(Part three of three. Click over for parts one and two)

MAGIC IN HOTEL ROOMS

I'd never got the number to work before and I didn't hold out much hope that this time would be any different. Morrison's Invisibles had nearly wrapped and there were only five issues to go before the final volume's backwards numbering counted down to one and the secrets of the universe were revealed. Right then I was flicking through issue five and feeling increasingly disappointed. It wasn't the story, if by that stage you could even describe the Invisibles as a story anymore, and it certainly wasn't the ideas or the execution. It was something else.

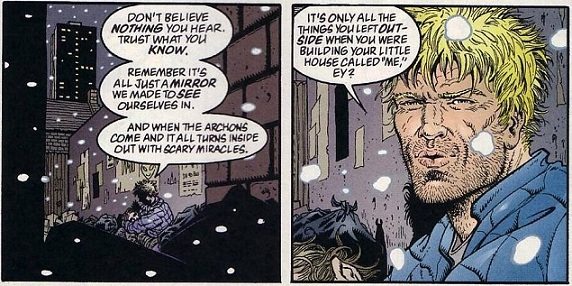

Issue five weaves between a time displaced drug trip and real world events strung together by King Mob's stream of consciousness narration as he attempts to contact the recently deceased Lady Edith Manning from beyond the grave. Very early on he lays out the ground rules.

As is indicated by the content and form of the text (sentences linked by hyphens as opposed to interrupted by full stops), much of issue five relies less on traditional, linear storytelling modes than it does on thematic correspondance, the flow of dialogue and imagery in Mob's scenes obeying a poetic, as opposed to causal, logic - or as the man himself puts it

'-- a join the dots picture -- the invisible emerging as a pattern from nowhere [...] everything is coincidence here -- like the coincidence of the light going on when you flick the switch.'

In other words: synchronicity. For those unfamiliar with it, synchronicity is a term that was coined by Freud's wayward protege Carl Jung, describing 'the experience of two or more events, that are apparently causally unrelated or unlikely to occur together by chance, that are observed to occur together in a meaningful manner' and through it Morrison attempts to make the reader conscious of the immanent interconnectivity of everything. He does this in a variety of ways, but one of the tricks he borrows to make his point is William Burrough's magical number 23. A detailed analysis of 23's strange history in the countercultural books of the sixties and seventies needn't concern us here, but needless to say it's emblematic of synchronicity in its purest form. Once you start looking for it, the stories go, you'll see it everywhere, until the once insane notion that a number can possess a life of its own beyond its inert existence as an abstract mathematical object designed to count or measure starts to seem disturbingly real.

But I'd never got the 23s to work before and I'd been nosing around this stuff for ages.

So, as I said, I was nonplussed that plays on 23 were occurring on nearly every page, even so far as the comic's numbering, issue five, which of course is 2 + 3. If Robert Anton Wilson couldn't activate the 23s in me, and I'd read Illuminatus many times by that point, then what chance did Morrison have? The comic's mission statement, we were told, was to transform the world, and that a consequence of this collapse between the text and the real would be strange, Invisibles related synchronicites in our, the readers, lives. If the 23s don't work now, I mulled mournfully, then surely it was all bullshit? And it had to be bullshit, didn't it?

From the moment I put the comic down the 23s were everywhere. I can't remember many specific instances now, all I can say is I was pleasantly gobsmacked by how many of them showed up. I didn't place much stock in it all, though - it was obviously all in my mind, and while a diverting illustration of the point the comic was making about consciousness constructing meaning and universe, it resonated little deeper than a card trick and would be forgotten in the morning.

Cut to that night, and a friend and I were about to leave his hotel in Tower Bridge for a restaurant on the South Bank, the Invisibles and their quest to save us from the dark forces poised to strange freedom tucked away in the depths of my rucksack and largely forgotten. Nigel, my friend, had one last thing to take care of before we left. He'd forgotten to check whether or not his room was properly alarmed. Nigel has always been a worrier and he wanted to make sure he hadn't overlooked this important detail in the rush to get Bhuna into his belly. At the time I remember feeling impatient with him, only I needn't have worried, he could easily check his security status from downstairs. An LED display in the reception would tell him if his room was unguarded. It wasn't.

