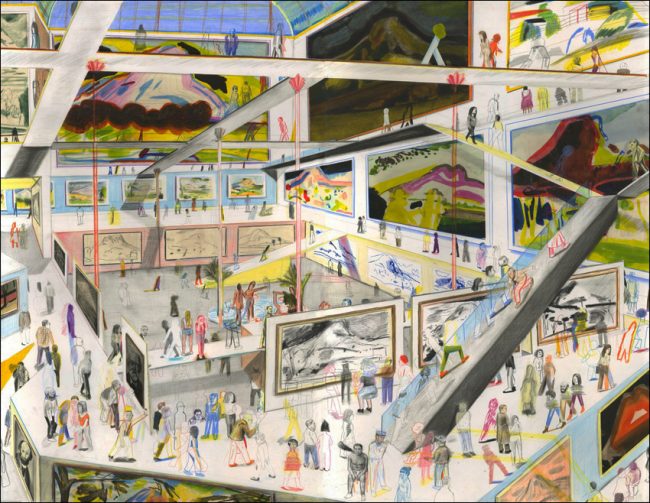

These days, thanks to numerous sales and galleries, comics get plenty of attention as art. Yet their status as oeuvres keeps on increasing. In France, a just-launched Actes Sud imprint called "Lontano" caters to this market with giant, unbound pages. Its debut offering is Yann Kebbi's Fondation Kebbi, a quirky museum-of-me done with dazzling craftsmanship. Fondation has twenty different "galleries" all of them showcasing Kebbi's prints, paintings, photographs and etchings.

Kebbi, 32, is a well-known illustrator. Work by him frequently appears in Le Monde, Libération, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the New Yorker. Since 2012, he's also published a book a year. Sometimes this will be a small-press affair like IMMO +, which was issued by 3 fois par jour. Other times, however, it's an elegant art tome such as the luscious, co-created Howdy.

In 2017, it was the one-of-a-kind comic La Structure est pourrie, camarade (The Structure Is Rotten, Comrade). Written by Viken Berberian, set in Paris and Armenia, this was an eccentric tale of family struggle and Soviet statues. The star of its story is a young architect who stumbles into a battle about civic heritage. It was Kebbi's art that held the narrative together, in pages so free that broadcaster Antoine Guillot called them "art that actually explodes, drawings propelled by a wrecking ball which, in the end, destroys even the narrative". None of this, he stressed, was problematic because everything about the book was so organic.

Author Berberian has lived in London, Paris, Marseille, New York, Los Angeles, Montreal and the Armenian capital of Yerevan. There, at the American University of Armenia, he is a professor teaching literature through comics. He and Kebbi worked on their book for years before they met. If that seems surprising, it's not strange for Kebbi. He is an artist whose projects often mirror his drawings in that they are intriguing yet unpredictable. In Fondation Kebbi, his art is sensational and it's made with everything from pencil sketches to prints and cut-outs.

There are twenty galleries in these fictive premises, but all of them hide the same basic structure. (Their action moves from left to right, flowing through layouts anchored by a set of squares. Not only does this make the varied rooms seem "real", it makes re-assembling the book's loose pages easier.)

Kebbi got the idea for his Fondation in 2018, during a residency in Aix-en-Provence. There, as part of the comics festival BD Aix, he was working in Paul Cézanne's old studio. Asked to re-imagine some of the master's favorite subjects, he zeroed in on Mont Sainte-Victoire. Cézanne was obsessed by the massive landmark, which he painted eighty-seven times. So Kebbi imagined a "Fondation Sainte-Victoire", a huge museum dedicated to all the artist's versions.

The work that resulted was a hit at the festival and also at the Paris art fair Drawing Now. Why not, thought Kebbi, use the same gambit to showcase his skills? This was the idea behind Fondation Kebbi, whose art is now on show at Paris' Galerie Martel.

The real charm of all these giant works lies in their mini-sagas, innumerable tiny stories shown by glimpses. They include that of a man and woman who meet, form a couple, become parents, then split. Few of their companions, however, have such a typical template. You're more likely to notice the ghost or the man on fire, one of the Fondation's nudists or its busy skeleton. Together, these visitors stare, sweat, smoke, snack, sunbathe, snap their selfies or even, sometimes, scream. Kebbi himself appears, as do both of his parents and several friends.

The tale also comes with its own superhero. Sporting a Superman cape and armed with a hammer he patrols the Fondation, shattering phones and iPads. (Around him, the institution's guards are all asleep. The single exception dies trying to chase a portrait, an artwork that flees its frame on penciled legs.)

I met up with Kebbi the morning after his signing. Unable to dedicate enough books the day before, he is back in the gallery to attack another stack. While we chat and sip espresso, he draws non-stop. That, he says, is what it's all about. "My anchor is always the drawing; ever since art school, it's been the basis of all my work. I think it's find helped me a range of sculptural and plastic solutions. But I try not to invest myself in a finished style; I'd rather explore different means of expression."

