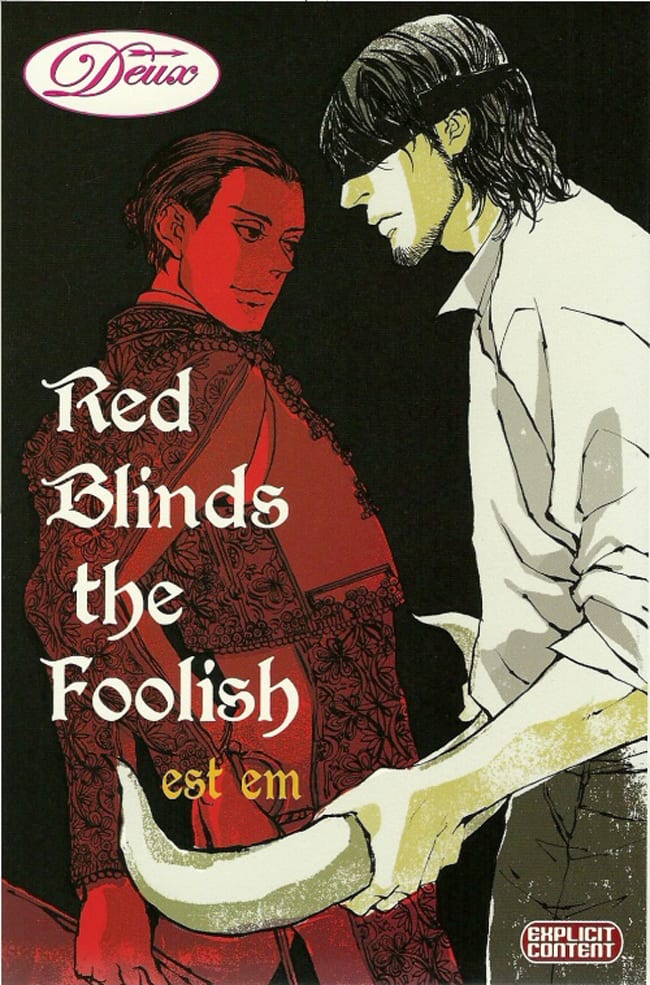

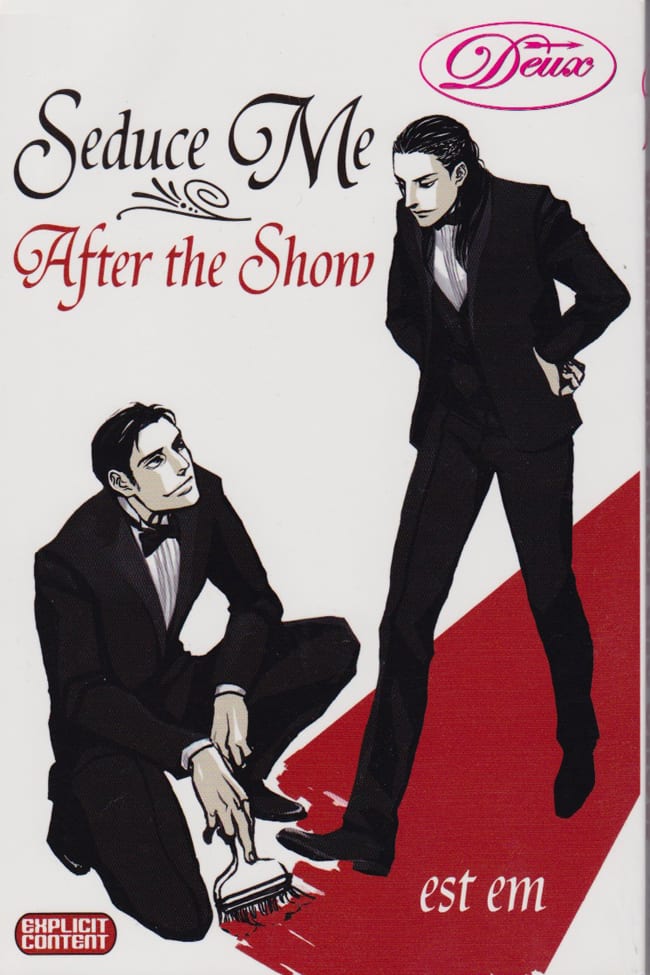

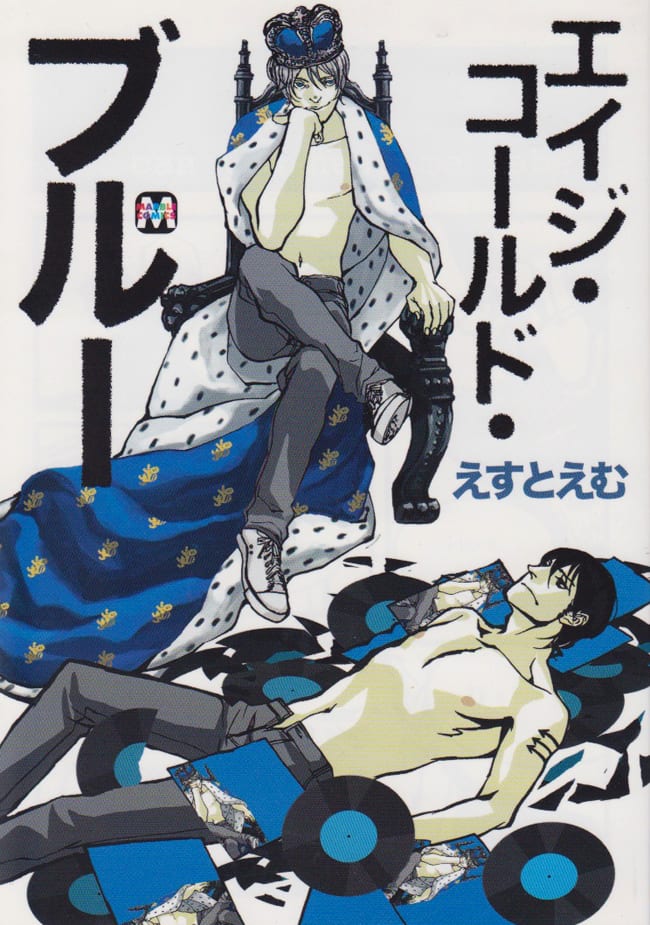

The bulk of comics in the Boys’ Love (BL) genre—manga focusing on sexual relationships between two men (mostly by women for women)—tend to stick to some familiar beaten paths: the salaryman office romance, the younger man vs the older man, student vs teacher. And no matter which beaten path the story treads, the men are generally very stylized and androgynous. But since her debut work Seduce Me After the Show was published in Japan in 2006, artist est em has been clear-cutting her own path, first through the wilderness of more realistic portrayals of men in relationships with each other and then beyond the confines of man-love to the wider manga world with non-BL works like her current series Golondrina and Ippo. Part of a “BL new wave” with fellow BL-but-also-mainstream artists like Fumi Yoshinaga (Ooku) and Asumiko Nakamura (Utsubora), est em has been changing perceptions of BL and proving that good stories range beyond genre boundaries.

The bulk of comics in the Boys’ Love (BL) genre—manga focusing on sexual relationships between two men (mostly by women for women)—tend to stick to some familiar beaten paths: the salaryman office romance, the younger man vs the older man, student vs teacher. And no matter which beaten path the story treads, the men are generally very stylized and androgynous. But since her debut work Seduce Me After the Show was published in Japan in 2006, artist est em has been clear-cutting her own path, first through the wilderness of more realistic portrayals of men in relationships with each other and then beyond the confines of man-love to the wider manga world with non-BL works like her current series Golondrina and Ippo. Part of a “BL new wave” with fellow BL-but-also-mainstream artists like Fumi Yoshinaga (Ooku) and Asumiko Nakamura (Utsubora), est em has been changing perceptions of BL and proving that good stories range beyond genre boundaries.

