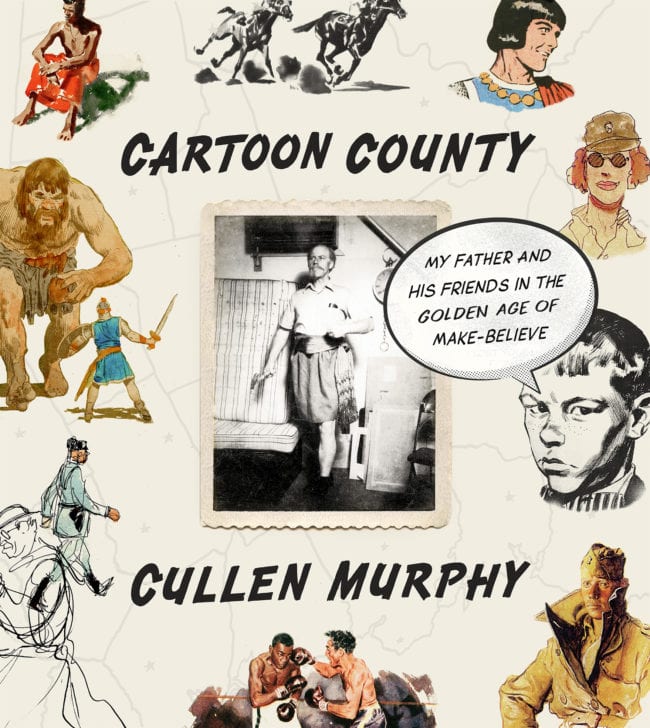

Cullen Murphy has had a curious career. He's likely most well-known as an editor-at-large for Vanity Fair, a longtime editor of The Atlantic Monthly, and the author of books including God’s Jury, Are We Rome?, and The World According to Eve. For more than two decades, though, Murphy also wrote Prince Valiant. When Murphy's father, the late John Cullen Murphy, took over drawing the strip from Hal Foster, Foster continued to write the strip for years afterwards. Foster also mentored Cullen Murphy, who would succeed him as the strip’s writer.

In his new book, Cartoon County: My Father and His Friends in the Golden Age of Make-Believe, Murphy writes about growing up in Fairfield County in the postwar era surrounded by cartoonists and artists like his father. It is a loving portrait of a time and a place that has mostly vanished, and of people who almost all passed away. Murphy writes about working for his dad as a photographer when he was a boy, helping to take photos and serve as a model, about many of the characters who fled New York for Connecticut, events at the National Cartoonists Society, and growing up in what he and his siblings were aware was an unusual environment. Murphy also talks about when he sent story ideas to Foster after his father took over drawing the strip, and how over dinner, Foster told him the script was “no good” – and then gave him a master class in how comics work.

Alex Dueben: You mention in the acknowledgements that Graydon Carter encouraged you to write about this. How did the book start?

John Cullen Murphy: I had spoken off and on with Graydon about the fact that I had been toying for many years about writing something about this unusual background that I enjoyed growing up – and was also part of professionally. He suggested that I try my hand writing about it as a piece for Vanity Fair, and so one summer day about three years ago I sat down and I just started writing and the piece came very easily. Before I knew it I’d written a memoir, although not a memoir about myself, but a memoir about all of these cartoonists—my father and his friends, with of course a special emphasis on my father. It was five or six thousand words, article length. I showed it to Graydon and he liked it. Having gone through that experience of writing it down for the first time, I began to realize that there was a lot more that I could say. In many ways those conversations with Graydon really got the ball rolling.

Yes. It very much is a young observer’s view of what this somewhat unusual, perhaps occasionally bizarre, group of adults is doing all around him. My brothers and sisters had the same vantage point. I think we knew that our upbringing was different, we knew that our dad was doing something different than most dads did, and we knew that the other cartoonists were doing something different as well. So there was a recognition of that. Not that it really played much role in our daily lives, but that feeling never went away, because it is fundamentally true. It was an upbringing that was very much out of the ordinary. Over time as you get older and begin to reflect on your childhood, as every person does, the weight that it carries often increases—the influence on you tends to grow. I mentioned that I’d been wondering for a number of years about whether I should try to capture some of this feeling, and I think it was because the memories of childhood had grown a little bit more powerful as I got older.

