The ambiguity of Rachel. Rachel, the maid in Gasoline Alley, is a much more complicated character than she might first seem. On the one hand, King was clearly drawing from the longstanding “Mammy” stereotype in creating her, but she also emerges as a very strong independent character in her own right. As a white American born in 1883, King shared in the widespread racism of the era: he used the n-word on at least one occasion in his correspondence and in a comic strip. He often portrayed blacks with a bemused condescension. But he also had better instincts, rooted I think in his genuine humanism and naturalism, which led him to pay close attention to the African-Americans he came in contact with. In an autobiographical essay, King traced Rachel’s character to a lady he had known when he was an art student in Chicago. “The fact that while going to art school I got a job running an elevator furnished me Rachel for the strip,” King wrote. “Ten cents for a can of beer on Saturday night insured me a generous chicken dinner on Sunday and gave me entry to the kitchen where Rachel presided, big, black and jovial.” I think this comment by King captures the odd mixture in his attitude which combines genuine affection with a slightly patronizing air (“big, black, and jovial”).

Interestingly enough, Rachel was King’s first long-lasting character, pre-dating Walt and Skeezix. King first introduced her as a secondary character in Bobby Make-Believe, a Little Nemo-inspired fantasy strip he started in 1915. King brought Rachel back when he had Walt adopt Skeezix in 1921. Being a bachelor at the time, Walt needed help in raising a baby. From the start, Rachel was a strong-willed character, worthy of respect despite the “Mammy” mannerisms. She was a servant but not subservient and many of the early strips are about how she’s more knowledgeable about raising a baby than Walt. She’s also given an independent life apart from the white characters, visiting her own family in Alabama when on vacation and dating men. In a storyline from the early 1930s, the Wallets hire a white maid to help Rachel. The white maid starts bossing Rachel around, causing Rachel to quit. When they realize their mistake, the Wallets get rid of the white maid and rehire Rachel. Later she leaves the Wallets and gets a job a defence worker and sets up her own household.

Irving Howe once observed that the character Jim in Huckleberry Finn started off as minstrel stereotype but Twain’s artistic instincts were such that he made Jim into genuinely rounded character. I think a similar dynamic is at work in Gasoline Alley.

It may surprise many contemporary readers, but King’s portrayal of Rachel received positive coverage in the African-American press. Rachel was praised as a positive role model in both the Chicago Defender and the New York Amsterdam News (two of the leading black newspapers in America). Writing in the Amsterdam News on May 20, 1944 Constance Curtis was particularly pleased by the way Rachel was portrayed during the war years. “Gasoline Alley which was one of the first, if not the first, comic in which the children really grew, has again made a change for the better. The character Rachel, who in the past has been a maid in the home of the Wallets, is a made no longer. Last year she took a job in a defense plant. This year, with one of the characters home on furlough from the war, she is visited. A look at her home is enough to show you that something unusual in comic strips has taken place. Instead of the usual shanty in which Negroes are always supposed to live, she is housed in an attractive apartment house, with living room furniture that is quite as nice as that of her old employers….When such men as King, who draws Gasoline Alley beginning to lend their hand to fair play for Negroes, we have gained an important ally.”

Black readers and white comics. Finding out what black readers thought about early 20th century comics is hard but not impossible. There are important letters in the archives of cartoonists like Gray and Milton Caniff. Also useful are the African-American newspapers and magazines. Finally there is some interesting indirect evidence as well. In 1928 in Baltimore, there was a “Polly and Her Pals Club,” where African-American dancers wore chic, flapper dresses in the manner of Sterrett’s heroine.

A dance club named after a comic strip was not unheard of at the time. In the 1910s, a “Krazy Kat club” opened in Washington, DC. A bohemian hangout and speakeasy, the Krazy Kat club was busted more than once by the police; its clientele included college kids, flappers, and gay men and women. In the 1930s in Chicago, there was a Krazy Kat club organized by teenaged African-Americans. The existence of the two Krazy Kat clubs and the Polly and her Pals club indicates the appeal the strips had to audiences far outside mainstream white society. In part, these two strips might have been particularly appealing to African-American readers because the cartoonists each had affinities with popular music, including blues and jazz, both of which emerged out of black culture. Black readers might have felt that these strips were closer to their own culture than other comic strip fare.

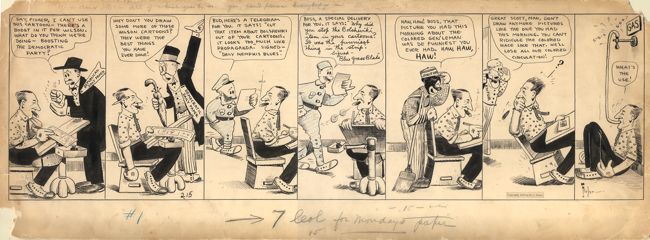

Bud Fisher’s two cents. Peter Sattler has called attention to an interesting 1919 Mutt and Jeff cartoon dealing with these issues. The cartoon shows Fisher fielding conflicting complaints from readers about his strip (i.e. saying he should or shouldn’t do strips about Wilson and the Bolsheviks). In one panel a black janitor tells him, “Haw, haw! Boss, that picture you had this morning about the colored gen’leman was de funniest you ever had.” Then an editor says that “you can’t ridicule the colored race like that. We’ll lose all our colored circulations!” At a loss for how to respond to these varied complaints, Fisher in the last panel is shown killing himself by pumping gas into his mouth.

Cady’s Jews. Responding to an earlier e-mail, the erudite comics scholar Warren Bernard wrote that “long after Life gave up on black stereotypes, they still lambasted the Jews. There was a long strand of anti-Semitism in the old Life, which lasted into the early days of WWI. Many of them were done by Harrison Cady, whose fluffy creation Peter Rabbit masked a vicious view of Jews, a view shared by Forain and Caran D'Ache, amongst others.” As I’ve mentioned before, the most vicious anti-Jewish and anti-Irish cartoons disappeared from most newspapers in the early 20th century, so it is interesting to speculate why they persisted in magazines like Life. One obvious explanation is that newspapers, dependent as they are on advertising, were easier to boycott than magazines, which at that time drew most of their income from subscribers. Again, this shows that there was a range of options involved as well complex motives among cartoonists and editors.