On the occasion of his new book, The Abominable Mr. Seabrook, Joe Ollman spoke with Brad Mackay about life, art, and cannibalism.

Brad Mackay: As I was prepping for this interview I realized that even though we’ve known each other for years now, I know very little about you. So, let’s try and fix this. Where were you born and when?

Joe Ollmann: I was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1966 on a Christmas tree farm.

What? Really? Tell me the truth.

[Laughs] What do you mean tell you the truth!? It’s true…that’s the truth.

So your family lived on a tree farm, or …

They sold Christmas trees: that was what we did. I grew up in the country; I was a rural child.

But were you actually born on the farm? Like, a home birth?

No, I was born in a hospital, but I mean … okay, jeez. I was born in Hamilton Ontario, in a hospital.

So, you were raised on a Christmas tree farm.

Yes. I was raised on a Christmas tree farm Brad. [laughs] We’re off to a great start!

This interview is over! So, give me a better idea of your family situation. Did your dad and your mom run this tree farm?

Yeah, that was our part-time thing. My dad’s full-time gig was working at Stelco, as most people in Hamilton did at the time.

For the sake of our readers, Stelco was a major steel company in Hamilton which for many years was a heavily industrialized city.

Yeah. It’s a post-industrial city now, but it was an industrial city at the time. And Stelco was gigantic. It was one of the biggest steel manufacturers in Canada, and probably North America. And, y’know, that industry is mostly dead now. All the manufacturing jobs that surrounded it have dried up. But it was a very big part of my growing up, being in an industrial union town.

And for a long time, Hamilton was affectionately known as The Hammer, right?

Yeah, well it’s still called that, but back then it was called that because it was such a rough place, and because of the steel background. In the 1980s and 90s, when the steel industry was dying it became a pretty economically depressed town, so it was a rough place. It was a little bit scabby then.

I remember when I lived in Toronto I would travel to southern Ontario to visit Phyllis Wright or Seth, and the times I passed through Hamilton, I felt a little threatened. There was a sense that I might get mugged for the first time in my life. So, back to your dad: he worked at a steel factory and then also did this part-time tree-growing gig.

That was our summer vacation: harvesting Christmas trees.

And cue the Canadian stereotypes! [laughs]

I’m serious! Our summer vacation was trimming these trees with clippers, making them nice shapes.

This is starting to sound like a Laura Ingalls Wilder book.

It was pretty wholesome. I mean, y’know, we had access to axes and matches and we weren’t allowed to go walk on the road, but we were allowed to drive motorized vehicles and play with gasoline and powder and all that. It was like a normal rural childhood.

And you survived it, which is good.

I survived, yeah.

Because the dark side of rural life is that the chances of getting maimed or killed by farm equipment or in your case, axes, increases for country kids right?

Yeah, like that famous Dave Collier cartoon.

Yes! It all comes back to Dave. As they say in Canadian comics circles, “All roads lead to David Collier”. He’s been in Hamilton for a long time now right?

Yeah. We have a lot of cartoonists living in Hamilton now. Jesse Jacobs lives here, and Georgia Weber just moved here… Marc Bell lives here part-time. Even Seth, who lives nearby in Guelph, likes Hamilton, it’s like his home-away-from-home. He loves to come to Hamilton and take photos.

So, all this talk about Hamilton turning into a burgeoning arts community that’s not just real estate PR?

There’s truth to it, yeah. It’s one of those post-industrial towns that’s riding a kind of burgeoning wave of creativity right now. There’s a lot of cool stores, restaurants, and shops opening up. A lot of artists have moved here from Toronto which is an expensive city to live in, so they can afford to live here and they’ve brought cool things with them, so Hamilton is much cooler than it was when I left here.

It’s changed for the better, although the downside is the rent and property prices have skyrocketed, so it’s hard for everyone that lives here.

So, how would you classify your dad? He was a working guy, a union guy I take it, right?

He was not a union guy, he was a foreman…

Management…

Yeah, a management kind of guy, but he was a very strong … I don’t think he would have called himself a socialist, but he was… y’know he was… and… I am, and my family all are sort of of that [ilk?]. Yeah.

