La ligne claire has not made this much news in Europe for decades. On Wednesday, the Grand Palais opened an epic Hergé expo, which has received only raves from critics and the art world. Its curator, Jérome Neutres, calls it an ambition fulfilled. "Our whole aim is to show that Tintin's creator was, quite simply, a truly great artist. We want to put him on the same footing as a Vélasquez, a Helmut Newton or a Fantin-Latour."

Then two days after the opening, France discovered that Thierry "Ted" Benoit had died. Benoit, 69, may not have been the ligne claire's purest inheritor. But he was certainly one of its great innovators. As the obituaries and tributes to him proliferate, many have begun with similar sentiments. Benoit, they note, was more than just a wonderful draftsman. He was – quite simply – a truly great artist.

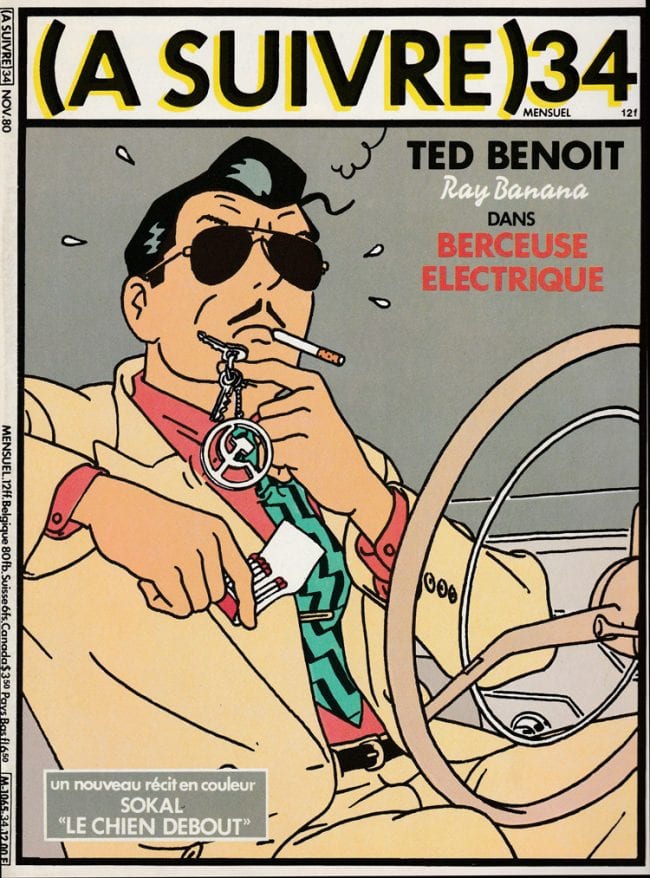

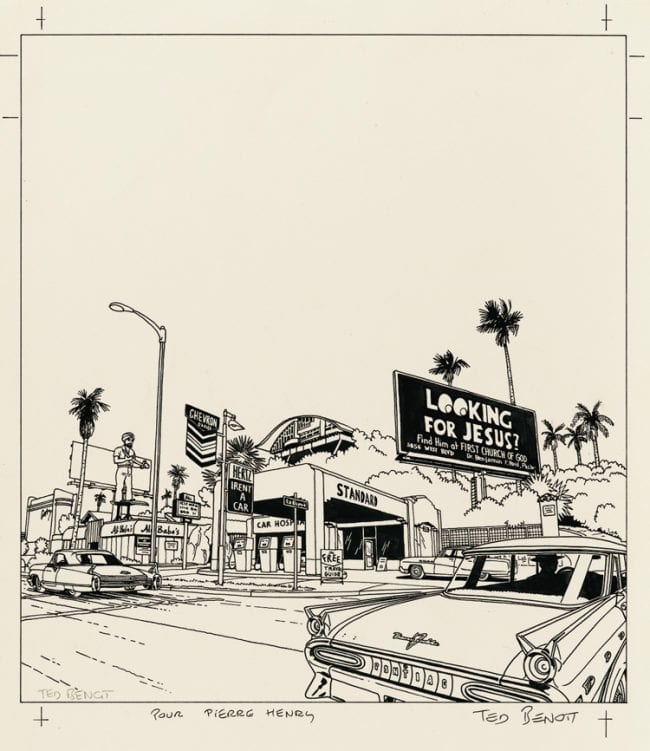

Just like Hergé, Benoit was also beloved. When he created his astonishing character, Ray Banana, the artist fused several French fetishes into one protagonist. The most obvious is an obsession with film noir and the 'hard-boiled' American vision found from Stephen Crane to Mickey Spillane. There's also a very French view of le rock and roll, one whose iconography remains replete with leather, Brilliantine and brothel creepers. Visually, Benoit gave Banana a fixed, unchanging backdrop. It's a particular French dream of the urban filched from Raymond Chandler, Edward Hopper and post-War Hollywood.

All in all, the view is rather sans sourire – unsmiling. Yet Ray was named for the jaunty sunglasses he never sheds.

Initially Benoit hoped to work in film himself. He studied it at IHEC, the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques. Then, until 1971, he worked in television. But, being a fervent fan of Robert Crumb and his compatriots, Benoit soon got involved with French underground comics. By 1975, he had appeared in and worked for Géronimymo, Actuel, Métal hurlant and L’Echo des Savannes. In 1979, he published his debut album – the chilly and expressionistic Hôpital (Hospital). Portraying its central institution almost as a prison, it won Angoulême’s prize for the year's best scenario.

Then Benoit discovered Joost Swarte’s L’Art Moderne, the ligne claire reasserted in flat pastels and pellucid lines. Already known for discreet, fastidious draughtsmanship, the Frenchman found his Dutch colleague's recipe irresistible. In its clarity he sensed an existential elegance – but it was also the perfect vehicle for his stark and stylish world. Ted Benoit embraced the style and he never looked back.