You make the point that many people have moved away, many more have died. Middle class Fairfield county has ceased to exist. This is a lost world.

The realization that people that I knew – my father and so many of my father’s friends – had passed away was also part of the impetus here. Every few months you would open the paper or get a call, and you’d hear about someone else who had died. So the sense of this world vanishing – a world that had been very all-consuming, very present, and very powerful – was hard to miss. That formed part of my thinking.

There are plenty of cartoonists who live in New York and there probably always will be, but before the internet, FedEx transformed this world.

Yes. FedEx and fax. And then of course with the internet, it was game over.

There is a nostalgia for this. That everyone lived relatively close to each other and weren’t just talking on Twitter but were actually spending time together.

It was something that had a physical reality. The physicality of work life is something that has changed radically over the past few decades. Simply because technology makes that possible. And yet human beings are physical beings and are social beings and there’s something about people that is drawn to other people in the first place, and to other people doing similar things in the second place. The fact that a lot of cartoonists gravitated toward one another as they began moving out of New York really isn’t surprising. There were tax advantages to being in Connecticut, which is one reason why so many of them were there. But for most of the people who were in that community – and it was a very large community if you add up the cartoonists, their assistants, the illustrators – I can’t help but think that it was kind of a wonderful way to live. How many of us have that opportunity now to consort on a pretty regular basis with the thirty or fifty or seventy people who are doing something like what you yourself do? There aren’t many people in many professions who get to do that. So it was an outlier, probably an outlier even then, and even more of an outlier now.

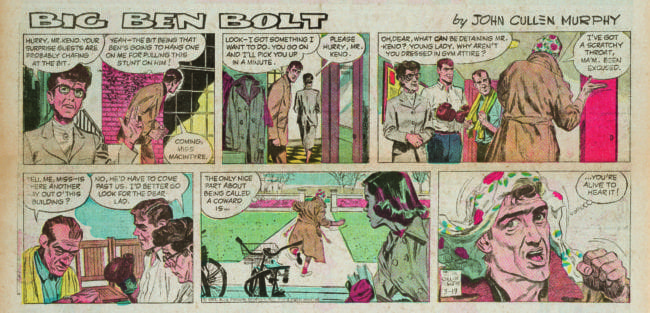

Your father is known for two strips. He spent twenty years drawing Big Ben Bolt and this would have been throughout your childhood. What do you remember about growing up around it?

I remember a lot. I have a different relationship with each of the two strips. We can come back to Prince Valiant. With Big Ben Bolt I was not collaborating with my father, but I was around as a child all during the time he was doing that strip and I was taking photographs for him and I was posing for him, and I was reading the strip, so it was very much a part of my life. Later, with Prince Valiant, I was of course writing the strip and the collaboration took a different form. Thank god I wasn’t posing for him back then. Or taking pictures. Brothers and sisters had taken over that job.

Big Ben Bolt was in a tradition of realistic adventure strips set in the present time as opposed to adventure strips set in the past. There aren’t a whole lot of those strips left. They were once a big deal. In this case Elliott Caplin, who was a wonderful guy and who did a number of strips, including Juliet Jones, had this crazy idea of an Ivy League boxer. Ivy League NFL quarterbacks are more believable than Ivy League heavyweight-champion boxers. Boxing at that time was more of a nationally followed sport than it would become in just a few decades. Of course Joe Palooka had been successful for years. The central figure, Big Ben Bolt, couldn’t stay a boxer forever. Age and biology took care of that. He eventually was transformed into a quasi-reporter/detective with all kinds of scrapes and mysteries that he was involved in. I loved the strip because the plots were changing all the time. There was a lot of opportunity for bringing in new characters, and my dad was great about going out into the neighborhood and finding people with what he always referred to as “interesting faces”. The strip was well-written. It gave my father a lot of opportunity to draw good things. A lot of it was action, a lot of it was faces and people, but a lot of it was also mood setting; my father always enjoyed the mood-setting pictures. Dark night in a seaport, or an eerie landscape, or the office of some grand executive. I think in some ways a lot of the introduction I had to the adult world around me came through that strip.