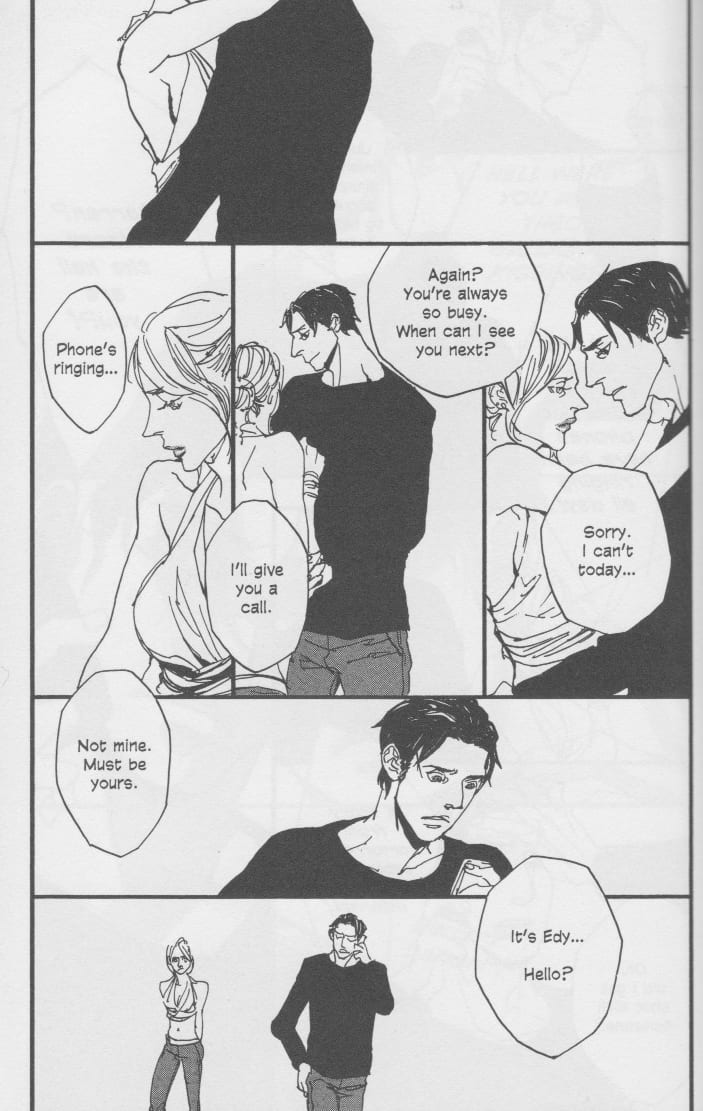

Regardless of the genre she works in, however, est em’s focus never strays from her characters and their relationships with each other. Her sparse panels, frequently lacking any sort of background at all, ensure that readers are paying attention first and foremost to the people populating her stories. And she is merciless with those people, exploring such heavy topics as death and aging with a gentle ruthlessness, as in stories like “En el parque” (Tableau No. 20). But she does not lack a sense of humor. She takes on the silliest-seeming of all possible BL topics—centaurs—in not one, but two books (Equus and Hatarake Kentauros!), making centaurs strangely relatable. And erotic.

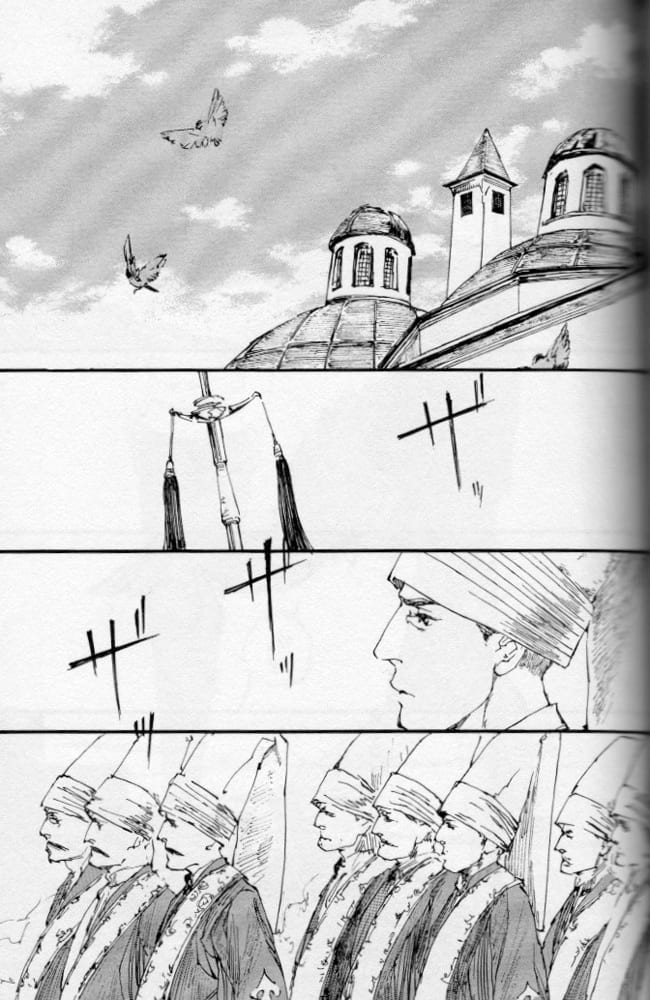

Her men (and horse men) are realistically sexy. They have body hair, unlike the smooth-chested legions populating the majority of BL manga. They are, as manga critic Deb Aoki noted, “men I’d actually like to fuck”. The influence of film is obvious in her panel layouts—so often wordless—letting the art tell the story. She is always looking outside the manga tradition for inspiration, and looking outside Japan for her stories. Her characters live in Turkey, England, Spain, France, the United States. They carry their own cultural baggage, which shapes the way the story plays out. est em is an artist whose curiosity can’t be contained by national borders.

Her most recent work published in English is Tableau No. 20. (Full disclosure: I translated it.) In advance of her visit to the Toronto Comic Arts Festival (May 9–11), I got the chance to talk with her in Tokyo, along with fellow manga artist, Chika Ishikawa, est em’s longtime friend and author of the series Koban! and Metro. After arriving at a Shinjuku restaurant, we chatted about food and what to order before getting down to business.

est em: Go ahead, ask me some stuff.

