To mark the release of Chris Ware’s decade-in-the-making Building Stories—a box of fourteen print artifacts ranging from cloth-bound volumes and newspapers to broadsheets and silent flip books—The Comics Journal is featuring a series of essays from the contributors to the 2010 volume The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking (University Press of Mississippi). Each contributor is revisiting the argument they made in that edited collection two years ago in light of the newly released work, speaking to the ways in which Ware’s comics have either transformed in that time or are returning to the themes of his earlier publications. We hope these first thoughts give rise to a spirited discussion about a novel that will shape conversation in the medium in the years to come.

Upon learning that his comics would be the subject of a scholarly roundtable—the first stirrings of what would eventually become the collection of essays I co-edited with Martha Kuhlman titled The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking—Ware wrote in an email: “I’d imagine that your roundtable will quickly dissolve into topics of much more pressing interest, or that you’ll at least be able to adjourn early for a place in line at lunch.” This intense self-deprecation comes as little surprise from an author who artfully collated bad reviews of Jimmy Corrigan for its paperback edition, and who warned readers on the cover of The ACME Novelty Report to Shareholders that they would be “gravely disappointed” by what they found inside. Among the suggested functions this latter volume might serve after having been discarded: a cutting board, food for insects and rodents, attic insulation, something to forget about on the floor of your car, and a tax shelter for the publishers.

Back in 2010, I wanted to better understand this rhetoric of failure, and to get at why a cartoonist so widely recognized to be at the forefront of his medium was at the same time so insistent upon his own shortcomings. In part this is merely the result of Ware’s own personal demeanor, an unflagging self-mortification that has served also as a lodestone for narratives about disappointments small and shattering, featuring characters who might be otherwise mistaken for born losers. When Ware is critiqued, this is most often the complaint: all this failure is really getting us down. When asked of other towering figures of American literature, such complaints border on the absurd: Why must Herman Melville subject his characters to such indignities? To what purpose does Edith Wharton tell tales of unrelenting downward mobility? Can’t William Faulkner’s haunted, doomed Southerners ever catch a break?

A much more productive question might instead read: How does this concentrated exploration of failure shape our understanding of these artists’ accomplishments, as well as their relationship to their own work? What Ware holds in common with these and other literary antecedents is the conviction that failure is a creative and generative force in artistic production, that it allows us a lens through which to discover human narratives that resist our peculiarly American insistence on success at all costs (viz. Ware’s rejected Fortune cover, one of the most pointed critiques of the global financial mess we continue to inhabit). Before him, Melville famously wrote that “failure is the true test of greatness,” and Faulkner claimed that he would be judged ultimately on “his splendid failure to do the impossible.” Ware’s rhetoric of failure, I argued in 2010, was an explicit look backward to these earlier, literary claims of productive failure; indeed, he cited the essay from which Melville talked about failure as the true test of greatness when composing his thumbnail history of literature for the cover of a VQR special issue titled “Writers on Writers.” Such failures might be more profitably read as the laments of literary experimentalists straining to break with artistic convention, the protests of those not inured to the ethical disorientation of America’s economic determinists and free-market fundamentalists, or the chronicles of a human condition straining against the inevitable cliff’s edge of mortality. Failure, these artists remind us, is what drives our stories, defines our ambitions, makes us most keenly human.

