From The Comics Journal #42 (October 1978)

Claire Bretécher is currently the most popular (and very probably the best) cartoonist working in France. The two books she has edited and published herself, Les Frustrés and Les Frustrés 2, consisting of material culled from the regular strip she does for the weekly French news magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, are among the wittiest, sharpest, and most insightful collections of contemporary satire appearing in any medium. Hence, it is indeed a cause for celebration that the National Lampoon has undertaken to bring us translations of her strips, both in its monthly pages and in a luxurious softbound book called The National Lampoon Presents Claire Bretécher. The strips appearing in the Lampoon are translations of “Salades de Saison,” a series of Frustrés-type pages done for the satirical weekly Pilote several years ago (back when it was a weekly, in fact), while the book reprints approximately two thirds of the first two Frustrés volumes. Between this and Bretécher’s appearances in Ms., America is being submitted to a veritable barrage of Bretécher, and it is probably the most palatable gallic import since champagne.

Although Bretécher is on weekly display in an avowedly political (leftist) magazine in France, and although her rumpled, big-nosed, and slightly androgynous characters spend much time discussing matters political, it would be wholly false to construe her to be a political satirist. As a matter of fact, she has frequently asserted that politics bore her. Rather, as a social satirist, she examines the effect of life upon people—and politics, like pseudo- and anti-intellectualism Freud, mothers-in-law, and contact lenses, is just one more thing the human animal has to cope with on a daily basis.

Claire Bretécher’s stance is solidly individualistic. She pokes more fun at the left-wingers than at the conservatives, but this is presumably because the latter have been so thoroughly discredited in French circles that it would be tantamount to flogging a dead elephant to take them on. Besides which she, like most anyone else over there, probably navigates mostly in liberal waters and thus finds more first-hand material there to laugh at. Similarly, feminists catch a lot of flak from her, but more for their inanities and superficialities than for any deep ideological disagreements she might have with them.

Few of her strips are actually gag strips, reaching a climax in a liberating explosion of laughter. The laughter is cumulative; it builds as we realize that the crescendo of insanity we are laughing at is our own, and that of our closest friends. This is not to say that her strips are merely rambling “slices of life” a la Robert Crumb; indeed, every strip is constructed as tightly as clockwork, every phrase and gesture contributes to the theme of the strip, subtly leading the reader to the conclusion with no trivial stops along the way. In other words, the events are pared down to their basics with strict discipline, but not straitjacketed into a vulgar gag.

Although she has been compared to Garry Trudeau—and it is, in a sense, a fair analogy—her drawing and his are at opposite poles. His is carefully rendered and graceless (Trudeau is by no stretch of the imagination an artist), hers expressionistic and vivid. It is partly inspired by such American cartoonists as Johnny Hart and Brant Parker, whose work she admires greatly, and displays the same appealing mixture of superficial looseness in rendering and tightly controlled effectiveness. They all know precisely which elements in the panel can be dismissed with an offhanded doodle (who the hell cares about feet?), and which must be delineated with precision, however stylized. Bretécher’s bizarre faces can convey any feeling or any mixture of feelings, and her expertise at using a minimum of background to situate the strips perfectly is evident throughout the book.

In general, the American edition is excellent. The reproduction is as good as in the original, the translation for the most part right on target and fluid, and various aspects of the production (such as the remarkably authentic emulation of Bretécher’s scrawl in the non-captions and the titles by Heavy Metal’s art director, John Workman) are flawless. It should thus be made clear from the outset that at $5.95, The National Lampoon Presents Claire Bretécher is the single best comics buy of the year, and that each of the 80-plus strips therein contains more chuckles than an average month’s worth of Sunday comics sections from any major American newspaper. It comes heartily recommended with the sole reservation that if you can read French, the original versions are of course better.

Translation is a difficult craft (or art). If the translator is less than fluent in the language of origin but fully conversant with the target language, the result is frequently a grammatically, idiomatically, and dialectically “correct” translation, but unfaithful to the original and in some cases downright nonsensical. On the other hand, if it is the target language that is the weaker of the two, awkward and ruptured translations abound. Upon buying the book and noticing the name of the translator, Valerie Marchant, I expressed some concern that it might be one of Bretécher’s cronies with an M.A. in English and that the book would boast a conflagration of massacred pseudo-colloquial English with gallicisms running rampant. (“I demand pardon of you.” “Oh, that makes nothing,” for instance.) Happily, I found this not to be so, and with a few awkward exceptions, particularly when coping with the labored ironic politeness that is the staple of French argument (“Quit it with this shit, please.”—“Mood Music”), the English dialog flows nearly as well as the original. Sadly, several strips are rendered pointless or even unintelligible because Ms. Marchant’s command of French was shaky enough for her to misunderstand the originals. A few examples will suffice.

In “Kathy,” a racist remark (“Don’t play with the little Arabs” in the original) is diluted into “little ruffians,” which does not sabotage the strip, but weakens it. In “A Life in the Theatre,” a casual dismissal of an actor (“He never understood theatre, it’s that simple.”) is transmogrified into a convoluted “Hoffman? He never learned that theatre isn’t a mental exercise,” which stops the reader short and confuses him at the wrong point of the strip. In “Ruminations,” a character claims that we must “re-invent a new way of living,” to which a semantically conscientious witness responds “a redundancy, honey”; Ms. Marchant drops the guilty prefix “re-,” thus rendering the response incomprehensible.