Chika Ishikawa: I want to do the asking!

Jocelyne Allen: You have questions you want to ask Em?!

ee: Chika, Jocelyne’s Canadian, she’s from Canada. She knows all about manga in North America. We were talking about this festival the other day when we met. She was with some other Canadians, and apparently, there’s this Canadian manga festival. Canada’s great, I wish I could go!

ja: Please, come! Both of you! Come to the festival next year! When you have a new English edition coming out! So this interview is for a site with a more general readership, and I’m sure some readers aren’t familiar with your work. The last time we spoke, we talked more about BL for a BL readership, but since this interview is for a more general readership, I thought we should start at the beginning.

ee: Sounds good.

ja: So first off, where are you from?

ee: Tokyo! I’m from Tokyo.

ja: Really? You’ve always been in Tokyo?

ee: Uh-huh. Born and raised. Although I lived in Kyoto for six years when I was in university.

ja: And at university, you studied art?

ee: I studied manga. They had just started the manga department in Kyoto then, I was part of the second class.

ja: Is that where you met Matt Thorn?

ee: Right, exactly, that’s where I met Matt. Chika’s also one of Matt’s students.

ja: And you made your debut in 2005?

ee: 2006.

ja: 2006. When did you decide to become a manga artist? And why?

ee: Hm, why, I wonder? Obviously, I liked drawing manga, as one means of expression. I liked drawing, I liked a lot of different things. But manga was my favourite, because I could do everything myself. When I was in elementary school, I used to write theatre scripts and make picture books, but what most people will read is manga and you can produce the whole thing yourself. I was really into that, so I figured yeah, manga is for me.

ja: That’s a good point. Do you have any assistants now?

ee: I do.

ja: Oh, you do?

ee: I could do it all myself, but I have deadlines. But creating and drawing the story, I do all that myself.

ja: What does your assistant do?

ee: My assistant does things like screen tone and erasing lines.

ja: Oh, so all the annoying bits.

ee: Exactly! All the annoying bits! I leave all the annoying work to my assistant. (Laughs) That’s really terrible! And people I don’t know are going to be reading this! Ooh, Japanese manga artists pass off all the boring work.

ja: Okay, I’ll just cut that part. [Sorry, est em! I did not cut this part!]

ee: Anyway, I do use an assistant. For backgrounds lately. I have her draw the backgrounds and the adornments on the bullfighter costumes based on photos.

ja: That’s amazing, you get right down to the details.

ee: Yes, they’re very important. And happily, I have a woman I went to high school with working as my assistant. We went to an art high school, so she’s very good with that sort of thing.

ja: So it’s easy for you to work together then?

ee: Yes, we work really well together.

ja: That’s great. …So why the pen name “est em”?

ee: (Laughs) Well, I came up from Boys’ Love, so I was against using my real name, and there’s actually another manga artist named Maki Sato. The kanji’s different, of course, it’s spelled differently.

ja: Sure, but the pronunciation is the same.

ee: The pronunciation’s the same, and both Sato and Maki are incredibly common names, so I figured my real name wouldn’t have any real impact. And I was playing around a little when I made my BL debut, I thought est em worked somehow.

ci: I said she should use “Sugar Roll”.

ee: “Sato” is “sugar” and “Maki” is “roll”, right?

ja: (laughs) I love it!

ee: Sugar Roll.

ja: So I’d be calling you “Roll” now.

ee: Yeah, “Roll”.

ja: I can’t even imagine! Roll, tell me about your career!

(Everyone laughs)

ee: And on the phone, “Yes, this is Roll.” And people would be like, excuse me? Although I guess Americans wouldn’t be able to get my pronunciation there. (Laughs)

ja: When you say “est em” in English, though, the joke is...

ee: It doesn’t come across. I thought it might be a good pen name for being published overseas.

ci: You don’t say “est em”?

ja: Well, “SM” maybe.

ee: But the conjunction.

ja: Right, right. We don’t say “est em” like that. We say “S and M”.

ci: M and M?

(All laugh)

ee: Nothing would happen.

ci: They’d both just be—

ee: They’d both just be sitting there waiting.

