If his autobiographical reminisces are true, then Hayashi Seiichi’s literary life began with falling tears. As he recalled the early 50s in “Azami Light” (“Keikō,” 1972): “‘Look at you sniveling like a little girl,’ said my mother. She turned her back on me and got into bed. The book I was reading was so sad that tears kept me from falling asleep. A girl I just met had lent me A Dog of Flanders. For two or three days it made me cry before going to bed. This was the first book I read. I was in first grade.”

When it comes to male cartoonists in Japan, one usually thinks of mystery, action, and adventure as their starting point. But until the mid sixties it was not uncommon for those early in their careers to draw tear-drenched or comical tomboy shōjo manga side by side with science fiction and youth detective tales. Ishinomori Shōtarō and Akatsuka Fujio drew numerous such comics in the 50s and early 60s, as of course did their mentor Tezuka Osamu. Ushio Sōji and Higashiura Mitsuo, two of Hayashi’s childhood favorites, split their time between shōjo material and historical jidaigeki, the latter executed with a softness and sentimentality that expresses the bleeding of shōjo aesthetics into the shōnen bastion of ninja and samurai Edo. Shirato Sanpei, famed as an author of violent ninja and peasant rebellion stories for young men, created his first overtly socially-engaged works in the late 50s as shōjo manga. Especially within rental kashihon, comics for girls were dominated by stories about war orphans, terminal childhood sickness, family poverty, working kids, and class discrimination. While interiority, fractured picture planes, and the bending of gender norms are often foregrounded as shōjo manga’s central contributions, the obsession with melodrama also gave girls’ comics the lead in exploring social problems and personal tragedy.

One finds an entirely different way of exploiting female tears, and an entirely different kind of gender-crossing, in Hayashi’s work of the late 60s. The work cannot be classified as shōjo manga, published as it was in the male-dominated and male-targeted Garo, and treating as it does women’s emotions and experiences, not young girls’. Furthermore, while heartbreak and depression and crying recur, one cannot exactly describe his stories in the terms of psychological depth and intensity used in manga for female teens and young women especially after the emergence of the Shōwa 24 Group in the early 70s. Emotion is strong in Hayashi’s work, but it is almost always expressed, and self-consciously so, through popular culture clichés, whether they stem from woodblock prints, folktales, children’s literature, film, or music. In the case of “Flowering Harbour” (“Hanasaku minato”) -- the focus of this essay -- first published in the May 1969 issue of Garo, the primary such medium is enka, a genre of music that is sometimes referred to in English as Japan’s “country music,” sometimes as “Japanese blues.” There are numerous rock and roll manga from the late 60s and early 70s, and later decades would bring manga about enka stars, real and fictional. But Hayashi appears to have been the first and one of the very few to try and embody the aesthetics of the music in comics form. In the 70s and 80s, he also designed not a few enka record covers.

What is enka? The genre is rooted in traditional-styled recorded popular music (kayōkyoku) from the 1930s. Its rise after the war is associated primarily with singer and movie star Misora Hibari, who began during the Occupation as a child performer of boogie-woogie numbers. By the mid-late 50s she had worked traditional festival and folk music into her songs, and by the mid 60s was singing in the lachrymose style that came to define enka. In the years following, enka emerged as a distinct genre within the Japanese music industry, though until the 70s the broader name kayōkyoku was typically used.

In his book on postwar popular music, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon (2012), Michael Bourdaghs enumerates the characteristic features of enka as follows: “it is sung in a minor key, its melody follows a pentatonic scale, and its ornamentation is provided by Western instruments masquerading as Japanese counterparts.” The singing often employs “vibrato and melisma (shifting between multiple tones on a single syllable).” Stage costumes are generally extravagant. Kimonos and Western-style formal wear are equally common. “Song lyrics tend toward an exaggerated nostalgic sorrow, and tearful spoken passages . . . are common.” In her study of enka, Christine Yano looks at what she calls enka’s public imaginary of a “communally broken heart,” in which tears become the medium for an odd type of Japanese exceptionalism based on a special national ability and fondness for crying.

