I.

For some reason, Kim Deitch has long been a cartoonist whose admirers feel that his is a case requiring special pleading. Prior to his remarkable bout of publishing in the last decade—which finally saw the collection of his masterworks Boulevard of Broken Dreams and Shadowland, as well as assured work elsewhere—Art Spiegelman referred to him as “the best-kept secret in the avant-comix world,” a cartoonist “with only a cult following to support him,” while Jim Woodring characterized him as “an artist's artist,” dedicated single-mindedly to his craft, appreciated most by “a solid core group of admirers who recognize that he is one of the best cartoonists who ever lived.” Even after the flood of Deitchiana that commenced with 2002's Boulevard, the line on the man's work is that it remains ever underrated, perpetually ripe for rediscovery. His books often arrive loaded with forewords, afterwords, appendices, galleries, sketch work, photos—as though the work itself were insufficient, as though it yet required documentation, supplement, something more to grab us by the collar and demand, “look!”

But why do such attitudes and textual apparatus so often seem to orbit the world that Deitch creates? In mulling over this question, I don't mean to suggest that the work warrants anything less than the most hyperbolic boosterism—it does—or to imply that the added material is ever anything less than a very welcome bonus. Of course the color work we pore over in the back of Shadowland is subtle and vibrantly mellow, deserving of its own showcase; elsewhere, Deitch's preparatory sketches of Waldo and others, filled with idiosyncratic figure study and notes of self-admonishment, grant insights into both character and creator. And the artist's accounts of his projects' real-world beginnings are as loopy and intricate as anything in the stories themselves, replete with tales of death-row correspondence with John Wayne Gacy, or encounters with enclaves of robustly healthy 90-something Angelenos. All this effort that goes into explaining, illuminating, and commenting upon the universe in Kim Deitch's mind is really just the logical extension of the explaining, illuminating, and commenting that goes on in that world itself; in fact, all this elaborate outgrowth, for Deitch, is integral.

And if it overwhelms us, as readers, it appears to have the same effect on its maker. More and more, Deitch’s stories depict the artist himself, eyes agog at the information imparted by all the emails, news clippings, television programs, stoned anecdotes, eBay winnings, and other such stuff of dreams that contribute to whatever saga he's lately determined to set down. Add to this that Deitch’s growing bibliography constantly loops back on itself, reviving old characters, tweaking old plot points, and you have a body of material endlessly ready to be set up in new configurations, the author always eager to lead us back through one arcane connection or another. So it is that we discover the link between Waldo and Judas Iscariot, or the “real” fate of Fowlton Means, a character based on a pseudonym Deitch discarded decades ago. As Bill Kartalopoulos notes in his essential Deitchian primer, which opens last year's The Search for Smilin' Ed, each new fact that Deitch introduces to a story not only adds another facet to that particular narrative, but also serves as an addition to the grand narrative, demanding revision, reinterpretation, and reconsideration of everything that's come before—just like the addenda and encomia that surround his finished work.

II.

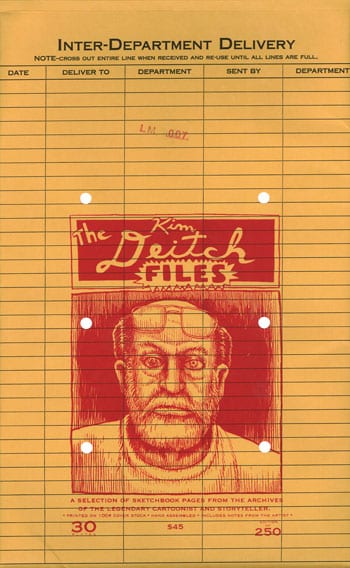

The Kim Deitch Files is the latest entry in this tradition of explaining and illuminating the cartoonist's universe. Here, cartoonist and publisher Zak Sally culls 30 compositions from Deitch's sketchbooks, and reproduces their shimmering but solid pencilwork on weighty paper stock. The plates range from the truly sketchy—studies of cats, of poses—to attempts at page breakdowns and panel progressions, to seemingly finished work—the images intended for Kramers Ergot 7's faux soda ad, for instance, have altered very little from conception to execution. Despite this polished appearance, as Sally remarks in his notes accompanying the package, each sketchbook excerpt is but a “first draft” in what Deitch calls an “intricate system” of preparation and refinement. So, for as much as the Deitch Files stands on its own, as testament to the cartoonist's almost architecturally sturdy designs, it too cannot help but point back to the completed work, demanding we revisit and reconsider it.