And your mom, what did she do?

She was always a housewife, mom-at-home kind of all of her life. I mean, she worked in a store before she got married, but then y’know she had six kids and she kind of stayed at home and took care of us.

And what about your siblings?

My siblings are all very nice, normal people. I’m the odd one in the family, but they all like me they’re very nice. They’re the most polite, kind-hearted people in the world. They’re very reliable.

So, very Canadian, is what you’re saying.

Yeah, yeah, basically.

What was the breakdown of brothers versus sisters?

I have one brother and four sisters. So, mostly women in my family. I’m the baby of the six, and it’s not that big a family really because my mother came from a family of 19 kids and my dad came from 11, so…

Jesus.

Irish Catholic, man!

I hear ya. I came from a family of two, but I have three kids now, so I’m kind of trying to change the script; the course of history.

You thinking of having more?

No, no! Good God, no! So, when did you eventually leave the Christmas tree farm?

I did, yeah, when I got married. I got married really young, when I was 17. And so I moved to Hamilton then. But yeah, I lived in Hamilton… I lived in the West End, which was the nice part of town, and then after I got divorced I rented a house in downtown Hamilton in, like, 2000. That was a rough part of town. I thought, “Ah, this’ll be grist for the mill, it’ll be hilarious.” I lived across the street from a crack house and I would get propositioned by hookers when I would go jogging, and I got robbed once, and, y’know, got beat up in an alley by like six teenagers.

I got the shit kicked out of me. I got like ten stitches, my lip was split up to my nose… but that was Hamilton then, and Hamilton now is vastly different than that—I don’t want to give people a bad impression.

I got the shit kicked out of me. I got like ten stitches, my lip was split up to my nose… but that was Hamilton then, and Hamilton now is vastly different than that—I don’t want to give people a bad impression.

Sure. Now you just have to deal with gangs of roaming cartoonists. So, when did you say that was, 2000?

That was like 2000. So, 16 years ago.

That would’ve been around the time I was cruising through.

You know, it’s like any city… you’ll have one street that’s a little rough, and then one street over it’s like paradise, nice people living there and everything. So I was just living in a bad part of town. It was just bad luck.

So, was there a point in your life when you realized you were going to pursue art?

I was always a person that was drawing. You know how in school there’s always the competition to see who the best drawer is? I was always in that competition. I wasn’t the first-place kid: I was like, the second- or third-place kid. There was one girl that was better or there was one guy that was better. But I was always a person that liked to draw, and write stories. And then there were comics.

I remember Mad and Jughead and that kind of stuff around, but I didn’t get fully into comics until I was probably like 9. I bought one at a store on a whim, it was a Spider-Man, and it was one of those lightning bolt moments y’know. From that moment on I was addicted to comics. Every cent I had I would spend on them. I could sit there and get my sisters to hold up a comic and I would name the writer, the editor, the inker, the colorist, just based on the cover. I had memorized everything about them, I was obsessed. I would draw a comic, I would copy things and pretend they were mine. I would rip-off people’s work. [Laughs] And I’d say “Oh yeah, I did this.” And it was just a crappy rip-off of other cartoonists.

That’s a noble tradition in comics. [Laughs] When did your obsession with Jim Aparo begin?

Jim Aparo! I love his stuff, he’s great! He’s so underrated! I think he’s not given enough credit. I think he’s the technical equal of Neal Adams, and Neal Adams was… y’know how they always put Adams on the covers because he would draw you in, and then there’d be some lesser artist on the interior. Obviously they thought Adams was a sell, and he was great, I mean he’s wonderful, a masterful drawer. But I think Aparo was his equal. I mean, if you can compare apples and oranges…

In addition to Aparo, you’ve said that Doug Wright was a big influence on your decision to pursue comics professionally. Can you explain Wright’s appeal?

Wright was a cartoonist at The Hamilton Spectator, which was the local paper in town. I would read his strips and notice that he would show local things, and I knew that this guy was definitely not from America. This is an actual guy from Hamilton. I later discovered that he was from Burlington, which is close by so, same difference.

