Previously: Part One, Part Two

VII

So far we’ve told a pretty straightforward story about a character in a time of change. Denny O’Neil was in charge of almost a decades’ long initiative to update and modernize Batman, bringing the character closer to popular contemporaneous iterations. If you didn’t know the rest of the story you might think O’Neil’s vision of the character became permanently ascendant. To a large part, it has, or at least - it did. For a while. But there were some bumps along the way.

Enter Joel Schumacher.

Schumacher is an interesting character in Batman history. He undoubtedly had an impact on the character. Many consider it a negative impact. The Christopher Nolan Batman movies, universally beloved as they have become, launched under a cloud. Remember that? Batman Begins almost seems a modest production in hindsight because they weren’t sure if people were ready for another Batman movie just eight years after a particularly controversial entry. It goes without saying that most people generally seemed to prefer Nolan’s version of the character.

You probably see where this going. Don’t flinch. Don’t be squeamish. Don’t lie to yourself. Deep down you all knew what we were here to do. Yes, the time has come to defend Joel Schumacher.

Now, first of all, it should be said that as controversial as his tenure in the director’s chair proved, his first instincts were sound by any measure - said instincts being more or less a straight adaption of Year One. Schumacher was a very good director with strong commercial instincts that enabled him to deliver memorable work in a number of genres. The guy who did The Lost Boys, Flatliners, and Falling Down could have sunk his teeth into a darker and less cartoonish iteration of the character, no question.

As we all know this is not what Warner Brothers wanted in 1995. They needed to split the difference from Tim Burton, who had given them one very commercial Batman movie in 1989 and another slightly less user-friendly Batman movie in 1992. People stood in picket lines outside McDonalds because Michelle Pfeiffer was just too damn sexy, a funny bit of trivia that is 100% true. Perhaps not a thousand ships, but as close as we will see in this fallen world. The problem was, Batman Returns still wasn’t a flop. It didn’t come close to the performance or impact of its predecessor, but as mentioned that was something more resembling a generational phenomenon, and they weren’t likely to hit that level of intensity again, at least not for another generation. But it still sold a lot of toys, even swimming against a tide of controversy and diminished returns.

That’s what Warner Brothers wanted. The idea of going darker and less toyetic found little traction. They needed toys and Happy Meals and a lighter tone. Now, Schumacher was above all a seasoned professional. It could not have escaped his notice that the Batman he was commissioned to make was at odds with the Batman most Batman fans seemed to dig, possibly even at odds with the version he seemed to dig. But he had long since mastered the most vital art for any commercial artist - that is, the ability to take any job and make it both watchable and stylish, more or less to order. So he gave Warners precisely what they said they wanted and the result was the brash, colorful, eternally toyetic mess that is Batman Forever.

Which promptly surprised everyone by outperforming modest expectations. It’s an odd movie and I struggle to describe it as “good” - cacophonous in the way of a great deal of 90s art, filled with a lot of contrasting tones placed haphazardly one on top of another. The art direction is certainly memorable if not quite as focused as it would subsequently become. The best part by far was the soundtrack album - Method Man does a track about the Riddler, definitely worth your time. I believe some dude named Seal had a bit of a minor hit somewhere along the way. It certainly profited from the dumb luck of having signed Jim Carrey to play the Riddler at the last conceivable moment he could still be considered a rising star, around the time of the first Ace Ventura film but before he went supernova with the one-two punch of 1994’s The Mask and Dumb & Dumber. By the time Batman Forever premiered in 1995 Carrey was the film’s biggest star and audiences bought tickets accordingly.

The performers seem to be on different pages regarding what kind of movie they’re making, and it wasn’t by accounts a particularly fun movie to make. Tommy Lee Jones apparently hated Jim Carrey and Val Kilmer hated everybody. But it was popular. It was specifically designed to be ingratiating. Schumacher was a very clean director with a taut sense of pacing, and his movies don’t have a lot of fat on the bone. It doesn’t make a lick of sense but it hits all the beats. I saw it in a packed theater the Saturday after it premiered and people cheered. “Holy rusted grate, Batman!” killed. The 90s, man.