As for the lyrics and performances, highlighted in recent scholarship are those songs and singers nostalgically fixated on lost roots: rural hometown, country roads, country scenery, festivals, and mothers. Male urban immigrants thus often enjoy pride of place in understandings of enka, especially sociological ones. However, in the mid-late 60s most of the new hits were set either in Tokyo or regional cities and harbour towns, in bars and on waterfronts, and typically starred rambling men and abandoned women who expressed little feeling for family or the countryside. The main shared sorrow was adult romantic heartbreak, not cultural homesickness.

Many of these “Japanese blues” numbers were actually covers of songs written in the 1930s, indicating that enka’s melancholy derived from middle-class urban alienation in the early Shōwa years. Similarly, while the influence of traditional Japanese classical and folk music is strong in some kayō forms, musical structure and instrumentation borrowed heavily over the years from American blues, jazz, Spanish guitar, mambo, and chanson, amongst other world music genres. Especially important was the “yellow music” of continental Asian jazz. Many of enka’s original writers and performers cut their teeth in Korea and Chinese metropoles like Shanghai in the years when the Japanese Empire held sway.

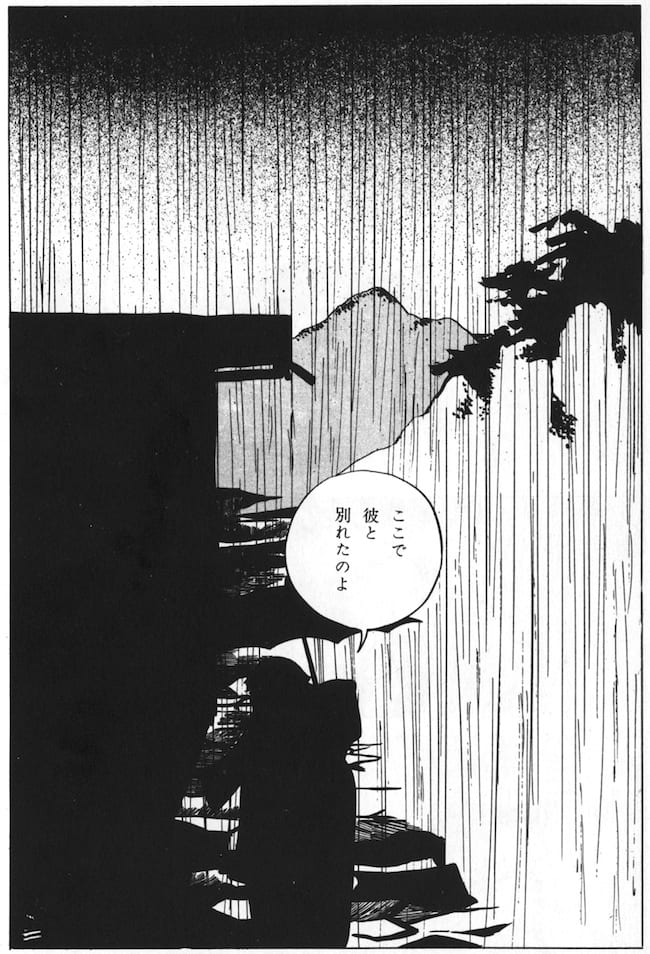

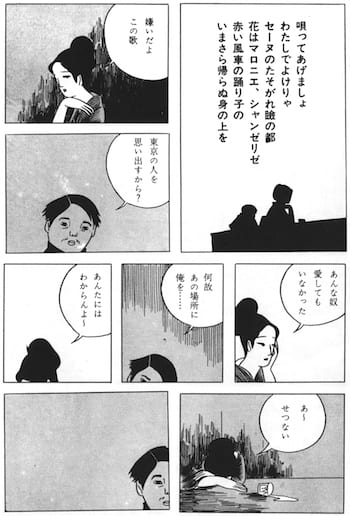

In 1969, no Japanese reader of “Flowering Harbour” would have missed its enka-esque imagery. The story depicts the ephemeral and unconsummated romance between a single mother, proprietor of a small bar in some lonely harbour town, and a man travelling through from Tokyo. He drinks himself to near collapse in her store. Seeing that he has no money for an inn, she invites him to spend the night in her room. They find her daughter, a cute girl of maybe five or six, having cried herself to sleep in the corner. The next night the man and woman drink together, the lyrics of famous kayōkyoku (discussed below) floating in to wrap their sorrows in popular song. She wallows in having been abandoned by a “lovely man” from Tokyo some years ago. The cause of his depression is never described, though he is desperate enough to contemplate throwing himself into the storm-whipped waters. She holds him back. Eventually they part. She wants the moment to be romantic, so asks him to hold a paper streamer as he fades away into the storm.