I remember thinking “You don’t have to be from America to do this?” Growing up Canadian, America’s influence was very big in our culture in television and everything else, and we kind of denigrated our own television because it looked cheap and crappy. And so anything that you recognized as being done well, you just assumed it came from America. So, I just assumed that comics were all done in America, I didn’t think there was any [done here]. So yeah, finding out that Doug Wright was from around here was very influential. It made me think “Oh, I could actually do that.” It made it real for me.

So what age were you?

About 10, 11, 12. I didn’t know I was going to be a cartoonist, but I was drawing comics all the time and in high school I was drawing comics. I can remember drawing like Peter Bagge, from Neat Stuff -- drawing stuff that I saw in there for people in class, instead of doing work. It was probably after high school that I started… I would work at night and draw and do things. I tried to do super-hero comics, but they always turned into weird things, more rooted in reality and Kitchen Sink drama-type stuff. So I guess I realized at a certain point that it wasn’t really my thing and I didn’t have the drawing chops to do that kind of stuff well.

So you’re talking right after high school, so 17, right around the same time you got married.

Yeah, the same time I got married I was making comics in my spare time. I finished high school and then worked night-shifts in a box factory and had a kid. But in the spare moments that I had, I had a drafting table and I would draw comics. I still have some of that crap from those days.

So, night shifts in a box factory. I’m going to assume that wasn’t very lucrative.

No, not at all. It was like minimum wage, maybe $3.25 an hour. I guess it seems very David Copperfield-ish or Oliver Twist-ish now, but it didn’t seem bad at the time. I did that for years, then I worked in a machine shop and they were apprenticing me to be a machinist, but I didn’t wanna do it. Then I got a chance to go back to school through a government work program, and that was to study graphic arts. So I did that, and even though it had nothing to do with comics it was enough to get me into making art because I was working for different printers and things like that. And I got a chance to draw things for ads, like shoes or whatever, I had a chance to actually draw things for work, which was great.

I feel like this speaks to something essential to your voice as an artist. It seems to be powered by a blue-collar philosophy; a working-class sensibility. Like, in this case you’re just happy to be getting paid to make something with your talent, even if it’s just a shoe ad.

Yeah, I always feel that. I know a lot of people who are kind of pure, like real “artists,” like “Oh, I don’t wanna draw things that I don’t wanna draw.” If you told me as a 17-year-old kid working at a box factory that, y’know, I could draw a comic for a textbook and live on that for like two months that would’ve blown my mind. I just didn’t think it was possible, so I feel lucky to be drawing anything.

So when did you start publishing your own comics?

The first published thing was in the 1980s. I did a lot of newspaper strips and illustrations in local papers like The Spectator, and then I did a comic strip in there for five years in the 90s and then they changed editors and they ditched my comic, and then I did five years of a monthly in Exclaim! [a long-running Canadian alternative newspaper]

Yeah, they published a lot of alt-cartoonists. Marc Bell was published in there too, and Dave Cooper. It was probably the first place I saw your artwork.

Also, Fiona Smyth, and Alan Hunt.

Alan Hunt, yeah!

Yeah, he eventually got out of the whole thing, but he was a great cartoonist. I miss his work. I loved those little books…I reread them every now and then.

He also designed the first Doug Wright Awards logo. Obscure Canadian comics trivia! I’m curious about the Spectator stuff. What was the strip there? Was it slice-of-life or…?

They gave me complete freedom to do whatever I wanted. So sometimes it was politics: I was a very lefty political guy, so sometimes there would be just like ranting. Sometimes it would be like, y’know, just like stories, like the kind of stuff I do now, just stories about people. So it was just whatever I wanted to do. It was kind of freeing just to do whatever you wanted.

So this was around the same time that you started making your mini-comic/zine Wag, right? Can you talk about how that came to be?