Now, imagine for a moment what it must have been to be Joel Schumacher. He made a garish toy commercial that just happened to be effective crowd pleasing summer entertainment. The most popular element of the movie was the love theme - the best cut of the movie is the “Kissed by a Rose” video, for crying out loud. It’s difficult to imagine he went into making Forever with any idea that he’d be making a sequel to such a patchwork cashgrab, and especially difficult to imagine he ever thought he’d be given more or less carte blanche to continue in an even more colorful and outlandish direction.

Perhaps worth mentioning here Schumacher was gay, something about which he was quite outspoken. He had lived through AIDS. He knew and cared enough about the queer history of Hollywood to buy Rudolph Valentino’s horse farm from Doris Duke. To my reckoning it would be very difficult to argue Schumacher would have been unaware, on any level, of what he was doing when he made Batman & Robin. He knew camp. He knew arch. He knew gay history, both comic and tragic. He certainly understood queer subtext.

Imagine him, then, driving to work at the studio every morning, shaking his head over and over again, talking himself through the day’s filming, incredulous in full knowledge of the fact that he was making one of, if not the gayest big budget action film that has ever been made. That they asked him to make. I can’t think of any gayer, honestly - take it from me, a noted gay. Did he worry he was going to get caught? The domestic scenes play like a Joan Crawford weeper, the action sequences are lit like an Andy Warhol happening. The camera regards both men and women with respect while still managing to communicate the plain dewy-eyed fact that George Clooney, Uma Thurman, and Alicia Silverstone are among the most beautiful people in the world. Arnold looks like he’s having a blast camping it up - just when does Arnold look like he’s having fun? I am also given to understand that Chris O’Donnell is in the film.

I’m conflating and compressing a lot, of course, given that it takes a lot more than one man to make a movie. Especially a movie as complicated as a Batman movie. Kind of like a comic book editor, you don’t actually see the director’s hand onscreen even if you also know they have approved every element thereon, or at least were involved in the wrangling thereof. Apparently it also wasn’t a particularly pleasant movie to make for the actors involved, partially because Schumacher’s direction leaned heavily on the idea that they were acting in a cartoon. He needed the kind of studied flatness Adam West and Burt Ward had mastered from his actors, apparently not a wavelength on which every actor can vibe. Barbara Ling’s colorful production design took Dick Sprang to his logical conclusion and I can see why an actor would feel lost. Everything had to be big. Ling won an Oscar recently, for Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, so you can’t say Schumacher didn’t have an eye for talent. Her work for these films is revelatory.

Warner Brothers should have known better since they made the same mistake twice. They gave Burton carte blanche to follow up an extraordinarily successful movie and were surprised he came up with something far more distressing and personal than they expected. Well, I’d argue Schumacher gave them something far more personal than they bargained for with Batman & Robin, too. It just didn’t occur to them that Schumacher would present the same problem from the opposite direction. Instead of melancholy introspection Schumacher gave them brilliant color and fantastic motion, a loud, occasionally abrasive and doggedly strange movie that could not have been made by any other director at any point in history other than by the guy who just happened to be in the director’s chair of the biggest superhero franchise in the world when the studio said, “give us color.”

Well, he must have thought, if you insist.

Please, do not take my word for it: just watch it. Turn the volume off if you need. Look at the color. Lean into the baroque excess. Enjoy the scenery being chewed like the crew refused to feed the actors and hid sandwiches in the wall. The cinematography! Every inch of every frame has been composed almost to obsequiousness. It is, frankly, a marvel - it anticipates every excess of the digital color era. Look at Batman & Robin and then look at the Wachowskis’ Speed Racer, or Nicolas Winding Refn’s neon palette, or anything by Taika Waititi or Panos Cosmatos - anyone who has made hay from unleashing garish color onto the drab gray blues of the twenty-first century. Joel Schumacher was twenty-five years ahead of his time. It was way too queer for 1997 but makes so much more sense today.

Quick cut to New York, the offices of DC Comics, early 1997. Denny O’Neil is working late, sitting alone at his desk, poring over promo materials and press clippings for Batman & Robin under the wan light of a single desk lamp. He is loudly chewing handfuls of aspirin.