Your father established himself as part of this realistic school of artists and you talk a little about how they all came up through classical art training.

Your father established himself as part of this realistic school of artists and you talk a little about how they all came up through classical art training.

I don’t know the background of the cartoonists who are active today, but I would be interested in knowing. The cartoonists who were doing strips that were starting in the '40s or early '50s, or taking over strips that had started earlier—a huge percentage were people who had formal art training of some kind. You didn’t necessarily know it from the way in which they drew, but often you did. A lot of them had gone to the Art Students League or other places. They had spent time doing life drawing. To me it was always a marvel that these people—who were doing a sort of work that was definitely very popular, and was also dismissed by the “elites,” even as elites may have read them – were people who were very accomplished. You saw that frequently in the work that they did for themselves. You’d go over to their houses and see something that they had painted or drawn or sculpted, and you realized that whatever it was that they were doing for a living – which they probably enjoyed in its own right – they were also doing other things. As kids growing up, they had had ambitions that were not simply cartooning, or may not have been that ambition at all. That commonality of formal art training was something that I remember noticing early on, or maybe I remember my father pointing it out early on. It’s an interesting facet, because I don’t think most people would jump to the conclusion that they had had that kind of training. Any more than they would jump to the conclusion that Mark Rothko had it, which he did.

And they not only had the same training that people did a hundred years earlier, but they were able to imitate each other and other styles with a lot of ease.

It was fascinating to me at the time. That somebody could look at the work of other artists and to some extent mimic it when necessary. It was an eye opener. Now it makes sense because someone who’s doing representational art is looking at the world around him and representing that world on paper as an artistic act, so why wouldn’t they be able to look at somebody’s else’s work and do the same thing? That said, it’s still an astonishing trait. And it wasn’t perfect. You could always tell – or at least the cartoonists could always tell. When Stan Drake did Big Ben Bolt, the women were far more stylish and alluring. Stan Drake could not draw a woman who was not beautiful, I think. He just had a knack for that. So you could always tell, but the verisimilitude was remarkable.

You don’t talk about this in the book, but I have to ask, what made your father leave Big Ben Bolt and take over Prince Valiant?

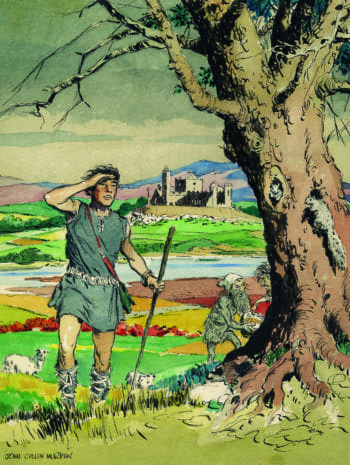

I can’t pretend to give you all the reasons for this – not out of reluctance, but out of ignorance. Here is one obvious thing, but sometimes it’s the obvious thing that gets ignored. For someone who had grown up the way my father did, reading the kinds of things he did, admiring the kinds of artists that he did, the chance to work on Prince Valiant offered a lot more scope than Big Ben Bolt did as an illustrator and cartoonist. It was a bigger canvas. You could do many things that you couldn’t do in Big Ben Bolt. Of course Big Ben Bolt, being a modern strip, meant that you could do things that you could never do in Prince Valiant. But in terms of when you’re sitting down, looking at that big piece of bristol board, and starting to create something, Prince Valiant offered more opportunities to do a kind of illustration that had always appealed to my father. Whatever the weight of other factors were, the significance of this one would have been very large.