Wag was just a series of little books that I did because I was working at a printing place and I would use the equipment there to print these little books. Then I would bind them myself, I would score the spines with a butter knife and glue them together myself. And they were just full of whatever I felt like, they were kinda like comics and drawings, and my kids’ drawings, and like poetry, whatever the hell I wanted. I sold tons of them at little zine fairs and things like that.

Then around 2000, a publisher in Toronto called Insomniac Press, saw my stuff in Wag and approached me about doing a book. They were looking to do a graphic novel, and I said I could do a book of short stories and they said okay sure, go ahead. But I had seven months to get it done, so I just sat down and did a book in seven months. Just wrote all the stories and drew them all at night.

That was Chewing on Tinfoil, right?

Yeah. It kinda set the tone of all my books: mildly depressing stories that have the relief of humor throughout to make them not unbearable. That was the first proper book, published by someone else. In the 80s I did one of those black-and-white comics called Dirty Nails Comix about a scientist. It was like science fiction but like weird, lefty politics science fiction about a helmet that this professor invents that gets stolen by this CIA type of agency. The helmet can take your thoughts and amplify them and kill people if you wanted.

Then next up was This Will All End in Tears, around 2006.

That’s the one I won The Doug Wright Award for.

Yeah --- I think I met you for the first time at the ceremony that year. I remember having an expectation of what that book would be like, and being caught off guard by it. It was a real step up. The storylines were unexpectedly sweet and off-kilter and you end up sympathizing with characters you didn’t think you would.

Yeah, I heard that from a lot of people. I feel like I wish that I’d have spent more time back then building up a body of work in a similar vein to the stuff that I’ve done with those books. With Midlife and Science Fiction, the stories are character-driven and kind of depressing, but very (hopeful) and human. Hopefully not completely depressing because there’s some humanity in there.

Then you published Midlife, which dropped the connected short-story approach for a single longer-form story. Was that a conscious decision?

It’s different in that it’s a full-length story, but I think it’s in a similar vein to the others in terms of content. But yeah, it was a conscious decision to do a full-length book ‘cause I knew that short story collections are kind of a hard sell. Which is weird, ‘cause some of my favorite comics are short-stories: Adrian Tomine or Dan Clowes’s old Eightball stuff. I love those short pieces. I love that anthology kind of thing, where guys were just doing whatever they felt like doing, and at any length.

And now we have The Abominable Mr. Seabrook, a long-form graphic novel biography that focuses on a very complex and tragically human character that you sort of pulled from the dustbin of history, really. It seems like you’re playing outside of your sandbox here a little bit. Can you explain how you came to this project?

It was just a thing I was researching in the background for years. Seabrook had this really weird, interesting life—he knew all these famous artists and writers—and I was surprised that I’d never heard of him before. So I just started researching him, then bought all his books and I thought he was a very good writer.

When did this happen?

I looked at my notes recently and the first ones I had about him were from 2006. So that’s 10 years that I had it kind of in the background, five years of those being committed to writing and drawing this thing nearly full-time. But it wasn’t much of a conscious decision. I toyed with the idea of doing it, and then I had a script written, and then all the research was done, so I was like “I guess there’s no excuse not to do it.” It was daunting though, because it was big. 300 pages, y’know. I discovered Seabrook in an anthology of zombie stories edited by Peter Haining called Zombie. The story was “Dead Men Working in a Cane Field”, a famous Seabrook story that’s an ostensibly true story of these zombies working cutting cane—it’s great. But what really interested me the bio of Seabrook in the book which gave me a glimpse of this guy; all the people that he knew and his life, plus he was an alcoholic, a cannibal, a bondage freak, and all this stuff.

Well, I can see why he caught your interest. He’s very interesting and engaging, but he’s also a refreshingly unlikable protagonist for a biography.

Yeah. I think he was probably a lot of fun to hang around with and that’s why I think all these famous writers befriended him and remembered him. A lot of them wrote about him in their own autobiographies or memoirs. But like any troubled person, I think he would have been super hard to live with. At the beginning of the book I think I liked him, because he’s a fun guy and a crazy adventurer, and he was very honest about his vices and that kind of stuff. But I think I liked him a lot less by the end of it.