While the above strips are merely weakened by the mistranslations, others suffer a more dismal fate.

In “Cellulite,” two women spend 10 panels bemoaning the state of their bodies; in the 11th, one says, in essence, “The hell with this—I’m not out to please men by looking sexy.” The 12th, and last panel shows the two women glaring at each other, fully aware that that is precisely what they are out to do. Ms. Marchant reverses the penultimate panel so that it reads, “God, the whole idea of my body drives me crazy,” which ruins the irony and is awkward besides. In “The Creative Woman,” a “fabulously successful folk singer and creator of raiku pottery” verbally flagellates herself on a talk show for having been aided in her career by “class privileges,” and finally asks the talk show host to “please kick my ass” as penance. In English, it becomes the insulting “would you please kiss my ass”! Neither of these strips makes much sense in the translated version.

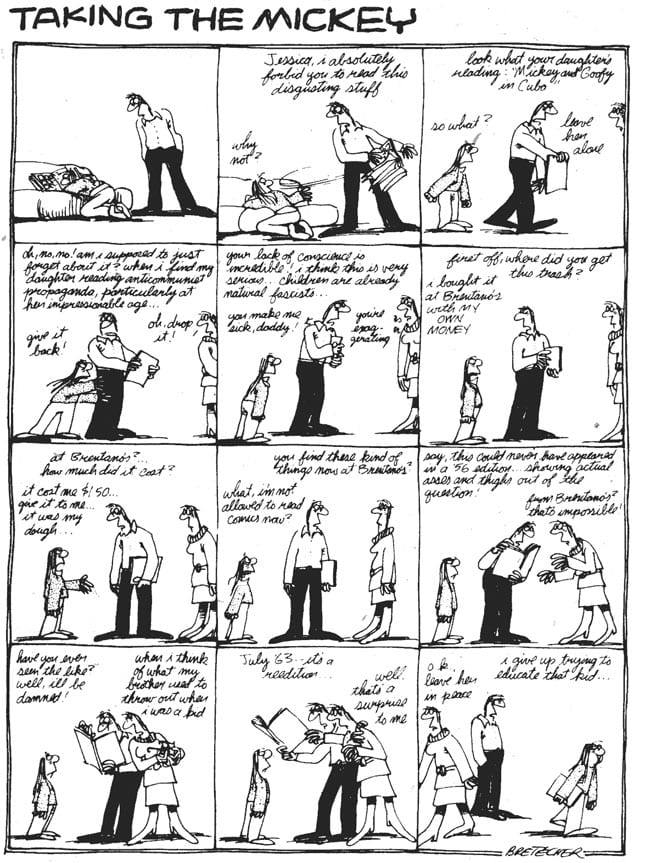

By far the most idiotic translation, however, occurs in “Taking the Mickey.” It reads originally like so: a Marxist father becomes indignant at seeing his daughter reading a copy of Tintin au Pays des Soviets, the first Tintin book, which is notorious for three things: the utter crudity of its execution, the high prices it demands as a collectors’ item, and the low, vicious anti-Communism that permeates it. The father becomes sidetracked from his indignation over its third characteristic when he remembers its second one in mid-tirade. “This book,” he muses, with a charming French idiom, “costs the skin off your ass” (“an arm and a leg,” in slightly more prudish anglo-saxon). When he discovers that it is nothing but a reprint, his capitalistic greed is stopped in mid-flight, and everyone more or less returns to his own business. A funny and effective strip. By the time Ms. Marchant gets through with it, it is positively side-splitting—for those who enjoy bloopers.

She first adapts Tintin au Pays des Soviets to “Mickey in Cuba,” a to my knowledge apocryphal Disney title, but fair enough in view of the Studios’ habitual political stance. (Remember the worthless “Castrovian Rubleniks” Uncle Scrooge pacified his pecuniavorpus goat with?) But the crucial ninth panel comes out as, “This could never have appeared in a ’56 edition — showing asses and thighs out of the question,”!! (Even allowing for colloquial speech, aren’t syntax and punctuation off here as well?) Not only does Ms. Marchant forget what she is doing from one panel to the next, she also misreads a simple French expression so badly it casts doubt upon her proficiency in French being on even the M.A. level. In translation, it is the idioms that best reveal idiocy on the part of the translators.

A final minor point, but also indicative of less than knowledgeable editing, is the use of the spot illustrations that punctuate the book, breaking the monotony of the page-long strips. (The book is a bit hefty and can grow wearisome even for Bretécher fans if they try to read it in one sitting; the French ones were 20 pages shorter, an ideal length.) In the original, these spots served as intros or codas to strips with the same theme—for instance, the sunbathing woman accusing the blind man of being a “voyeur” appeared directly, after “Sun Worshipers”—giving them an added twist. Here, they are just scattered throughout the book like so much parsley, in addition to being printed much too large. It is obvious that Bretécher did not have final approval over the book, or she would certainly have corrected this.

Still, blundering translations and all, this remains a hilarious book. If you thought Asterix was the epitome of French comics art, take a dose of Claire Bretécher. But be careful when sampling—you may fall in love. I did.