“My purpose in philosophy is to design and present the image of an ideal man.” - Ayn Rand

It’s hard to overstate how much the year 1986 was a watershed moment for the medium of comic books. Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor's Tale showcased the artistic weight of the graphic novel when applied to serious topics like the Holocaust, DC concluded Crisis on Infinite Earths, striking a chord that they’ve been trying to replicate to this day; but the two most influential titles to hit shelves that year were arguably Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, written by Alan Moore and drawn by Dave Gibbons. Despite the vast differences between Alan Moore and Frank Miller, they are often lumped together in conversations because they combined the prestige of graphic novels like Maus with the mainstream attention afforded to comics published by DC. But one other similarity that both works have is that they are heavily influenced by the controversial philosophy of Objectivism.

Objectivism was invented by Russian-American writer and philosopher, Ayn Rand, who so named her philosophy because it was built on the premise that our objective reality can be perceived through our capacity for reason and logic. According to The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism and Rand herself, Objectivism is the philosophical belief that through reason, one can not only gain objective knowledge, but objective morality. [1] In practice, according to Rand, this meant that an individual’s pursuit of happiness was one’s only reasonable goal in life. Rand considered pity the ultimate insult to another individual, and selfishness an essential virtue rather than a flaw. She favored laissez-faire capitalism and believed forcing your personal ideals onto others (e.g. organized religion, communism, and socialism) was the root of all evil in society. [2] Ayn Rand’s two most important works are the philosophical fiction of Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, while The Romantic Manifesto is a collection of essays that deals directly with how her philosophy relates to the arts.

The philosophical principles of Ayn Rand and Objectivism at first seem to be in complete opposition to the ideals presented in most superhero comics. Heroism after all is an act of altruism for the collective good, two things Rand herself despised. Steve Ditko, the co-creator of Spider-Man and the most stringent follower of Objectivism in comics, focused on the idea of objective morality, with criminals getting what “objectively” deserved. This heroism was based on personal freedom, justice, punishment, and an unambiguous sense of good and evil. It never caught on in the same way Ditko’s mainstream work at Marvel did.

Unlike Ditko, Alan Moore attempted to discredit much of Rand’s teachings, while Miller embraced and modified them to his liking. Alan Moore sought to prove Steve Ditko’s Objectivist superheroes to be a paradox in his creation of the vigilante Rorschach. Frank Miller, like most modern libertarians (though he has disputed this appellation), seems to agree with aspects of Objectivism, and resolves the contradiction present in Ditko’s work by slowly transforming Batman’s motives in The Dark Knight Returns from a personal, militant drive to fight crime in Gotham, into a hero motivated to inspire others. Because they are both dealing with the themes of heroism, vigilantism, and morality, The Dark Knight Returns reads as an update to Ditko’s work as well as a rebuttal to some of the themes Rorschach’s character introduces in Watchmen, despite both series beginning in the same year. This is because both works come to completely different conclusions about the teachings of Ayn Rand.

Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbons’s creation of Rorschach wasn’t influenced by Objectivism so much as by Steve Ditko’s interpretation of Objectivism. Despite showing admiration towards Ditko for putting his political views in his art, Alan Moore admitted to finding Rand’s work “philosophically laughable.” [3] By applying a sense of realism to the heroism expressed by Mr. A. and The Question, Rorschach acts as a satire, parody and criticism of Ditko’s interpretation of Objectivist heroism whilst also paying homage to his legacy at Charlton Comics.

While Steve Ditko never had the same celebrity status that Frank Miller or Alan Moore have enjoyed, his legacy is just as strong within the comic book community. As the co-creator of Spider-Man, Ditko acted as the third pillar for Marvel’s rise to dominance in the 1960s. He is the first notable Objectivist in the comic book industry, and preferred to contribute to Charlton Comics and witzend after departing from Marvel, as they offered him the creative freedom he lacked in the ‘Big Two’ publications. When given this creative freedom, Ditko wrote overtly Objectivist characters like The Question and the more radical Mr. A., which were the direct inspirations for Moore's and Gibbons’ Rorschach.

