Just when I thought I had completely given up on superhero comics, along comes Copra, a title that pulsates with so much life and imagination that it's nigh-impossible to ignore. Incorporating a plethora of mainstream and indie influences yet never feeling like a half-baked hodgepodge (a problem that plagues most superhero comics these days) the net result is a comic that is both recognizable and yet utterly unlike anything else currently on the market, no small feat.

It must feel like some sort of vindication (or at least a lessening of anxiety) for Michel Fiffe, who spent years struggling to find his voice and an audience until the one-man anthology title Zegas gave him the former and Copra the latter. And that success has led Marvel to knock on his door, and he now writes the teen-team-flavored All-New Ultimates.

With the arrival of Copra Round One, the first trade in the Suicide-Squad-on-acid series, it seemed as good a time as any to talk to Fiffe – who is certainly no slouch when it comes to analyzing and discussing comics – about his history and craft.

This interview was conducted over about a week (give or take a day or two of dithering on my part) on Google Doc and copy-edited by both parties. Many thanks to Mr. Fiffe for being so friendly and engaging. And many, many thanks to Joe McCulloch for loaning me the various (and more considerable than I thought) gaps in my Zegas and Copra catalog.

OK, to start with, how old are you and where are you from?

I was born in Havana, Cuba in 1979, but was raised in Miami shortly after that. My entire family is from Cuba, except with some ties to Spain. I even lived in Madrid for a year when I was a kid. It’s actually where I fell in love with comics, reading translated DC Comics.

What was your first comic? Do you remember it?

I had this thick DC anthology that was sold at Lionel Play World back in the states, but I was three years old so I don’t remember much of it. Later on when I was in Madrid, it was a Dave Gibbons Green Lantern story that was split as a backup in Flash comics. Those Gibbons stories genuinely freaked me out.

What was so freaky about those Dave Gibbons stories? Were these the ones he did with Alan Moore? I’m thinking of that Mongo planet story in particular.

No, no, this was the Len Wein-scripted stuff. It looks like classic American superhero comics. Perfect for DC, perfect for a character who was part of a toy line. But the few stories I had involved a bloodthirsty villain with a shark’s head who made you hallucinate your worst fears and in the end, he killed Green Lantern.

Aside from the great visuals that Gibbons brought to this stuff, these were the stories that helped me learn how to read. They engaged me, narratively and visually. By default, I began to learn the language of comics. That half of a story showed me a three-panel closeup, showed me the surprise at the turn of the page, the way figures can lead the reader’s eye. Simple, simple stuff that of course I didn’t get until way later on. But looking back, Gibbons was nuts and bolts. And the drawing was gorgeous. Plus, that storyline was creepy as hell.

Were you reading or exposed to other types of comics at the time as well? I’m thinking comic strips, editorial cartoons, library collections, etc.

Pretty much just Marvel and DC Comics. When I was back in the states around age 6, I read the Sunday funnies, sure. Then I had to start learning English, and comics definitely made it very easy for me. Comics and television and Garbage Pail Kids.

People diss or sneer stuff like Garbage Pail Kids but they can be a great way for kids to connect with each other and with the larger culture.

Who sneers at those things? Parents in the ‘80s? They’re brilliant -- and yeah, they can help a kid out in several productive ways, but they were just cool. It’s that simple. They were just fun to look at. They struck gold with that and it was just another thing that, at least in my case, kept me engaged on an imaginative level. I would go apeshit when I heard the ice cream vendor down the block. I stole money from my dad for the first time to afford more an extra GPK pack because I was obsessed. I turned to a life of crime to feed Spiegelman’s kids.

I’m assuming your interest in superhero comics dovetails with your interest in drawing and art in general. Were you drawing at an early age?

Yes, all the time. Monsters, aliens, superheroes ... I would redraw comic-book covers. I would sometimes add my own dialogue to the actual comics, or color in certain areas that I didn’t like.

Were you known as the artist in your family or school or group of friends? Did drawing or comics provide any sort of social outlet for you or was it mostly a solitary thing?

It was mostly solitary, yeah, but I never felt lonely doing it. I had a group of friends who would come over and we’d draw comics all the time. We’d create entire worlds, huge rosters of characters, we’d make our own company line.

As far as my parents go, they were very artistic. My mom knew how to paint and my dad drew as a kid but eventually turned to writing. Ultimately, they had to stop actively creating art and focused on employment in a new country. They joined the working class so a little shit like me could get hopped up on Adam Bomb cards and He-Man toys.

Apart from Gibbons, what comics and cartoonists were you into as a kid?

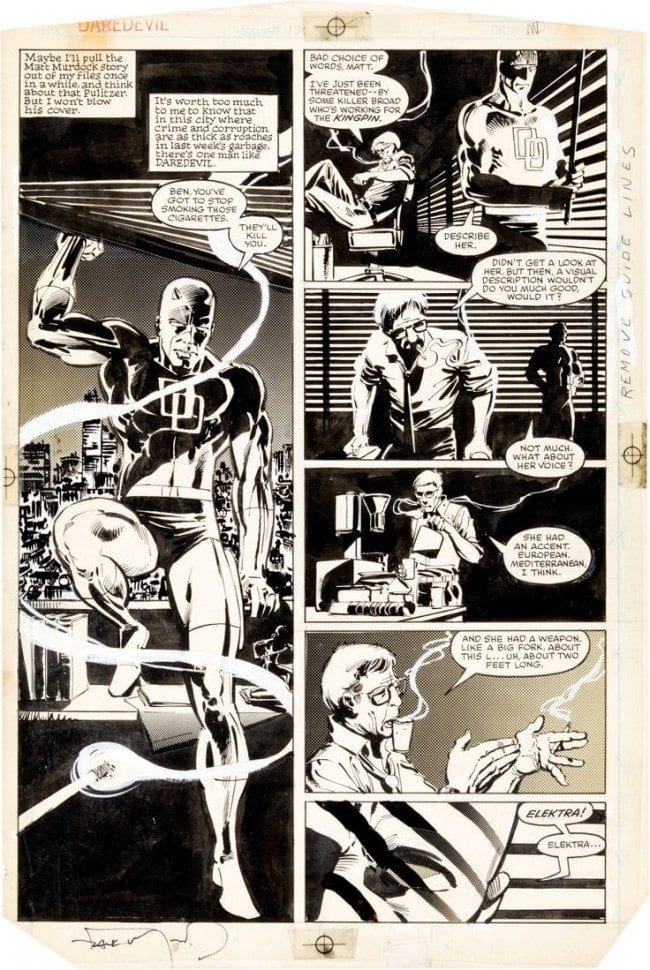

The stuff that really grabbed me as a kid still excites me, I’ve discovered. I always snap back to Norm Breyfogle and Jim Aparo Batman comics. Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, of course. I can write a book on how that impacted me as a nine year old. I was also really into John Byrne to the point where I started drawing crosshatched biceps and open mouths with only lower sets of teeth. I had a few Ditko comics, a few Kirby ... I mean, this is like a list of people I still rave about today. The Ann Nocenti/John Romita Jr. Daredevil deeply excited me every month. No movie or video game or not even any other comic gave me that feeling. Well, except the Justice League & the Suicide Squad. That was the trifecta.

Was there a time where you fell out of comics? I know I had a six-month period where I stopped reading comics only to fall back in because of Power Pack of all things.

