When the scenarist René Goscinny (1926 – 1977) died at 51, much of the world felt they knew him. With Astérix, he had created a hero who outsold Tintin. Yet Goscinny had also helped to found and run Pilote, a magazine often described as "MAD à la française". It was Pilote that won French cartooning back an audience – adults – that it had lost after the 19th century.

Forty years after Goscinny's death, two Paris shows are remembering him. One has taken over the Cinemathèque Française, the other is at the Museum of Jewish Art and History (mahJ). Goscinny and Film is a romp about his love for movies, but Goscinny Beyond the Laughter at the mahJ is more. It looks behind the author's orderly CV and discovers years of isolation and frustration. Two things helped Goscinny surmount his frequent setbacks: the outsize expectations he created for himself and his absolute refusal to surrender.

When he began as a scenarist the role was shabby. Those who scripted comics were not mentioned in contracts, they were badly paid and rarely credited. But his enormous talents turned it into a real profession and, eventually, they also made him famous. Goscinny stuffed his scripts with what the French call "second degree": puns, wordplay, double-entendres, cultural jokes and subversions. The comics expert Jean-Pierre Mercier contends that his use of subtext "has taught generations how to critique the media."

Although he employed every kind of stereotype, Goscinny's favourites were French. Most of his fellow countrymen see themselves in his work and, almost always, they get a kick out of doing it. Astérix may be a global symbol of "Frenchness" but his adventures are far from being nationalistic. What they really mirror is a French conviction – that life is best navigated with wit and sociability.

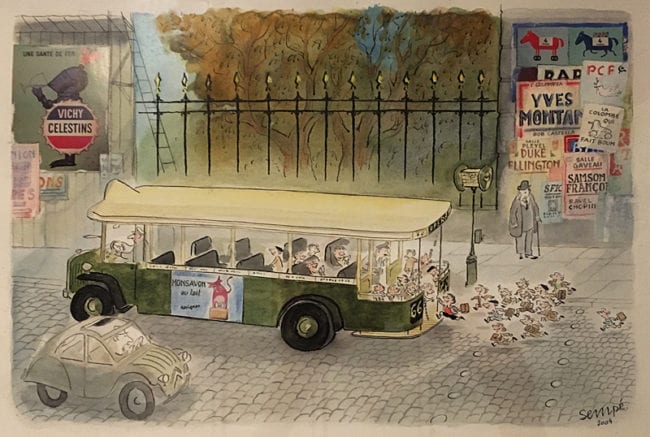

Astérix was not Goscinny's only hit. Between 1955 and 1962, he produced three more series that were – and remain – enormously popular. Each of these was created with a different partner. The first, Le Petit Nicolas, is life seen through the eyes of a schoolboy. Invented by artist Jean-Jacques Sempé, the character name was named after a local wine merchant. From 1956 to 1958, Goscinny and Sempé's stories ran as a weekly strip; after that, they became a set of books.

By 1955 Goscinny was also the writer of Lucky Luke. Created in 1946 by Morris (Maurice de Bevere), Luke was Spirou magazine's old-fashioned cowboy. But once Morris ceded his story to Goscinny, the character became what Pascal Ory calls "a model of sang-froid, quicker with a riposte than a slug or bullet."

Less well-known outside Europe is Iznogoud (pronounced, in French, "Eez-no-good"), who was conceived in 1962 with Jean Tabary. Pint-size and choleric, Iznogoud is the "Grand Vizier" to Baghdad's Caliph – a superior he is constantly scheming to replace. "Iznogoud has every fault," Goscinny once said. "He laughs at the values of others; he's greedy, crude and criminal. But he makes people laugh… so he's a hero." In France the character's catchphrase, Je veux être calife à la place de calife! ("I want to be caliph instead of the caliph!") is still shorthand for indecorous ambitions.

Astérix, Nicolas, and Luke are read around the world. Yet, in many ways, Goscinny's greatest achievement was Pilote. Under him, between 1963 and 1974, the magazine transformed Francophone cartooning. As its editor, he helped comics become adult entertainment and consolidated the idea of a BD "auteur." When Goscinny started, says his Pilote successor Guy Vidal, bandes dessinées were seen as "something for children or mental defectives." He brought the form respect – as well as 1.5 million readers every week.