OK, I made that up. I’m sure he had more of a sense of humor about these things. He had to have. It’s not like they were ever going to stop selling the Underoos and Happy Meals, not like the 60s show was ever going anywhere. While I doubt O’Neil lost any sleep over the Batman ‘66 publishing rights being tied up in limbo for the entirety of his tenure as editor, it’s not like the show itself ever left syndication. The fact that the publishing division found it more profitable to skew older was merely one element of the marketing for a character whose significance far outstripped the publishing division. If anything, the darker Batman who became more and more prominent in the books through the 90s was out of step with the rest of the company’s desire to see Batman continue as a kids’ aisle staple.

So, here’s the slightly weird part: Denny O’Neil died on 11 June 2020, from a heart attack. Just eleven days later Joel Schumacher died of cancer. What’s more, they were born in the same year, 1939, just a few months apart. For a few years in the mid 90s these two men almost exactly the same age worked on Batman, simultaneously if never together, and their views of what Batman was and could be were the two most dominant voices in that conversation in the years leading up to the turn of the millennium. O’Neil devoted much of his life to the Caped Crusader, thought deeply about how the character should look and act, how readers wanted him to look and act. Schumacher was, from the perspective of the studio, just another director who got the job because he could be counted on to wring as much value as possible out of a property that wasn’t at the moment commanding a lot of respect.

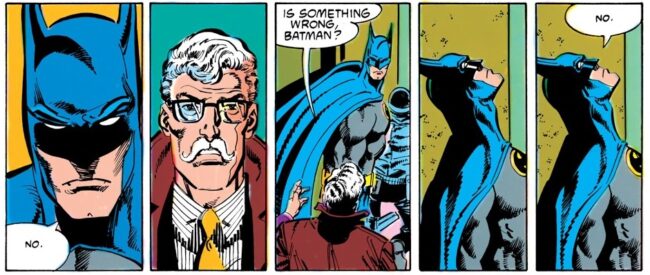

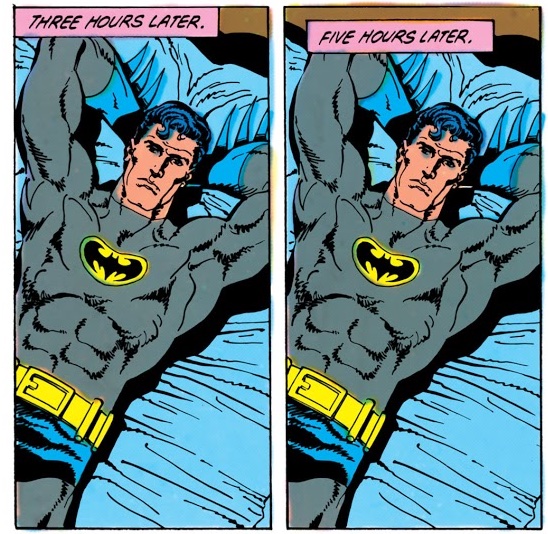

O’Neil’s vision was by far the more popular. When Nolan recreated the character with Christian Bale, much of what made it to the screen came directly from O’Neil’s version. Now, I don’t particularly care for those films myself. I never rewatch them. There’s not an ounce of whimsy in Nolan’s Batman. The very idea of whimsy seems absurd in that milieu. I submit something that O’Neil understood well - no matter how dark or gritty the setting, Batman still always has to have a flair for the theatrical. Batman is a performance, after all. He may ostensibly be as straight-laced as it gets, but just the act of putting on a costume displays the ineradicable flamboyance native to all super heroes. Ignoring it completely is just silly. O’Neil gave us “back to basics,” after all, but don’t forget he also gave us shirtless Byronic Batman dueling R’as al Ghul under the desert moon. There needs to be just a pinch of swashbuckler or the recipe turns bitter. Batman can laugh in the face of death sometimes, as a treat.

Now, look at the two poles we’ve established here, two seemingly opposite and diametrically opposed interpretations of the same character. Between those two kinds of stories you find the entire spectrum of possible Batman stories - grim formalist neo-noir crime thrillers to sensual feasts of pure color and design. This spectrum also seems to index neatly to another, larger discourse, regarding masculinity. Is it as simple as that? Huh, maybe it is.