Oh, yeah. I binged on shitty and expensive Image Comics, so I purged most of my comics. Then I got into music. The comics hiatus lasted … I want to say a year, maybe a little less. More like a school year. The same friend who got me into music also got me back into comics. Milk & Cheese and Sin City were the ones. One obviously fed into my love for Miller, and the other seemed like the most scandalous, most personalized funny-as-hell comic I had ever read. I imagine that is how people felt when they first encountered MAD or Crumb. I will always love Dorkin for that “Second Number One”. I mean, at that point, I was aware of other comics, thanks to Comics Confidential, which I was lucky enough to catch on Bravo late one night. I taped it, and I would watch it over and over again. It’s where I first learned about the history of comics. That’s where I discovered Love & Rockets! That was it! But it wasn’t until many years later that I actually saw and read and instantly fell in love with the Hernandez Bros.

Which issue of L&R? Or was it one of the trades?

Issue 11. It was on some friend’s floor - didn’t even belong to him. Then at another friend’s house, his older sister had a copy of the Wigwam Bam collection, the one with the orange cover. That hooked me good! The thing was, I never bought comics as a teenager, not on any substantial level. Sure, I bought the occasional Evan Dorkin comic, but I just didn’t have money for these things, and when I did have money it didn’t go to comics books. Love & Rockets seemed so massive, too, like I had to start from the beginning. And I did! Thanks to Barnes & Noble opening up and letting young urchins like myself read tons of graphic novels in their nice air conditioned bookstore.

So at what point did you decide/realize you: A) could make comics for a living; B) wanted to make comics for a living? Was it a specific “a-ha” moment or a gradual discovery?

B) Since that Dave Gibbons comic. A) Since last year.

OK, dumb choice of words there. Seriously though, was making comics always in the forefront of your mind when you were thinking about a career, or at least what you wanted to be doing as an adult?

Well, comics … that was all I ever did. One day in the third grade, all the students were asked to draw life size versions of what we all wanted to be when we grew up. I was the only one who drew myself sitting drawing at a drafting table. What a fucking putz. God, that’s embarrassing. I haven’t thought about that in years. So what age would that be… 8? I suppose that’s when I “knew."

Did you have any any goals along the lines of “I want to draw Daredevil for Marvel” or “Someday I hope to be published by Fantagraphics”?

Both. In that order. I actually had this little plan to “pay my dues” and practice my ass off on a mainstream comic or something, slowly developing my skills. Little by little I would be allowed more creative freedom, until I would be financially able to do my own comics. I was 16 when I had this plan. I was so sure that I would land a Marvel gig almost immediately upon graduating high school.

Did you attend college or get any formal art training?

I attended an art class at the Miami Dade community college for three weeks before I realized that the money I was spending on that class could go to rent money. I soon moved in with my girlfriend at the time and continued to make comics while not working at the local supermarket. My high-school art teacher hated comics and did small watercolor pieces primarily for dentists’ offices in her off time. Whatever I’ve learned wasn’t from academia.

What were some of your first published comics? Did you start in anthologies, webcomics or self-publishing?

Well, in the time from my graduating high school with dreams of moving to New York to the time I was actually living in New York as a published cartoonist, there were many hand-stapled zines, many crummy page samples for editors to see. My first published thing was for a friend’s union newsletter, but as far as comics go? It was in an issue of Free Comics, a short-lived newspaper edited by Aaron Leopold. I’d get a couple of things published here and there, you know, baby steps... really raw, clumsy stuff. I don’t think it’s without its charm, that old material, but looking back it’s a bit boring.

What year would this be about?

2003, 2004. I thought I was hot shit but the world had their eyelids wired shut. I was in my twenties and I was a struggling, arrogant peon trying to work my way up. I had to make comics, I was determined, I had to see this life choice through. And these little spots in anthologies were just enough to keep me going.

So what was the next step for you to becoming a “professional,” published cartoonist?

Well, those little jobs were published but they weren’t professional in that they didn’t pay. It was all free, free, free. That’s the way it’s always been, right? I mean, down to fanzine hopefuls trying to get a gig drawing an Eclipse comic. It’s all “resume” work. Money was never an option, it was an aspiration to be able to live off making comics. And to me, even in my twenties, that seemed like a lifetime away from me. So I took my time on these shorter stories, on band flyers, on illustration gigs. That was the function of an aspiring cartoonist, you just worked and worked and worked and prayed that someone took notice. The problem with that, for me, is that I was too proud and stubborn to really embrace that aspect of it. I hated wanting to be noticed. So as a result, I mostly just worked my ass off in a void.

What was the first point at which you felt you were out of that void?

I don’t think I’ve let go of that mentality, honestly. I feel like I’m able to work the way I currently do by working in a sort of vacuum. And working that way doesn’t lend itself to really connecting with others beyond talking about old comics online. Which I love, but it’s mostly a solo venture. There are pros and cons to that.

It’s funny to me that you say that, because I very much think of you as being part of a certain post-alt-comix generation that isn’t as afraid to cross genre lines or declare an affection for a certain cartoonist or era without being seen as having your foot in a certain “camp.”

That’s the climate we’re in. As far as I know, there was no concentrated effort to make this post-alt-comix thing to happen, it’s just a bunch of cartoonists with a specific skill set, specific areas of interest, and specific ambitions which seems to have manifested into something that produces exciting comics. But what I’m talking about is working as if you’re the only one in the world. I personally need that clear deck. Sometimes that’s just a training method. Other times it feels like very much like reality.

But you were at least for a little while part of a comics collective of sorts, Act-i-vate. Did you get anything positive out of that experience, if not in a “peer group” sense, then in a “step up on the career ladder” sense or even a “hey, webcomics, awesome!” sense?

Well, yeah, all that. Okay, maybe not the “career ladder in comics” part. It was fun at first, getting to draw my comics and having people read it… that was certainly fun. The audience was mostly fellow creators, or the other members, but it was still an audience.

You’re one of the co-founders of it, right? How did that come about?

Co-founder is a lofty term that sounds great on Wikipedia but really I was just in the same group as a bunch of cartoonists who posted their shit on LiveJournal for free. At the time, I had two jobs and not much time to draw comics, so it was a good reason for me to produce something. I took a story I had already started, Panorama, and continued to serialize it online.

Did you have any authority/control per se as far as what could or couldn’t get on Act-i-vate? Were there any rules or guidelines as to what kinds of comics they would publish?

No, no -- not at all. It was really just eight of us trying to keep a weekly schedule. Content didn’t quite matter. Eventually, members kept joining and the thing built momentum and it quickly grew into a real free-for-all. The very thing that may have worked in its favor in the beginning was eventually part of its lack of appeal for me, and that was an absence of an editorial, aesthetic vision.

That’s not to say I didn’t like the comics on there. Lots of good, honest work, a lot of real labor went into that material. Everyone put in their hours and there were some remarkable stories that came from it, but the group had no real fundamental direction. Not many anthologies have that, so it’s no easy task, but the larger the group got the more difficult it became for me to identify with them.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but did you initially start publishing Zegas on Act-i-vate?

Zegas made a double debut. Two different stories, one as a webcomic that went live the same day that the print version hit the stores. That print version is the Act-i-vate Primer, which to my point, was a bit more focused, it was more cohesive, even if only on a superficial level. But honestly, I never considered myself a webcomic artist. I saw it more as the interim before putting my stuff in print. That was the goal for me: print. I wanted paper, ink on paper. Act-i-vate was what I was used to, so I debuted Zegas there. I’ve long since taken down that material.