As an editor, Goscinny also revealed the rarest of qualities: he was willing to back work he didn't actually like. The list of artists he encouraged is enormous and it includes Gotlib, Jacques Tardi, Enki Bilal, Annie Goetzinger, Phillippe Druillet, Jean 'Moebius' Giraud, Claire Brétecher, Alexis and filmmaker Patrice LeConte. There are also notable non-Franco-Belgians such as Robert Crumb, Hugo Pratt, Frank Bellamy and Terry Gilliam. It was Pilote "graduates" who, during the 1970s, finalized comics' new status by founding L'Echo des Savannes, Fluide Glacial, and Métal hurlant.

Goscinny worked with Harvey Kurtzman and André Franquin, Will Elder and Albert Uderzo. He was in Argentina for Dante Quintero's Patoruzú and in Manhattan when his friends launched MAD.

From the age of twelve, however, he wanted to be Walt Disney. Unlike millions of other such dreamers, he achieved something like it. In 1973, with Albert Uderzo, Goscinny resuscitated the French animation industry. The two fathers of Astérix founded their own studio, one whose MGM-like logo featured his cartoon puppy Idéfix ("idée fixe"). To help them with staff, the French government founded an animation school. Forty years later, this same institution – Les Gobelins – is turning out stellar graduates from animator Pierre Coffin (Despicable Me) to artist Bastien Vivès.

René Goscinny's face was famous all over France. A popular guest on radio and television, he created (and starred in) the sketch show Microchroniques. The writer appeared on magazine covers and dined out at glamour spots. In both Paris exhibitions, whether his photos show a pudgy infant or busy executive, there is a smile on his face.

Yet behind this omnipresent grin lies a troubled story. As one of his biographers writes: "If all the talent came out of broad experience, it also came from his fearlessness in the face of serial failures and years of defeat."

Goscinny was born in Paris, to a father and mother naturalized fifteen days earlier. Both of them were Jewish immigrants. Stanislas Goscinny had come from Poland and his wife, Anna Beresniak, was part of a Ukrainian family with nine children. Beresniak & Sons, their Paris print works, was unique. It published everything from Zionist tracts to socialist papers and worked in five languages: Yiddish, Hebrew, French, Polish, and Russian.

Before they met, Stanislas held jobs in Mexico and Tunisia. A year after René's older brother Claude was born, he took his family off again – to raise bananas in Nicaragua. Only when these efforts failed did he return to Paris. By the time René arrived, Stanislas was employed at the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA).

Formed to save European Jews from persecution, the JCA helped them settle in Latin America. This was why, from the age of two, René grew up in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Every three years, however, the Goscinnys returned to France. These special vacations, each six months long, helped make René's birthplace seem magical. ("For me the pampas and the gauchos, those were banal. France was the exotic! Just a word like moulin [mill], that was exotic!.. Louis XIV saying I am the state… that was fantastic!")

But his French fantasy was also a source of anxiety. As an adolescent, Goscinny drew compulsively and many of the caricatures he did feature Nazis. On display beside those sketchbooks are family letters. "With what is now happening in France," writes an uncle, "we do not have any idea what will become of us."

The year Goscinny turned sixteen, everything in his life changed. Anna's father and mother, refugees in the south of France, died within months of each other. Three of his uncles were interned, then killed at Pithiviers and Auschwitz. Anna's brother-in-law met the same fate in Poland.

Seven thousand miles away, the 17-year-old was receiving his baccalaureat. He had plans to join De Gaulle's Free French in London. Then, two weeks later, 56-year-old Stanislas died of a cerebral haemorrhage. He left the family almost penniless.

Claude was aiming to enter Harvard, so it was Anna and René who went to work. His mother became a secretary while Goscinny did accounts for a used-tire company. They were in touch with just one family member, Boris Beresniak, who was working in New York. Boris urged the family to join him and, in 1945, Anna and René agreed.