(All laugh)

ee: Anyway, impact’s also incredibly important, after all. It’s something you hear once and you don’t forget.

ja: It’s true when you hear “est em”...

ee: In the beginning, of course, you have that question mark. The second time around though... And in French, “est” means “east”. So I come from Tokyo, and they say that Japan is the Far East, so well, there’s the meaning that I came from the most eastern place.

ja: It’s a name with a lot of different meanings.

ee: In Spanish, it’s just the sound, but “esto” [est em’s name in Japanese is “esto emu”] sounds like the word “this”. So my name ends up meaning “this is”. It has the sound of “this is” too. There’s a bunch of different meanings you can find.

ja: You really like wordplay, don’t you? You can see this in your work. For instance, the title of your book Kono Tabi Wa, it has two different meanings.

ee: Definitely. “This time” and er, like a journey or something.

ja: Or occasion.

ee: (Laughs) There are a lot of meanings. So that’s how my pen name happened.

ja: Onto to the next question.

ee: Okay!

ja: Personally, I feel like your style has changed since your debut.

ee: At the time of my debut, my main priority was drawing the things that I could draw or that I wanted to draw, in terms of settings, and music and things. But I put what I wanted to do first. Now I’m a little more aware of entertaining readers, balancing what I want with what people want to read.

ja: The way you tell stories, the details, the art, the content, do you think you’ve changed art-wise?

ee: I don’t know… Hmm.

ja: When I read Kuslar, one of your recent works, what really made an impression on me was how your lines had gotten looser. I felt like your lines have been getting looser and looser.

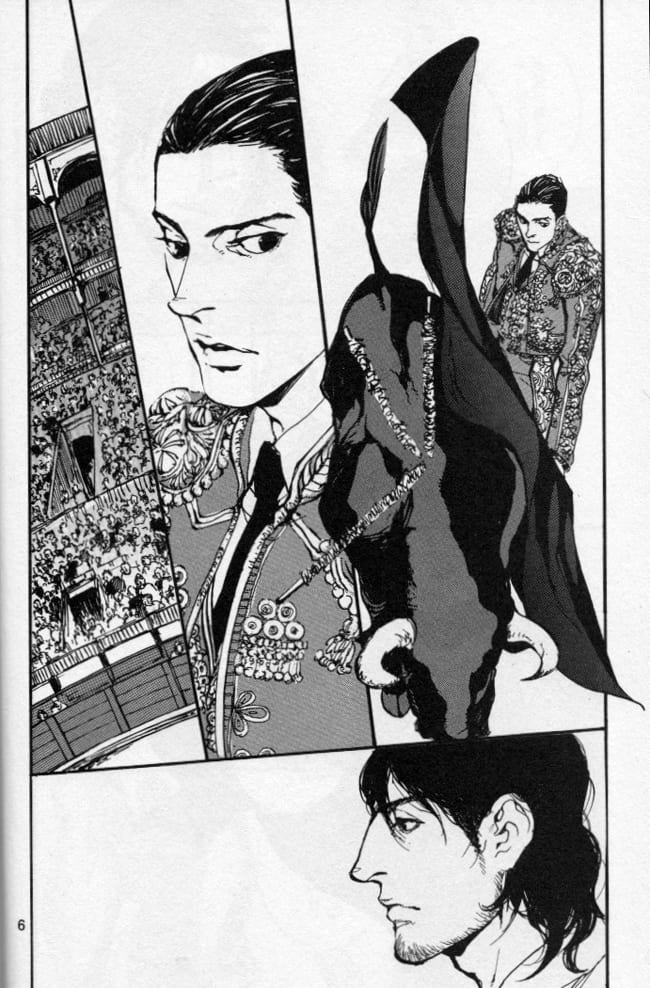

ee: I think my experience doing work for women’s magazines—Of course, Boys’ Love is for women, but work for women’s magazines depicting women is a big part of it. They want a softer line. And for Boys’ Love too, they prefer a softer line. At first, I drew with a very hard line. I drew like that deliberately, but of course, I did some things after talking with my editor about the line, about a bunch of things, like what line would feel right for which person. But for lines like the ones in Kuslar, I’m not sure I actually managed to put them together well. What I really wanted to do, though, are slightly wild lines, rough lines like in Golondrina, the bullfighting manga I’m doing now.

ja: There’s definitely a rough feel in Golondrina.

ee: I think I’m still changing little by little even now, depending on the piece.

ja: Deliberately?

ee: Mm hmm.

ja: So you decide to change your line.

ee: Well, with a seinen manga, readers can handle a rougher line. With women’s manga, that rougher line always ends up seen as a dirty line. So you try and do as clean a line as possible.

ja: Your backgrounds also tend towards the very minimal.

ee: That’s true. (We laugh) The thing is sometimes, I don’t have time. (Laughs) Have you read my debut, Seduce Me After the Show?

ja: I have.

ee: When I was doing Seduce Me After the Show, when I was working on that book, it was terrible. I drew almost 160 pages in two months, in about two months.

ja: Wow!

ee: So I had absolutely no time. My editor ended up coming to the university to get the manga and stood behind me, waiting for the manuscript.

ja: Really?