In “Bohemian Living,” the new afterword Hayashi wrote for the English edition of “Flowering Harbour” from Breakdown Press, the artist provides as background the mass migration from periphery to Tokyo that fueled Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1950s and 60s. It would be worth considering how “Flowering Harbour” compares with other Garo-related artists dealing with similar subject matter at this time, like Tsuge Yoshiharu, Tsuge Tadao, and Tatsumi Yoshihiro. If those artists focus primarily on the experiences and fantasies of men, however, Hayashi foregrounds that of a woman.

The representation, however, is self-consciously clichéd. While the motif of the single mother is, to my knowledge, not something one finds enka, the lonely stormy harbour, the pining female bartender, and the wandering man refusing all attachments are the very stereotypes of that musical genre, as is the final parting scene on the jetty. Hayashi mixes these motifs with others to link the sentimentality of enka with that in other cultural fields. In his titles, Hayashi often refers to blossoming flowers and falling petals, Japanese culture’s most famous symbols of transience and vanity. Flowers, like struggling mothers, were also an important part of 50s shōjo manga, which Hayashi also read occasionally as a boy.

In the 1970s, some critics began referring to Hayashi as the “Yumeji of the Postwar Period,” in reference to Takehisa Yumeji (1884-1934), whose wispy jōjoga (lyrical pictures) came to define shōjo illustration in the 1920s. The full-page image on page 3 of the manga is strongly reminiscent of Yumeji’s work, with its flat patterned quality, linear contours, and effusive melancholy. The way it freezes the narrative for a page to accentuate melodramatic feeling also recalls the adaptation of prewar jōjoga within the so-called “style pictures” (sutairu-ga) of postwar shōjo manga.

Yet instead of the European fantasies that usually frame these elements in shōjo manga, Hayashi opts for a Japanese-y look that accords better with the imagery of enka. The fading tone across the top of some page-wide panels has been borrowed from Hiroshige’s raining landscapes from the nineteenth century. Some people associate enka’s obsession with romantic longing with the melancholy of Japanese poetry; Hayashi’s shigajiku (poem-painting)-like coupling of lyrics and image leans in that direction. Calligraphic titles are common on enka record covers. Those for Hayashi’s title pages were written by his mother.

Later it will be argued that this highly conventional (and very enka-esque) mother-nation-tradition chain of signifiers has been articulated within a self-consciously male style of comics making (a move which is also enka-esque). First let’s dive into the details of Hayashi’s musical references. In “Flowering Harbour,” he cites three songs, and it is with them that the work’s relationship with popular music becomes personal, and sensitive to the hybrid cultural and geopolitical history of enka beneath the standard clichés – though legible as such only if you know a bit about Hayashi and the songs. It is important to remember while reading the manga that these songs were all famous, and many contemporary Japanese readers would have recognized them simply from Hayashi’s brief quotations. Therefore, graphically mute as these text blocks might be (unlike the calligraphy of the title page, they are distinguished in the original only by bold font), they would have nonetheless incited a reader’s auditory imagination. Amidst the panels they could have heard, and perhaps they would have hummed, specific melodies and specific vocal stylizations.

Two of the songs are from the 1950s, and sharply reflect the experiences of the immediate postwar period. The first Hayashi cites is Tsumura Ken’s “Lil Back From Shanghai” (“Shanhai gaeri no riru,” 1951), written by Tōjō Juzaburō and composed by Tokuchi Masanobu. Its most famous refrain hangs over Hayashi’s female bartender as she drinks herself to tears.

Watching the boats

From the harbour cabaret

The winds rumored of my Lil

Lil, Lil coming home from Shanghai

To a mid-tempo tango backing, “Lil Back From Shanghai” is sung from the viewpoint of a man who has recently been repatriated from the continent. He is in search of a woman from whom he was separated one foggy night on Shanghai’s Fuzhou Street, located in the city’s bubbly foreign concessions. He imagines her now lonely, watching the boats while working in some Japanese harbour cabaret. (Some fellow's skilled karaoke version of the song is here).