You’ve taken down Panorama, too, I noticed. Or, at least, I couldn’t find it easily.

It all went down. I didn’t want my stuff online anymore.

Why? Many people see webcomics as a viable publishing alternative, or at least a decent way to get your work under people’s noses, and perhaps, lead to print.

I don’t doubt that it is, not for a second. And maybe I’ll be able to tap into that, but it didn’t feel right calling my work webcomics. First off, I designed my pages with the printed page in mind, with page flips, with those specific dimensions determining the layout. I never took advantage of what a webcomic is or could be and really, and I never really connected with any comic that did take such advantages. As an immediate way to get your stuff out there? Sure, it’s an amazing platform. But that wasn’t where I would comfortably hang my hat on.

Was Zegas received well online or in the Act-i-vate Primer at all?

The Act-i-vate Primer was ignored and the Zegas stuff that was online didn’t make a dent, either. My friends liked it a lot, but it never clicked beyond that. That same story, “Birthday”, was then relaunched for MTV Geek, a site which reportedly got millions of hits a day. Not a peep from that. I knew that the platform wasn’t necessarily the problem, it was the work. It just wasn’t clicking with an audience. During this entire period, I would also occasionally make sample pages for mainstream publishers, just to exhaust every possible avenue in order to try and get paid to do this comics thing. Nothing came of that, either. It was a frustrating period.

So how did you move beyond that?

I thought making better work would take care of everything, I thought that really taking stock of what I wanted from comics would lead me to the answer. I felt like time was running out but I still had this desire to make comic books that hadn’t diminished after all this time and thought that was worth something. Plus I was getting tired of huffing barge at my day job.

“Huffing barge”? What exactly was your day job during this period?

I built props and costumes for sports teams and Broadway shows and for parades. It was a fun job, a creative, challenging job, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do for more than a couple of years. I was there for seven.

So how does that lead to “huffing barge?” I apologize for the segue, but I’m intrigued by the euphemism.

Barge is the highly toxic adhesive that we used to assemble many things. We used respirators and ventilators and all that, but it’s a little much sometimes. We also worked with latex a lot. We made rubber molds, sculpted puppets. It was definitely a career, but I didn’t want it to be my career. I wanted comics.

I see. Carry on. Where were we?

Making better comics as a solution to inner turmoil. What I came up with was this Zegas story called “Arcade”. I just put my head down and tried to make the best possible comic without any plans to publish. Meaning, I wanted to be creative without worrying about getting published or getting hits online or treating it like a resume for editors to consider. I wanted to be as naive as possible and see what happened from not “caring.” Most importantly, I wanted to make a thing that could only be a comic.

I busted my ass on it and for the first time in what felt like forever, I was genuinely proud of the results. Then a close friend of mine suggested self publishing, which to me seemed impossible. There was no way I could deal with the business side of it. The thought of cold calling stores seemed like a nightmare, the thought of spreadsheets was not the most exciting, and really, I was just scared. It seemed like a big job and I felt that making comics was a hard enough job. Plus, I had no idea how to afford it.

How did you get past that financial hump? Did you find a benefactor?

Well, that same friend who suggested I self publish offered to provide the up-front money to get a small but decent print run going. I had no excuse to say no. All I had to do was make an issue’s worth of material and then hope to sell enough copies to be able to afford the next issue’s printing. The second Zegas issue was crowd funded, actually, which goes to show how mismanaged the money side of things was.

Money aside, how did you get over that idea of having to stuff the envelopes and cold-calling the stores? I know that stuff can seem so daunting even in the small world of comics. Did it get easier as it went along?

It got a little easier, yeah. The print run was pretty small but I was overwhelmed. In a good way, I mean. I actually enjoyed the managerial aspect of it, it gave me a nice break from the art and it was… I think there’s a real substantial value to doing this type of work yourself and interacting with the readers and retailers on a consumer level. I learned that real fast. It was a lot of hard work, lots of “boring” work, but it all fed back into itself. It was all part of the picture, part of the process.

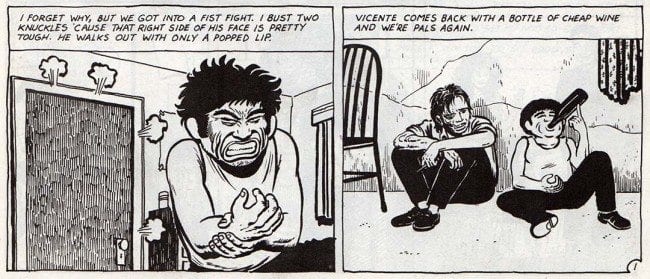

I get the sense that Love & Rockets, particularly the early Mechanix stories with that blend of sci-fi/fantasy and recognizable, real-world relationships and personalities, was a large influence on Zegas. Is that accurate?

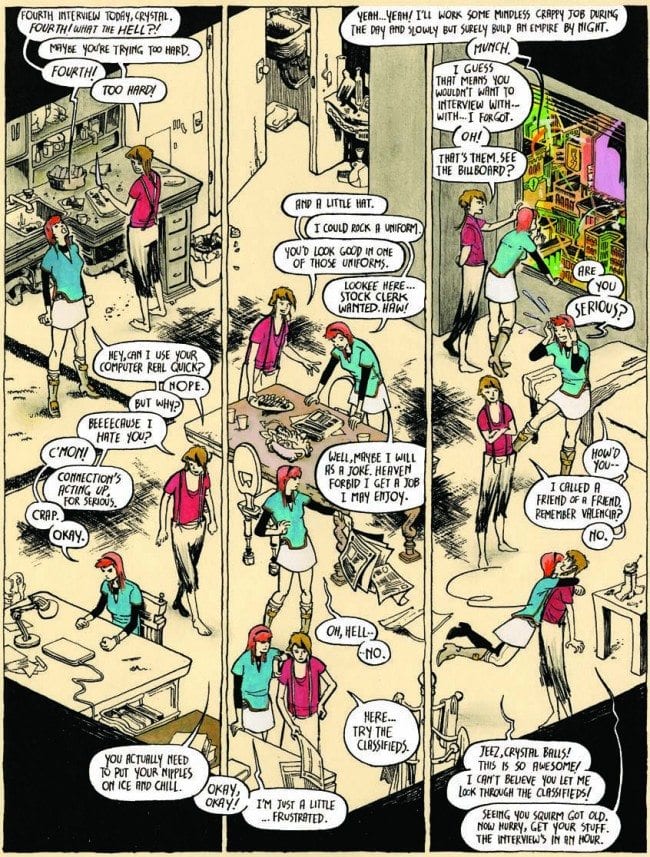

The biggest influence, yeah. I was specifically really into the American in Palomar era, the Flies On the Ceiling era, that stuff was moving well beyond the conventions the Hernandez Bros. had already pioneered. “The Way Things’re Going” - a four-pager - is one of my favorite stories ever. There’s such an undeniable, profoundly beautiful quality to that work that I was completely taken by it. I liked living in their world. So I wanted to tell more down to earth stories but the thing was that I didn’t want to draw only that. I wanted to draw colorful, Cliff Sterrett-type things. I also didn’t want to explain or justify why I was drawing weird proportions and fashions and people. The solution was realizing that they’re just drawings. I liked the specific charm, the specific advantage that approach had. So that mix of naturalism with the surreal really did it for me. It’s not surrealism, really, it’s just… in my hands, it’s goofy doodles that make me very happy.