There’s definitely a point in your narrative when his eccentric shenanigans lose their charm and stop being amusing—even to him, I think. It’s a very layered, complex portrait of the man—it feels rich, and true to life. It reminded me of that biography of Orson Welles written by that British actor.

Simon Callow? Yeah, that’s a great book.

Yeah, right? Callow does such a good job of confronting all aspects of Welles, who was a truly complex character, and the result feels very rich and completely human. It’s like the opposite of the standard Hollywood biopic film formula, where it’s just a set of arranged scenes designed to elicit sympathy, while omitting anything that runs counter to the rags-to-riches narrative. You avoid that in this book: you’re not afraid of tackling his darker sides. You confront his rampant womanizing, and even his cannibalism which he exploited in a very strange way.

But he was honest about that in his lifetime; by the time he wrote his autobiography at the end of his life, he told the truth about that cannibalism. But, I mean, yeah, in a book that’s non-fiction fudging with the truth is kind of like the worst thing you can do, and he did a bit of that.

The thing about that story is that, yes, he lied about eating human flesh in his book. But he felt guilty enough about it that he found a workaround that somehow manages to be more disturbing than the story he fudged in the first place.

Yeah. In the context he claimed to have done it in there’s a real cultural significance to it: with these guys who were actual cannibals, culturally. But that fact that he does it when he comes back to an urban center like Paris, and gets his friends into it as well…

Just to be clear, Seabrook gets duped in Africa by some guys who claim they’re feeding him human meat.

Yeah. It was like an ape, like a great ape, that’s what he described it as. He could tell by the finger bones, which he noticed were longer than a human’s.

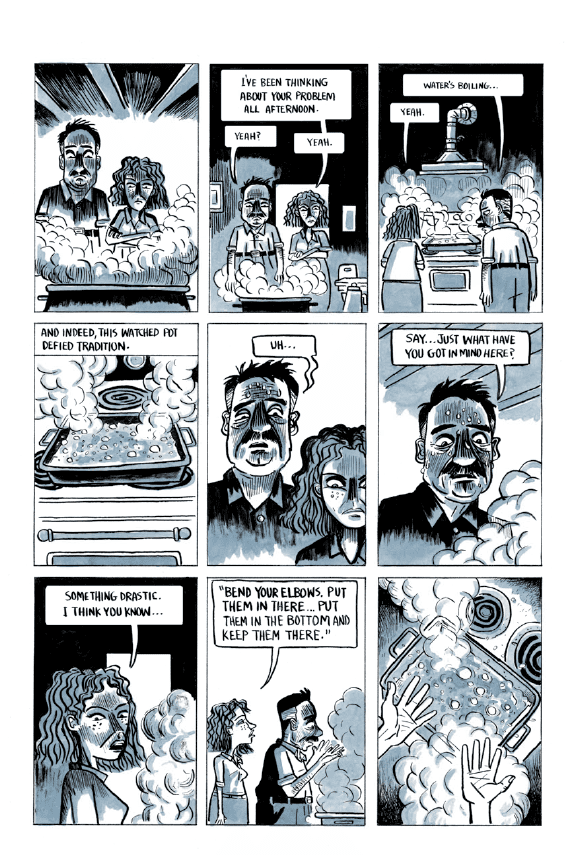

But he writes about it in a best-selling book anyway, describing the taste of human meat. But he was bothered by this fib enough that he concocts an elaborate and highly illegal scheme and ropes in unwitting friends, to actually consume human meat. In short, he gets back to Paris and feels so bad about lying about being a cannibal that he reaches out to a mortician —

Through a friend, yeah. He acquires a pound of like, neck meat, I read in one place. From the neck! And then, yeah, his translator Gabriel D’Hons [?]let him use his chef and his kitchen, and his chef cooked it in three different dishes—three different ways—and then he served it to him and he ate it in front of his friends. BY doing this, Seabrook felt like he was being true to his lie. But the crazy thing was that Seabrook wasn’t going to tell his friends that it was meat from a human; he said it was from a rare African goat. Then one woman was like “I wanna try some!” and Margery Worthington, Seabrook’s second wife, was like, “No! Don’t touch it! It’s filthy!”