There is more ambition to Watchmen than merely undermining a controversial political philosophy. With Rorschach, Moore and Gibbons are interested in tackling vigilantism and the crime-fighter trope that is present in Ditko’s Objectivist superheroes. Rorschach applies the radical ethos of Mr. A. in a more practical sense, and proves that having a strict code of ethics doesn't make someone ethical. According to Alan Moore, when Ditko was asked about Rorschach, he is quoted as saying “Oh yes, he’s like Mr. A., only insane.” [4] When Alan Moore tells this story, he pauses for the laughter that follows, the joke of course being that the only discernible difference between Mr. A. and Rorschach is how their creators perceive their characters' actions and worldview.

Because the concept of objective morality is essential to Objectivism, it makes such philosophy easy to associate with an extremist vigilante like Rorschach. In fact, the calling card of Mr. A. is literally black and white, symbolizing his mantra that 'there is good and there is evil and nothing in between'. Rorschach’s mask, as well as Rorschach tests themselves, are both clever ways to undermine the objective morality presented in Mr. A.'s stories. In Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons make it clear that Rorschach’s morality is not objective, consistent, or rational, but merely a code of subjective extremes. Rorschach is introduced in the story investigating the death of the Comedian, whom he considers a patriot, with his war crimes and attempts at rape to be “moral lapses”. By consistently showing Rorschach’s morality to be as subjective as the ever-changing mask he wears, Moore and Gibbons highlight the lack of credibility a vigilante like him has.

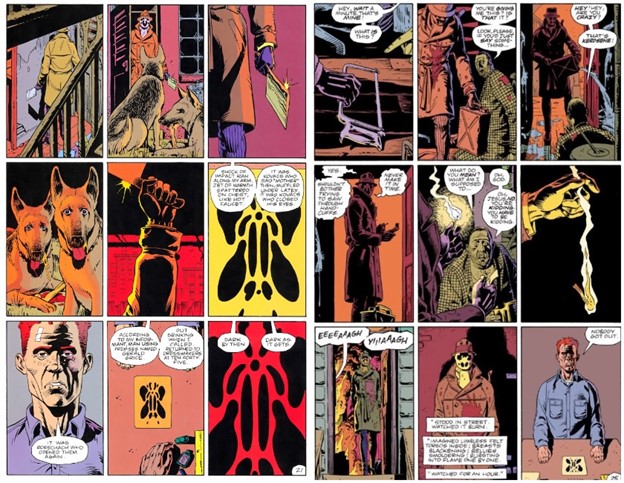

Issue six of Watchmen acts as both a homage to the first story of Mr. A., as well as a repudiation to his, and Rorschach’s, brand of vigilantism. Rorschach and Mr. A. both attempt to rescue someone who has been kidnapped, and both men deem the kidnapper to be an evil person who isn’t worth rescuing. The difference is how these stories unfold and the brutality of how they dispense justice. Mr. A. manages to rescue the young woman, convincing her to prioritize seeking medical attention over rescuing the kidnapper hanging over the ledge. Steve Ditko is clearly framing the story in a way that encourages the reader to view this decision as proof that selfishness is a virtue, like Rand says.

Alan Moore tinkers with this premise, to show it as the actions of an extremist. The first thing he and Gibbons do is make Rorschach come to the unpleasant conclusion that the little girl he was trying to rescue was killed, chopped up, and fed to the kidnapper’s dogs. This removes Rorschach’s actions from Rand’s tenets on selfishness, but ties them deeply to that of Mr. A., who views the world in good and evil, with nothing in between. We see how this outlook manifests a sadistic cruelty in Rorschach, as he brutally kills the dogs who ate the child with the hatchet used to chop her up. He then handcuffs the kidnapper to his radiator, gives him the hatchet he used on the little girl, and sets the house on fire after telling him he won’t have enough time to cut the handcuffs. What Moore is trying to do with Gibbons in this scene is show the danger of admiring a rigid individualist with a dehumanizing contempt for criminals and a dogmatic certainty of his convictions, when these characteristics are taken out of the context of a children’s comic. These characteristics can be seen in Mr. A. or The Question, but are qualities present in many mainstream superheroes.

One superhero who bears these character traits is Frank Miller’s Batman in The Dark Knight Returns. Frank Miller’s grim, gritty, and stylized take on Batman has even been accused of making Batman a borderline fascist. [5] Although calling Miller’s Batman fascistic isn’t inaccurate, it does the comic more justice to look at Miller’s work through an Objectivist lens. Miller often credits Rand’s The Romantic Manifesto for helping him define the nature of the literary hero, but doesn’t give Rand the degree of credit that Ditko did in his work. [6] This is why The Dark Knight Returns has a great deal in common with Rand’s philosophical fiction, but is not in strict adherence to the tenets of Objectivism.