Kebbi has a lifelong relationship with the bande dessinée. " My first real love was Corto Maltese; Hugo Pratt was a big influence. I always wanted to make comics, that's why I studied art. But I also knew I had to do more than that." In secondary school, he chose an applied art baccalauréat. After that, at Paris' L'Ecole Estienne, Kebbi took a first diploma in illustration. He followed it with a second from the capital's Ecole nationale superieure des arts décoratifs.

He was working well before he graduated. During 2011, an art school exchange sent him off to New York and the Parsons School of Art. There, he spent six months "under really great professors, guys like Steven Guarnaccia, Ben Katchor and Jordin Isip." They showed his student work to American Illustration, who promptly published it in that year's annual. "Things just took off from there. That was the reason I started to sell stuff." Soon, he was represented by Michel Lagarde, the most powerful illustration agent in Paris. Lagarde also sponsored Kebbi's first book, Americanin. It features a French dachshund in love with Manhattan.

Much of Kebbi's rich art implies a sense of narrative. "Give yourself over to them," says critic François Landon, "and all of Yann's drawings tell you stories." But, outside his online offerings (some image-only), it was 2013 before Kebbi began a comic. Once he did, however, it was a monster; La Structure est pourrie, camarade clocks in at three hundred pages.

The huge project came out of an illustration job. "I was approached by two guys who ran this review, Dorade. They wanted me to illustrate one of Viken Berberian's stories, but it was a job for no money. I said, 'Okay, but in that case I'm gonna do it how I want.' When I sent off a few drawings, Viken wrote me back. He said, 'Hey, let's make this into a whole comic!' I said no, I'll just do the story. But when I sent him these really brutal drawings. I was struck by how – right away – he understood them."

Two or three years later, he says, they began La Structure. "Because we wanted to avoid the typical constraints, the usual codes of comics, there was lots of text. Mostly it arrived in dialogues, like a play. Which meant I had to treat it like a piece of theatre. The basic given was that these old buildings were getting razed to make way for 'the modern'. They were just seen as leftovers from communism. But my view of the whole thing is fantasy and I mostly drew it using Google. Viken sent me photos and I took some things from them, like the Soviet statues. But a lot of those I added weren't even from Yerevan – and some came from Russia. I totally re-appropriated and cheated. I didn't ever respect the story's site at all."

"What made our partnership work was the tone, the mood of Viken's writing was so in sync with how I draw. So nothing makes total sense and nothing is perfect. Making it, everything was a dialogue between us – we had a common understanding of the words, the way the storytelling should go. Viken's a great guy, he's a real enthusiast."

Kebbi's true bond with the tale lay outside its narrative. Because the story revolved around architecture, it implicitly posed issues of space. How do we conceive civic space and what does it "mean"? A sense of space, he says, is very basic to his work. "People always ask me, 'Where do you start? There's so much movement in your drawings, how do you ever compose them?' But, for me, what counts is the rapport with space. Whenever I begin, that's a determining factor. Once I get going, the drawing itself is almost spontaneous."

Each of the Fondation Kebbi pieces is a yard wide and almost two feet tall. "The most time-consuming thing about them was the drawing; every time, it took me at least four or five days. First, I would figure out the space and set the scene. Next I'd create the gallery's exhibition. Only then would I start to add the drawings. With this type of work – which is so exact and has a bunch of characters – what I like to add is lots of small, precise moments. So it's less a question of time than emotion. But that's how it all took shape, in layers."

"I like to tell stories," he says. "But I'm not good at writing so I prefer to draw them. Fondation Kebbi… it is a story. But I'm not sure how many people can actually read it. That's more the kind of thing kids are really good at. Deciphering a picture, contextualizing images, they're very talented at it. If you want to try something out, show it to a kid… because he'll usually see what you're trying to show. A lot of adults won't take the time or make the effort."

Where did his little Superman with the hammer come from? "The guy attacking all those digital devices? That's because I can't stand those things anymore! I was just in New York, at the Metropolitan, and a guy just shoved me out of the way to frame a shot. It takes time to look at art yet, now, barely people stand in front of something for seconds. Just long enough to take a picture, then they're gone. They can't even manage to use their actual eyes. I quite enjoyed giving someone else my feelings…someone who would take charge and get aggressive about it!"

Two things, says Kebbi, have consistently nourished him: the discipline of constant sketching and his interest in varied media. "My relation to image-making is fairly playful. I'm not obsessed with any one technique plus I like to have a lot of skills and resources."

One of those skills, however, is restraint. "The avalanche of images we have today can generate problems. Sometime, in my case, that makes it hard to really stay simple. Drawings in papers and magazines are often made to say something and the editors want their readers to get it right away. There's no time left over for complexity. For myself, if I have a message to convey in a drawing and it's too didactic, too visible, it's an error."

"After all, do drawings need to be totally legible? Can't they be a bit imperfect or emotional? I'm not sure we should push our drawing away from complexity. Where you try and impose a total legibility, it can steal your curiosity. Images are everywhere and yet – except in the most literal sense – no-one's really profiting much from that."