Goscinny expected a Manhattan filled with movies and jazz and the lack of glamour unsettled him. "I had arrived from Buenos Aires – a comfortable, modern city. New York seemed old and squalid… far from the world of Fred Astaire." As he struggled to learn English, the 19-year-old worked at a small Moroccan business.

One day, three FBI agents arrived at their office. Representing America's army, they made René an offer. If he joined the army, he would become a citizen. But if he refused, he would have to serve in France. Goscinny and his mother scraped together his fare to Marseille.

Post-War France proved another shock. "The country is simply a set of ruins," Goscinny wrote his mother. There was so little food he lost almost fifty pounds. But the trip reunited him with the family in Paris, where Serge Beresniak had relaunched the print works. Obligingly, Serge produced an individual order: a Balzac novel "illustrated" by René. Armed with this precious proof that he was already published, Goscinny rejoined his mother in Manhattan.

Although he was finally "home," René was lonely and friendless. For eighteen bitter months, he was also unemployed. The mahJ show features a snapshot version: his neat letters of enquiry hang next to their curt rejections. But, in 1948, Goscinny met Harvey Kurtzman. Kurtzman had started the "Charles William Harvey Studio" and, before long, it was serving as Goscinny's "office."

Four years after setting foot in Manhattan, René had only one form of steady income. This was postcards he hand-painted at home, as piecework. Then Kurtzman found them work with a children's publisher, Kunen. The same year, Goscinny met Belgian artists Jijé (Joseph Gillain) and Morris (Maurice de Bevere). Both of them lived in Connecticut yet they worked for Spirou in Brussels. Along with the Kurtzman crowd – John Severin, Jack Davis, Wally Wood, and Will Elder – it was friendship that saved Goscinny's sanity.

In 1950, Jijé introduced him to the entrepreneur Georges Troisfontaines. Expansive and determined, the visiting Belgian owned a pair of media agencies. One of these, World Press, supplied cartoons to Spirou publisher Dupuis. Over cocktails, Troisfontaines gave René a card and told him to stop by if he was ever in Brussels.

Less than a year later, Kunen Books went under. Although Kurtzman had already started Two-Fisted Tales, Goscinny was left unemployed again. So he created a comic of his own: Dick Dicks, the story of a maladroit detective. Goscinny sent his finished boards to Jijé, who was back in Belgium. But months and months dragged by and, finally, they came back in the mail.

Goscinny had literally one card left. He re-drew his storyboards, said goodbye to his mother and sailed for Belgium with Troisfontaines's address. It was a desperation gamble – but it worked.

The World Press boss had no memory of René. He shook hands, shared a joke and vanished, telling assistant Jean-Michel Charlier to show him out. But Charlier, taken with Dick Dicks and its author, somehow persuaded his boss to hire Goscinny. Within a year, this "native Parisian" was sent to their office on the Champs-Elysées.

For anyone of Goscinny's age and ambitions the moment was perfect. Belgium, the home of Spirou and Tintin, led Francophone cartooning. Plus the market depended on agencies like Troisfontaines' World – they furnished almost every magazine with content. The company's Paris office ran on a shoestring but it was a high-spirited, collegial spot. At Paris World a "day's work" also involved bars and nightclubs, which helped to bond its young, male staffers. There, although Goscinny was fast friends with Charlier, he became even closer to another colleague. It was Albert Uderzo, who was the son of Italian immigrants.

The pair worked together on the girls' weekly Bonnes Soirées. René masqueraded as "Liliane d'Orsay," the magazine's demanding Miss Manners. He penned her advice column, which he detested, for almost five years. The duo's other collaboration was a marital sitcom, the illustrated column His Majesty My Husband.