I had heard that Foster wouldn’t just write a script but would send layouts to your father and you show an example of this in the book which is much more detailed than I expected.

They’re beautiful.

They’re incredibly beautiful and detailed. What was it like for your father to be working from such a detailed, precise layout like that?

My father loved it. Hal Foster was a great illustrator. My father over time became very close to Hal. They were a generation apart and my father understood that Hal was a master at what he was doing and that when it came to doing this specific strip – as opposed to the many other kinds of illustrations that my father did in his lifetime or the paintings that he did throughout his life – Hal knew what he was doing and it was important to learn from him. I know my father admired those layout sketches that Hal did; he saved them all. Hal did them for probably seven or eight years and my father drew the strip for 33 years. There came a point when Hal let go, but it was never a source of undue constraint. Rather it was a privilege to be able to have this counsel come in this beautiful form.

You took over writing the strip when Foster retired and you have this great account about sending him a story idea and how he tore it apart and explained how comics work and how the strip worked. I was reminded of that famous story of Stephen Sondheim sending Oscar Hammerstein a musical he wrote as an adolescent and how Hammerstein tore it apart and gave him a master class in how a musical worked. Foster seems to have given you a similar master class.

It was. It was on the porch of the Homestead Inn, in Greenwich. There are some things you don’t forget. The conversation could easily have stopped with the words “no good.” In Sondheim’s case, as you know, he went on to become a very close friend of Oscar Hammerstein’s and he took the lesson seriously. I did too. That conversation was such an eye opener because it stripped away the superficialities of the work and went down right into the engine. You need to see how this works. You can put the body on later, you can paint it whatever color you want, but you have to know how the engine of the thing works. I took his advice very seriously. It was so clarifying to have him explain it. The minute it was explained, then of course you think, Oh right, why didn’t I see that? Most people just don’t see these things because they’re not doing it and it doesn’t occur to them to look at the innards in the way in which a practitioner sees them. What strikes me now in retrospect is that Hal was able to explain things so clearly. By that point he’d doing comic strips for fifty years. Some things that are second nature to you are in fact hard to explain, but he was able to explain it.

How did it work when he retired and you took over writing the strip?

I had started sending story ideas to Hal that were just narrative story ideas—written out as if they were extended plot summaries. That was in the early '70s, probably 1972. I was still in college. And Hal began to use them as the basis for continuities in the strip. Then there came a moment when I decided to try my hand at doing them the way he did them, breaking things down into descriptions and text. That was when we had that meeting at the Homestead and he told me that I had not mastered the trick. That would have been in ‘74-75. I kept doing it and got better at it and he began using them in Prince Valiant. I think it was ‘79 when he gave up the writing of the strip altogether and I took over as the writer. As to what happened in the background, I really don’t know. There came a point where Hal sold the strip to King Features, and so King Features would have had a hand in it. By that time I’d been working with Hal sufficiently that I was a pretty good candidate to take it over. Especially because I could work easily with my dad.

You two worked together until he died, and I’m guessing you just gave him a script.

I didn’t do layouts the way Hal did because I’m missing one skill. [laughs] Of course, I did break everything down into panels and sometimes I would sketch out a rough scheme of how something ought to be, but it was very rough.

I ask that tongue in cheek, but the size and the format of the strip changed a lot over the years, which played a role in how both of you worked.