There’s also an L&R vibe in the size and format of Zegas, it’s similar to those magazine, squarish first run of issues rather than the more traditional comic book size.

That’s the size I was comfortable with even before I discovered Love & Rockets or that Fantagraphics magazine format. All my mini comics were 11 x 17 sheets of paper folded in half which is close enough to that size. It seemed like a best way to maximize the art without it being too huge a book. I still wanted it to be a very casual item to read and to carry around, but not so flimsy that it would easily be destroyed.

I’m assuming based on what you said earlier, that Emily’s job experiences in issue 1 mirror your own, correct?

The job part of it, yes. I’d love to tell more stories in that world.

The main thrust of Zegas seems to be the sibling relationship between Boston and Emily as they attempt to navigate the world around them. How conscious were you in creating those characters of making that the central focus?

I wanted to write a duo, but not a couple or just a pair of roommates. I liked the idea of having this centralized unit with satellite concerns. Having this brother and sister who have a strong bond but still have their own worlds appealed to my desire to keep thing really open. I wanted to tell all sorts of stories through these siblings. I was thinking that one day they may not even be part of the book anymore, that the title characters would take a backseat to the world around them. I wanted Zegas to slowly morph into a complete one-man anthology.

It seemed to me like that first printed issue of Zegas was something of a watershed moment for you. Do you feel that way?

Without question, yes. It was the first time I had made a comic book exactly as I saw fit. It sounds so painfully simple, and yet it took me this long to figure it out.

Why? What held you back before?

Self publishing was… continues to be the linchpin. It holds the entire notion of making comics together because otherwise, I would’ve had to have twisted and modified the concept, the basic thrust of Zegas, into something that a publisher would want to publish. And I was so sick and tired of second guessing what that entailed that I lost track of what I enjoyed about making comics in the first place: to create with abandon.

You published three issues of Zegas, the first two and then a “zero” compilation. Why did you stop? Did Copra take over your work flow?

Copra dominates my schedule, so anything non-related had better be worth it. Like sleep or food or family time. The Zegas world requires a little more care than I’m able to give it. I was primed and ready to go on Zegas #3, actually, but I decided to do something completely different after Zegas #2 as a way to recharge my enthusiasm. That something led to Copra, which instantly took over my life.

Do you think you’d ever return to the adventures of Emily and Boston?

I hope to! I have a few things left to explore in their neck of the woods.

I’m sure there are other cartoonists that sell their comics on Etsy, but I still tend to think of you as “the Etsy guy,” if I can say that without sounding condescending. What made you choose Etsy as a online platform to sell your work? And what has that experience been like?

There I was with boxes full of Zegas #1 and they weren’t moving much. I would e-mail comic shops and small press book stores and try to get them to carry this comic. A lot of them did, most of them on consignment. So I wasn’t making money on any of the units I was moving. My girlfriend Kat had an Etsy shop where she sold several of her handmade jewelry, so I asked if it would be cool if I posted my comic on there as a way to make it easier for people to buy online. I think Big Cartel was around then but I certainly didn’t know of it. And although Zegas was mass printed, it still mostly constituted handmade measures to achieve the final result. That’s been my platform to this day and I don’t see it changing.

I was wondering if you felt it gave you an advantage -- like perhaps attracting readers beyond the indie comics scene -- that other online stores don’t, since Etsy is as much a community/online flea market as it is a web shop.

That non-comics community theory is somewhat true. It does direct people outside of comics on to the book. I don’t think it translates to formidable sales figures, but the exposure doesn’t hurt. My actual sales, or at least the majority of them, are from people that are already comics readers. What it does is that it eliminates several middlemen. I don’t have to live or die by a store’s ordering policy and interest or the distributor’s strict guidelines. Selling a handful of comics to a dozen stores on consignment is not a business model, it’s a hobby. And so I figured out what type of comic I was happy making. It was then a matter of figuring out how to make that into my livelihood.

Do you feel like you have that figured out at this point?

I have my own system that I feel comfortable operating. The first two issues of Zegas was my learning curve when it came to properly shipping and managing expenses while building a relationship with the readers. But yeah, at this point, I feel like the direct nature of Copra Press and its customers ties in to the direct nature I have as a creator with the readers. These are all super fine distinctions, and they’re all important. They all serve this small business I’m running. So for as long as it lasts, this is very much my livelihood.

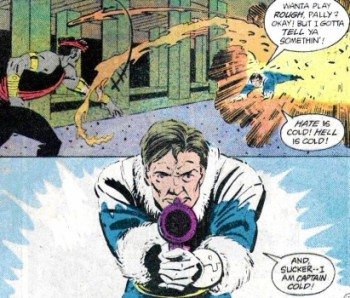

Let's move on to Copra then. My impression is that spun out of Deathzone!, the Suicide Squad tribute you did. Can you start by talking about Suicide Squad and why it had such a hold on you?

It’s a childhood favorite that I would revisit once in a while. And you know how those things go, it’s always better in retrospect. Only sometimes, the thing you liked as a kid turns out to be genuinely brilliant. In recent years, I was happy to confirm that Suicide Squad indeed held up remarkably well. What I mostly connected with was the writing. I think what John Ostrander did, and later with Kim Yale, was the quintessential task of the modern mainstream company writer. He took on a new book on the heels of a major company event and made it into its own little world that was still accessible. It was layered, it was nuanced, it was funny and dark and yet so clearly told that even a nine year old could enjoy it. It handled editorially mandated crossovers with wit and heart and it tied up loose ends for other books and yet it all made sense. It certainly never read churned out. It had so many rich characters, a cast consisting mostly of throwaway C-listers who had previously been lifeless, and Ostrander turned them into real people.

It’s funny. At the time I remember thinking Squad was obviously a cut above the usual DC dross, but for whatever reason, I wasn’t interested in picking it up more than occasionally. Somehow the qualities you describe, while I was aware of them to some degree, they still flew under my radar. Or maybe Legends just put a bad taste in my mouth.

Oh, man, I loved Legends. And Millenium! That’s another thing, I thought I was the only one who liked the Suicide Squad comic.

Back in those days it could be really easy to feel that way about your favorite anything. It often could seem like you were the only one that really appreciated X, whether X was a comic, movie or what have you.

Right, right, and that feeling, in regards to the Suicide Squad, stayed with me up until a few years ago. I mean, no one I knew talked about it. It wasn’t considered a must read, not even as a sleeper hit. If someone was talking about it I must’ve missed it, but on a larger, general platform, it’s still not considered essential reading. So when I met Tucker Stone and we were shooting the shit about comics we liked, I thought he was joking when he said it was his favorite comic, too. But then he quoted a line from one of my favorite issues and I knew he was the real deal.

So how did your revisiting Suicide Squad lead to Deathzone! and in turn lead to Copra?

I needed a break from all things Zegas. That second issue took everything out of me. I needed something looser, something I wasn’t too concerned with. Suicide Squad was on my mind and I had just finished my Wasteland interview with John Ostrander for Tucker’s site, Factual Opinion. So I thought it’d be cool to show my respects to the Squad by doing something. Maybe starting a blog or a Tumblr reviewing the series issue by issue, Douglas Wolk style. Then I thought I’d have more fun drawing pin ups of the Squad. I knew I’d get bored with that, too. I’m not really a pin-up guy, anyway. But what if I made a short comic? Like a short story, a fan comic. Josh Simmons had that Batman comic published, so what would the harm be a short story that maybe literally two hundred people might read? I mean, that was my readership. That was a result of me beating the Zegas drum as hard as I could.