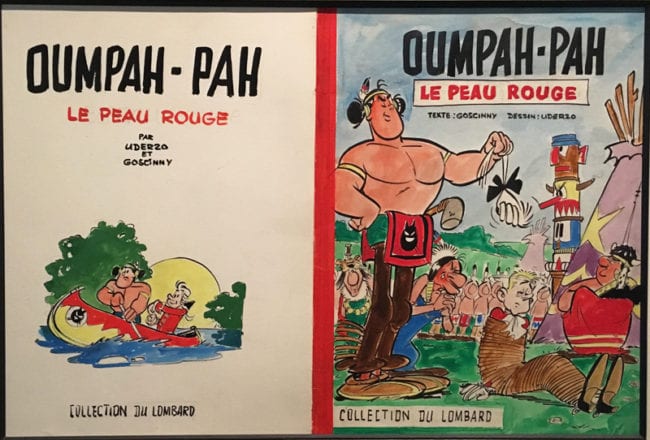

World Press had no actual interest in Dick Dicks, which they eventually sold off to a socialist weekly. But Goscinny and Uderzo had their own ideas. Together, they created a strip called Oumpah-Pah, whose protagonist was an American "Flatfoot Indian". Oumpah-Pah's creators hoped to see it in Spirou, but their offering met with a swift rejection. Oumpah-Pah would wait seven years for publication.

But these were mere stumbling blocks; Goscinny had found his niche. Until, in 1952, Troisfontaines sent him back to Manhattan.

There Dupuis was launching a US weekly, TV Family. In Europe, broadcasting still meant radio but, in America, television was a phenomenon. Troisfontaines saw it as a potential jackpot. Officially Goscinny was just his magazine's art director – but in fact he was the only staff member who could speak English. Having agreed to take the job so he could see his mother, René found himself running whole operation. It included many all-nighters at the Connecticut print works.

TV Family died after only fourteen issues. Dupuis had sunk $120,000 into the effort and no one at the firm ever mentioned it again. An exhausted Goscinny slunk back to Paris.

There, in a busy world plagued by tardy authors, his scripts began to be noticed. Not only were they inventive and impeccably typed – Goscinny's scenarios were always on time. His return to Paris also brought new projects. He and Uderzo began again with Jehan Pistolet, a tale about would-be pirates set in the 18th century. Charlier tapped him to co-edit a weekly – Le Journal de Pistolin, owned by Puplier Chocolate.

Just as things were looking up he was reassigned to New York.

This time Goscinny was sent as a correspondent – charged with finding and translating American work. He was also meant to sell World Press compilations. But René sold just two, collections called French and Frisky and Cartoons the French Way.

Within a year, he was bounced back to Paris, bringing Anna – now 66 – to live with him. Although his third New York stay was yet another failure, Goscinny had managed to reconnect with Morris. As a result, he was now writing Lucky Luke. But the assignment was secret and he got no credit. (He would wait seven years for a byline on the strip, during which he penned nine bestselling albums.)

At World Press, Charlier and Uderzo now wanted a union. Although the employees at magazines had author's rights, agency staffers like them ceded everything. Goscinny helped organize the creators – he was in charge of meetings – while Charlier created an 'Artist's Charter'. But, somehow, Troisfontaines got wind of their efforts. The boss called Goscinny in and fired him on the spot. Charlier, Uderzo, and their colleague Jean Hébrard resigned.

Troisfontaines put all four troublemakers on a blacklist. For two years, officially, they were excluded from mainstream publishing.

It should have been a death blow. But it was now that Goscinny's hard-luck years paid off. When Hébrard unexpectedly came into a small inheritance, René persuaded his pals to found their own agency. They called the company "EdiPresse-EdiFrance." It was limited to working with fringe companies, firms that made hair cream, margarine, or chocolates. But, very slowly, being artist-run paid off.

Now that Goscinny had no ties to Spirou, for instance, the magazine's archrival Tintin decided to benefit. Despite the ban, Tintin established contact right away and, within a year, Goscinny was one of their pillars. Far from languishing on the sidelines, he was now writing for stars – names like Franquin, Macherot, Berck, Tibet, and Bob de Moor.

Three years into the EdiPresse adventure, Jean Hébrard ran into a school friend called

François Clauteaux. Having made it in marketing, Clauteaux was about to realize a long-term dream. It was a "Paris-Match for young people" he called Pilote. Because the juvenile market in France was ruled by Spirou and Tintin – both created in Belgium – Clauteaux knew there was room for Paris-based competitor. Impressed by Hébrard's team of artists, he gave them the project.