ee: I’m was working on it with my friends, and I had actually done drafts for all the backgrounds, so we were just erasing them all. (Laughs) And the whole time my friends are all, are you sure we should erase this? Are you sure we can erase this? And I was all, I can’t finish it. Erase it. But of course, there were places where I didn’t draw any backgrounds deliberately, so the end result was a lot of places with nothing. (We laugh.) There was a car here, wasn’t there? There was, yup, there was. In the date scene in “Seduce Me After the Show”, everyone says, there was a car here.

ci: Wow! Really?

ee: And there was a car. There was. I guess I didn’t fool anyone.

ci: So your style hasn’t changed from back when you debuted.

ee: My deadline panic style?

ja: Your deadline panic style! (Lots of laughing)

ee: Always pushing up against my deadlines (laughs), I never miss them, but I get close.

ci: Reeeaaaal close.

ee: Is there anything else about the style I do manga in maybe? Some things I draw thinking about what my editor says, I look at a bunch of different possibilities. So it’s pretty different each time.

ja: Right. But there are still commonalities, although your style is different from book to book. I suppose the main change now is that you’re trying to draw more of what your readers want to read.

ee: Right. Naturally, I’m happiest when what I want to draw matches up with what readers want to read. I still don’t go one hundred percent either way, I try to find that midpoint the best I can.

ja: So with Golondrina now, why did you decide to do this story? Is it a story readers want to read, or one that you want to do?

ee: This manga is for me. (Laughs) I’m drawing it pretty much for myself. But even so, there have been times I’ve really struggled with it. When I try to make it interesting, to make it entertaining, I always worry that I’m drifting away from the bullfighting I want to draw. The thing I’m really conscious of when I’m drawing manga is why I’m a manga artist. Obviously, I want to communicate to other people things that I know and things that move me, but I also want to reach out to those worlds myself. So there’s also part of me that wants to go with a certain setting. By depicting that world in my art, I end up thinking more deeply about it and knowing it more deeply. And I wanted to do something with bullfighting. I had to do bullfighting. I wanted to draw it and I kept thinking about drawing bullfighting and about bullfighting itself. Because there are so many things I don’t know about it. (We all laugh.) Naturally, in terms of simple knowledge, there are a lot of things I don’t know, but in terms of feelings, I wanted to do something that tries to understand, that imagines what that person standing there is thinking, what they can see by putting a protagonist in this place that I have no way of understanding.

ja: So you’re expanding your own viewpoint?

ee: Exactly. With bullfighting, I’ve seen some really impressive moments in the past, and I really wanted to draw those scenes. So I started with wanting to understand the feeling behind those moments. Obviously, I’ve taken up bullfighting in Boys’ Love too. The series I’m drawing now is, well... Before, the story was a little abstract, it was the idea, the idea of bullfighting, and now, I’m going deeper into that world.

ja: So how did it end up serialized in IKKI?

ee: Kind of in the back door which is maybe a cheat, but when I was drawing for this women’s magazine Feel Young, I was asked what I’ve always wanted to draw, something I’ve wanted to draw that wouldn’t work for a women’s magazine, and I said I wanted to do bullfighting. (Laughs) And there was this moment of what are we supposed to do with that. But of course, because I knew I wouldn’t be allowed to draw this, I tried to find things I could do for the magazine. But I was always saying to my editors the thing I wanted to do the most was bullfighting.

ja: Like you were asking someone to please let you do this?

ee: I kept saying I know I can’t do it here, I know I can’t do it for this magazine, but what I really want to do one of these days is bullfighting. And then by chance, my editor then knew my editor now, and she mentioned that one of her manga artists was saying she wanted to draw a bullfighting manga, and he said, okay, then maybe we should meet. And obviously, this didn’t mean I immediately started drawing. He just listened to what I had to say. I showed him what I wanted to do, like this is what I am thinking, how about it? And he said it sounded interested and how about we give it a go, and that’s how it started.

ja: IKKI’s fairly mainstream.

ee: Not at all. It’s really less than alternative.

ja: But it’s more mainstream than BL magazines.

ee: It is. In the sense that it’s a seinen magazine. For a more general audience.

ja: Right, it’s a more general audience magazine. Is that the direction you were wanting to go in?

ee: I never sought out BL. And you get really tired of only drawing BL. (Laughs) I get so that I don’t even know what I’m supposed to be doing. Just dealing with the romance is exhausting.

ja: And you’re dealing with the same topic with josei too.

ee: Right. Love ends up part of the story for josei magazines too. So I really wanted to draw something that wasn’t that.

ja: I can understand that.

ee: But that’s what I got the chance to do. Originally, before I made my debut in Boys’ Love, I wanted to study in France and do BD [bande dessinée]. I had this idea that I wanted to get to know the world of BD. Because the things you can express with BD are different from in Japan, you know, it’s a very different world. So I wanted to get to know that more. Then I made my debut and I ended up getting a lot of work. And you know, I talked to some French artists and they said I should be telling my stories in Japanese. The idea was if I started working as an artist, I could branch out into other things from there. I was also faced with the hurdle of learning French if I was intent on doing BD, and that seemed like a waste as an artist. So I started thinking, well, I guess there’s probably something I can do in Japan.