I looked up at Nigel, his faced bathed in the eerie red light of the display...

...and the world collapsed.

I tell you, it was as close as I reckon I'll ever come to what it must be like to see a ghost.

ANARCHY FOR THE MASSES

So speaks Jack Frost, breaking the fourth wall and addressing the reader at the end of everything. The message is clear: the story, every story, is always incomplete and defined as much by what it's not as by what it apparently is. Over the course of these essays I've talked about how The Invisibles returns time and time again to the metaphor of things lurking on the outside as a stand in for the denied and forgotten in our own lives and how these things, while alarming in the first instance, can't be ignored because they give shape to our world. I've also been keen to discuss the lesson of deep decentrality this inevitably conveys. Morrison told his readership way back at the comic's beginning that the last mystery to be revealed would be who and what the Invisibles really are. The Disinformation book lumps this in amongst the comic's failures, however its authors' take is simplistic. If you've slogged through what I've written thus far it should be obvious by now that 'the Invisibles' are the information in the gulf between This and That, or as Mr. Six explains in issue five of volume three, the 'space between our fingers'. Their exact nature remains fluid, contigent on whatever This actually stands for moment to moment, but their quality is always the same: ghostly, half-felt, a hazy presence crowding out the edge of vision, like the monsters everywhere but at strange angles to the world in one of Lovecraft's stories. Obviously this anti-matter, this not-self material, could take on trivial aspect, something as ridiculous as 'I am not this teacake', but the comic concerns itself with the times when addressing the divide between self and other becomes urgent. Far from being something overlooked by the author, the question of what the Invisibles are is the key to the whole thing, and by suggesting that a failure to answer it is dangerous - risking in-text injury and enslavement on an epic scale - and by linking this, as Grant does, to the secret of the universe, our universe, this riddle is elevated to the border between a diegetic concern and one we might want to address also.

To be honest this is apparent right from the outset, with or without the knowledge of the author's intended aims. The world of the comic, although fantastical, can easily be mapped across our own - its locations, its politics and its concerns fed by our world, not by the broader vertigoverse within which it was spawned. This is not to say that at the time of publication there weren't other comics under the same imprint dealing with real world issues, there absolutely were, but none more so than The Invisibles. It was a comic always in conversation with society and culture, always talking about something *out there* rather than turning inwards for inspiration. It sought to convey meaningful solutions to the problems we face at the end of an old century and the beginning of a new one. In short it wanted to speak to its readers. But how to get the message out there as something felt, as an unshakable way of seeing? A better example of this fundamental concern I couldn't point to than in the last issue of the comic where Jack imbibes the story in the form of a virtual reality aerosol spray. I'll let King Mob fill in the details.

'The basic fractal generator's pretty simple: yes/no/as above/so below... It lasts for a day and feels like an eternity... It's ragged at the edges but you can play any of 300 characters, some more involving than others. It's a thriller, it's a romance, it's a tragedy, it's a porno, it's neo-modernist kitchen sink science fiction that you catch like a cold.... Couple of the kids who tested it could cure themselves of the Invisibles in five minutes by the end. If you don't get it the first time you have to keep running it. It's different every time. And playing it seems to strengthen the immune system funnily enough.'

The focus, then, in this final piece isn't so much the first part of Mob's pitch - we know all about the comic's focus on the spaces in between by now, its jettisoning of fixed categories and stable narratives - but on that last bit: 'If you don't get it the first time you have to keep running it.' There's always the worry that by the comic's end what the reader will be addicted to will have no real world application: endless attempts to 'solve' the comic. It's all very well reading a story that has personal and political transformation as its focus, only this ceases to be meaningful the minute the reader puts the book down if it goes no further than mental masturbation. As King Mob explains in volume two:

'The most pernicious image of all is the anarchist hero figure. A creation of commodity culture he allows us to buy into an inauthentic simulation of revolutionary praxis.'