The quartet put Pilote together in less than a year. Its sole sticking point was a certain "historic strip." Goscinny and Uderzo took responsibility for it but, only months before the launch, they were still struggling. The pair had already tried – and shelved – a medieval animal fable1. Now slightly desperate, they holed up at Uderzo's flat. As their afternoon drifted by in a haze of Pastis, Goscinny posed a question: during what historic period had France become "French?" Probably in prehistoric times, laughed Uderzo, or… maybe under the Gauls. Goscinny seized on his words. "Within fifteen minutes," says Uderzo, "we had our whole story."2

With Astérix on its cover, Pilote was launched on October 29, 1959. The character's creators had spent eight years at work together, during which they collaborated on numerous strips: Oumpah-Pah, Jehan Pistolet, Luc Junior, Benjamin Benjamine, Bill Blanchert, Poussin et Poussif, Le Famille Cockalane, and La Famille Moutonnet. Most of these went nowhere, but this time was different.

It is now forty years since Goscinny's death and five since Uderzo retired. But Astérix is booming. In 2017, more French residents purchased bandes dessinées than at any point during the previous decade. Of those record sales – 43 million – the latest Astérix album accounts for fully one twenty-fifth.

The series achieved its status with a record speed. In France, the initial album (1961's Astérix the Gaul) sold 6,000 copies. But after that, sales ballooned with every book. In 1962, for Astérix and the Golden Sickle, they reached 20,000; in 1963, for Astérix and the Goths, 40,000. A year later, Astérix the Gladiator sold 150,000 – and, from there, the figures continued to go up.

Pilote was not as quick to establish an identity and, despite the success of Astérix, it had financial problems. In 1960, it was saved by Georges Dargaud, who bought the weekly with one symbolic franc. Yet Dargaud, who was Tintin's French publisher, had his own weak point – and it was editorial. Rather than focus on comics, he centered Pilote on television and yé-yé music. His decisions only deepened the damage and, by 1963, Dargaud had lost his interest. In a last-ditch gamble, he put Goscinny and Charlier in charge.

They gave him the most important title in French comics history.

Goscinny's perspicacity as an editor is still startling. As Pascal Ory puts it, "He didn't discover the stars of his era, he discovered the stars of its future." One of them was Métal hurlant's co-founder Jean-Pierre Dionnet. Dionnet joined Pilote when he was 21 and he sees Goscinny as one of a kind. "Maybe because he worked with all of those New Yorkers, Goscinny knew how to address the largest public possible. He also understood how to manage young auteurs. He knew exactly what to do and when to overlook our faults."

But employees like Dionnet saw him as someone from another age. Fast approaching forty, Goscinny spoke to them using the formal "vous." He never shed his suit and tie and had no visible girlfriends. He was also devoted to fetishes from the Fifties: Pall Mall cigarettes, Waterman pens and his treasured Royal Keystone typewriter. He still lived almost next door to his aging mother.

Pilote's artists knew nothing of Goscinny's early struggles. But they all discovered how much he prized control. From his meticulous desk to his punctilious manners, everything their editor did and said was formal and "professional." This order and discretion, however, masked a deep timidity. Still anxious about his talent, Goscinny was sensitive to any kind of critique.

In 1965, on a cruise, the editor met a pretty brunette called Gilberte Polaro-Millo. Gilberte was sixteen years his junior and a Roman Catholic. She knew nothing about the media and had never read comics. Yet on April 26, 1967, she and Goscinny were married. From New York, Harvey Kurtzman sent him a telegram: "I don't believe it! I don't believe it! I don't believe it!"

His wedding was the summit of a landmark year, the one in which an Astérix album first sold over a million, the one in which René was made a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres, and the one when Georges Dargaud put him in charge of the company. The following May, Gilberte Goscinny gave birth to their daughter, Anne. She arrived in May of 1968 – just as France changed forever.

