humans in the vastness of the nature space that can surround us.

One thing that stands out to me about your work is the way you lean into the fantastic and extraordinary. What does it mean to add the larger than life to the world we normally see?

I’ve actually never thought about this before! I feel like I was raised steeped in the intersection of fantasy and the real world because of all the books I specifically imprinted on - books like Gnomes (Huygen and Poortvielt) and Lady Cottington’s Pressed Faerie Book (Brian Froud), and the Griffin and Sabine (Nick Bantock) series - those are all books that sit in this very comfortable space of lending magic and weirdness to our existing world that aren’t interested in creating entirely new worlds, just focusing on the unseen and adding this additional layer of otherworldliness to our own experiences. I think a lot of my work leans to that lineage, it is both very much rooted in what we can actually see and touch, but also what we simply might not have noticed.

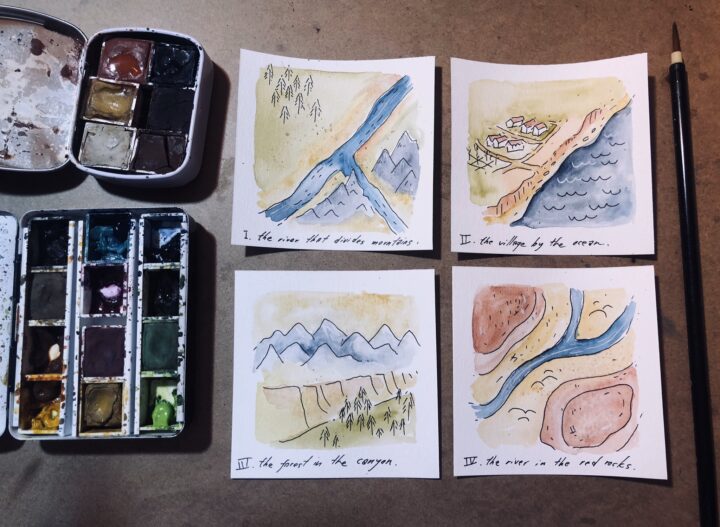

I particularly enjoy the maps you draw. The Legend of Auntie Po has a map at its beginning too. What interests you about maps and world building?

I think my brain is actually more practical than poetic. I like maps, infographics, things that explicate and categorize and convey information clearly and concisely. And I think that as storytelling mechanisms, they establish place and geography much clearer than exposition can, but I also think they lend a certain scale to a story, whether it is a grand scale like Tolkien’s world maps or just a logging camp as in my book. They establish that “yes, this story is going to take place here, specifically” even if that space never really expands past the boundaries of a logging camp.

I don’t think I think about worldbuilding quite as much as I just do it. I have a natural curiosity for the way people choose to live and the things they build and the rituals and traditions they embrace, and that feels like a natural compulsion towards worldbuilding, because you can’t be interested in those things without it.

Tradition seems to be a strong thorough line The Legend of Auntie Po, whether it is the tradition of telling tall tales or pushing to have a traditional New Year feast. Can you tell me about your interest in rituals?

I am interested in how humans try to understand the world they exist in, and I think tradition and ritual is a constant in that attempt at understanding. I think that humans are naturally led to categorize things and to do things that help them to understand the world around them, and ritual is one of those things that help us cope with our universes. I use the term “ritual” very generally - I don’t just mean city parades or church services, I also mean our personal rituals, like morning affirmations in the mirror, or having a favorite coffee mug, or preferring to tie our shoelaces a certain way. In my book, ritual spans from tall tales and funerary rites to just the girls always saving pie for each other.

The Legend of Auntie Po is based in a historical setting and you include facts about logging throughout. Can you tell me about your research process for this book?

Researching tools and architecture was pretty straightforward - there is a fair amount of pictorial documentation of this era of buildings and objects. I was an artist in residence at Homestead National Monument in Nebraska (which is on the first plot of land homesteaded under the Homestead Act) a few years ago, and many of the kitchen tools and other tools are drawn from reference sketches I made while I was there. I read an entire book about building a log cabin, but I am unclear if it actually helped me draw them.

The same can’t really be said about people. Personal working class Chinese histories from this era are not documented well at all. We have extremely few letters, largely from merchants and Chinese businesspeople, but mostly just census records, many of which do not correspond to a traceable individual. We do have a reasonable archeological record of what working class Chinese people used and left behind. That’s how we know that Chinese workers often had porcelain bowls and used chopsticks and had access to imported Chinese goods through merchants working in Chinatowns. We have some photographs, which is how we know that some of them wore more Chinese clothing, while many more would wear western styles.

A lot of these histories are glossed over in the popular American narrative. The popular conception of early American history, and especially that of Old West heroism is one full of white heroes and white individualism, which is more a matter of myth-building than historical fact. Often, marginalized groups are spoken of as a monolith, as a people rather than a collection of individual people, living a diversity of lives. This is not true now, and it wasn’t then either.

Auntie Po features characters who care about each other, but don’t necessarily fully understand each other, especially on subjects regarding privilege. What was important to you in setting up character dynamics like the ones between Mister Andersen and Mei’s father or between Mei and Bee?

I think people who do not often experience prejudice or a lack of privilege tend to write it in very distinct ways - where racism is like an on-off switch, where you can learn to be not racist because you have a friend who isn’t white. But in my life, and the life of many marginalized people navigating white-adjacency, most conflicts of privilege are not explosive. They don’t come to a boiling point. They remain simmering and awkward and subtly resentful, and I think this dynamic ended up in the book a lot.