Revolution as Duster Jackets and Fluke records on the stereo.

So the part about the comic being caught like a cold, something that acts upon as as much as we act upon it is what I want to address here - where it transforms us and 'strengthens our immune system'. The comic as drug is a visceral description of the effect Grant intends the book to have on its readers. He wants to go beyond the inert passivity of reader and text and see the Invisibles glide through the panels of the comic and into our skin.

THE GATE IS SOFT

Yesterday when a homeless man got on the bus nobody looked at him and nobody 'saw' him. Afterwards most of us probably put him and the monstrous things he represents, old age, addiction, decay, destitution, out of our heads. To all intents and purposes people like him aren't there, they're edited out of our lives and the story of the culture more broadly, but he was there too, and his phantom reek of alcohol and piss. We learn to ignore, to turn off to the thing that doesn't fit, but once you start looking for the ignored, they're everywhere, in everything, the world an invisible kingdom. Grant talks about this general state of denial in Arcadia, the time-travelling second arc of the series, where King Mob explains why even though his team are dressed anachronistically the inhabitants of revolutionary France don't so much as blink at their appearance. By now we're all familiar with the 'we-don't-fit-the-consensus- model-round- here-so-we're-invisible' get-out, but it's directly relevant to what we're discussing here - a few issues earlier a homeless Jack Frost grumbles about commuters ignoring him, and we're in exactly the same, but far more recognizable, far more relevant, territory. Right from the outset Morrison is trying to address the problem of occlusion. And so the focus is always on the outsiders: the homeless, the queers, the poor, young people, ethnic minorities, oppressed workers and the avant garde - the Invisible not just as some theoretical, metaphysical concern, but conflated with the people who have dipped below the horizon in our reality. Sure, Morrison's representations of people belonging to these groups often leaves something to be desired, but it's the focus itself that concerns us here, and it wasn't as though he always screwed up. Towards the end of the second volume Jim Crow, the Invisibles' resident voodoo houngan, provides us with a poetic and insightful example of an Invisible history. He describes a reverse world with a black power base where whites are maginalised and enslaved but where the slaves eventually wrest power from their masters and hijack time machines in order to travel into the past and 'fix things up real good'. Morrison full stops Crow's fable with an image of him burning an inverted American flag asking 'Is this a dream? Is THIS America?'. The lesson is obvious to the hauntologically inclined. There's another story lurking in the wings of the history, a history half there and half not there. Present and not present. Our world is founded on the Black Other, but we have rewritten history without it, and Crow, here representing all people of colour, all ghosts, comes roaring out of the margins of this forgotten timeline to demand our attention. It's such a shame Morrison has recently revised his time travel theories to exclude the possibility of people travelling into the past to transform the future - the endlessly bifurcating stream of hypertime he once championed allowed for so many possibilities, a multiverse of hidden, spook worlds crammed into the space between spaces. But we're a long way away from that here. You try that mono-reality shit on with Jim Crow, see what you get.

Last time I talked about how learning the comic's decentred logic is a lesson its readers can have difficulty shaking off, something that once seen can't be unseen, but I don't know how useful this is in the long run without another component - something that means that even in everyday situations where other life lessons far more inclined to assert themselves, lessons often at odds with those of The Invisibles, lessons far more deeply ingrained, don't, but are overridden by the comics’ supercontextual message instead. How can we see the Old Man? How can we see the narratives we deny? The power embedded in the narrative that is able to convincingly deny and in the denier hirself? The privilege inherent in that, and how limiting this is, how short sighted, partial and incomplete?

How do we become ghost hunters, mediums - sensitives?

First of all we have to believe in ghosts.

Morrison succinctly illustrates this point early in volume one when a prepubescent Lord Fanny meets the ancient Mayan god Tezcatlipoca.