OK, but obviously Deathzone! sparked enough of an interest in that kind of story that led you to Copra.

Well, yeah, the thing was that I had an insanely good time making Deathzone! in my off time. It felt like I was making this really personal, loving “in-joke” that only my friends would laugh at, except it was 0% joke. It wasn’t a parody or an ironic statement. I hate most of that type of material with a passion. Deathzone! was a straight-up tribute. It was supposed to be this super loose thing, but when it was over I was still running on the high of making it. It didn’t reach many people, actually, so I thought that was that. I got that out of my system! Except I hadn’t. I really longed to continue. Obviously, DC wasn’t going to hire me to completely remodel the Suicide Squad in my vision with zero tampering and full creative freedom. Nobody gets that type of blank check. So I flirted with the idea of making my version of the Squad. I mean, comics have a rich history of borrowed ideas. Analogues are our currency.

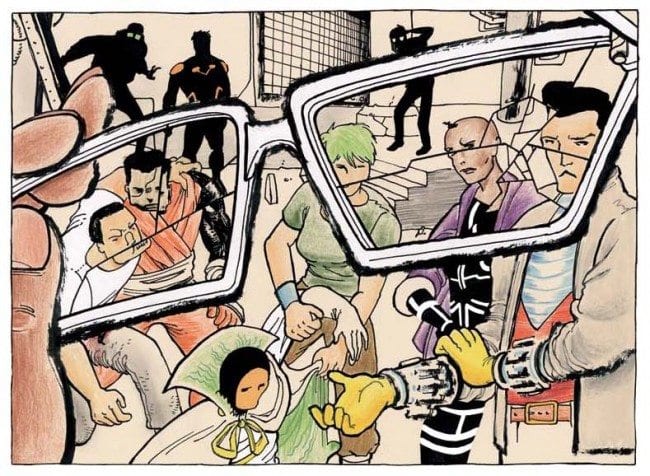

Very true. OK, once you had decided to make your own version of the Squad, how did you go about creating that initial cast and plot? Can you walk me through a little bit of how it went from conception to execution?

I thought about whether I should even do this or not, that was the biggest hurdle. Violent action comics weren’t in my creative wheelhouse, even though some of my biggest influences are violent action comics. So that didn’t seem right to me. Then the whole analogue thing seemed a little cheesy. Sometimes I see analogous books or characters and it’s just painful. There’s this sadness attached to it. But like I said, our comics culture, our culture in general, doesn’t give a flying fuck about that. And that’s what I wanted this comic to be, an avenue for me to not give a flying fuck. I mean, if Stan and Jack didn’t have that concern with the Fantastic Four or most of Marvel Comics, or Alan Moore with anything he does, then who am I to not surrender to this muse of mine?

I have a reason for asking that last question. One of the things I like so much about Copra is that while your influences loom large, it never feels like a pastiche. It always feels like its own thing. I mean, Lloyd is clearly a riff on Deadshot, but he never feels like a copy of another character. That’s a fine line to walk, being cognizant of what you’re borrowing from but still maintaining your own identity. How conscious are you of that line when making Copra?

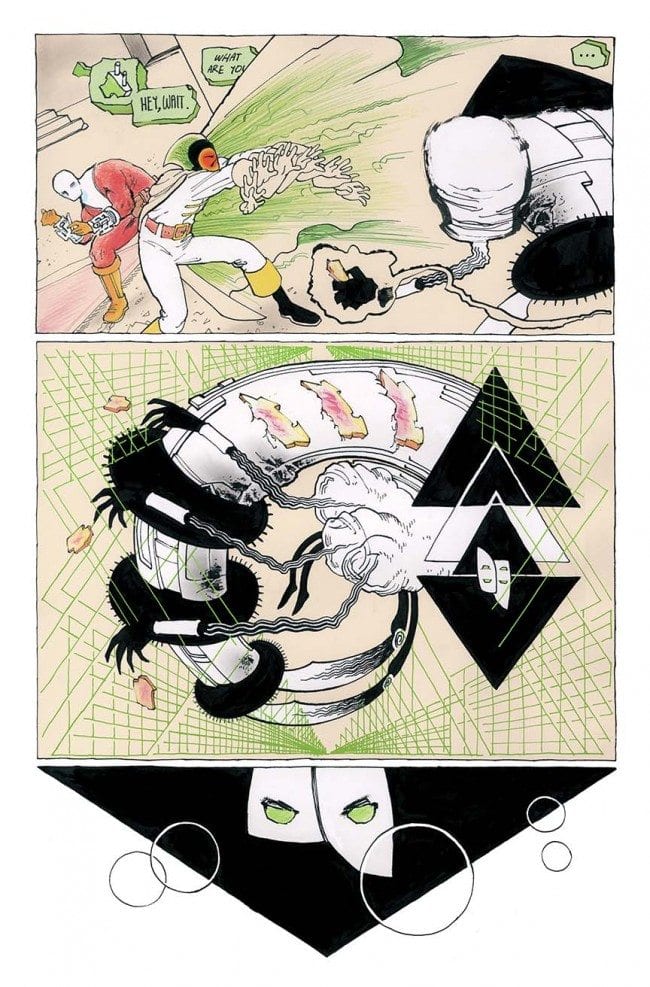

I try not to analyze it too much because I’ll just freeze if I do. When I first started this thing, I jokingly pretended that the publisher had specifically hired me to do this. But that was in terms of just sparking the project and getting in that deadline-is-everything mode. I had to feel like an old ass man cranking a book out because dammit the bills needed to be paid and the next issue’s script is coming and there’s no time to stop -- go, go, go. I had to function like the entire assembly line. I wanted to use that tradition as an underlying identity for the book. That’s why it had to be in single issues, it had to be serialized, it needed to have 24 pages of story, it had to be full color. Back to your question, I find it interesting when readers say Copra is like an '80s comic, which is not my intention at all. I mean, a lot of '80s mainstream comics aren’t great, y’know? I am influenced by the better ‘80s comics, absolutely, but I don’t see them as stuck in a specific time. I think I get the reader’s meaning, which is more in line with a feeling of reading a comic back then, and that’s super flattering, of course, because I really value that experience, too.

Funny, I don’t think of it as an ‘80s comic at all. I mean, you’re clearly influenced by ‘80s comics but it has a very modern sensibility in its execution, at least to my eyes.

I actually think that’s an interesting distinction from my readers, and it’s something I never really talk about. Another thing is when reviewers write: “Copra is great. I mean, it’s nothing groundbreaking, the plot is pretty basic, but boy is it the best comic ever!” That’s so confusing because… what is non-basic? What Marvel or DC comic is not basic as hell? I don’t mean the actual telling of the story, that can be as convoluted and as all-over-the-place as anything, but I’m talking about the premise, the fundamental core of these comics. It’s good versus evil, it’s going on missions, it’s constant fighting. Those are the basic ingredients. Don’t get me wrong, I more than appreciate those reviews, but that specific criticism seems a little off to me. Or maybe it’s actually on. It just doesn’t make sense in the context of the industry.