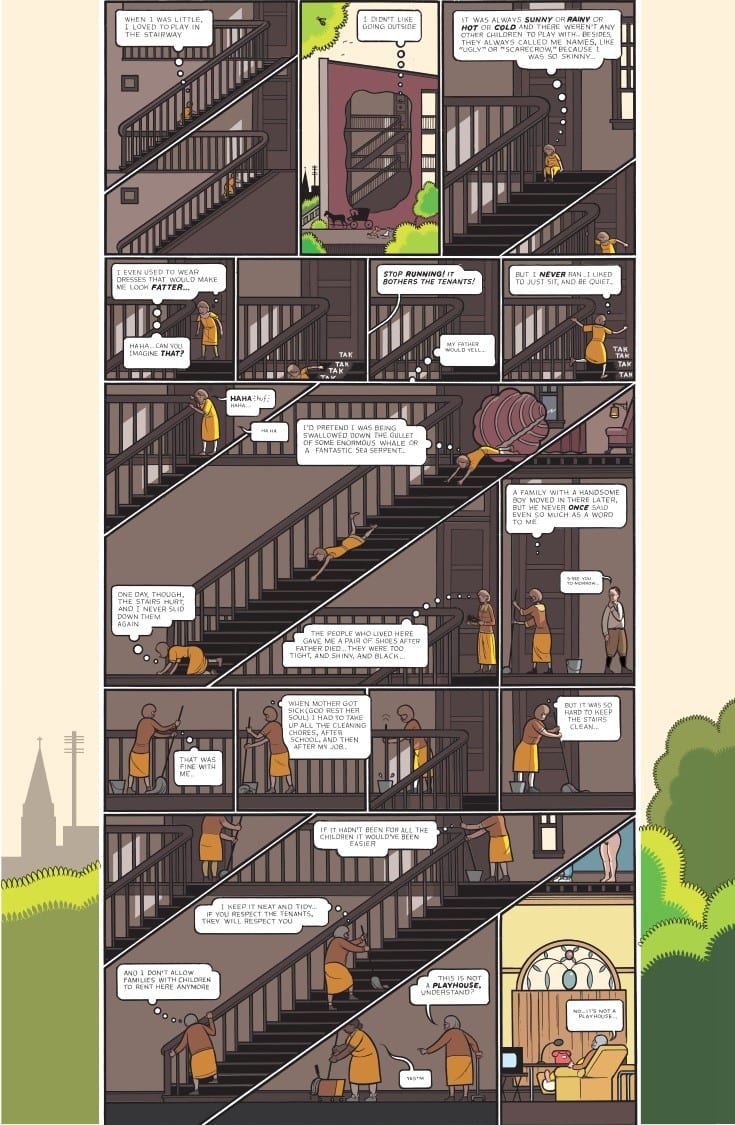

As with Ware’s earlier work, all of these themes course through Building Stories. It is a bravura, medium-altering account of the lives of the residents of a three-story walk-up in Chicago and, later, Ware’s own suburban enclave hometown of Oak Park. Reprinted on the bottom of its box, the advertising copy for BS—the acronym can hardly be an accident—instructs us: “Whether you’re feeling alone by yourself or alone with someone else, this book is sure to sympathize with the crushing sense of life wasted, opportunities missed and creative dreams dashed which afflict the middle- and upper-class literary public.” Indeed the novel’s characters endure failures that we might otherwise be tempted to call ordinary, but for their stories being so richly and fully told. Rather, their often lonely, quotidian lives unfurl into sequences of irradiated, heartbreaking beauty. The landlady on the first floor, who rarely escapes the building in which she was born, is strikingly shown (in a nod to a similarly breathtaking composition by Charles Forbell) at play in the building that will ultimately serve as her tomb, oblivious to the attentions of those who might rescue her from her own circumscribed life.

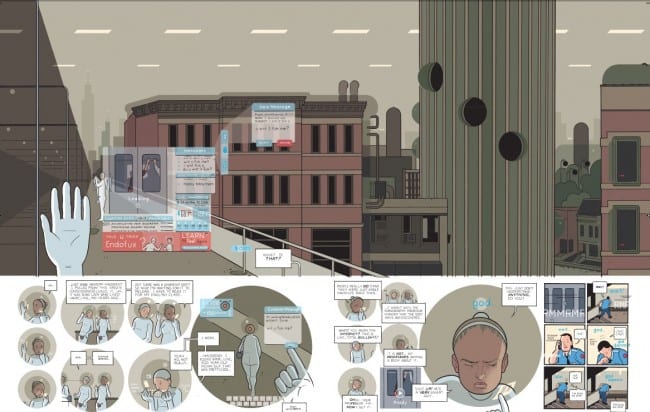

The unhappy couple on the next floor, whose affections we see rapidly disintegrate into unfeigned animosity, nonetheless serves as a single, salient moment of emotional truth in a dystopian twenty-second-century scene devoid of meaningful connections.

Even a neighboring, anthropomorphic bee, the star-crossed Branford—memorably prefigured in Ware’s Penrod the Pigeon from the serial New Yorker covers collected in ACME Novelty Library 18½—receives this rich narrative treatment, before ending up on the wrong side of one of the resident’s sneakers.

Even a neighboring, anthropomorphic bee, the star-crossed Branford—memorably prefigured in Ware’s Penrod the Pigeon from the serial New Yorker covers collected in ACME Novelty Library 18½—receives this rich narrative treatment, before ending up on the wrong side of one of the resident’s sneakers.

But it is with the unnamed third-floor resident, who will come to occupy the center of Building Stories’ and its readers’ attention, that Ware most fully tests the range of his expressive powers and his insistence upon the rhetoric of failure. Ware allows us access to this woman’s life from her earliest childhood memories to her struggles in art school, a particularly mortifying stint first as a nanny and then in a failed relationship tragically concluded with the haunting specter of an abortion, and finally through a later marriage turbulent with the oscillating indignities and joys of securing a suburban household and raising a daughter. Like Ware’s protagonists before her, she struggles with gripping isolation and depression, and failures seem to pile indiscriminately one on top of the other, as when her cat needs to be euthanized the same day she is to give a eulogy at a friend’s funeral.