Another never mentioned aspect of the Schumacher films is that, even after you sweep away how the movies look, the stories themselves do things Batman stories almost never do. Batman Forever sees Bruce Wayne entering therapy and dealing with his childhood trauma. He ends the movie with a girlfriend (also his very unethical therapist, played by Nicole Kidman at the absolute height of her adorability), and a child (in the form of Chris O’Donnell’s Large Adult Son Robin). This strangest and loudest of the Batman films ends with Batman having created a new nuclear family to replace the one he lost.

The Bruce Wayne plotline for Batman & Robin goes even further. Alfred gets sick. Bruce has to confront the fact that Alfred was his real parent in every way that matters. It’s hardly a novel beat, but it is a novel approach for a Batman movie. Bruce even says “I love you.” Has he done that in the comics? He has to have done so at some point, right? It’s a simple thing, people say it every day in every situation - even fathers and sons are given to express such things, on special occasions. But it’s amazing to see such naked emotionality in a Batman movie.

Perhaps that’s why they could never forgive him. It wasn’t just the gloriously queer mise en scène that stands out. Schumacher’s Batman is fundamentally a different kind of man, a grown-up who moved past the limitations of revenge as a singular motivation and into a more holistic understanding of justice. This Batman had it both ways, too - he got to be emotionally available and got to look fabulous while doing it. Is that scary? Is emotional availability “queer coded” now.

For all the shit he got, Joel Schumacher had ice water in his veins. He took an unlikely blank check from Warner Brothers and in turn produced one of the most gleefully, joyously strange movies that has ever existed, a pre-millennial paean to a half-century of queer and underground aesthetic wrapped up in the neon gauze of a toyetic Batman movie. He dredged up just about every element of the character that had been deliberately and painstakingly buried and repressed, from the colorful tone and sound effects to the queer subtext and hokey plot devices - all years before Morrison’s Batman fell down in a pile of garbage and got up screaming about Zur-En-Arrh. And even though it has endured decades of mockery the film still wasn’t a financial disaster, purportedly making its money back with foreign receipts.

One must imagine the damn fool grinning.

VIII

This raises the specter of another Batman, the most forbidden Batman of them all - more forbidden than Adam West, or Morrison’s Black Casebook, even more forlorn than Joel Schumacher’s well-balanced merry men. In a word, I mean the Batman of Earth 2. Yea verily, I speak unto you even of the Paul Levitz - nay, the Roy Thomas Batman. That guy started off grim and dark, just like our modern specimen, but mellowed in the company of family and friends. With that framing the character’s oft-derided outlandish 1950s appear an expression of comfortable maturity. His story was told in its entirety, from Detective Comics #27 in 1939 to his death in 1979, and even the reading of his will (which almost destroyed the JSA). His life didn’t make sense as a career until later on, after the multiple Earths gimmick had been established and creators realized they could, you know, do interesting things with the older Batman of Earth 2 that they couldn’t with the younger guy stuck on Earth 1. Earth 2 got to marry Catwoman. He got an ending. Earth 2 Robin got to grow up and wear the ugliest superhero costume in history, and yes that’s a hill to die on.

My favorite Batman story? The Brave & the Bold #197, The Autobiography of Bruce Wayne!” I found it in the first edition of The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told, still an invaluable historical resource. Written by Alan Brennert with art by Joe Staton and George Freeman, “The Autobiography” is a romance of sorts. It’s the story of how the Earth 2 Batman first revealed his identity to Catwoman - Scarecrow is doing something in the background but it’s not important. Oh yeah, it’s also told in flashback by Batman at the end of his life, reminiscing about his late wife not long before his own passing. Guaranteed three-hanky affair, I promise.