ja: Hooray! (We laugh) As one of your readers, I just want to say thank you. (more laughing)

ee: I do think I was right about that decision. The possibilities in the world of Japanese manga are huge, there are so many things. You’re free. I have more freedom that I thought I would. I thought I’d be more constrained. Of course, I still have battles to fight.

ja: Looking in from the outside, it seems like a pretty constrained world.

ee: It is.

ci: It totally is.

ee: But that’s probably the same no matter where you are, the conditions are just different. There’s no such thing as complete freedom, is there?

ja: Well, maybe if you’re rich. That’s a whole different story.

ee: It is. When I was younger, I guess, when I wasn’t sure about a lot of things about myself, I would meet young artists from overseas and we would talk, and you know, everyone had their own work, their own dilemmas. But they had something else that they wanted to express, and they’re doing that too. I ended up really feeling like no matter where you are, you still have conditions imposed on you. You’re stuck with that. And I’ve been given this arena of my own, so I’m working hard in that arena.

ja: You’ve really put a lot of work in, too.

ee: But my position on drawing, I think we talked about this before too.

ja: We did. I think we talked about something along these lines before.

ee: I’m interviewed a fair bit for Japanese magazines, like manga or culture magazines, but my answers haven’t really changed from six years ago, so I feel like it’s kind of annoying, like it’s weird that now and then are the same.

ja: You’re asked the same things?

ee: And I repeat the same answers.

ja: So, your career… I was wondering what kind of reaction you’ve gotten from readers with Golondrina now.

ee: We haven’t gotten that huge of a reaction yet. But from what I can see, the idea of bullfighting, it’s not really that familiar in Japan. If you do see bullfighting here, it’s the running of the bulls on a variety show or some kind of video thing with bulls, and that’s all Japanese people know. It happens in a Western cultural sphere and they don’t know what kind of background there is or what the rules are; a lot of people don’t even know the bull dies. And I can see how people would be surprised by this. Then there’s the fact that the protagonist is a girl, so people are seriously interested in whether there are female bullfighters.

ja: Are there?

ee: There are, actually. Right now, only one of the women active is a top bullfighter, but in the lower ranks, there are several women learning, novilleros, the fighters who only take on young bulls. They’re actually being accepted. There aren’t very many people trying to become a bullfighter, so naturally, there aren’t very many women doing it. But it’s not that this world is taboo for women. And not because this is the modern era. Women were forbidden to be a part of it during the Franco regime, but before the Franco era, in the 1930s, there were female bullfighters.

ja: Oh, really? I had no idea.

ee: Me too. I learned about all this after doing a bunch of research.

ja: So you go to the library a lot?

ee: I do. There are no books in Japan, so I ask people who know about bullfighting in Spain and things like that. Very few books on bullfighting have actually been translated in Japan, and there are only a few books written by Japanese people.

ja: So you look things up in Spanish?

ee: I do my best to read the books, but it’s so much work my head practically catches fire. So for the most part, I go to Spain and talk to people, or talk to people in Japan who know about bullfighting, or I connect with the things I’ve seen and get my information that way. An incredible amount’s been written about bullfighting in Spain, and well, my Spanish is about as good as a 10-year-old. (laughs)

ja: But isn’t that good enough?

ee: To read books, it’s still not enough. I have to study more.

ja: But you go to Spain every year, right?

ee: Yes, I go every year.

ja: For how long?

ee: About a month. A minimum of one month. But I’ve gone for three months before, and I’ve gone for a month and a half. Lately, it’s been a month.

ja: So how long are you planning to go for next?

ee: I’m planning to go in May or June next year. But it’ll be a little short. I can’t really stay long because of work.

ja: Work always gets in the way.

ee: It does! (laughs) But if I don’t work, you all don’t get any manga, you know.

ja: So why Spain?

ee: At first, I was interested in flamenco. When I was a university student, I used to watch Antonio Gedas’s films. Films like Blood Wedding and Carmen. I watched all those films with famous flamenco dancers in them. And I got really into the world of flamenco. Right around that time, there was this flamenco dance troupe who came regularly to Japan, and they did this performance. These famous flamenco dancers did some contemporary stuff, and performed things like Salome. They did a mix of dance genres using flamenco, which made it a very easy point of entry. So I was first interested in flamenco, and then I got interested in Spanish culture. What got me interested in bullfighting was, well, there’s this song that’s famous in Japan, “Torero”. It’s about this stupid bullfighter. And my friends and I ended up talking about that bullfighter. Which turned into talking about maybe trying to draw that in a manga. When I went to draw it, though, I couldn’t just draw a stylized version of it, so I had to do the research. I was shocked by so many things in the books I read. I knew that bullfighters die; I just didn’t think they were killed even now. I mean, it’s the twenty-first century. So I realized there was still this culture where bulls were actually killed. It wasn’t just for festivals, it wasn’t just some kind of performance. I remember being really surprised at the fact that this was something serious that really happened.