Kebbi has spent many years drawing sur le vif, on the spot. Last year, in Brittany, he exhibited several hundred sketchbook pages. Early on, he says, people were often more impressed by his sketchbooks than by his finished illustrations. ("It took me a little while to bridge the gap"). Much as he loves making prints, etchings and lithographs, for him they all lack the special thrill of drawing on paper.

The way he sketches, however, has evolved. "These days I think of it more as a job in itself and I'll dedicate a fixed stretch of time to it. I take a lot of periods off and, during any of those, I'll be sketching every day. But I don't do it all the time, I've stopped sketching quite so spontaneously."

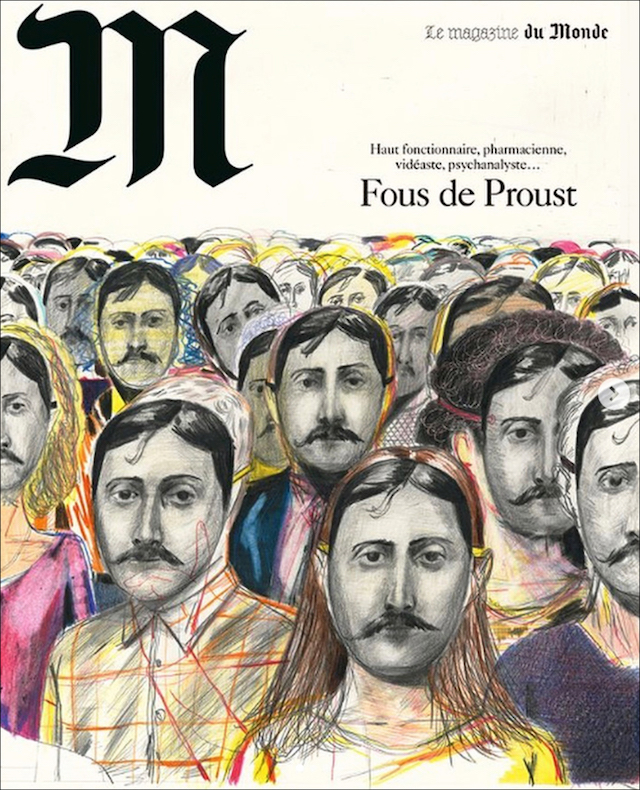

The week of his opening, Kebbi illustrated the cover story in Le Monde magazine. It was a profile of "Les Proustiens", the eccentric super-fans of author Marcel Proust. A fervent yet improbable lot, the Proustians made an engaging article. But Kebbi's clever art brought it a serious boost – and got it attention outside Proustian circles. Perhaps because, while it captured the cult's genuine ardour, his art also hinted at its sillier side.*

The Proustiens embodied what Kebbi's illustration does best. Rather than provide a visual echo of the subject, his art ads an extra level of eloquence. "With illustration, you always try to make the subject new. You need to avoid the usual schemes of representation, go for the unexpected. That's when you'll be the one an art director calls."

"Now, though," he laughs, "I have to read Proust."

Kebbi has long seen accidents as crucial. If he talks about mistakes, he uses verbs like "incorporate", "assume" or "absorb". "It's not that I'm 'better' if try to include them. It's that they provide a means of staying spontaneous; they're a way you can cultivate the unforeseen. Every artist evolves unconscious reflexes and it's always easy to start looking too finished. You have to work hard to keep your language fresh."

In 2014, Kebbi created a book called Choco et Gélatine. It was a simple, Romeo-and-Juliet tale for kids, about two candies separated by their ingredients. He drew it all using Photoshop. "I wanted to make drawings that would kind of defeat the medium. But, in our tiny world, the response I got was terrible. Nobody liked it; everyone asked why I did it. My response was always, 'Can't you understand the need to try something different?'." Ironically, he says, the book has sold more than any of his projects. ("So I guess the kids themselves were on my side").

He is not, however, seduced by pixels. "I see digital drawing as more of a technical challenge. Because the scale is always variable, it's not concrete – which means you have no real sense of the space. There are essentially no edges to your drawing. Plus, I find there's a side to it that's rather cold."

"Maybe I'm just more of a pessimist, " he adds, "but I think we give images way too much importance, we think too much about them. A drawing is a drawing is a drawing, you know…it's just a drawing. A good example is Charlie Hebdo. But…people now don't spend the time to really look. Take the opening I just had, for instance. Most of the people there didn't even realize Fondation Kebbi was a book. They assumed it was a catalogue, something that explained the art they saw on the walls."

He sets down his pencil. "I'm not even sure reading comic books is natural. Reading a text with images or, maybe even more so, reading a set of images as a sequence… It could be that's not so natural. Maybe that's why we have those codes, all those frames and bubbles. Just so everyone will be able to understand."

*In the spirit of full disclosure, I subscribe to the cult.

- Yann Kebbi, which includes illustration originals as well as the art from Fondation Kebbi, runs at Galerie Martel until November 2. Copies of Fondation Kebbi are available there. More books are due from Actes Sud's new Lontano imprint, including volumes by Gabriella Giandelli and Brecht Evens (in late October). You can see more of Yann Kebbi's work on his site or on Instagram.