It’s one of the most compelling parts of the book to me, because it says so much about his personality and disposition.

Yeah, it’s a crazy story. But a part of me thinks it’s crazy, and then another part of me as a vegetarian of 28 years, doesn’t think it’s any weirder to eat human than it is to eat a dog or maybe a cow. So it’s not a big deal, if someone’s already dead. As long as, you know, you aren’t going out and consciously murdering them.

Stop pandering to your cannibal demographic.

I’m not pandering! But I just…I don’t think it’s that bad I suppose.

To me the story speaks to his twisted kind of integrity. You argue that he was insecure about his reputation as a kind of “yellow journalist”, a real exploitation artist. In this case he really leans into it: it’s like he figures “Well I told them I ate human flesh, then I better damn well make sure I do it.”

Yeah, it’s a weird thing to do. And it’s weird to be so obsessive about making it true, y’know. Part of me doesn’t seem like it was about making it about editorial authenticity, I think it was more about him, like, he wanted to do that. He strikes me as one of those guys who would try anything once y’know. And so that’s why I think he wanted to do that. And then when he didn’t get the chance he felt kind of ripped off, and so he made it happen.

So, tell me about your research process with the book.

I have no experience writing this kind of thing; I’m not a researcher or an academic or anything. So I just kind of half-assed did things and tried to keep it organized and tried to keep my sources straight and all that. I relied heavily on Seabrook’s biography, No Hiding Place, which is a great book. Then his second wife Margery wrote a book called The Strange World of Willie Seabrook in 1966 which was her biography. They’d divorced in the 1940s, so this is years later and she was still thinking about him, you can see that she still felt fondly towards him. She didn’t write any (rancour) or anything but she was honest, she was very honest. And you would find very different versions of the same story in the two books.

I also read her papers at the University of Oregon. I went down there for four days and went through her papers, and her (diaries.) It was amazing and kind of depressing. You know, living with an alcoholic and putting up with his bondage stuff, which she wasn’t really into but she tolerated because she loved him. So there’d be all these diary entries of them drinking too much and then this half-hearted bondage… it was fascinating.

You also went to North Carolina for research right?

Yeah. I went to North Carolina—there’s a collector there who had a bunch of writing and unpublished stuff and paraphernalia, like photos and things. So that was a great thing too, I got a lot of info out of there, that was really helpful.

At some point in this 10-year process you decided to stop drinking alcohol, right? Can you talk about that a bit?

I quit drinking somewhere around the middle of the book. I think I’m going on four years of quitting booze now. I don’t think I stopped because of the book, but maybe it made me think about it, because I was constantly writing about someone who would y’know, drink til they puked. I wasn’t drinking til I puked or anything, but I drank a lot: all the time, like at night when I worked. This was the first book I drew sober. People have been telling me the artwork in this book is vastly improved compared to my other books, so maybe drawing without sipping bourbon all night has improved my artwork. I would suspect that that’s probably true.

We’ve talked about this before, and you’ve always stopped short of calling yourself an alcoholic.

Yes. I would say I was a person that drank a lot, but I was drinking a lot less than I used to after my divorce. And for me it was like, oh okay, I’m getting older…I was almost fifty at the time. And I was like, You’re not a kid anymore, you can’t just live rough like that all the time. So it was a conscious decision. It also happened right after my dear old Dad died. My Dad wasn’t a big drinker, but he was diabetic, and alcohol is just pure sugar so… I quit eating candy too, that was another thing, I was just trying to like—I have a young kid, I have grandkids, I’m trying to be healthier, y’know. I tried it for a year with no booze, and I felt better and I saved a ton of money. I wasn’t a cheap drunk, I was drinking good booze, I was drinking good bourbon at night, or good single malt.

Boozing ain’t cheap, that’s for sure.

There’s no real advantage to it. Like my wife says, I am the ultimate all or nothing: I’m either gonna drink everything, or I’m gonna drink nothing.