‘Tezcatlipoca, who wears the star of night on his forehead, is the Black Man, the Father of Witches. He haunts the night in many terrible forms. One of these forms is known as ‘Axe of the Night.’ As midnight approaches a strange sound can sometimes be heard, like the sound of an axe chopping at the root of a tree – CHUTT! CHUTT!. Anyone who ventures into the forest at this time will see that the sound is not being made by an axe at all... I knew all the stories. I had known Tezcatlipoca all my life. I truly believed in Tezcatlipoca.'

This is the difference between theory and reality and it is earth shaking, a visitation one can't plug up one's eyes and ears to. Most of the time we know the Invisible only from a distance, we control our interactions with it so it remains little more than an implausible possibility, however there are times when it gets all up in our shit to the extent that it becomes paradigm busting, when it smacks us round the face as opposed to our tentatively prodding it with a stick and scampering away. Obviously it's very difficult for a comic, or any entertainment, to approximate this effect, but Grant tries and in the end I want to argue that the results were fascinating. The Invisibles was a magic comic after all.

But how does one achieve a magical effect? Well, Morrison has a whole bag of tricks to resort to and they're all deployed to a very specific end. To begin with there's the aforementioned reaching beyond the comic. A self contained text, one that doesn't engage the world of the reader, or rarely does so, stands little chance of manifesting anything in the Real. The boundaries have to be loose, 'raggedy', as King mob says - like the soft, permeable lines of Jill Thompson in Sheman, the first volume's arc most explicitly concerned with rubbishing division. This blurring between page and reader is also enhanced by the book's practical aspect. Within The Invisibles there are 'genuine' time travel and astral projection techniques, how tos for spells, thought experiments, signposts to any number of transformative texts and articles on bleeding edge science theory and models for new approaches to gender and self. Whether any of these things are actually 'real' is beside the point, their inclusion, often to the point that without a working knowledge of the ideas involved the comic becomes incomprehensible, points to an extra level of engagement with the text. And not only that, if these things are actually taken seriously and tested then the boundaries become softer still. 'Blood', as we are told at the end of volume three, 'is necessary to effect the intersection'. We need to give the story our lives, our work, if we're to see it enter our own. This heightens verisimilitude and sees the text closing the distance between itself and not-itself. Obviously this was all highly effective - if my experience on the Barbelith message boards and of reading the comic's letter column convinces me of one thing it's that its readership was deeply immersed, nigh obsessed, with its world and, conversely, that it was worming its way into their, our, lives. Many of us, possibly most of us, instinctively intuited its desire to remain unconstrained by its gutters, and we came to feel, often against our better judgment, that it could push beyond them. How many of us took part in the wankathon? More than would admit to it, I'll bet.

I've already mentioned the pesky fourth wall breaking twice so far in this piece. In both instances, two of many, Jim Crow and Jack Frost's speeches represent the point at which the comic turns to face the reader. It's a simple but effective gimmick even after all these years and creates a convincing illusion that the text is entering into a conversation with us even though we know it can't be. Or can it? The difference between these moments in the Invisibles and in Grant's earlier work, Animal Man for example, is that Jack and Jim are actually saying something, and, more importantly, something that actually has a bearing on our reality. It's all very fun and all when Buddy Baker jumps out at his readership, but the effect heads back inwards pretty sharpish after that. It very quickly becomes not about how this exchange affects us but about how it affects him. There's no challenge for the reader there. It's perfectly safe. Entertainment. But when Jack and Jim do it, when Barbelith asks us to 'try to remember' or when we're offered a blank badge at the end of the penultimate episode, there's a different kind of charge. These moments give us something, we're reached out to and expected to respond with something other than 'Gee whizz! Naughty universe touching!'. After the characters have finished speaking, it's on us. And when the comic does 'revert to base tracker' it carries with it something of the dialogue that was entered into - our story and its story intertwined. And each time it performs this trick the address necessarily becomes more personal, our worlds closer. Let's not forget, also, that the comic with its endlessly destructing structure, bounding from porno to kitchen sink modern...whatever, from one reading to another, encourages deep immersion - it's a mystery one falls into rather than follows, the floor constantly being pulled out from one's feet. This is a book designed to haunt. It’s forever inconclusive, every one of its ‘truths' only half-truths collapsing into half-truths, collapsing into... Always pointing to its own absence. And it is absences, with their incessant demand to be filled, that nag, that we can’t shake when we’re at work, washing up or before we fall asleep, not conclusions.