It was in 1980, with La Berceuse électronique (Electric Lullaby), that Benoit unleashed the figure of Ray Banana. Part Clark Gable and part Phil Perfect, this dandy of a certain age stalks streets assembled from every '40s and '50s film Benoit had seen. If you should happen to order yourself a copy from Amazon, here – in the words of one French fan – is what you'll get:

Ever dreamed of being able to live a stunning adventure? Just imagine: your face is hidden behind black shades as you start to drift away, in a melancholy reverie, uncertain what to do with all your mental anguish. Welcome inside the skin of Ray Banana. He's a confusing character, one who marries the mug of Elvis with the viewpoint of a Brussels intellectual. But then you've just entered the subversive world of Ted Benoit. It's one I’ve been unable to leave since my childhood.

By the mid-1980s, Benoit was helping lead an energetic French renaissance of the ligne claire. This was conducted by a varied group, composed of artists ranging from Luc Cornillon and his buddy Yves Chaland – tragically killed at 33 in a road accident – to Jean-Claude Floch and the wünderkind Serge Clerc. Swarte, who actually coined the term ligne claire, christened their emerging new aesthetic atoomstijl or "atomic style". It reminded him of the spunky, Populuxe "style atome" that was pioneered by Jijé and Franquin in the '50s.

The new artists' neo-ligne claire had links to a 'Rock & BD' school of artists (including, in terms of its humour, Frank Margerin), most of whom were resident at Métal hurlant. But their style was soon as visible in illustration as it was in comics. By working for the UK’s Melody Maker and NME, Serge Clerc especially helped it spread into other arenas. But, with the quirky persona of Ray Banana, Benoit kept on pushing the limits of ligne claire in the bande dessinée. There, the world he created was something more than surreal. His Banana sagas do involve noir-ish crimes, but they also feature rock stars and extraterrestrials, religious cults, modern art and Platonic philosophy. In every story, however, the visuals are consistent. All are filled with the '50s cars, cities and clothing the artist loved.

Madeleine de Mille, Benoit's wife, was his colourist. But in 1986, to pay a special tribute, Casterman reissued Ray Banana's Cité Lumière (City of Light). This time, the colour was handled by Studios Hergé. The homage marked a singular thing about Benoit: his talents won over both the hard-core fans of Hergé’s legacy and those who far preferred to follow independent auteurs.