The Kim Deitch Files is the latest entry in this tradition of explaining and illuminating the cartoonist's universe. Here, cartoonist and publisher Zak Sally culls 30 compositions from Deitch's sketchbooks, and reproduces their shimmering but solid pencilwork on weighty paper stock. The plates range from the truly sketchy—studies of cats, of poses—to attempts at page breakdowns and panel progressions, to seemingly finished work—the images intended for Kramers Ergot 7's faux soda ad, for instance, have altered very little from conception to execution. Despite this polished appearance, as Sally remarks in his notes accompanying the package, each sketchbook excerpt is but a “first draft” in what Deitch calls an “intricate system” of preparation and refinement. So, for as much as the Deitch Files stands on its own, as testament to the cartoonist's almost architecturally sturdy designs, it too cannot help but point back to the completed work, demanding we revisit and reconsider it.

Though the collection samples subject matter from the past couple decades of Deitch's production—from his Nickelodeon kids' serial Southern Fried Fugitives, to unpublished illustrations for a Lewis Carroll adaptation, right up through his proper books all the way to Pictorama—there is no one story here complete and entire, no truly finished work. Nor, if we are reading this as a “complete” Deitch work in itself, would we expect there to be. As with the rest of Deitch's finished work, the story being told in these roughs is one of process, of investigation, of tenuous links being sussed out and becoming solidified. Reading The Kim Deitch Files, as opposed to paging or glancing through it, results in every bit as much a detective story, a delving into the disjointed past, as any entry in the Deitch canon from Hollywoodland to The Search for Smilin' Ed.

And what a search: as one of the preparatory drawings for The Stuff of Dreams says here, “one discovery leads to another! But where will it end?” This is always Deitch's way, in his tales of private eyes, newshounds, amateur internet sleuths, and rabid collectors: ferret out the lead, track down the raconteur, find the lost film or the corpse or the missing matinee idol, and just you see if that doesn't put you on the trail of even greater mysteries, buster. Deitch's characters must look as hard as they can into what's in front of them in order to make sense of their world, whether it's a gold tooth poking out of the sidewalk in Shadowland or a hollowed-out frog doll in Ed. What the plates in this portfolio help us realize, as readers, is just how much Deitch encourages us do the exact same thing with his cartooning. Look!

III.

Many of the images here, in comparison with their later revisions as published in book form, are only half-realized, incipient. Packed as they are with verbiage and detail and implication, when Deitch revisits these roughs for their more fully cartooned reworking, he must untangle their webs of information, expanding upon them for panels or pages at a time.

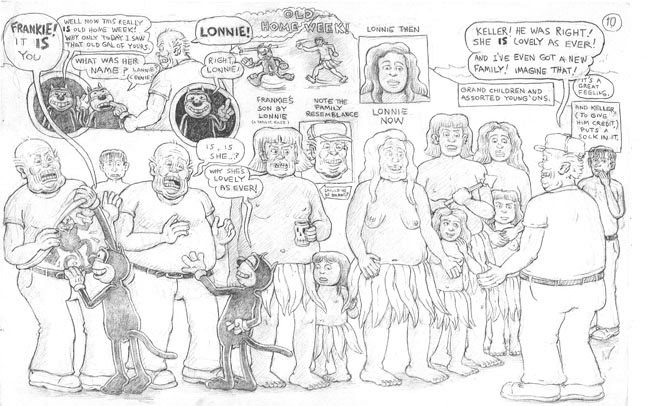

One plate, here, which shows Waldo bringing about the reunion of an old sea-faring friend and his long-lost island-dwelling love, is positively thick. The page deals in tortuous family history, the past adventures of Waldo and his acquaintances, and a narratorial voice that comments on the image, interpreting the goings-on. It is, in its unassuming way, as complex as those diagrams in Jimmy Corrigan which pull apart the tight-knit knots of family and history. Unlike Ware, though, when Deitch finesses this draft in the first issue of The Stuff of Dreams, he unpacks the information sardined into this initial image over the course of not one, but six pages—adding a flourish here, clarifying a lineage there, and generally just stretching rangily out.

On closer look, all of the images collected here are just as dense with significance, and require us to read just as attentively. After all, if Deitch himself needs to translate these images from “draft” to final story, from oblong legal-paper format to upright comics page, and from singular moment to narrative sequence, it should come as no surprise that we must linger over these compositions too. It is almost as though Deitch presents himself with the challenge of using one image to explore as much incident and backstory as he can.

So, in a portrait of neglected black sheep Nate Mishkin passed out drunk, Deitch lards in enough detail to encapsulate both the entire career of his Winsor McCay stand-in Winsor Newton, and the involved family saga of the Mishkins. On another page, the story of Christ's crucifixion, the history of bottle cap art, the legacy of big band jazz, the interactions of underground comic art and psychedelics, and the final resting place of an aged cancer patient, all swirl together and comment on each other in a clear but complex array. Deitch's images, like his books, somehow bear all the burden of history without collapsing under such heft.