Miller emulates Ayn Rand’s approach by presenting the external world as antagonistic forces against his “ideal man”. Miller doesn’t use Batman as a mouthpiece to espouse every opinion he personally has, like Rand often does, instead applying the relatively subtle (emphasis on the word “relatively”) approach of caricaturing many of the views he personally opposes. Miller casts a harsh light on the politicians, panel experts, and news anchors reacting to Batman’s return. It is through this demeaning technique that The Dark Knight Returns becomes more Objectivist than the Dark Knight himself, as Batman rarely engages with Miller’s targets of ridicule. Although Miller satirizes these institutions, he makes it very clear throughout that they are failing to do their job while Batman is succeeding in fulfilling theirs.

Because these targets of satire include a jingoistic warmongering Ronald Reagan on the conservative right, as well Carrie Kelley’s counterculture parents and the pretentious Arkham psychiatrist Bartholomew Wolper on the progressive left, the fringe right-wing perspective is harder to notice to those who are less familiar with Objectivist philosophy. Many modern conservatives that express fondness for Rand do not mention the fact that she thought very little of Reagan and despised organized religion and anti-abortion rhetoric as much as she despised socialism and social elites.

It becomes clear when one fully understands the unique right-wing ideology of Objectivism that The Dark Knight Returns not only undermines the contemporary views which Rand also opposed, but elevates Batman as a version of the ideal man Rand expressed in her Objectivist fiction. Although Frank Miller has never credited or discredited Rand’s philosophical fiction, Miller’s Batman has a lot in common with Howard Roark from The Fountainhead, who Rand considered to be her version of the ideal man. Both Bruce Wayne and Howard Roark are presented as controversial pioneers who are so exceptional that the powers which surround them attempt to quash their greatness out of a sense of fear and jealousy. While Roark is trying to design a building, Batman is trying to repair an entire city. Howard and Bruce both show an unwillingness to compromise and a pathological devotion to their missions, which is presented as a source of strength rather than a flaw. The main difference between the two is that Batman’s mission eventually becomes altruistic in a way Howard Roark’s doesn’t.

In each issue, Miller increases the degree in which the external forces are trying to undermine Batman’s mission, until he is finally forced to face Superman, who in many ways stands as the ideological opposite to Miller’s interpretation of Batman and Objectivism. This is because Superman’s biblical allusions and socialist origins were the very things Rand opposed in her writing from around the same time Superman was at the peak of his popularity. Superman’s origins bear many similarities to the Moses myth, and he has also been portrayed as a god-like figure over the years. On top of that, Superman was introduced as an idealist who championed many of the principles of FDR and the New Deal in his original Golden Age run. Combine this with the fact that he is shown in the graphic novel to be subservient to an unflattering depiction of Ronald Reagan, and Superman embodies everything Objectivists fight against. Miller frames Superman as an almost godlike figure who has been co-opted and weaponized by the American establishment to enforce their ideals onto Batman, who through sheer strength, intellect, and moral conviction can overcome even the godlike Superman.

Although Superman embodies everything Ayn Rand hated, by the end of the story Batman’s character arc has resolved with him becoming less beholden to Rand's philosophy than he was at the beginning. Unlike many of her characters, Rand seems motivated to change the perception of people around her through her work. In this way we can see how Miller is a libertarian influenced by The Romantic Manifesto rather than an Objectivist influenced by The Fountainhead or Atlas Shrugged. In fact, Miller resolves the contradiction of the Objectivist superhero by having Batman’s character arc transition from a figure similar to Objectivist characters like Roark, into someone who sees the value in the example he is setting for others. This sense of strong leadership is what makes it feel less hypocritical than that of Mr. A., but is also what courts accusations of fascism.

Miller’s Batman is trying to rebuild Gotham City, whose decline can be blamed on government intervention against the innovative work of superheroes, and the corrupt or misguided nature of these various government institutions. Through Batman’s success, he starts being looked at as a viable alternative to these institutions. One reason there aren’t many Objectivist superheroes is that Objectivism pairs uncomfortably with the notions of great man theory that so often permeate the superhero genre. By inspiring others through his rugged individualism, Batman has converted the citizens and police of Gotham City, amassed a private army, and is in open defiance against the U.S. Government. By the time Batman has cultivated such a following, his fight for individual freedom makes his Objectivist values ideologically indistinguishable from an aspiring authoritarian.