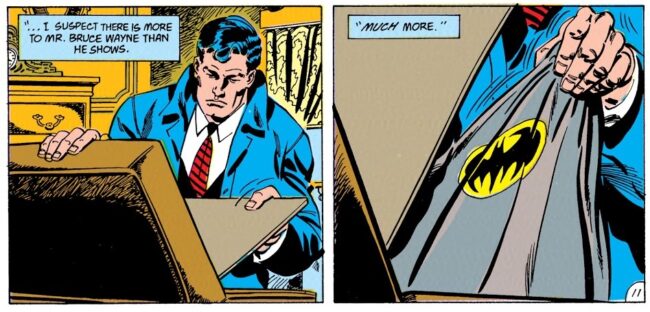

That story was published in 83 and serves as an appropriate lead-in to the Thomases’ most significant Batman story, 85’s America vs. The Justice Society. (I refer to Thomases plural as Roy was sharing the writing duties with his wife Dann for most of his output during this period.) It’s an odd Batman story in that the character isn’t actually in the story, but I nevertheless invite you to read it through that lens because the story is still largely about him. It takes place after Batman’s death and after the public release of his diary has leveled charges of treason against his surviving comrades in the Justice Society of America. Much of the story is Batman’s surviving family, friends, and coworkers coming to grips with the kind of person he was. Why would he lie about the JSA working for the Axis? Was he even lying? How much did they even know someone who was so paranoid he could keep secrets like that from his closest friends?

This was the Earth 2 Batman, mind you, the Eisenhower-era “Time Crimes on Venus” guy. Even that anodyne fellow was still too paranoid for the likes of Alan Scott and Jay Garrick - I mean, come on. Jay Garrick? No one distrusts Jay Garrick. So what do his intimates finally conclude about the old man? Well, he was a good and capable man with a reactionary streak that could have led him down the path to paranoid crank, but was mostly kept on the straight and narrow by the love and respect of the people with whom he surrounded himself. The diary libel is eventually straightened out through a rather complicated series of events that don’t bear repeating, but it’s a Roy Thomas experience so you should probably prepare yourself for recaps of other comics used in lieu of dramatic climax. Per Degaton is involved, sadly. Leave it be said you should at least check the series out for strong work from stalwart vets Rafael Kayanan, Rich Buckler, and Jerry Ordway.

In the later Earth 2 stories Batman is just another member of a very large cast, retired and mostly consigned to the background until killed in Adventure Comics #462. It’s interesting to see the character primarily through the perspective of others, without so much of the ever present metatextual awareness that Batman is and should be at the center of his universe. His faults and foibles stand out when the plot isn’t working overtime to create justifications. It's easier from this perspective to see him as a man who made mistakes and often as not triumphed in the overcoming. Odd that a version of Batman so directly tied to his most juvenile era would seem so well rounded in hindsight.

These were my thoughts as I pondered that splash to Batman #496, with the barrel-chested Batman stumbling away from carnage. Jim Aparo was born in 1932, he would have grown up watching the the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films - I think you can still discern that idealized physique, or something very much like it, in Aparo’s character. A mid-century picture of the strongman. What sticks out to me is the vulnerability, gone now in an era where the character never leaves home without body armor.

Tim Burton’s plastic musculature looks practically quaint now, chiseled abs almost within the realm of human proportions. The fake muscles split from that moment into two streams. One of those streams led further down the path of exaggerated sensuality, the mannerism and enthusiastic physicality, even eroticism in Batman & Robin; the other to Christopher Nolan and the manufactured military precision with which his Batman armors himself. All mass and dimension, lacking so much as an intimation of shape or sensuality. No risk. No danger only violence. These were my thoughts as I reread Knightfall last year, 2020, during a long summer marked by accelerating police violence at nationwide protests against accelerating police violence. The police all wear body armor now, just like Batman. They wear masks, too. “Where does he get those wonderful toys?” Pentagon surplus.

The intersection of justice and masculinity is where Batman resides, where his fans and his creators like him. It’s contested space. It’s not cultural space to be ceded, not without consequences. These are our stories, too, and yours. Which is how I make peace with the fact that there are many Batman stories I do not like, many Batmen I find abhorrent. I dislike Bale’s Batman. He seems a charmless thug with an authoritarian personality, but he’s still very much Batman. Just as George Clooney’s suave and mature family man is also very much Batman. They don’t annihilate one another, they linger like photo negatives placed in a stack. Existing in compulsory dialogue.

