As indicated in my previous reports, Angoulême 2015 will be remembered chiefly for having taken place under the hovering specter of terrorism, following the Charlie Hebdo massacre and other murders in Paris only three weeks earlier. But even beyond that, it was a memorable year in several respects: a year of protest, reform, and even cautious optimism.

Nous sommes

In addition to the establishment of an ongoing “Charlie Hebdo Award for Freedom of Expression”, which this year was given to the murdered cartoonists after whose publication it was named, Charlie Hebdo was also bestowed a special Grand Prix on Sunday afternoon. Traditionally, the festival has awarded these in anniversary years, thereby honoring an additional cartoonist. The last time it happened was during the festival’s fortieth anniversary, when it was used to solve an impasse in the so-called Academy (which until this year has decided the recipient) and was given to Toriyama Akira (Dragon Ball). Why the festival felt it necessary to give two awards for Charlie this year is unclear—two aren’t necessarily better than one. (This all assumes I’ve understood what happened correctly and haven’t got the two awards confused as one, which proves my point).

Anyway, Charlie was further honored by the naming of a stretch of public promenade after it. Presiding over the inauguration of Place Charlie Hebdo on Sunday was former prime minister and current mayor of Bordeaux, Alain Juppé, along with the mayor of Angoulême Xavier Bonnefont, whom cartoonist and publisher Jean-Christophe Menu had called an asshole to his face in his acceptance speech on behalf of the satirical journal on Friday morning.

The awards ceremony Sunday afternoon was graced by the presence of another politician, Minister of Culture Fleur Pellerin, who stated her government’s intention to create an educational track for satirical cartooning at one of the great schools in France. Not clear which one, but a committee is being formed to address the question. President François Hollande, whose appearance at the festival had been rumored right up to the last minute, took a rain check. This meant that he missed cartoonist Blutch’s acceptance speech on part of Charlie Hebdo which included a quietly intense diatribe against the government for failing to properly support the magazine before the attack, and for letting it do its hard work defending the freedom of expression.

Exhibitions, again

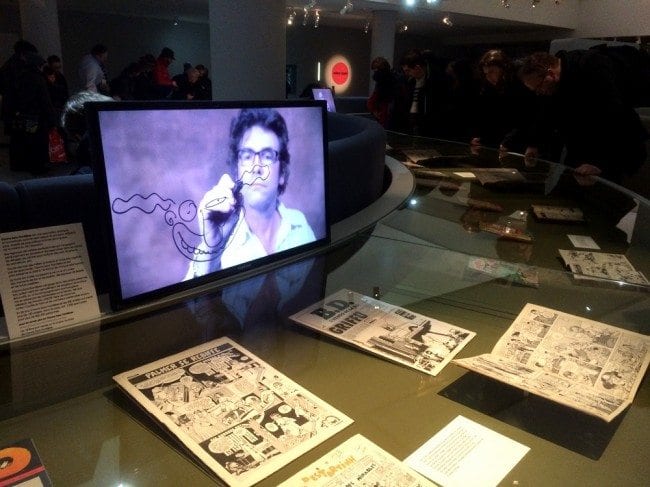

Most moving, however, was the exhibition dedicated to Charlie Hebdo put together in just ten days at the Cité de la Bande Dessinée et l’Image (CBDI) by curator Jean-Pierre Mercier and his team (it runs till March 8). Displayed in the large hall that usually houses the permanent collection, using its innovatively designed snake-like display cases, it tells the story of the satirical magazine from its roots in the first incarnation of Hara-Kiri in 1960, through the founding of Charlie Hebdo in 1970, following the state censure of the issue of Hara-Kiri mocking the death of Charles de Gaulle, to the current version of the journal, founded in 1992. All of this told primarily through the use of the publications themselves—hundreds of individual issues, as well as their many ancillary publications, periodicals as well as books. Videos show the dead cartoonists drawing on glass, while others record historical editorial meetings, press conferences, and so on. A special room off to one side is dedicated to the major cartoonists of the magazine, each represented by a small, but judicious selection of originals.

The chronological, historical display naturally ends with the massacre on January 7, suggested rather than directly described, by the inclusion of covers of newspapers and magazines from that week. Then, at the end, is the survivors’ issue, lit in a dark case by itself. This leads directly to a long, curving wall covered by blackboard where visitors can leave their own thoughts in the form of drawings and text. Simple, somber, and beautiful. I found a cartoonist friend moved to tears in a corner.

