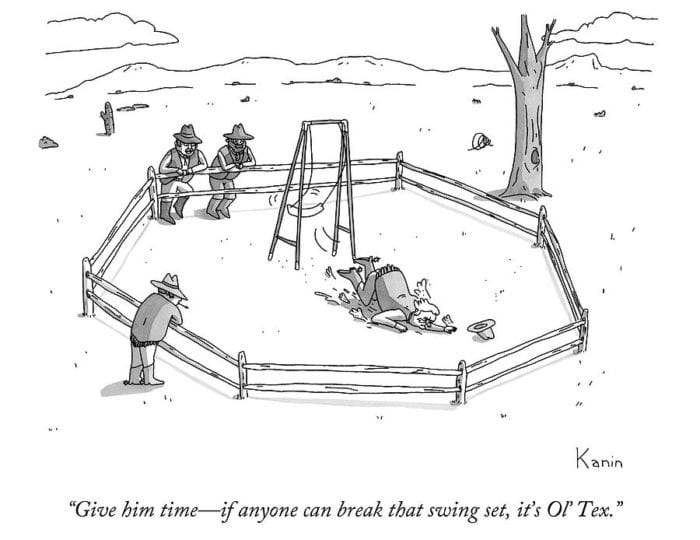

For more than a decade, Zach Kanin has been creating gag comics full of bizarre scenarios and potato-bodied bumblers for the pages of The New Yorker. Throughout that time, Kanin has also written for several television shows, such as Saturday Night Live, and now produces Comedy Central’s Detroiters. We discussed his cartoon submission process, his attempts to be timeless, and why he had to duck flying projectiles at work.

RJ CASEY: I find it somewhat of a pleasant surprise that someone who started by gaining success through cartooning and then branched out to other ambitious projects is still drawing cartoons. That’s rare. It seems like if someone leaves cartooning for a while, you never hear from them again.

ZACHARY KANIN: [Laughs] That’s funny. I love making cartoons. It’s definitely harder to do them now, but I would never stop cartooning.

Do you have to compartmentalize things in your life? You’re cartooning, you’re writing, you’re producing. Is that difficult to pull off at the same time?

It’s not difficult. Well, I guess it can be at times, but I kind of appreciate having all the different outlets. When I was just cartooning, there were times when I would have an idea that was too long for a one-panel cartoon. Single-panel cartoons have to have such a specific type of joke. You have to give a set-up and punch line in just one line and picture. I enjoy having the freedom now to have longer ideas along with the one-off jokes I can do in a cartoon. But when I am cartooning now, I really have to sit down and be like, “I’m doing cartoons.” When that was all I was doing, I would be on the bus or the train and have jokes pop up because that would be my focus.

Sure, that makes sense. Do you consider yourself a cartoonist first and foremost?

I don’t know. It depends on who I’m talking to, I guess. [Laughter] If I’m in a room full of TV writers, I say I’m a cartoonist. If I’m in a room full of cartoonists, I say I’m a TV writer. I don’t know. That’s not really true. I like doing both.

Your title is executive producer now on Detroiters. That’s a title that everyone knows and acknowledges, but I have no idea what an executive producer does. Can you explain that a little bit?

That’s a great question. I also don’t exactly know the answer. It can mean a number of different things. I don’t know the technical ins and outs for everyone, but for me, it means that I’m involved in every aspect of the show. The writing, decision making, casting, picking directors. All the nitty-gritty stuff as well as the creative stuff.

You used to be the assistant cartoon editor at The New Yorker.

That’s right.

What did that job entail?

That mainly was managing the Cartoon Caption Contest, which was fairly new when I started. I think the contest started a year before I got there. I also had to do data entry and stuff like that for the cartoons in the process of getting them through. There were about one thousand original submissions a week for the regular cartoons. About five hundred from the regular stable of New Yorker cartoonists and about another five hundred from the slush pile. I had to go through them and pick which ones to bring to Bob Mankoff, the editor.

Most of my week, though, was going through eight to 14,000 captions for the Cartoon Caption Contest.

[Laughs] Is there a science to that?

Yeah, there are tricks. I put them all on a spreadsheet and would search for things. I would search for “fuck” and “shit” and things that they wouldn’t publish. I could eliminate all those immediately.

OK.

I would also always start out by searching for the word “Geico.” There were always about five hundred submissions that were like, “Good news. Now you’re getting a better deal through Geico.” [Laughter] So many Geico jokes. I was like, “We’re not going to do that!” Searching for swears or for Geico would immediately take about a thousand out of the running for the contest.

Did that job affect your cartooning at all?

The Caption Contest part didn’t. That’s a different kind of beast. That is like having a picture and trying to resolve it with a caption. With cartooning, you are trying to do both parts naturally at once. The caption can be kind of a “hat on a hat” versus cartooning where everything’s on its own. The job itself was great. I got to see not only what people like Jack Ziegler and Roz Chast published, but I got to see nine to fifteen cartoons they weren’t selling every week. It was so cool to see the output of weirder ideas and what certain artists were doing and how they were putting batches together. Bob Mankoff was always very supportive and helpful in guiding me.