Batman fans do understand this. Although as I mentioned I think of myself as more of a Superman person, I acknowledge that Superman fandom is probably a more uptight place. Arguments about Superman among Superman fans are as likely as anything just to turn into arguments about whose dad is better. It bothers us when Superman acts off-model, and I think the reason is pretty simple: many Superman fans identify the character very closely with their own internal moral compass. Seeing Superman say or do something I don’t agree with feels wrong in a way that seems vaguely embarrassing to admit. Superman fans in my experience like the Superman of 2021 being substantively the same dude - or at least being recognizably linked to - not just the Superman they grew up with but every Superman since 1938. That impulse seems to cut across Superman fans young and old, tho’ I’m sure the ones who disagree will tell me so.

Batman fans, I think, have a much healthier understanding of the fact that there isn’t just one Batman. Is there a Batman fan who loves every Batman? Every Batman? Denny O’Neil tried to institute something resembling a standardized version of the character during his tenure as editor, and while he succeeded in establishing a framework for subsequent decades it was never going to be the only version. I can’t realistically complain too much about the Nolan Batfilms - outside their sheer ubiquity - because they coincided precisely with the release of the upbeat Batman: The Brave & The Bold cartoon, possibly my favorite Batman of the new millennium. As dissimilar from the films as possible. Batman can survive multiple versions on the market.

I think the more brutal and vengeance-driven Batmen are less effective because their means constantly undercut their stated goals and intentions. But I suppose any side of the argument could claim the same, or it wouldn’t be an argument. Still and all those kinds of stories don’t make as much sense to me, in the same way that most police shows have never made a lot of sense. If a story purports to reflect the criminal justice system (or the military, or history, or a biography, etc.) but reflects only an advantageous distortion, I can’t look past the agenda the distortion reflects. The distortion obscures the stakes in our own lives by obscuring true incentives for real behavior. For better or for worse that’s how my mom raised me, she worked with the police and knew from experience the shows bore little resemblance to reality. She was wary of law enforcement and disliked cop shows because of it.

That’s one reason I like my Batman stories with a little more fantasy sifted in. Batman doesn’t have to be a cop. There are lots of ways to help people that don’t involve relentless reification of the carceral state. He’s got lots of fun villains who aren’t purportedly mentally ill or caricatures of inner city gangbangers, lots of pals who aren’t cops. Why, sometimes they even let him fight time crimes on Venus.

IX

A while back I stumbled across one of those endless rounds of online Discourse on the question of whether or not Batman was a fascist. A weighty inquiry in an age of near-constant state repression, to be sure, but one I’ve been over a few hundred times already and I’m not even that old. My answer is, yes, of course. There are many turgid reactionary Batmen and many colorful compassionate Batmen, and all of them are equally Batman. The glory is that he can be both. He can have it all ways, because he ultimately means so much to so many people he means almost nothing solid at all. Lest we forget, he’s not real.

The idea of a man who puts on a mask to step outside the law can tend in any direction. I’ve long maintained it foolish to pretend violent power fantasies are solely the province of conservatives. There are lots of different crimes, after all, lots of different causes of crime and ways to effect justice from those causes. There is no shortage of injustices considered too small or inconvenient for the people putatively tasked with solving these problems to bother. Or not even illegal at all. As long as that situation continues the desire for stories about Batman, or others who scratch that itch, will never wane.

I taught English for a few years but only used comics as texts twice. The first I used was All-Star Superman, in a class devoted to fantasy literature. The second was Watchmen, in a class whose syllabus was entitled, ahem, “Let’s Read Watchmen.” It was a fun class to teach. My thesis regarding Watchmen, which I spent ten weeks teasing out with my students, was that Watchmen could be understood as a collision of two texts: the Oresteia of Aeschylus and Woodward & Bernstein’s All the President’s Men, placed together in the context of the Cold War. Watchmen begins with a burglary investigation, an event to announce that the primal American myth has been supplanted by the trauma of recent scandal. Moore’s plot is twisted into the same shape as the Washington Post’s investigation: a bad burglary catches the attention of just the pair of eyes needed to follow a very thin thread into a labyrinth of corruption at the center of which waits the most powerful person in the world. This plot returns like an echo in our entertainment for years after the resignation.