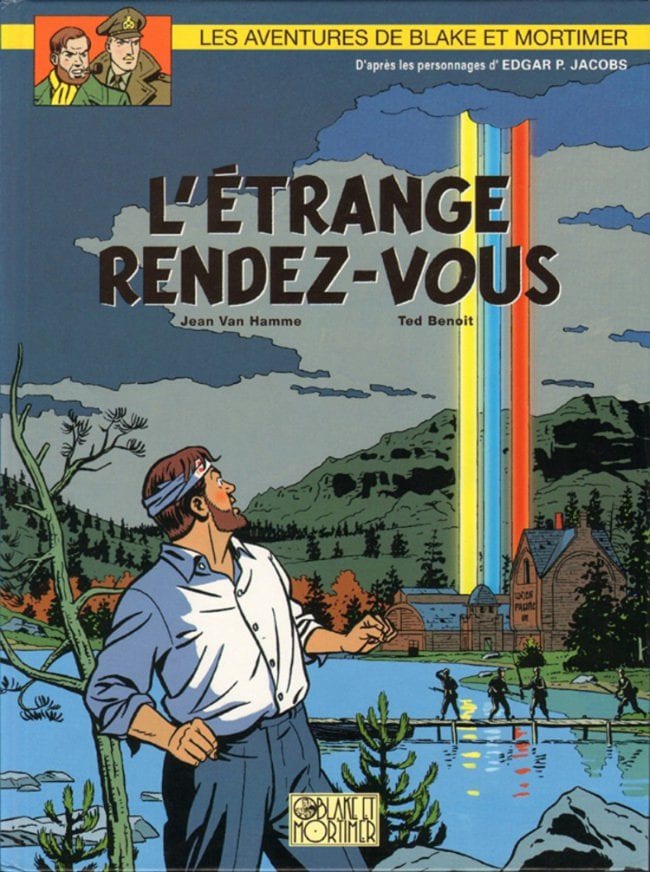

There is another reason the comics world is mourning Benoit. This was his reprise of Edgar P. Jacobs' series Blake and Mortimer. By the mid-90s, when he took up this challenge, it was the equivalent of a Mission Impossible. Jacobs had been Hergé's close pal and sometime collaborator (his bursts of temper helped inspire Captain Haddock). Thus he was a massive and magnificent icon, and one with an enormous, ultra-theatrical talent.

Benoit helmed the series for just two albums: L’Affaire Francis Blake (The Francis Blake Affair) and L'Étrange rendez-vous (The Strange Encounter). Initially, both were heavily criticized. Now, they are seen as probably the finest revivals.

Benoit, who always worked slowly and meticulously, spent four years on each one of the books. He said he found the key to Jacobs' world in its anti-contemporaneity. As Benoit told Le Figaro in 2001, "What I take from Jacobs' own style is all theatrical because, with him, every frame is suffused by the maximal dose of drama. Blake and Mortimer isn't a cinematic BD but a theatrical story. It's the actual dated, bombastic, over-the-top quality – the outmoded grandiosity – which is the very thing that attracts new generations".

At the end of the 1990s, Benoit took up scripting. For Pierre Nedjar, he concocted Le Homme de nulle part (The Man from Nowhere). This was narrated by Thelma Ritter, who is Ray Banana’s cheekily-named cleaning woman. In 2004, having declined any more of Jacobs' British detectives, Benoit scripted Playback – a Hitchcock-style thriller – for François Ayroles.

Benoit then began devoting himself to illustration. He produced advertising, posters and numerous silkscreen portfolios. Like his BD output, all of these now fetch a pretty penny at auction. Yet what colleagues and critics are remembering is a modest man. A trailblazer, certainly. But also, as all of them add, a deeply sympathetic and sensitive man.

Every year, for instance, Ted Benoit would attend Les Rencontres Chaland. Held in the village of Nérac – the town that was home to Yves Chaland – it's a small BD festival which honors his long-lost friend. As it takes place this weekend, wrote the critic Jérome Dupuis, "undoubtedly the event will be plunged into sadness." But Benoit himself, he stressed, will be elsewhere. "He'll be up there alongside Chaland, in paradise".