What was your relationship with Mankoff like?

It was great. Bob is a real character. He’s really funny and very quick… and very eccentric. He’s always on a kind of different diet. Sometimes he would be on a five-bagel-a-day diet. [Laughter] At one point, he was only eating sweets, I think. He thought that was a good diet. He’s a very thin man, but he tries different nutritional diets or experiments, I guess.

There was one point while I was there where he got obsessed with cards. He went and saw Ricky Jay do a magic show, and Bob was obsessed with the belief that every kid that was born in the Bronx around the time he was could throw a playing card into a watermelon. He thought that that wasn’t that great of a trick. So, for about two months, there would just be playing cards whipping around the entire office. He eventually got one into a watermelon. He bet David Remnick, the editor, that he could do this. I think he won.

It was pretty scary though. I would be sitting there, judging captions, and cards would go whipping by my head fast enough to split a watermelon. It was a little hectic for a while. Bob was great, though.

What do you think Emma Allen is going to bring to the position? Are there many differences since she took over?

She has been great so far. I think she’s continuing Bob’s mission of finding new, young people. She’s looking for younger, diverse voices. It’s very encouraging. She seems pretty hands-on. I love what she’s done with the “Daily Shouts” and the stuff on the website. She clearly has a great sense of humor.

It seems to me that there’s been some sort of editorial mandate over the last couple years to include more popular culture references or punch lines involving the political topic of the day in New Yorker cartoons.

I don’t know. It seems like there’s always been a portion of them that are commenting on current politics. There’re different cartoonists who specialize in different humor. Artists like David Sipress or Paul Noth do both kinds. They do cartoons that are just a weird slice-of-life and they also do political things. But I don’t know about your theory. Maybe they’re leaning more heavily on that, but I bet if you would look during the Nixon administration or something, there would be a lot of them. It’s kind of like SNL. The cartoons in The New Yorker are all done by different people, so it’s kind of like a variety show. Everyone can find something they’re looking for, hopefully.

You’ve seemed to resist that trend, or at least ignore it. Your cartoons mainly deal in absurdism. Sometimes even straight-up slapstick.

[Laughs] Yeah, yeah. I like that. What constitutes a single-panel cartoon and how they form is a weird thing. I like to make the drawings absurd and that helps me figure them out. In recent years, I’ve done more slice-of-life drawings as I get a little bit older and have more of a real life, I guess. The thing about cartoons is, you can be a clever writer and have a clever line that works, but it’s really hard to make someone actually laugh. Sometimes slapstick is the best way to break through and get someone to laugh.

I always return to a cartoon you drew in 2011 where there are two trees and one is wearing a hat. It’s one of my favorites.

[Laughs] Thank you. I like that one.

What draws you toward absurdism? Was that something you were interested in even before you were cartooning professionally?

Yeah, I think so. I guess so.

Do you find comfort there? Or an escape?

I’ve never thought about it that deeply. I guess I should have before the interview. [Laughs]

I’ve found comedic absurdism to be a lot more appealing as of late. It’s a way to take my mind off all that insanity that’s happening everyday.

That makes sense. I think that’s a big part of it. I do think it’s a freedom for me as an artist. I don’t always want to comment on the hot topic of the moment. I don’t always want to have a take on politics or culture. Not that I don’t have one, but I like making things that don’t sometimes.

It feels freeing to make work that doesn’t relate to hot takes and work that could have been made at any time. I’ve always liked that timeless quality. When I used to oil paint and create more fine art in high school and college, a thing I really enjoyed about a painting or a drawing was that you didn’t always have the direct context of what was happening before or after that image. It was capturing a single moment of time. What happened before or what led to that image could remain a mystery. I’ve always found that interesting and appealing.

How long were you working for and creating cartoons for The New Yorker before you started writing for Saturday Night Live?

I started at The New Yorker in September 2005. I started working at SNL in the fall of 2011.

The SNL schedule is notoriously taxing. How did you find time to draw?

I definitely did not draw during weeks when I was working at SNL. But SNL is only twenty-one or twenty-two shows a year. That leaves about thirty weeks off per year. I would just get ahead. Before starting at SNL, I would just do one batch per week. After I started writing there, then I would start doing four batches in a two-week span. That way, I would be able to submit and have finished work by the time the season of SNL started again.

Is a batch always ten cartoons?

For me, it varies. When I was starting out, I had less of an idea of what worked. You don’t always know what the magazine is going to buy and it isn’t always going to be what you think is the best one. I used to do as many as I could in a week. Maybe twelve or fifteen. I didn’t know the rhyme or reason for why they liked one versus another. As you do it longer, you get a better sense. You go, “These are six or seven that I think are the best. I’m not going to submit these three that I myself can only understand.” [Laughter] There’d be no point in that. For me, a batch has ranged from five to fifteen cartoons. Just depends on the week. It’s fewer now.

Did that speed that is required change the way you technically drew?

I took a few years to develop a style that I was comfortable with and an effective process. I pretty much have stuck to that process for a long time now. Maybe eight or nine years.

What’s the process?