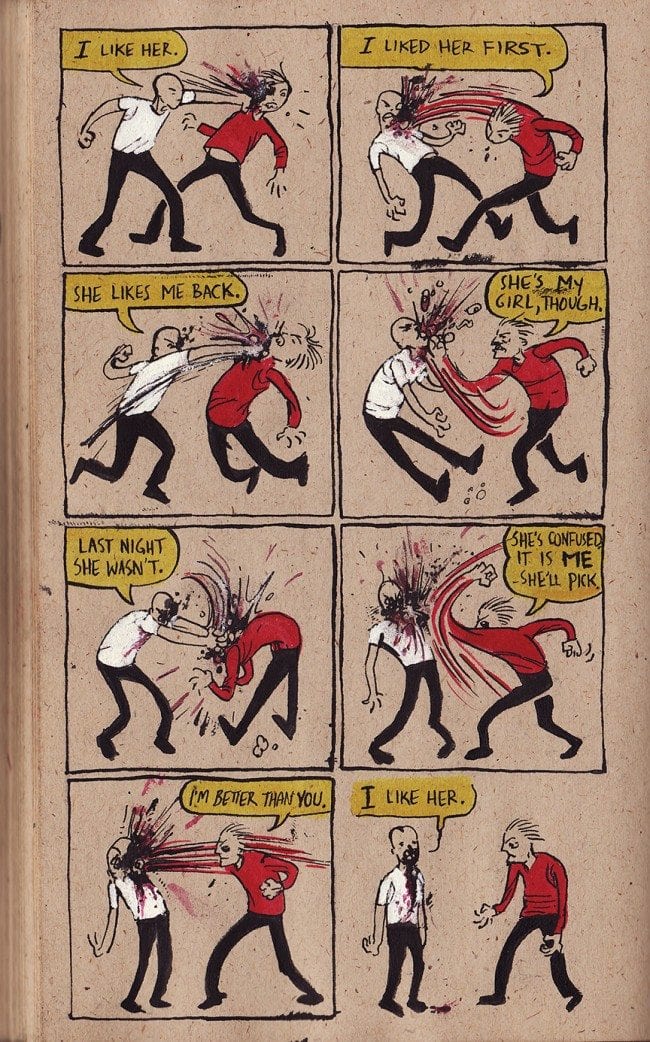

How much of Copra comes out of your interest in depicting action/violence/motion in comics?

A lot of it actually, at least at first. I really wanted to develop different ways of drawing violence, of pacing a fight scene, of rendering the relationship from one object to another in a way that had nothing to do with the way those kind of comics are being drawn now. Most of that came from a desire to actually utilize the drawing, of exploiting the fact that it was a drawing. I think making a reader give themselves to your fictionalized world is a result of every aspect of the story working in harmony, not exclusively how realistic a superheroic body in motion looks. That was and is my primary concern, to create an atmosphere where the reader can lose themselves in, even if it’s just for a handful of minutes.

It’s interesting to me that you say that, because you’re often playing with the grid and breaking the structure of the page, thus making the reader very aware of the comic as drawing (almost breaking the fourth wall as it were). I’m particularly thinking of the “magic ceremony” in issue two, where Vincent is sticking his head and arms through the tiny panels like window lattice.

That’s a pretty innocuous way to declare this thing as a comic book. It is nothing else but a comic book. It’s such a tiny gesture, that moment, but in represents something bigger. It says that the thing you’re holding is not a stepping stone, it’s the end of the line.

Just to be clear, you mean a stepping stone to another medium, like movies, correct?

Right, it wasn’t a recycled video game pitch or something for movie producers to look over. It’s also not so far up its own ass that it can only be enjoyed by a select few. My aim is to be as appealing as possible. So the results may vary wildly, but it should always be clear that it’s a comic book. Having said that, I wouldn’t mind if someone made a Copra fighting video game. This might not be the first time I’ve asked that. Just please, don’t make it look like Mortal Kombat.

Tekken, Street Fighter or Soul Calibur style?

Street Fighter 2 all the way.

Soul Calibur is the way to go, man.

I don’t even know what that is. I’m old.

You’re still younger than me.

I’ll settle for Double Dragon.

Copra has a very large cast and the second “season” of the comic puts a spotlight on the various cast members one issue at a time. How difficult was it to find each character’s voice?

It was easier than I thought, mostly because I tackled every issue one at a time. I gave each character a lot of attention from beginning to end. Once the issue was over, I forgot about them and moved on to the next. It was tricky because I can’t imagine what the reading experience would be like for readers starting with issue 13. They didn’t seem to mind.

How did the deal with Bergen Street Press come about?

It started when they saw that I was selling out of my issues and was unable to meet the growing demand for the material. When I mapped out the Copra Press budget for the year, I wasn’t taking into account that it would take off. I was praying that the same 200 Zegas/Deathzone! readers would stick around for a year. I was concerned with creating something that would hold their interest. So I wasn’t able to afford second printings, or larger printings. I mean, I eventually was able to get to that point, but not in the middle of the month while I’m trying to get a book done. So Bergen Street Comics - Tom Adams and Tucker - swooped in to release the compendium collections which reprinted three issues at a time. Bergen, primarily being a retail store, had a wider reach into other stores, way more than the dozen I was in contact with. That’s when Copra was able to expand. The compendiums were always meant as this placeholder for the real collections, for Copra Round One. But yes, our relationship grew from them helping me out in a bind. I still self-publish the individual issues but Bergen handles the larger accounts.

Since this is for the Journal I should ask you what your working process is like. I’m especially interested in this question though, since, as you noted, you have pretty set, self-imposed deadlines.

Now, before the first issue was even written, I had to make sure I had enough story to fill twelve issues. I had some very minor notes, as I was doing this to be more spontaneous, but I did have some basic ideas. For issue five, to give you an example, all I had written down was “the Japan issue.” That’s it. But that alone was enough to get me excited to move forward with confidence. Turned out to be two issues. When it comes to the actual production, my script is written longhand on random sheets of paper. The writing sometimes occurs on the boards when it’s being lettered. It’s not always that loose, but that’s my version of a second draft, a third draft, and so on. I then pencil very loosely but carefully, not necessarily faster. I want to get things like composition and profiles on tiny figures and perspectives correct. Inking can get super fast but it’s just as neat. It’s just fast. I used to make a line, then stare at it and consider it for hours, then I’d make the second line. That’s out the window. I plow through those pages. Deadlines, man!

What about the coloring?

The coloring is sometimes part of the penciling, but done after the inking. I color on the original pages because it’s just easier and faster. I draw certain backgrounds in pencil or color pencil just to give the drawing dimension. Coloring a group of superheroes every month can be maddening. Tip of the hat to Glynis Wein and Tom Ziuko. I also use watercolors and paint whenever a drawing needs it. I also drop some digital flats to help balance out a page. I try to do all that for 24 pages in four weeks, sometimes three if my schedule allows. It’s pretty hectic but I wouldn’t do it if I wasn’t completely satisfied with the results. Which is funny because after an issue comes in from the printer, I can’t stand to look at it. I just hope that the next issue is better.

You strike me as someone who’s very conscious and thoughtful about how you incorporate your influences into your work. By which I mean, you study certain artists very closely and take very specific things away from them. Is that accurate?