Serendipitously, this exhibition was displayed in rooms adjacent to a big Moomin exhibition, showcasing the beautiful, if also occasionally dark and disquieting work of Tove Jansson (till October 5). While far from a perfect show—the display is somewhat overconceived and a little low on originals—it is the perfectly situated and sequenced cartooning antidepressant.

While we’re at the exhibitions, the Taniguchi Jiro show in the old museum building (also till March 8) is impressively designed and contains scores of originals (as well as scores of Photostats), but ultimately disappoints because it never really engages with Taniguchi’s creative process. No mention is made of the involvement, or even the existence, of assistants in the work, for example, when it seems obvious that such collaboration is essential to this prolific, occasionally brilliant and essentially old school-workhorse cartoonist. Procedure as a whole is occluded, with no explanation offered as to the individual stages that lead to the final product—questions about which are begged by the pages on display, some of which are clearly at various stages of completion.

Lastly, the addition of a section upstairs devoted to Taniguchi’s recently completed, commissioned and sadly predictable watercolor tourist’s travelogue from Venice is a painful indicator of how profoundly banal he can be, and to what extent he may be losing his way with fame and old age.

The Grand Prix and other Awards

As I mentioned in my first report, the decision to honor Otomo Katsuhiro with the Grand Prix clearly marks a thaw in the festival’s self-identification as an international event. For decades, the so-called Academy of former winners, who decided whom to award, has kept that particular, strongly symbolic part of the festival’s cultural capital mired in back-patting national chauvinism, only extremely occasionally deigning to consider anybody not French. Through the intervention of some of the younger cartoonists who had ended up in its ranks, this has started to change in recent years, with confusing reforms being imposed, which took away some of the deciding power from the Academy and handed a preliminary list of nominees to French industry professionals across the board.

In a surprising, if perhaps inevitable turn of events, this year saw the Academy eliminated entirely from the process. Instead, there were two rounds of votes by the same large group (a good thousand is the number i saw): during the first each voter was asked to select three names from a longish list compiled by the organizers of the plebiscite, while for the second they had to select one from a shortlist of the three people who got the most votes in the first round. In addition to Otomo, this shortlist consisted this year of Alan Moore, who has stated that he will refuse any such award, and Hermann Huppen, the Belgian cartoonist behind Bernard Prince, Jeremiah and other politically inflected genre series. The latter has had a long and contentious relationship with the festival, in part as the obvious old guard-name never awarded, in part as an avowed leftist with no designs on official recognition of this kind. He had initially stated on Facebook that he did not wish to receive the award either, but was convinced by fans to consider it, should it happen.

Apparently, Otomo won by a narrow margin, which in addition to being as about as just a result as if either of the two others had won (OK, Moore is surely the most deserving, but whatever), is advantageous for the festival. Otomo is an international figure, famous in France since the early nineties, who can perhaps shake off some of the parochialism that still characterizes the festival, and particularly its historical neglect of Asian comics. (Something the new, clearly commercial arrangement with China also attests to). And Otomo might even appear at the festival, if one is to judge cautiously from his gregarious if sedate acceptance video.

Regarding the special award given to Charlie Hebdo, how that got selected and who was responsible is anybody's guess.

As for the Fauves—i.e. the awards given to individual books by a specially selected jury—I have little to add to what I’ve said on previous occasions. Their nomination process and especially their classification system are a mess, but never to the extent where they end up coming across as completely irrelevant. Sure, the award for best "Heritage" book going to Zhang Leping’s San Mao collection might seem like pandering to the festival’s newfound Chinese friends, but it’s a classic of pre-Cultural Revolution social realism and a cracking good comic strip to boot. The award for best debut or “Revelation” went to the interesting-looking (I haven’t had time to read it yet) Yékini – Le Roi des arènes by Clément Xavier and Lisa Lugtin, which is set among Senegalese wrestlers. The commercially-pandering "Best series" award went to the Original French Manga Last Man by Balak, Mickaël Sanlaville and Bastien Vivès, sort of an aesthetes’ action comic, analogous I guess to comics by Brandon Graham or Michel Fiffe in America. And then there's Chris Ware’s Building Stories as the Jury’s selection? Boring, perhaps, but hard to argue with.

As for the selection Riad Sattouf’s L’Arabe du futur for "Best Comic", I refer you to Bart Beaty’s excellent write-up. I would only wish to add that, while this is kind of an obvious, simultaneously intellectually palatable and crowd-pleasing book of the Academy Award-winner type, Sattouf really is a major talent, with a gift for observing telling details and with a provocatively mordant critique of his heritage. A hugely readable memoir just for what it reveals about growing up in Gaddafi’s Libya and the Syria of Hafez al-Assad, but compelling also for the implicit anger it expresses against the cartoonist’s Syrian father, who moved his family there, and for the sense of unresolved discontent with the culture he represents. The first volume of a trilogy, it will be interesting to see if Sattouf will manage to take his autobiography toward greater resolution or not. Either way, it will surely be interesting.