My process now is that I will come up with hundreds of ideas, and then whittle them down to several weeks of batches. Then I will do a real rough version of everything on computer paper with a felt-tip pen. Sometimes those are close to the finished drawing, but sometimes I’m just figuring out the composition and where things will be placed. Then I’ll trace everything using a light box onto better paper, using nicer pens. Then I’ll do an ink wash on top of all that. My roughs that I scan are pretty close to the finished version that would end up in the magazine. I probably do one more cleaner tracing and a cleaner ink wash.

There was a point where I would do thumbnail sketches, then I would pencil, then I would ink, then erase the pencil, then ink wash. That was the worst. When I started using the light box, it turned into a lifesaver. Penciling, inking, then erasing was the worst.

I was going to ask if you were still drawing your cartoons on paper. I’ve noticed that some New Yorker cartoonists you can really tell have gone completely digital.

I’ve never done that before, but Roz Chast has been messing around digitally. I don’t think any of her cartoons are digitally drawn, but I’ve seen some studies she’s done using the iPad Pro and Apple pencil thing. They look cool. I don’t know if I’d ever switch over, but I would be interested. There are certainly times that I’m tracing a drawing on my light box and my hand twitches. I mess up a character’s nose or something and go, “Goddammit! I’m going to have do that all over again.” Digital would be appealing there. I do like drawing on paper though.

What size do you work at?

My roughs are on eight-and-a-half by eleven. I then trace onto nine by twelve Strathmore vellum. I always stay around that same size and framework.

Circling back to your time on Saturday Night Live, is there anything you did during your time there that you’re especially proud of?

My first year, there was a sketch where Jonah Hill was a scientist that taught a monkey to talk, played by Fred Armisen. They had a press conference and the first words the monkey said were, “He sex me.” The monkey just kept adding more and more details about their sex life. That one I was very proud of. [Laughter]

I still think about “Cool Drones” quite a bit.

Thank you! I did that with Rob Klein and Paul Noth, who also make stuff for The New Yorker. That was really fun. Rob wrote all those songs. He’s a very good parody-style songwriter. We did some other animation that never made it on the air. How I got started at SNL was by first knowing Colin Jost and Rob Klein over there. Colin asked if I wanted to do some animation. Nothing came of it then, but it made me want to write longer things like sketches and things that are performed for an audience. I was trying to write a graphic novel for a while before I started at SNL.

Where’s that book now?

It’s in a bunch of boxes. I don’t think it will ever be seen again. It was about God writing his memoirs. It was a different version of the Bible.

Are you going to ever going to go back to it? Do you think you have a long-form graphic novel in you?

I don’t know. I love reading them, but I don’t know. I wasn’t ready at the time. I worked on it for a long time, but I wasn’t good enough or polished enough. Who knows? It was hard to make.

How far did you get?

Probably forty pages or more. It was a fair amount.

Saturday Night Live and The New Yorker are two American cultural institutions. They carry a lot of weight and have a lot of tradition. Do you feel that when you’re there? Did it ever cross your mind that you’re a part of this long lineage?

I guess so. It’s cool. [Laughs] There are so many people who I admire so much and enjoy watching or reading. It’s neat to be a part of that.

They both have that built-in baggage where people believe the best SNL cast was the one they grew up with and the best New Yorker cartoons were when they were the most interested or when they were most avidly reading the magazine.

Exactly!

Do you have a favorite New Yorker cartoonist?

Oh, I don’t know. I find that when I’m by myself, sitting in my house, or just working, I start compiling lists like that. My thirty favorite cartoonists, or something. But as soon as someone asks me about it, I panic. Charles Addams was one I read so much of as a kid. I had a big New Yorker anthology, so I read everybody’s work in there, but I also had a Charles Addams collection. I find that I get another percentage of all those cartoons every time I reread those books. I probably first read them when I was seven or eight.

Those dinner party jokes didn’t land for you?

You definitely don’t get them all. [Laughter] It was fun to slowly build up to understand all the cartoons as I held onto and reread those books.

Do those ideas of “Who’s going to understand this?” or “Will people think this is funny?” go through your mind when you’re making your cartoons?

I trust my instincts. I used to pester my wife a lot. I would carefully read her face as she read my batches. The wording of the captions is something I worry about more than anything. I ask my wife and friends that I trust things like, “Should this line have this word here, or this word?” “Should there be a comma here or here?” I give them like seven options and they are nice enough to humor me.

What’s in store for you in 2018?

We just finished editing the second season of Detroiters. That comes out this summer, I believe. Other than that, I’m working on an animated show, if I can get it all together. I’m pretty excited by that idea. And still making comics for The New Yorker. I’m having a second child too. That’s really my main concern for 2018.

Congratulations! I’m having a kid this year as well.

Oh, it’s the best. Congrats.

I’m a bit nervous…

There’s nothing you can do really but get excited. I am lucky enough to do jobs that I enjoy, but work always has ups and downs and certain stresses. Having a kid provides me with the most happiness and makes me smile the most since I was a kid. I smile every day.

Well, I’m impressed that you can juggle all of these things at once.

Cartooning is really what I always wanted to do. As a kid, if you asked me, “What do you want do when you grow up?” I would have said making cartoons.