Yes. You had to take certain layout issues into account, but of course strips have always had to do that in one way or another. If you were doing a Sunday strip like Beetle Bailey, say, and you had three tiers of panels, you knew that the newspaper might take the top tier off for space reasons. So you had to have a separate joke in the top tier and then a main joke in the rest, but you had to do it so that it would work with just the bottom two tiers. Comics have always had to deal with the physical demands of the newspapers. I think the real issue for a strip like Prince Valiant came when comics pages began downsizing strips and you had to accomplish as much as ever, but with less. That took some doing. It meant making certain things simpler than they might have been in 1970 or 1950. You always had to keep that in mind. People made that adjustment in different ways. A strip like Hagar, for instance, by the time it came along the downsizing trend was already pretty much in evidence. I may be wrong but I think you can tell just from the way that Hagar is drawn—it’s beautifully drawn, but the simplicity of the line and the darkness of the line is wonderfully adapted to a regime in which strips were getting smaller. It stands out very powerfully. I can’t help but wonder whether that was deliberate. In the case of Prince Valiant, one of the things that my father and I did was use those large panels more frequently. You may remember that every so often Hal would take the bottom two thirds of the page and produce one great big square rather than cut it into four or five separate panels. And he would do a big illustration that would look like something from one of those old Scribner’s Kidnapped or Robin Hood books, illustrated by N.C. Wyeth. Those were really glorious pieces of art. One thing you could do as the strip got downsized was do those kinds of big panels a little bit more frequently. They really stood out on the page just because they were outsized in comparison to everything around. It was a way to remind people that this is a beautifully drawn strip.

You have an exchange with your father in the book that made me laugh out loud: when you write in a script, “a thousand Visigoths suddenly crest the hill,” and your father says, what if I draw ten?

[laughs] Even Hal in 1937 couldn’t do a thousand Visigoths. It was almost a running gag. I knew in my descriptions that I would be suggesting things that he couldn’t do, and he knew that all he was really supposed to do was take the spirit of it and find a way to capture the idea.

After spending so long working with your father, I can understand why you wouldn’t want to continue writing the strip for another artist, but do you ever think about writing comics again?

After spending so long working with your father, I can understand why you wouldn’t want to continue writing the strip for another artist, but do you ever think about writing comics again?

I’ve often thought of writing a historical novel. At one point I thought of writing Prince Valiant novels, but I just didn’t have the time. I’m drawn in that direction. I haven’t done a darn thing about it. In terms of my professional life I have other things I need to do, but it’s an intriguing notion. Would it be an attractive option to do a graphic novel with someone? I think I probably would jump at that opportunity. One thing, though, that readers of The Comics Journal will appreciate but other folks may not, is what hard work this is. I don’t shy from hard work. I’m busy. But comic strips are intense. So many considerations are involved in getting words and pictures on the page in the right way, and within the constraints that are being laid down for you. When you face the decision, Am I going to do this again? It’s both tantalizing and sobering. You have to jump into it with your whole soul.

Fantagraphics is reprinting Prince Valiant right now. Do you know if they’ll be reprinting your father’s run on the strip?

I don’t know. I just saw the extraordinary facsimile Prince Valiant volume that Fantagraphics has published. Have you seen it? Gosh, it’s a thing of beauty.

There was a collection of the early years of Big Ben Bolt a few years ago. Are there plans to reprint any of your father’s other work?

Perhaps this book of mine will give someone some ideas along those lines? One of the good things that has happened is that a lot of my dad’s work has gone to two places. Most of his cartoon work is at Ohio State, at the Billy Ireland collection. It’s such a great thing for the field to have a place like Billy Ireland. The great bulk of Big Ben Bolt is there. The second thing is that his papers and drawings from the war years are all at Brown University, where they’ve been magnificently preserved and are all available online if you want to take a look. There are a couple hundred works there. It’s reassuring to know that all of this material has found such extraordinary permanent homes.

I’m sure that’s especially nice to see because say twenty years ago, that was not a given at all.

It was not. Fifty years ago people’s reaction might have been, what good are these? Mort Walker is one of the heroes of this story, in getting recognition for the preservation of original comic artwork. He would always tell stories about things he’d seen, how originals were being thrown away or used to cover up a stain on the floor. Cartoonists always understood that the original work was great stuff. They loved it and collected it themselves. Every cartoonist I knew had walls filled with the work of other cartoonists. That recognition by them was there, and the missing piece was the recognition by the outside world. That eventually came. People like Mort helped push that, and then some universities like Syracuse and Ohio State, and now when you and I are talking it’s accepted that this material needs to be preserved.