Even fifty years later, no one can agree what "May '68" really means. But its series of student demonstrations truly exploded. They spiralled into the largest general strike in French history and, by summer, there was a genuine national crisis. It came complete with tanks in the suburbs and real fears of a revolution.

The moment was one of high hopes and explosive anger, with grievances being aired all over France. As Jean "Moebius" Giraud said thirty years later, "There was a deep desire to change everything fundamental: relations between men and women, relations with one's family, relations with work … there was also an urge to change what music and art could be. We wanted so many different things, we could never have listed them… some kind of Big Bang was simply unavoidable."3

It happened at a "meeting" famous in comics history. Goscinny's artists summoned their editor not to the office, but to a local brasserie. In order to get there, he crossed the broiling, strikebound city on foot. When Goscinny finally arrived, sweltering in his suit, he was attacked, vilified and insulted for several hours. Many of those present didn't actually work for him. But that deterred no one from mauling a "bourgeois boss."

Goscinny's ordeal is notorious. In 2015, it even become a comic called Pilote: La Revolution BD. Created by Eric Aeschimann and Nicolas Bidet (Nicoby), this is based on interviews with six of Pilote's surviving stars: Philippe Druillet, Claire Brétecher, Gotlib, Fred, Nikita Mandryka, and Moebius.4 At the time, all the interviewees were in their seventies – and all regretted the incident they termed "violent," "hurtful," and "awful."

There was reason for remorse, because Pilote had been its own revolution. Says Eric Aeschimann, "The basics of adult cartooning were already in place, everything from psychedelia to news as humor… Pilote was the only magazine to grow up along with the readers." In achieving this, however, Goscinny drew together very different artists. While some were content to provide classic fare, others were determined to destroy every boundary. Only one thing held them all together: him.

Moebius was one of his most unforgiving critics. Yet, as he remembered in 2007, "Things only went as far as they did because he seemed so strong. He took all the pressures of that era on the chin. We all expected an angry response and lots of argument. But that wasn't Goscinny; every attack just hit him harder."

When the tirades ended, their editor stood up, said a couple of words and left. Once home, he called Georges Dargaud to say he was quitting. Dargaud refused to accept his resignation, but René remained livid. For days, Goscinny simply railed against the whole profession. It was twelve years exactly since he was fired from World Press.

Weeks passed before the editor reappeared. But, when he did, it was clear he had been paying attention. At a tense meeting attended by all staffers, Goscinny announced a total redesign. Pilote would now feature fifteen pages of news – and all ideas for them were going to come from the artists.

His redesign vastly accelerated the pace of innovation and the next few years were Pilote's most productive. But something had been broken. "In order to accommodate us," said Moebius, "Goscinny had to become neither one thing nor the other. To get us what we wanted, he fought Dargaud like a dog. But he had been rejected by his artists, his brothers-in-arms… It must have brought him the most terrible suffering."5

In 1972, Pilote's Nikita Mandryka drew a "zen" episode of his strip Le Concombre masqué. This featured his vegetable hero – the 'Masked Cucumber' – meditating as he watched a field of motionless rocks. The rocks, Mandryka told Goscinny, were "growing." When these these static pages were rejected, Mandryka saw red. He quit the magazine in a huff to found his own publication – and he took Gotlib and Claire Brétecher along with him. This trio launched L'Echo des Savannes.

"After May of '68," said Moebius, "we had all made peace. But L'Echo des Savannes was really a terrible moment. Suddenly, May '68 seemed less of an aberration than it did the beginning of the end."

By the mid-1970s, there were other changes. With the new Charlie Hebdo, Goscinny lost the satirists Cabu, Gébé, and Reiser.6 L'Echo des Savannes had also unleashed ambitions that rapidly led led to other rival titles. In 1974, Dionnet, Druillet, and Giraud founded Métal hurlant. In 1975, Gotlib started Fluide glacial. But, around all of them, the marketplace had changed. Comics were now firmly established and, with their market booming, both artists and publishers started to drop the magazine format. Albums had always been more cost-effective and ambitious artists now saw them as the bigger canvas.