But it is with the unnamed third-floor resident, who will come to occupy the center of Building Stories’ and its readers’ attention, that Ware most fully tests the range of his expressive powers and his insistence upon the rhetoric of failure. Ware allows us access to this woman’s life from her earliest childhood memories to her struggles in art school, a particularly mortifying stint first as a nanny and then in a failed relationship tragically concluded with the haunting specter of an abortion, and finally through a later marriage turbulent with the oscillating indignities and joys of securing a suburban household and raising a daughter. Like Ware’s protagonists before her, she struggles with gripping isolation and depression, and failures seem to pile indiscriminately one on top of the other, as when her cat needs to be euthanized the same day she is to give a eulogy at a friend’s funeral.

Even amidst all of these disappointments and setbacks, however, our protagonist is allowed near-blinding moments of beauty and joy, ones largely disallowed to Ware’s earlier comics creations. In what, to my mind, is the single most affecting thing Ware has created, the daily involutions of a mother’s care for her daughter are reproduced in a flipbook that distills years of experience into a single, silent sequence. Yet most staggering of all for the novel as a whole is the slow revelation—I think I first realized this more than six or seven books into my own haphazard route through the fourteen collected volumes—that our protagonist may not simply be the subject of Building Stories, but its author as well. Branford the Bee is a fantastic creation she narrates to her daughter, and lines from the speaking building narrative of the New York Times Magazine as well as the narrative of her elderly landlady are both shown to be workshopped in a fiction writing class she takes in the course of the novel’s telling. Her sketches and art school projects surface throughout the novel as well, indicating that she could draw as well as narrate her own life. Ware has hinted broadly at this in interviews, and his citation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire as an inspiration speaks to his desire “to make a book where the book is the reason for its own existence.” So when we see our protagonist wearing a brooch once owned by her landlady, it is not merely one of the epiphanic moments of missed human interconnection so frequently diagrammed in Ware’s earlier work; it may well be a moment in which our protagonist-narrator tips her hand and reveals her own authorship of the comics before us. It is Building Stories’ true accomplishment that this metafictional involution doesn’t read like a gimmick but a revelation, one of a series of experimental pyrotechnics that will transform our ways of seeing and reading graphic narratives in the years to come.

Even amidst all of these disappointments and setbacks, however, our protagonist is allowed near-blinding moments of beauty and joy, ones largely disallowed to Ware’s earlier comics creations. In what, to my mind, is the single most affecting thing Ware has created, the daily involutions of a mother’s care for her daughter are reproduced in a flipbook that distills years of experience into a single, silent sequence. Yet most staggering of all for the novel as a whole is the slow revelation—I think I first realized this more than six or seven books into my own haphazard route through the fourteen collected volumes—that our protagonist may not simply be the subject of Building Stories, but its author as well. Branford the Bee is a fantastic creation she narrates to her daughter, and lines from the speaking building narrative of the New York Times Magazine as well as the narrative of her elderly landlady are both shown to be workshopped in a fiction writing class she takes in the course of the novel’s telling. Her sketches and art school projects surface throughout the novel as well, indicating that she could draw as well as narrate her own life. Ware has hinted broadly at this in interviews, and his citation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire as an inspiration speaks to his desire “to make a book where the book is the reason for its own existence.” So when we see our protagonist wearing a brooch once owned by her landlady, it is not merely one of the epiphanic moments of missed human interconnection so frequently diagrammed in Ware’s earlier work; it may well be a moment in which our protagonist-narrator tips her hand and reveals her own authorship of the comics before us. It is Building Stories’ true accomplishment that this metafictional involution doesn’t read like a gimmick but a revelation, one of a series of experimental pyrotechnics that will transform our ways of seeing and reading graphic narratives in the years to come.

“Everything you can imagine is real,” reads the epigraph from Pablo Picasso on the inside of Building Stories’ box. This seems as true for Ware’s protagonist as it does for Ware’s own accomplishments throughout this extraordinary index of a decade’s worth of work. Rather than dashing the dreams of his characters, as he promised in the instructions to his readers, Ware has given voice to them. By scattering into fourteen print artifacts a kaleidoscopic vision of simultaneous human frailty and possibility, Ware returns us to the governing subject throughout his work to date. Such failures are the true test of greatness.