The question lingers, however, right where Woodward & Bernstein’s factual account of pervasive injustice leaves off: how are we to live in the presence of such pervasive injustice? Here is where Aeschylus enters the scene. The Oresteia is concerned with litigating the liminal region between revenge and justice. An unjust act creates a spiral of retaliatory violence that threatens to swallow society whole. It requires the intercession of the gods to put a cap on the slaughter by convening the first courtroom to arbitrate the matter. Not all are satisfied by the judgment but accept that dissatisfaction as a necessary consequence of living in a stable society, one no longer governed by the pique of hot blood. Moore sees just how integral the idea of the vigilante is to American culture, how it taps into our most ancient fears about nationalism and race, understands just how self-defeating these myths are. Not hard to see how corrosive and seductive the idea of the righteous vigilante continues to be, how the very idea of taking the law into your hands to preserve justice can lead inevitably to atrocity and the summary unraveling of the social contract.

I’ve made a few derogatory statements about Nolan’s Batman films, but I should say that for all my problems they do eventually reach this wall. It takes three movies but Bale’s Caped Crusader with the Cookie Monster voice does eventually get to the end of that cycle, the point where he has to look outside himself to see that revenge untempered by restraint motivated by a desire to control simply begets eternal metastasizing violence. The only thing waiting at the bottom floor of that hellish escalator is chaos. He steps away from being Batman and the movies end on that note (notwithstanding the kid from Third Rock from the Sun finding Bruce’s giant box of pornography), with the last image of a smiling Bruce Wayne enjoying an actual retirement with his family. Batman almost never gets to ride into the sunset, and I appreciated the break from the mold.

Of course, that doesn’t take away from the generally dreary tone, bloated scripts, inert art direction, and the hard fact that Christian Bale’s Batman is objectively bad at being a superhero. He makes every situation worse. Go back to The Dark Knight, tell me the situation isn’t exacerbated at every turn by the Caped Crusader’s incompetence. Ah, well. They somehow made Anne Hathaway the least sexy Catwoman of all time, what more proof do you need that those films have problems?

Now, Joel Schumacher, he knew how a woman’s face should be lit. And for all the discussion about whether and how the Dark Knight might best please a woman, it must be noted that Schumacher’s Batman has a genuine love theme. Do you know what Batman’s love theme is? Of course you do, it’s “Kiss From a Rose” by motherfucking Seal. I mean, come on: “now that your rose is in bloom / A light hits the gloom on the grey”?

It’s 2021. Let us be perfectly frank: Joel Schumacher was so far ahead of his time that not only did he give Batman a love theme, he gave Batman a love theme specifically about going down on a lady. Twenty six years ago, in an immensely successful movie, with an instant classic song. And before you ask, yes, he did pick it, not some studio flack: Schumacher personally found and fought for the song’s inclusion in the film, this after “Kiss From a Rose” had already been released months previous and disappeared without a trace. The rest, including Seal’s entire career, is history, thanks to Joel Schumacher, who shall now and forever be remembered as Batman’s greatest wingman. (And probably Seal’s, too.)

From this vantage perhaps we can see more clearly, then, the precise point of departure between the Schumacher and Nolan Batman movies. Nolan takes Batman to a place where he recognizes revenge cannot beget justice and his journey stops there. Schumacher however begins with the assumption that the desire for revenge is an unhealthy trauma reaction, something to be moved past. That driving desire can however be used to form the basis of something new beyond that paradigm, something healthier and more sustainable. Growing up, how utterly banal! Too bad people rejected Schumacher’s Batman so hard that the overcorrection eight years later was two hours of shirtless Christian Bale hitting things and grunting.

When I said earlier that Knightfall had become more significant in hindsight, I didn’t mean because it was a slight inspiration for the third of Nolan’s Batman movies, The Dark Knight Rises. That was certainly important, inasmuch as those movies were very successful. But more than successful they became idiomatic across the culture. Everyone knows them. Had I predicted at the turn of century that in just two short decades superhero films were to become cultural touchstones of such ubiquity that even politicians and pundits constantly pepper their conversation with casual references to thirty or forty year old comic books . . . well, there are very few quarters of society where such a prediction wouldn’t have been met with baffled incomprehension, if not outright mockery.