So, in a portrait of neglected black sheep Nate Mishkin passed out drunk, Deitch lards in enough detail to encapsulate both the entire career of his Winsor McCay stand-in Winsor Newton, and the involved family saga of the Mishkins. On another page, the story of Christ's crucifixion, the history of bottle cap art, the legacy of big band jazz, the interactions of underground comic art and psychedelics, and the final resting place of an aged cancer patient, all swirl together and comment on each other in a clear but complex array. Deitch's images, like his books, somehow bear all the burden of history without collapsing under such heft.

Throughout, Deitch is also fleshing out his idiosyncratic curation of 20th century pop culture, discerning connections between seemingly disparate subcultures that would otherwise remain happily insular obsessions: What line, he wonders, can we draw between turn-of-the-century temperance lectures and prohibition-era stag films? Deitch somehow allies the two in Smilin' Ed. Just how does the underground press fit in with the history of bottle-cap art? See Pictorama for an explanation. Or, in Alias the Cat, how deep do we have to dig to connect the world of the Furries with that of silent adventure serials? In answering such questions point by point, each new chapter in Deitch's work functions as a footnote to the rest. At the same time that they rollick along as captivating capers, as tales whose tallness we're only too happy to believe in, Deitch's comics also slyly function as a kind of irrepressible annotation, as margin-writing expanded to novel length, midrashic attempts to understand and explicate the undercurrents of the American century.

IV.

In the La Mano portfolio, these tantalizing glimpses of Deitch's tales (and our pop histories) are like overloaded snapshots of the storylines roiling in his mind at any one time. They resemble nothing so much as lobby cards for old movies, artifacts that wouldn't be out of place in the decaying entrance to some abandoned cinema in one of Deitch's elegies for the films of yesteryear, or buried in stacks of paper goods found in the estate auctions of his departed kooks. Like those sensational, captivating lobby cards of yore, Deitch's sketchbook compositions freeze moments in time and lengthen their narrative significance, excerpt a story in medias res and promise similar clusters of furious activity stretching back before the moment we see, and well on into the future. Like so much of his finished work, these drafts are at once reflective, propulsive, and resolutely still, pointing off in all directions at once while they remain entirely self-sufficient.

Drumming up installments in his Southern Fried Fugitives series, Deitch communicates the most of this kind of marquee mystique. In these images, intrepid kids evade drunken geeks in exotic locales as they fight for animal liberation, or they face fiery death in a mad scientist's lab while monsters swoop in and shadowy figures lurk in the background—you can almost smell the butter and popcorn. But other plates, like the one where decrepit animation studio maven Fred Fontaine holds forth on his vision of a Waldo-themed amusement park, or where the denizens of Wonderland array themselves in parade ranks around Alice, or where the hectic floor of a bottle-cap convention sprawls and boils over, are pure spectacle. Here Deitch asks us not to wonder at the intrigues his stories might possibly detail, when he actually gets to the point of unraveling them. Rather, the showman demands that we simply revel in all this termite-like activity, in all the display of scenery and of stuff that he has collected and would conjure up for us.

V.

For as much as it has become commonplace to think of Deitch as a yarn spinner first and foremost, as a “writer who draws” or a storyteller, he remains every bit as dedicated to the delights of the spectacular. Not that the two are anything other than intertwined—Deitch's most showstopping moments, from Boulevard's madhouse daydream, to Ed's party in celebration of Waldo, are at once grand circuses of activity, and vast summaries of the stories that precede them. In Shadowland and Ed, especially, where we learn that in Deitch's cosmos an alien race records and preserves every aspect of human creativity they can witness, storytelling becomes inseparable from spectacle.

For Deitch, every human story is worth watching and understanding, no matter how marginal or inconsequential, just like every display of human activity is worth dilating out into its own story. In the artist's world, devoting one's entire existence to unearthing these stories, and granting them some kind of showcase, becomes laudatory in the extreme, and redeems everyone from drunken huckster Doc Ledicker to a pack of demons from hell, all the ne'er-do-wells and miscreants who find themselves aimless in Deitch's modern world. To watch, to organize, to preserve, in whatever way one can—these are the values of Kim Deitch's universe, and they are values revisited and clarified in The Kim Deitch Files. These drawings demand that we pay attention, that we try to decipher, that we revel in detail and incident—and in doing so, they remind us that these are the redemptive pleasures that Kim Deitch holds out, benevolently, and with enthusiasm, to his characters and readers alike.