And all of this is part of the comic's slowly escalating unpacking of and focus on the meaning of 'Invisibility' and a corresponding powering down of our cloaking device. As each volume progresses the comic's reality gets softer and softer. At the beginning we’re trapped in a very real war between two opposing armies for the soul of humanity. By the end of volume two, with its constant referencing of Hollywood and Guy de Borde, we’re not sure if we’re watching some kind of grand hoax, a simulation. And by volume three the ‘war’ is resolved into the workings of a giant spell, the characters just glyphs on a page, the events the alchemical formulas connecting them. This softening is accompanied by a necessary simplification of all the elements involved. During the penultimate arc, which sees the Invisibles hijack a ritual designed to draw down armageddon, Jack Frost is provided with a vision of the Secret Chiefs of both the Invisibles and the Outer Church. These beings, we’ve already been told, are in fact the superbody of the entire cast, dynamic triads of structure and chaos pulling the strings of, indeed encompassing, all the comings and goings of the comic. As we head further and further towards this ultra-permeable, unbounded reality where 'all are one and several are none' and where, in Jack's words, 'it's all just bullshit anyway' the next question becomes: Where do we go from here?...

Into the reader, the ultimate Invisible.

Morrison articulates this unity of self and story beautifully in issue five.

This dream stuff, which at every point contains the information of the whole, maps across the qualities of magic matter and our own minds. There are too many examples of this kind of thing to list here, but needless to say The Invisibles is constantly reminding us of the soft boundaries between inside and outside, and from there it's only a short hop, skip and jump from occasionally, for a split second breathtakingly, vanishing them.

Seven years of this x learning it as a mode of reading x reader immersion x the writer catching a life threatening illness from his story and a wankathon improving sales = voodoo comics.

We believed and a two way street was opened up between ourselves and the book.

And it's in this headspace that very weird things can happen.

HOW I BECAME INVISIBLE

At this point I should say that I'm no proselytiser for the supernatural. I grew up around the 'nutrition' industry and around a cult, which means I know better than most how credulous people can be and have no interest in trying to convince my readers of the existence of magic or ghosts. What I do think, though, is that the experience detailed at the beginning of this piece warrants unpacking, particularly in the light of the subject matter of these essays. First contact with fictional reality Grant calls it, but I'd prefer to describe it as first contact with dissolution of the bounded self. I know that this might come across as hippy rambling but in truth I'd regard my 23 moment as the book's primary goal. It represents the proper absorption of its theme of decentrality, and if it failed to achieve it, not as a life lesson from the mouth of King Mob but as an unshakable experience, then it would have failed completely. This is not to say everyone went to *the place*, or that they will, just that it's what the comic's aiming for. And while my experience is only tangentially related to the comic as it is on the page, it needs to be included in any essay because it cuts right to the heart of what the Invisibles is supposed to be and do. If it doesn't happen for them then I believe that many readers will return, frustrated, to the text in order to get there. Because that is what we're being groomed for, what the Invisibles teaches us to expect.

What I find fascinating about this collapse even now isn't that it muddied the distinction between subjective and objective truth, but that it turned me into a function of the text. I became part of the web of coincidences Mob was describing. Part of his spell. Part of the comic's spell. But just one part. One cog. An Ergo. I was abducted by the comic. We've heard about the Death of the Author, but the interplay between reader and text of which this out and out weirdness serves as the ultimate example resulted in its inverse: the Death of the Reader. And why is this useful above and beyond all the pretty flashing lights? Because of what it does to the power dynamic. Anything that decentralises to this degree, that makes us realise that the Invisible isn't simply a footnote in our story, but that we may be a footnote in its - that ghosts us - is massively healthy for a privileged, white heterosexual westerner to undergo. It's sobering. Humiliating. Probably necessary.