With a plummeting readership, Pilote was forced to address this change. On June 5, 1974, the weekly became monthly – a winning strategy that shored up the statistics. But the decision came too late for Goscinny. That August, with Studios Idéfix up and running, he handed the magazine back to Georges Dargaud.

Goscinny never gave up creating a weekly strip. But, more and more, he saw himself as a man of the cinema. Since 1964, he had been working continuously in film and television. By 1977, his name was attached to a movie (1972's The Annuity) and four successful animated features: 1968's Astérix and Cleopatra, 1971's Daisy Town, 1976's The Twelve Tasks of Astérix, and 1977's Lucky Luke, Ballad of the Daltons.

Finally, he had become the French Disney.

Then, 10am on November 5, 1977, a taxi dropped both Goscinnys off at his cardiologist. Suffering from angina, the writer needed evaluation in the form of a "stress test." As Goscinny started to peddle on the cycle, however, he complained that his arms and chest were hurting. Asked to carry on "just a few more seconds," the scenarist collapsed – and, because it was Saturday, no one else was present. There was no emergency aid, no defibrillator, and, by 10:30 that morning, he was dead.

Artists still joke about Goscinny's "final gag." But the death made him mythical in a new community. Within months of his demise, a book called Transform Death (Changer la mort), referred to it as "murder by medicine." Out of 13,360 stress tests carried out that year, there had been not just one but a pair of fatalities.

René Goscinny's death transformed French medicine; the circumstances that combined to kill him are now illegal. Cardiologists who don't know "Goscinny" is a name still recognize the word. But, for them, it is the synonym for malpractice.

The man who bore it often had as little control over his life as he did over its end. His own father's nomadic life and unexpected demise dictated how the young René grew up. That New York he idolized for its possibilities trapped him for years in a life of terrible solitude. While the friends and colleagues around him flourished, he was seen as a failure. Even when his vision succeeded in transforming a medium, those artists who profited the most turned against him.

His two Paris shows are remarkable for the art – they contain room after room and board after board by great cartoonists. There is work from Franquin, Kurtzman, Morris, Uderzo, Brétecher, Sempé, Jean Tabary, and more. But their every frame was animated by Goscinny and, without his genius, none of them would exist.

Thirty-three years after they first met, Harvey Kurtzman reminisced about his friend in The Comics Journal. "René was one of my best friends," he told Kim Thompson and Gary Groth, "and he failed at everything he did when he lived in New York... The thing that was peculiar to René was that he had this nonstop flow of droll humor, he would just go and go and go and keep up a running monologue. You'd start to feel sleep overtake you purely from listening… But he was good, he was bright, and, when he went back to Paris, all that material turned into gold."

Gold it was and gold it remains. As Charlie Hebdo's Jean-Marc Reiser wrote of Goscinny's passing, "Now he is dead… But he was always ahead of us."

• Goscinny Beyond the Laughter runs at the Paris Museum of Jewish Art and History until 4 March 2018; Goscinny and the Cinema runs until the same date at the Cinemathèque Français. The show's catalogue, René Goscinny Au-Dela du rire (Hazan), is excellent; a wonderful work of record

• Pilote La Revolution BD by Aeschimann and Nicoby is available through Dargaud.

————————————————————————————————————

- Le Roman de Renart

- Uderzo se raconte, Albert Uderzo (Stock 2008), Goscinny et moi, José-Louis Bocquet (Flammarion, 2007)

- José-Louis Bocquet, Goscinny et moi: Temoignages (Flammarion, 2007)

- Jean "Moebius" Giraud died in 2012; the book relies on Aeschimann's interviews from 2009. Marcel Gottlieb (Gotlib) passed away a year after the book was published.

- José-Louis Boucquet, Goscinny et moi: Temoinages (Flammarion, 2007)

- Back in 1970, when their employer Hara-Kiri was suspended for second time, it had been Goscinny who gave the trio employment. In 1971, Gébé joined a new Hara Kiri Hebdo. It, too, was banned and then reborn as Charlie Hebdo. Cabu and Reisier left Pilote for Charlie.