I’m conscious and thoughtful of my appreciation of those influences, but not when I’m actually working. I feel like I’m on autopilot when I draw and it’s all somewhat abstract when I’m planning it out. I don’t think I’m obviously influenced by specific things as I’m making the actual drawing, but yeah, it shouldn’t surprise me that when I draw two figures jumping from rooftop to rooftop, the visual language of Frank Miller will emerge. I can’t really pinpoint what else I do that looks like anyone else, Miller’s just the one I constantly get.

It’s what you’ve taken from Miller that I find interesting. For example, you’ve got that craggy scar face thing where the character’s visage is all these scraggly lines à la Ronin and DKR. I've never see anyone doing that.

I think I know what you’re referring to. The really beat up faces? That I can see. I think Miller’s use of negative space is really effective. His pages, seen as a whole, look really sharp. They flow excellently.

What about Ditko? He seems to loom large for you: I know that you actually corresponded with him for awhile.

Oh, you mean my pen pal Steve? Yeah, he’s an influence, too, but not as much as he used to be. I don’t even see it anymore. I think Walt Simonson is way more of an influence. I really adore and relate to the way he draws anything. His sense of design is incredible, no one touches it. And it’s because he’s not some fucking show off, he’s just making the best possible story. He continues to break ground in regards to layouts and no one talks about it! It’s weird, Simonson should be known for more than being “the nicest guy in comics” or for his Thor run. I feel like he was holding back on Thor. I’m sure it’s because it didn’t fit the character, but then there’s Manhunter. There’s his run on Fantastic Four, Orion, Multiverse… that dude has been next level for more than four decades.

What did you think of Ragnarok?

The first issue was pretty good but the colors give it this overall pukish look. The story, though, is definitely in his comfort zone. It reminded me of that Elric book he drew, which is my least favorite Simonson project. Maybe it’s the subject matter or the way it was written, but it’s a comic I’d rather look at than read. Ragnarok has same vibe but it’s too early to tell. At least he’s writing it himself. It’s funny, about a year ago, I heard him describe this “secret project” as a mix between Thor and the New Gods. So in a way, Simonson is doing his own analogous thing. About time, too.

But yeah, Simonson’s one of the greats for me. I don’t consciously rip him or anyone else off. What I do try to do is imagine what the artist thought about when they drew what they drew. I never try to mimic anyone, but especially not artists like Kevin Nowlan or Tony Salmons. I am so moved by their work that I try to go beyond their style. I mean, I’m never gonna draw like that, so it’s pointless to ape them … and bless those that do; good luck! But why they made the decisions they made? Speculating that is more fruitful than copying they way they draw the corner of a character’s mouth.

What about Mike Zeck or Klaus Janson? I know they figure heavily in your pantheon.

Janson absolutely does, I’d say just as much as Miller. Their combined styles made something that’s difficult to match, it’s truly special. I like Zeck a lot, but if we’re talking about pantheon, I’m more likely to look in the the direction of Norm Breyfogle or Kyle Baker. Those guys are on the forefront of my mind. And I’m talking about the stuff they actually ink, not the digital or painted stuff. Breyfogle’s kinetic pacing and imaginative layouts stand out to me. He’s second to Aparo in terms of my definitive Batman. And Baker is just… we all know Baker’s awesome. He’s so awesome that even he knows it. He should experiment, though, for at least for a week, and stop working digital. Let him get back to using prehistoric tools like ink.

Anyway, me liking all these people, maybe that’s my style. There are so many others I love, like Bernie Krigstein and José Muñoz. I really connect with the lines they make. Same thing with George Grosz and Ray Houlihan and Lorenzo Mattotti, I am positive that they inform my lines, my style.

You know, I recently got some pages back that someone else had colored and while they looked good, I didn’t recognize my “style”, which I’m not aware of most of the time anyway, but this new batch of pages looked like they were drawn by a complete stranger. It made me wonder whether I had any style to begin with. I think that’s because whatever my style is happens to be the sum of its parts, it doesn’t survive that sort of broken down process. Maybe I should stop being a big damn baby and just suck it up. What a problem to have! Oh, no, the way I draw knees isn’t unique!

We can’t all be Fred Hembeck.

Vitas has Hembeck knees. He also has Nancy hair for a skirt.

Actually that allows me to make a quick segue into character design, which I think is a strength of yours. How much time do you put into figuring out how these characters look. I’m thinking specifically of Olivers’ team of otherworldly oddballs.

It really just boils down to what I like to draw. I like to draw things that make me laugh. Vitas made me laugh, all the bad guys are hilarious to me. But I’m not drawing them to be funny, I just get a kick out of drawing them. It’s a challenge to make someone who looks so ridiculous be threatening. But as far as the time I put into it, sometimes it comes immediately, sometimes it takes slight refining. The first four Copra members I drew, shown in the back of Round One, that was a tryout I gave myself. I thought that if those four character concepts look like they’d work well together, if it immediately felt right, then I would take the plunge and do Copra. Otherwise, forget the whole thing.

Copra is a violent book, but its violence is very stylized. Even though it’s for adults, do you have any rules about how far to go and why?

It’s violent, but I don’t think it’s gory or gratuitous or anything, so...

No, I don’t think it’s gratuitous. The story is about violent people with jobs that regularly allow them to be violent. It’s not Fukitor.

I was thinking Faust, but I see your point.

Well, you know what I think of Faust …

I do. I personally like Faust. I like that level of commitment. And when it comes to that level of gore, Tim Vigil’s done it right. He’s gone that far. When I approach violence, it’s not even comparable. I use drawings of violence as a means to an end, and that’s why I don’t put too much of a polish on it. I need it to tell part of a larger whole. I mean, it’s weird because I’m kinda grossed out by the casual gore in mainstream comics. Here and there is fine, but it feels like it’s across the board.

I agree. There’s something off-putting about the way it’s done in, say Green Lantern Corps, that doesn’t bother me in other comics. Maybe because it’s so nakedly pandering?

Yeah, maybe. Why is it okay that Beto makes a guy’s corpse fuck the back of his own head but when someone gets an arm torn off on a monthly basis, that’s gross. Oh, wait, it’s because Beto is a master cartoonist who can eat these guys for breakfast. And it’s funny.

Also, when Beto does it, you’re supposed to be horrified (at least a little bit), whereas when it happens in a DC comic, you’re supposed to go, “Kewl.”

Right. To be fair, I find myself saying kewl whenever a new issue of Prison Pit comes out. Fuck, now I sound like I’m pandering.

This interview is over.

Okay, fine. Prison Pit blows.

I get the feeling that Copra appeals, or at least has the opportunity to appeal, to a wider range of comic fans than your average self-published comic. The indie nerds like myself can groove on the aesthetics of it while the superhero fans can grok the … superhero elements. Has that proved to be true for you? Are you breaking down barriers?

I get feedback from all sorts of readers so ... I guess? The only barriers I’ve broken are related to the miniscule readership I had. “Breaking barriers” seems bigger than it is. It’s much simpler than that: I try my best and hope people like it. I don’t care what their comics pedigree is, all I know is that I’m really happy and honored that people read my book! That’s no bullshit, that is part of the driving force, absolutely. It doesn’t get more direct than that.

What’s your long term plan for Copra? Do you see yourself as continuing it indefinitely? Do you have a definitive end game in mind?