Let's face it 'the Reader' at the turn of the new millenium is such a terribly pompous thing, the product of late twentieth century capitalist culture which persuades us we're all tiny, untouchable gods beyond the veil of whatever it is our perfectly formed critical judgment is seeking to praise or damn, to objectively assess, today - whether or not it's a comic, a film, the state of international aid or dole scum. Our opinion has so much value, it needs to be heard - if not why is it that it can be heard, so loud and so clearly? If the reader is the ur-text then it is the final Buddha's head for King Mob to put a bullet in. The site of the last detournement. I've mentioned already the final phase of Jack's initiation, his imbibing of the Invisibles game, but I skimmed over the most important aspect of it - the strange loop it initiates in him. After all, how can one imbibe one's own life in a can? How can one's 'days' lead inevitably to that same inbibing.... Where does it end? When did it start? Reality and fictive reality become sticky, muddy, impossible to separate out or arrange into rigid hierarchy. The next step for Jack is clear, if he wants to free himself from the program crash caused by this collision he needs to jump off the board, the page, and into the reader, but.... let's not get ahead of ourselves, that's the end, when the show closes - it's the stickiness that concerns us here, Jack's in-panel predicament echoing the final predicament Grant desires the comic to place us in. The place I got to. Jack the Reader locked onto the text, locked onto Jack the Reader.

And of course this scrambles time. If it didn't then how is it that the 23 and the comic managed to hijack all the events of my life up until that point in order to manifest there, on that LED screen? Like Jack I was left asking, where did this begin? Where does this end? Where do 'I' end? Afterall, you thought the Reader was You, but the Invisibles have a very different conception of 'You', an entity that is 'billion eyed and billion limbed' - the Reader smithereened into everyone who comes into contact with the comic. This is the 'Zen Fascism' Morrison made so much of at the time, a unity of not-thisness, the unity that is a plurality. We're all ghosts together, in a condition of permanent marginalia, endlessly receding into the distance like Jack's vision of the time-worms at the end of volume three.

Last year at the end of Brighton Festival I watched Brian Eno give a talk about art and its place in society. Although very interesting in places and highly entertaining, for a variety of reasons it wasn't very good. Nowhere near as nifty as the Long Now lectures I'd heard online. I remember one part of it stood out because it seemed so obvious to me, where he talked about how art is a safe way of rehearsing new ideas and possibilities. Well that's how I see my 23 experience. It isn't the same as incorporating the (un)reality of the homeless man on the bus, but it's on the same continuum. A harmless, although shocking and memorable, way of approaching a more accommodating outlook. A house in which, as King Mob says when discussing his detonation of Mason Lang's mansion and the possibility of his building a new one, we all can live.

One of the problems more literalistic readers have with the comic, those people who confuse it with a Sherlock Holmes novel and spend all their time looking for answers and clues, is that it can never come out and declare its secrets on the page. The Invisibles talk about a 'twilight language', an uber-sprech where 'vowels unfold into higher dimensional forms, double eyes and tripleohs... compressed consonants.. sess and ateh....', an alien language which describes reality as a whole as opposed to atomising it like our own. Sadly we don't have a language like this. There is no language, no common way of seeing, accomodating both plurality (the vowels - the inbetween bits) and division (the consonants - the boundaries). Attempts have been made in everything from Rastafarianism to Queer theory to arrive there, but we're a long way off yet. The range of experience described by the Invisible, whilst everyday and always immanent, is probably easier to convey in metaphor, story structure and magical effect than it is in words. This is why I've chosen supernatural visitation as a way into these essays, because I needed a lens which captured a liminal reality, an 'impossible' reality beyond the borders of consensus and most of our abilities to properly articulate. Derrida, hauntology's originator, always struggled to convey his meanings because his project of decentralisation and deconstruction was about the limits of language, and maybe this is why raw experience, regardless of whether or not there was any 'truth' to it, might be the best and last thing The Invisibles can offer us. The raw experience of the inbetween. And an experience always rooted in and directly spinning out of the, in the end almost disavowed by the author but nevertheless everpresent, political concerns - the life concerns - represented in the comic, so never divorced from the meaningful.