A total absolutist. So given this change of heart you had, was it difficult for you to have to depict Seabrook’s numerous failed attempts to sober up?

That was very depressing for me. Not as someone who drank a lot, but just like as a person. In his book Asylum he writes about checked himself into a mental hospital for rehab and to get dried out. He was dying at this point, he was drinking himself to death basically. So he spent seven months in Bloomingdale’s mental hospital in New York, and he gets and says “I’m cured, now I can take a drink or two and stop.”

I guess at the time not much was known about alcoholism, so he didn’t know that you really can’t do that. If you’re an alcoholic, you’re an alcoholic. You don’t get cured; you learn to not drink. So that was very sad for me, because he was completely dried out and doing good, and then he made a conscious decision to go out and buy booze and start drinking again, because he felt kind of emasculated by not drinking.

And as a tough guy, I can see that cause I sometimes feel like that. I feel like that about not smoking, because I was a very macho young guy. I was like “Ah, I smoke two packs a day, no filters,” and “Oh, I drink whiskey all night.” So you can see that if you don’t do those things, you just have to find something else to identify yourself with. That’s the secret, and I don’t think he could do that.

Yeah, there’s a strong pathos there in his eventual downfall. I think that was a real masterstroke that you shied away from romanticizing that aspect of his life. You disabused us of the notion of the stereotypical, old-school, happy-go-lucky drunk writer.

Yeah, in most movies and books, even ones with anti-drinking messages, they always make drinking look really good. It never looks as bad as it should; y’know, they don’t show people waking up in a pile of piss or something. That’s literally what was happening to him. In movies they show characters being unreliable and missing kid’ birthdays—

Buying a dog in the middle of the night…

Exactly, all the crazy things that people do when they’re not sober. But, I just tried to make it realistic and true to his experience as possible. It wasn’t pretty! It’s like Hunter S. Thompson, who is a similar character to Seabrook. I would love to know if Thompson was interested in Seabrook or admired him, because I think Seabrook is a progenitor of the Gonzo movement; of throwing yourself into the middle of the story. Because that was always Seabrook’s thing; he tried to throw himself into the middle story and make himself the story.

And Thompson was one of those guys who was all about taking all the booze and all the pills. I eventually heard an interview with his kid, and y’know he was a very hard person to live with, obviously.

Completely unreliable, yeah.

That’s how he described him. And in the end, Thompson ended up blowing his brains out. He couldn’t go on.

Exactly. That moment when Seabrook chooses to take that drink…he might as well have picking up a gun.

You wanna stop him. It’s like watching a horror movie, you’re just like, don’t do it man.

You talk about the fact that Seabrook always felt tied-down by his reputation as a gutter journalist; in reality he was kind of ahead of his time. There’s Thompson of course, but he also brings to mind George Plimpton, whose entire career was based on thrusting himself into new and unlikely situations, and then writing about it. I guess maybe Plimpton perfected the formula; he didn’t drink himself to death and didn’t alarm people by dining on human neck meat. Didn’t Seabrook manage to offend Aleister Crowley with his cannibalism?

Oh yeah that was interesting. After Seabrook died Crowley wrote in his diary “the swine-dog Seabrook is dead at last.” [Laughter] I don’t know if that was sarcastic or if he really hated him, it’s unclear—they seem to get along and they hung out together, like he came out to Seabrook’s farm in Georgia and stayed there for a couple of months I think and so yeah, I guess there must’ve been some falling out at some point.

Didn’t he despise Seabrook after he read about the cannibalism?

No. Crowley thought it was disgusting that Seabrook would let his pet dog lick his face. [Laughter] So Crowley, a guy who does black magic with Eucharist wafers and semen and blood, didn’t like him letting his dog lick his face.

It figures. Seabrook was probably waiting for Crowley to be shocked at his increasingly eccentric adventures, then this dark beast of a man comes to his farm and gets grossed out by a dog kiss.

Yeah, Jesus Seabrook: don’t let your dog lick your face man! I guess he had his limits, you know. [laughter]