The desire to inspire others is a quality lacking in Rand’s idealized characters, yet it is a quality Rand herself had. The very idea of trying to convey an “ideal man” implies a desire to set an example for others, yet Roark very pointedly doesn’t seem to care what others think. This distinction gives credence to the idea that Miller took inspiration from The Romantic Manifesto and not her two most popular books. This is also the most compelling argument Miller has against Moore in his Randian reinterpretation of Batman. For all the morally questionable things Batman does in The Dark Knight Returns, Miller makes a point to show his presence is inspiring others to stand up for what they believe in.

The capacity to inspire others is one of the main reasons for the superhero genre’s popularity; even Rorschach is admired for his convictions in certain comic book circles, much to Alan Moore’s dismay:

“I meant him to be a bad example, but I have people come up to me in the street saying, ‘I am Rorschach! That is my story!’ And I’ll be thinking, ‘Yeah, great, can you just keep away from me and never come anywhere near me again for as long as I live?’” [7]

It is fair to say that no superhero in Watchmen is supposed to be ideal; in fact, they are quite the opposite. Rorschach is a corruption of a familiar archetype that encourages the reader to question things we may take for granted in the superhero genre. One could say Watchmen’s purpose is ideologically opposed to Rand, attempting to destroy the image of an ideal man.

The philosophical, political, cultural impact of Ayn Rand and Objectivism are far-reaching and indirect, especially when you consider that very few people call themselves Objectivists, favoring the terms neoliberal and libertarian instead. Putting aside the political impact of Rand’s work, she has also inspired many individuals in various artistic circles. Neil Peart, the drummer and main lyricist of Rush, credits Ayn Rand in the inception of 2112. Both Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead have been adapted multiple times into film, television, and plays. Yet Rand’s individualist streak seems to have rubbed off on her followers, who often credit her as an influence but can rarely call themselves Objectivists in the purest sense of the word.

As I mentioned before, it is somewhat ironic that Objectivism is built on the premise that through our capacity for reason and logic one can perceive an “objective reality”. The irony is that many of the tenets expressed through Rand’s philosophy are expressed through the rhetorical frame of fiction, in order to present protagonists and antagonists as ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys’, rather than a more conventional essay style which would lean more on reason and logic. Even more ironic is that this very rhetorical frame is used in Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns to distort her philosophy through their subjective interpretation of it.

Neither Frank Miller nor Alan Moore fully subscribe to Rand’s work, and seem to disagree with one another on its merits and faults. Yet it can’t be denied that in Rand’s attempt to discover an objective reality and an objective morality, she inspired two of the most influential comic creators of all time to unintentionally prove her wrong.

* * *

[1] The Mike Wallace Interview of Ayn Rand 1959

[2] The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism pg 363-4, Ed. Ronald Hamowy

[3] https://www.polygon.com/comics/2019/10/24/20925070/watchmen-rorschach-inspiration-alan-moore-batman-the-question-mr-a

[4] Ibid

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2016/apr/01/frank-miller-fascist-dark-knight-modern-archetype-donald-trump

[6] Sciabarra, Chris Matthew. "The Illustrated Rand." The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 6, no. 1 (2004): 1-20. Accessed September 25, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41560268.

[7] https://www.stevensurman.com/rorschach-from-alan-moores-watchmen-does-he-set-a-bad-example/

* * *

FURTHER REFERENCE

A Place for Bold: Understanding Frank Miller

After His Public Downfall, Sin City's Frank Miller Is Back (And Not Sorry)

Sciabarra, Chris Matthew. "The Illustrated Rand." The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 6, no. 1 (2004): 1-20. Accessed October 10, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41560268.

Forward of Witzend #3, written by Steve Ditko

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, Ronald Hamowy, SAGE Publications

Alan Moore created Rorschach to dunk on Randian superheroes

Alan Moore's Watchmen And Rorschach: Does The Character Set A Bad Example?

Frank Miller gave us the best Batman — and the worst

Are Frank Miller's politics visible in his comics?

Frank Miller's fascist Dark Knight is a very modern archetype

When Were Superheroes Grim and Gritty?

The Single Most Important Year in Superhero History Was 1986