EDITH BEING DEAD IS LIKE SOMETHING BEING BORN

'What I know is this: unusual information and insights seem to download into the brain... A kind of ego annihilation is followed by a euphoric reintegration and extended understanding. There's a surge of creative energy, all time is understood to be happening simultaneously, weird synchronicites occur constantly. A new relationship with time, the self and death... But it won't necessarily do you and good if you're attacked by a lion or a VAT inspector.'

King Mob working hard not to over egg the pudding. In the end we have to live in the world, the dissolution I've discussed above recombining into a person who has to pay hir bills on time, but a person, perhaps, with a broader outlook. A person possessing, metaphorically speaking, a strengthened immune system, able to, in Jack's words, 'make friends with [their enemies] [...], till they beg for mercy'. Someone sensitive to and able to process difference. This is why the comic is 'a mirror we made to see ourselves in', because in the end what it's intended to reflect isn't a person singular, but the whole of the comic's cast, both on page and off. It addresses us as dynamic beings, a vast bio-plasm, in constant conversation with itself. And then it asks us to cure ourselves of it, to put it down and get on with our lives, more whole for having been destroyed. And not in some nasty self help way - simple ego reinforcement - but as someone who recognizes themselves as part of a wider community, both internally and externally. But just one part. An example. An Ergo.

The cover to issue five depicts a woman's eye surrounded by a swastika of arms. At first glance it appears terrifying, a vision of one of the Lloigor from an H.P. Lovecraft novel, but reading the comic we come to realise that this image could equally describe Edith beyond the grave. There's often this tension in the Invisibles when its characters are confronted with the beyond. Miles tells us right at the start of the countdown that 'Man will not be man... He will be like them... Star-headed in the... 2012... The trans-continumm.... [....] like the Old Ones! Like them!' and ultimately we know its simply a question of perspective. Is the Invisible Kingdom a nightmare death-camp forever, or is it eternal freedom? It's only at the start that these things feel eerie and monstrous. When we're scared of the Invisible. When we want to shut our eyes and our minds to it. That's when we're haunted by the forgotten ones and the abject terror of quashed hope for the future. Hauntological art is never intended to be passive, it always wants to shake the reader up by ghosting itself with its own absence. It always wants to point to the crack in the pavement and ask, when did that happen? What died? What it doesn't do, what's beyond its remit, however, is the offer of hope, which is fair enough, seeing as it sets out to disturb. But one of the things I prize about Morrison's comic on the other hand is the way it sees its denizens diving into these absences to discover what lies beyond them, to see if they can assimilate them, to process and sublimate the disjointedness of things into transformative action. In the end everyone does it, from John a Dreams plunging headlong through the door to Universe B, to Lady Edith on her death bed slipping away into an ECT fracture travelling up her hotel room wall, and finally, Jack, passing into the mirror on coronation day as the sun transforms into a radiant black hole - the same metaphor, the same desperately brave act returned to again and again.....

And, beyond, the mirror's shimmering surface liquefies, tidal crashing on the shore of a beach.

POSTSCRIPT: The other day Nigel and I were talking about a meal my brother and I went to when we were ten or so. We'd told him about the videos my father had seen of soviet 'psychics' allegedly bending metal with their minds. This spurned Nigel on to ring ahead and get the proprieter of the restaurant, a woman he was friends with, to bend all the forks on the table before we arrived so we'd believe the game we'd played on the train where we used our mind power to bend the metal from a distance was real. For something so obviously mind blowing it was weird that it'd slipped right out of my mind... and it got me to wondering. Perhaps I'd mentioned the 23s to Nigel at some point over the course of that day. Maybe it was all a trick. The guy loves a good trick.

I got to wondering.

And then my housemate's (not)boyfriend leaned over my computer as I was hammering away at my second piece and the stuff about Jack Frost, the Invisibles' very own avatar of Horus. 'What's this?', he asked, pointing to a photo in his mythology book.