He calls her “Riru,” a mildly Chinese-sounding name that is the Japanese pronunciation of Lil, as in composer Harry Warren and writer Al Dubin’s “Shanghai Lil,” the climatic number in Busby Berkeley’s musical Footlight Parade (1933). “I’ve been looking high and I’ve been looking low,” sings James Cagney playing an American sailor, fallen for an opium den seductress. “The little devil was just a butterfly, but you discover something on the level, shining in her eyes. Oh I’ve been trying to forget her, but what’s the use I never will.” Eventually he finds her hiding in a chest. “I miss you very much a long time,” she says in her darling Chinglish. They exchange verbal affections, then tap dance. She wants to escape Shanghai with him on his ship, which she does masquerading as a sailor.

“Shanghai Lil” was well known in Japan. No less than twelve Japanese versions were recorded between 1934 and 1939. In 1936, the song was also included in one of the Busby Berkeley-inspired follies in the Takarazuka Revue. Tsumura’s “Lil Back From Shanghai” is essentially a sad après guerre sequel to the ebullient show biz glitz of the pre-1945 original. The idea for the song came to a producer at Tokyo’s King Records while listening to “Missing Persons” (“Tazunebito”), a radio program begun in 1946 to help people find their loved ones amidst the shambles of defeat. “I thought,” recalled the producer many years later, “wouldn’t it be interesting to slap ‘Missing Persons’ and ‘Shanghai Lil’ together?” The first few notes of the intro cite Warren’s music before shifting into its own slower, mellower, more typically kayō phrasing. Tsumura is also looking high and low for his Shanghai Lil, but now the cause of separation is decolonization in China and forced repatriation to Japan, versus the racy fast life of the Whore of the Orient as depicted in Footlight Parade.

The song struck a major chord. It sold almost 300,000 copies in its first two years. Tsumura soon recorded a series of sequels to this sequel. A novel, then a movie, and then another movie were quickly made, indicating not just the catchiness of Tsumura’s original tune, but also how widely the lyrics resonated in post-Imperial and recently war-devastated Japan. People showed up at Tsumura’s door claiming to be or to know the girl he had been looking for. One letter informed him that Lil was well but he should be careful because her new beau was a dangerous thug. A bevy of hostesses and dancers newly named Lil suddenly graced Ginza bars and cabarets. Meanwhile, little Seiichi, a repatriate from China himself, heard the original 1951 song many times as the new theme of “Missing Persons,” which continued on the radio until 1962. Hayashi also recalls the song playing at the close of a serial radio drama in the early 50s.

The second song that Hayashi cites in “Flowering Harbour” is “Casbah Woman” (“Kasuba no onna,” 1955). It is again about a bar lady, this time in Algeria. She also has been left behind by a lover, a member of the French Foreign Legion.

If you wish I’ll sing you a song

Dusky eyed city of the Seine

Flowers of the horse chestnuts along the Champs-Élysées

And the dancer with the red pinwheel

Who can now never go home

“I hate this song,” says Hayashi’s single mother, painfully conscious that her life mirrors popular stereotypes of the defeated woman. With her comment, the reader suddenly realizes that the floating text is actually sound from a radio or a record player, tuning one’s ears to the manga’s on-again off-again aural dimension. “Casbah Woman” too dates from the 50s, and while its lyrics do not directly reflect the war, they build on the sentiments that “Lil Back From Shanghai” had capitalized upon.

As the story of the song’s making goes, songwriter Kugayama Akira, a Japanese Korean, had come up with something in the vein of 30s kayō blues with a touch of “Johnny Guitar.” Ōtaka Hisao, a popular lyricist, found it too like earlier kayō songs for the lyrics to be set in Japan, so he pulled a new setting out of his memory: the romantic Casbah of Jean Gabin’s Pépé le Moko (1937). What you hear in the Japanese song are the echoes of Pépé’s romance with the luxurious Parisienne Gaby Gould. I imagine the fact that Algiers was a colonial city, as Shanghai had been, was also part of the sell. The song was recorded by the deep-voiced Eto Kunieda, and was intended as the title track for a movie named Midnight Woman (Shin’ya onna). The film never materialized and, as a result, Eto’s “Casbah Woman” flopped.

What was the twenty-four-year-old Hayashi doing in 1969 mining tunes from a distant decade ago, mucking about in the experiences and sticky sentiments of his mother’s generation?

(cont'd)