It isn’t just that Knightfall was important in and of itself but that the cultural conversation being enacted in these pages still seems very vivid, very real. The questions about masculinity and justice are still asked today, but more to the point they are now often framed in terms of stories like these that were printed and filmed decades ago. Knightfall was the crux of a decades’ worth of changes in Batman, an inflection point where a conscious decision was made to switch up the formula ever so slightly. Those slight deviations in time became huge striations in cultural roadcuts. We live in a world defined and determined by louts at every level of power, unimaginative bullies who whittle every question to a binary referendum on masculinity. In this context the childhood escapism of the hegemon seem significant. What men are and are not allowed to be in their power fantasies seems significant.

When I was a kid there were few things I disliked more than the specious assertion that comic books were somehow “modern myth.” It didn’t make any sense back then because comic book superheroes were strictly a side dish in a very stuffed media diet. It was patently self-aggrandizing marketing copy. But that was before I sat by these last decades and saw the superhero media complex take over the world, and people of all demographics embrace these characters and stories, study and discuss and disseminate them with Talmudic rigor. Then I went to college and studied myth and the history of myth, the practice and social dimensions of mystery cults in the ancient Mediterranean, the significance of oral epic as a vehicle for ideological discourse between generations, and as an idiomatic basis for shared language. Finally I can only ruefully conclude that, yes, superheroes and their ilk have become our modern myths. Their lives and adventures reflect the themes and preoccupations of our own. We have made it so, and the companies that profit from these characters are very happy to comply with our wishes. Human beings like having myths, as it turns out. May god have mercy on us all.

For us - we few, we happy few, we comic book readers - it is incumbent to remember that if these stories remain centrally important to our culture the primary texts will never cease to be significant either. That is how myths work, after all. Why do you think I spent so much time on the numbing minutiae of context, all that thick nimbus of crossover and creator? Context matters, especially in hindsight. Easy to construct a myth after the fact, harder to engage with material nuance. It’s necessary to understand that the important stories were manufactured and marketed and sold and consumed in precisely the same way as the rest of the crap. You never know what funnybook story is going to end up being the rough draft for tomorrow. There are lots published every year, after all. It’s never the ones you think.

Remember that when you next you think on the subject of Batman. He will be with us forever. They will find no shortage of stories so long as we continue to hurt each other fruitlessly. Why, here’s a great idea no one’s ever done: take away Bruce Wayne’s money. Free idea! Make Batman broke for a year. What if Bruce suddenly realized “this is the weapon of the enemy, we do not need it, we will not use it” could also refer to money? Let’s see what infinite prep time can do against poverty and overpolicing in lieu of social services. Might do him wonders to see how the other half live. Maybe then he’d get hep to what the rest of us have known all along, that the true wellspring of great and petty crime that lessens our world resides in the premise that no one would ever choose to live like this - at which point I gestured expansively towards the whole wide world laid at my feet - if they weren’t being held at gunpoint.

The children, attentive through much of my colloquy, began to stir. As gracious as they had been the ruffians did not possess infinite patience, and truth be told many had already wandered off, incensed at my heterodoxy. Not even a token mention of Zack Snyder, they muttered dismissively.

“Well, chee,” the head child mused after I ceased speaking. “Seems to me you may have, ah, fallen behind the times, lady.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, warily.

“Lemme ask,” the urchin said, folding the knife and replacing it in their back pocket, “how many Jokers does this Knightfall have?”

“Only the one, I fear.”

“Hah! Show’s what you know. Bitch they got three Jokers now. Get outta here with that Milt Caniff shit. We will never again be pleased with anything less!”

They began to walk away. However after proceeding fifteen yards they turned back and yelled, loud enough to be heard across the plaza: “You’ll never get rich overestimating the dignity of your fellow man!” With that the youngster ran from my presence, a shark diving through the general tumult of a busy city square. The ruffian appeared for the moment satisfied with their triumph. I resumed my walk.