The new management

Without a doubt, some of the reforms and initiatives described above reflect the changes that have happened to the festival’s managing body, 9ème Art+, in recent years. The amicable departure of long-time artistic director Benoît Mouchard for an editorship at Casterman in 2013, and what appears to have been the forced abdication of the Director of the CBDI, Gilles Ciment, last summer after years of acrimony between that independent institution and 9ème Art+, have surely made a difference. The new artistic director Stéphane Beaujean seems to be playing an important role, and recently appointed editorial manager and “Asian coordinator” Nicholas Finet has surely also been contributing significantly this year.

In addition to making the festival financially and artistically viable, 9ème Art+ needs to forge a new relationship with the CBDI and whoever is eventually appointed new director there. From the outsider’s point of view there are several other, ultimately lesser issues that also need addressing, not least the selection process of the Grand Prix and the future role (if any) of the now-alienated Academy. More problematically, it seems the festival has been cooking the books as to its attendance for years. Invariably reporting numbers in the area of 200,000, the festival is now faced with a survey ordered by the regional council which demonstrates that the number of paying guests has generally been closer to 15,000-20,000.

As many had been suspecting, it turns out that the festival—instead of simply counting tickets sold and accreditations given—has been counting the number of entries to each tent during the course of the festival, which is a quick way of multiplying the actual number of guests by a factor of ten. Embarrassing, and not a little sobering for everyone (including yours truly) who has been profiling the festival at the level of the great comparable cultural manifestations in France such as the annual book fair in Paris, which actually has around 200,000 guests, and generally been taking it as an outsize manifestation of the reach of European comics culture. (Speaking from more than a decade’s experience at the festival, I should add that the numbers given in the report seem on the low side, even when one accounts for the large number of accredited, and thus not-counted guests. I suspect the truth is more complicated, and that actual numbers are larger, even if it is clear that they were never close to the official ones).

Protest

As has been the case in the past, the festival once again this year provided the perfect platform for comics professionals to air their grievances with aspects of their industry. This year a particularly visible manifestation took place on Saturday, when some 500 cartoonists and writers representing the newly-formed comics subsection of the writers and composers’ organization Syndicat National des Auteurs et des Compositeurs (SNAC) marched through the streets of Angoulême to protest the disadvantageous conditions under which comics makers work.

The specific occasion was a recent reform of the French pension system for authors and artists. From January 1, professionals in this sector are obliged to submit 8% of their income to a pension fund, whereas before the required percentage was less than half of that. Effectively, this means being forced to give up what amounts to a month’s salary a year for their retirement.

Such government-mandated pension systems are quite normal in Europe and one would think this one fairly sensible in terms of the amount it reserves. The problem in this case is that French comics makers are surprisingly badly paid. Comics theorist and writer Benoît Peeters, who launched a new, impartial and comprehensive industry-analysis initiative at the festival, Les États Généraux de la Bande Dessinée, explains that the creators on average make 8% of the profits on any given comic. This in itself would not be so terrible, if it were not for the fact that sales on the vast majority of comics are very low. An important reason for this is overproduction: where around 700 books were published in 1994, 2014 saw a whopping 5,000 new releases. Apart from the few first-tier bestsellers, this makes the shelf life of each individual release ruthlessly short. And at the same time, no one has yet managed to develop digital sales to a level where it delivers the kind of numbers authors need to survive. Google and Amazon profit while almost everybody else continues producing at diminishing returns.

The Present

The world has always been a dangerous place and satirical cartoonists have long suffered violence, prison, and even death for their work, but for this generation in this part of the world, there is little denying that the events in Paris were a watershed. It’s a new reality, being a cartoonist thus rudely being reminded of your immersion in a globalized world, potentially working at some of its most difficult fault lines. Although Angoulême this year in some ways showed signs of maturation and new possibilities, and despite it being characterized in part by cautious optimism and a spirit of wishing to get on with things after Paris, it will no doubt chiefly be remembered by many as the first collective professional and personal reckoning of what has happened and of the uncertain present in which we find ourselves.

Erratum: The section describing the voting process as published earlier today for the Grand Prix was misleading, in parts downright wrong. As of 2pm EST, it has been amended better to make clear the proceedings that led to the selection this year. The author apologizes for his regrettable doziness.