So I told you about me wondering whether I could fill up twelve issues, right? By issue two, I had tentative plans to continue the story past the twelfth issue if I chose to. But it was too early to tell -- I had no idea where this title would be taking me. I may have loved the idea of expansion at that moment, but I was also open to the possibility of being burnt out and hating comics by issue nine. But that wasn’t the case. In fact, these recent focus issues were part of that tentative planning. I do have an ending in mind and everything is building towards that. I don’t want to milk this thing more than it’s worth, either. I try to avoid filler and padding. Even in the slower issues, I want to keep things moving along.

You’re writing a Marvel comic now. How did that come about? I’m assuming someone at Marvel was handed a copy of Copra.

As I understand it, Matt Fraction hipped Brian Michael Bendis to the book and Bendis got in touch with me. Bendis was very supportive, y’know, he really liked Copra. He eventually asked if I’d be interested in doing mainstream work. At first I thought it was going to be drawing a book, or a couple of fill ins or something like that. I was a little worried because drawing two monthly books would’ve been tough. One of them would’ve looked like a child drew it. Marvel wanted me to write a team book instead, which was interesting because I had never written for anyone else before. It turns out that writing takes just as long for me to accomplish as it does for me to draw, so I think I would’ve been fine drawing two books to begin with. Writing kicks my ass.

Why?

Because I’m used to doing it all myself. I don’t usually write full scripts for myself, either, so I had to get used to that. If I have a fully visualized idea and then I have to describe it, that’s the part that takes forever. Not only describing your idea but explaining why it should work. It got easier, but it was a far cry from my scattered bullet points on notebook paper.

Copra is a strictly one-man affair -- the writing, drawing, coloring, it’s all you. How big a challenge has it been to move from something like that to the collaborative world of corporate comics, where the very nature of the business means you have to let some (if not most) aspects of creation go?

It was a big challenge for sure. I knew going in that being open to change is essential, but I wasn’t prepared for just how open I had to be. I even started doing a couple of layouts for the first issue of All-New Ultimates, but I just had to embrace the experience of collaboration. I had to let Amilcar Pinna do it his way. I can suggest things, of course, I can make notes for the art or the coloring or the lettering, but there was a point where I realized I should be more hands off.

Beyond the collaboration aspect, you’re also working for a major publisher, owned by a major media/entertainment conglomerate, and I imagine there are certain rules about what you can and cannot do. Did you find that a difficult transition at all? Did you have any incidents where you were told, “No, Miles Morales can’t do that”?

Rules? Well, I knew that unless it’s part of the MAX imprint, there wasn’t going to be any nudity, cussing, or severe bloodshed. The thing is that Bendis had set up this group of super-powered teens over in his Spider-Man book, so this was a chance to launch their own title with its own style and approach. The line up had more or less been developed before I signed on, and I liked the challenge of writing a teen book and doing it as cleanly as possible. Even though a “Copra treatment” wasn’t discussed, I was allowed to do whatever I wanted, within reason.

Did you have to get up to speed on all the characters’ back stories?

I did have to catch up. I read the Ultimate line back in the day and would drop in and out throughout the years. I had been caught up on Miles Morales and Cloak & Dagger before I took on the job. But yeah, Kitty Pryde was a last minute addition so I had to read a year’s worth of Ultimate X-Men. I was more familiar with the world Bendis created. I was familiar with the Mark Millar stuff as well as the Authority material that inspired his Ultimates run. That sort of direct book-to-book transition was not one I shared, which was fine. Ours was a different Ultimates altogether.

To what extent, if any, did Copra prepare you for handling a team book like Ultimates?

Only in that I had already been juggling several characters at once. I think I went overboard with the first issue, actually. I tried to introduce way too many characters too quickly. I also wasn’t used to handling things like character introductions and exposition in Copra. At Marvel, the clearer it is the better. I can’t play fast and loose with the reader’s involvement. I can drop you in the middle of a conversation and not have to explain anything in Copra - which has its specific purpose - but in All-New Ultimates, you have to know who everyone is and where they’re standing at all times. That level of clarity rules all. So to answer your question, I wasn’t as prepared as I thought I’d be, no way.

Harking back to our conversation about ‘80s comics, I was intrigued to see you doing a Scourge storyline.

Oh, man, I love Scourge. I loved what Mark Gruenwald did with him. The funny part about the Ultimate universe is that a big chunk of their major players were dead and gone. So when I started coming up with ideas for the book, I just combed my comics for characters who didn’t have “Ultimate” versions. I landed on quite a few Gruenwald creations that way, Scourge being top of the list. He’s more of a Bernie Goetz type in our version. I would’ve explored that more if I space permitted.

You talked earlier about working “in a void” and about having to elbow your way (my choice of words) into the market by self-publishing. To what extent do you think this is a result of a specific problem with the industry?

Y’know, others have said that I muscled my way into this and I’d say that’s … I don’t think it’s backhanded -- certainly not when you said it -- but it’s something I’ve heard. It’s fairly accurate, actually. Isn’t that what you do if things don’t go the way you planned, you try to force them to happen? The main thing was realizing that the problem was me, not the industry. I think I mostly have a pretty thick skin but I overanalyze things and I sometimes assume too much. My concern stemmed from all these years of working without seeing any results outside of personal gratification. But I’m stubborn enough to move through that no matter what. Thing is, I didn’t want to be that insane person who is actually hopeless and yet is convinced that he’s a genius and it’s the world that’s wrong. Does that make sense?

Sure. But just because you’re paranoid, doesn’t mean people aren’t out to get you.

That’s a great point, but I was too in it to consider that. I sometimes go straight to the worst case scenario. I mean, this is years of being a young, cocky bastard who thought I’d take over comics at age 18. I was brought back down to earth eventually but goddamn, I felt I was too close to the earth. My dreams and my reality weren’t matching up. As far as the industry goes, I couldn’t be mad at it. It was heartbreaking at times but the industry didn’t owe me anything. Sure, I had moments of bitterness and anger, but what can you do about things you can’t control? I had to learn how to deal with it. Here we have a culture that promotes the idea that if you work hard enough, you will succeed. And I’m not here to disprove that, but I sure as shit was putting that to the test, because even up to Zegas #2, I gave it my all and I truly thought that was the thing. The surge of pride and excitement I felt for the first issue was doubled for the second issue. And when it came out and I tried to spread the word, nothing happened. I couldn’t get arrested in this town. I was like what the fuck -- this is proof that it’s just not clicking. You think I was gonna jump right back to Zegas #3 after that? I was freaking the fuck out, Chris. I figured that, fine, no one’s looking? I’m gonna do whatever the fuck I want before I pull the plug on this comics aspiration thing. Screw it, I’m making a Suicide Squad fan comic then.

Anyway, that’s what I meant about working in a void. All of these concerns - who was I gonna talk to about this with, outside of a couple of close friends? It’s whiny horse shit. I have trouble even talking about it now. Everyone’s got their own problems and gripes. Everyone’s struggling. If you’re in comics, automatic struggle. That’s a given. So I just ate it and kept going. Now I’m fortunate enough to have something that clicked under my belt. It has more than paid off. I really owe it to the readers who buy my book in this super competitive market with their hard earned money. So it’s not like I can now kick back and stretch out and relax. I still have comics to put out. And you know what - all of this can end any minute, just like that, so I’m not taking it for granted. Not a second of it. If it does disappear, I can say that I worked at my dream job. For at least a couple of years I got to do what my 8-year-old self wanted to do: make a living by drawing people beat the shit out of one another.