Ultimately, this is a book about navigating whiteness - not necessarily an intentionally malicious whiteness, but just the simple ways that when you grow up in a society built to coddle whiteness, it becomes something that every non-white person learns to navigate in different ways. In the book, the vast majority of white characters in this book really do mean well. But there is a vast chasm between having good intentions and acting in solidarity with the marginalized people in your life. There are many intersections of privilege and even Mei does not understand all of them. Martha, who is a Black woman, is extremely cautious (for good reason!) when Mei tries to make her son feel safe, because she does not feel comfortable making that promise to her children. In a sense, Mei does live in a reasonably sheltered and privileged environment that her dad has tried to build for her out of the privilege of white proximity by leveraging his white friendships, and the book is very much a book about both Mei and her dad beginning to understand that that is not sustainable.

Your book includes talk of death as a day-to-day event in the world of logging, but you also show the personal aspect of it by showing its impact. Can you talk about how you approached this sort of death for a young audience?

I was actually talked down to one death in the book from about twenty during the pitch process, although I don’t remember exactly which editor I spoke to about it (I think more than one was a bit dubious about me killing off half a logging camp). It was never really a question in my mind that young audiences could handle tragedy and death. Young readers today were born into a world of endless war, capitalism run rampant with no social safety net, and a level of unprecedented connectivity with the news cycle. They are very aware of what death is.

That said, it was extremely important to me to not inflict more trauma on marginalized groups. Even though the major incidence of violence happens to a Chinese man (Ah Sam), he is okay, and while he should never have been in that position in the first place, he isn’t actually harmed. The death in the book does not happen to a particularly sympathetic character, but it is nevertheless a death that affects other characters in the book deeply. Grief is complicated. It was really important to me to show Mei grappling with the death not because she is intensely affected by it, but because her best friend is. All deaths reverberate, through the people most in grief, to the networks supporting those people, and to people who have to navigate the grief and trauma in their extended circles.

There seems to be a lot of parallels between making food and telling stories, how both nourish and create community. Can you speak more to Mei’s ability to cook and tell stories and how that contrasts with her dad, who no longer tells stories?

I feel like I write about food and community and stories a fair amount, it’s definitely in Say It With Noodles, and in some of my “Curiosity Americana” comics. I think of food as a language, not specifically a love language, but just a language with a large range of emotions and tensions that can be associated with it.

Mei’s dad no longer tells stories, but that’s a reflection of how his immigrant life has been centered around work and building a better life for his daughter, while also trying to inure her to the violence and racism she will face outside the fairly comfortable borders of the insular logging camp. He is a realistic man - it’s not that he doesn’t believe in Auntie Po, it’s that he does not think that Auntie Po is a practical strategy for dealing with racial violence. He thinks that Auntie Po is a fantasy for children, and he is right, but he can’t bring himself to deny Mei whatever vestiges of a childhood she still wants to hold on to. But he expresses care through food, he expresses care by cooking for the Chinese workers every night, he expresses care by saving a piece of pie for Mr. Andersen, he expresses care by cooking all day so that Mei might have the opportunity for a better life.

You mentioned at the end of Auntie Po that your mother helped write the Chinese characters used in your dialogue. How did that work?

I don’t actually read or write Chinese, to my parents’ consternation but also their intention, since they did want me to be proficient in English and raised me with English as my (mostly) first language, even when I wasn’t living in America.

To translate the phrases I needed in the book, I would just write them in English, and then my mom and I read the pages together for context. Working closely together, we were able to decide on when we wanted idiomatic translations - some Cantonese phrases in the book are not literal translations of the English. For instance, there’s a place where the English translation for Ah Sam is “I’m fine,” but the actual Cantonese characters translate to something like “no holes, no tears.” After that, she would just write the phrases down in her own handwriting, and I would scan them and edit them into the book! If you look closely, you can tell the difference between characters she wrote and characters I wrote - hers are elegant, mine look like they are written by someone who never got past a year of Chinese school.

Can you talk about your tools and how they influence your work?

I’m not sure if you mean my woodworking tools or the drawing and painting ones! I think that my choice of watercolor as my primary medium really lends itself to my ability to establish a sense of time and place. It feels really correct for historical fiction, and I enjoy how it looks. This book was my first book where I used an iPad for digital pencils, and I’m not sure that was a significant influence, but it certainly made me much more efficient.

As for woodworking, I’ve been a carpenter for much longer than I’ve been a cartoonist, although at this point I have probably accomplished more as a cartoonist than as a carpenter. I build lots of things, which I think has sort of given me this more natural understanding of the way things fit together. It makes it a little bit easier to draw log cabins, of course, but I think it has also helped me a lot when I’m trying to figure out how a story or a panel layout fits together.

I don’t think that being a carpenter led me to being curious about the entire lumber manufacturing pipeline, but I do feel pretty at-home writing about the labor class and about forests and hard work, so it might be at least a little bit related. One of the things I love most is teaching kids that tools are just tools, and the capacity and ability to make things is absolutely something they can do. In the book, Beatrice and Mei are competent with simple tools (even if they obviously have adult supervision and help) and that was something I really wanted in the book.

I saw on Instagram that you’ve also been carving marionettes. What draws you to making puppets?

Well, right now I’m into puppets. I’m really into a lot of things, and I tend to get intensely obsessed over them for a period of time. Puppets have been a pretty consistent interest, but now I’ve been expanding into carving marionettes which is extremely hard, but a great challenge. I’m sure that I will eventually have a great answer when I’ve been carving marionettes for a bit, but right now, I just find them absolutely delightful.

What is your favorite kind of pie?

It changes frequently, but I am usually into berry fruit pies. Cherry, blueberry, strawberry and the like.

I like most pies with ice cream on the side, and I like apple pie with cheddar cheese on it.