ja: It would be surprising.

ee: It was, it was surprising. And in Europe, Europe where they are so particular about animal rights. I was surprised this culture still existed in Europe. There was also the question of why and how incredible it was. There was the beauty of it and a definite theoretical, maybe not theoretical, but there was a part of me that thought this was wrong. I like animals too and I love cows. But a part of me was really attracted to it. I was really attracted to the fact that this kind of thing native to Spain, that this culture was still there. And that contrast of bullfighting, the contrast between life and death, the contrast between light and dark, I was really, really attracted to this dichotomy, this black and white, and I figured I should actually go and watch it to start. (laughs) So I went ahead and read a bunch of books, and I wrote “Red Blinds the Foolish”. And the idea of bullfighting, there are all these dances danced, books written, poems, songs, these things that build up the image of the bullfighter, and that’s what I drew then, but by the third part, between the second and third parts, I went and actually saw bullfighting. Which made me think about a lot of things, and this was when I drew the third part. That’s when I started thinking that I wanted to draw the story of bullfighting properly, which led to Golondrina now.

ja: So the first time you went to Spain was?

ee: 2007.

ja: And you’ve been going every year since then?

ee: Yes, right.

ja: Obviously, you have a fair bit of research to do in Spain, but are there other things you want to do?

ee: I go to the beach, see my friends, drink. I do a lot of things. Although, I guess I do end up going out drinking a lot.

ja: So can you cook Spanish food?

ee: Oh, of course, a few things.

ci: Her cooking is super delicious.

ja: Oh, really?

ee: Well, this patatas dish, you cut some potatoes, fry some eggs, you do this thick egg thing. It’s delicious. I can make that.

ja: Oh, wow.

ee: I can do paella too.

ja: Soooo, if you were to compare Spanish and Japanese men, which are better? (Lots of laughing) I mean, you’re a BL author!

ee: I am. That’s true. I think they are, well, good points and bad points for both. Seriously. It’s more casual in Spain, but I don’t know how to put it. Obviously, since I’ve never dated a Spanish guy, I don’t know, but from what I hear, they clearly have that national character, and it’s not like what they’re looking for is that love thing. And some people are uptight about this. Coming from a Japanese sensibility.

ja: Right, I see. That makes sense.

ee: But I think there are a ton of passionate people. It’s the opposite of Japan. But well, I think they’re very gentle, kind. Almost an indecisiveness. It’s the same difference, really. There’s no perfect man in any world.

ja: There’s not, no, there isn’t. No matter where you go.

ee: As we all know.

ci: Not even in Canada, huh?

ja: As I know only too well!

ee: Also, I guess, Spanish culture, well, for instance, a lot of people love football, soccer, the architecture. Of course, Gaudí is famous, but I really love the areas in the south where Islamic architecture is mixed in. I’m pretty interested in Islamic culture, and I’m very attracted to this kind of cultural exchange. It’s a country with this contrast of two cultures, and naturally, a lot of things are brought into the country.

ja: But in Japan as well, you have different cultures, don’t you? Like the Ainu, you have that sort of thing.

ee: They didn’t get incorporated really, on Honshu or anything. It’s that mixing of cultures that really interests me. Like in Turkey, Istanbul is this Islamic city while still being this city of exchange. That’s really fascinating to me.

ja: Are there any stories you want to do on Turkey in the future?

ee: Hmm, what would I like to do. I’ve only been to Turkey five times. I hadn’t really thought I wanted to draw the past before my third book, but it is fairly interesting to look at the city as it is now, and some things about it are hard for Japanese people to get in terms of the idea of the place.

ja: I think it’s really fascinating. I mean, especially, when I read your recent work, you have these historical stories, but you’ve also got contemporary stories in there too.

ee: Right. I originally started out wanting to draw the contemporary stories. I wanted to draw Turkish cities as they are now, but when I talked with my editors, they were all, if you’re going to draw Turkey, you have to draw the past too or else people won’t really get it. That’s why the old city’s in there. When I first started drawing, I had absolutely no ideas, but I was asked to draw something to do with Turkey, so I said, sure, sure, yes, I’ll try to do something. I’ll try and draw something.

ja: But are you thinking you’d like to draw more about Spain? Although I know you’re right in the middle of Golondrina, so you’ve been drawing Spain for a while now.

ee: There are just a lot of things I want to draw, I want to draw everything I’m interested in, not just Spain. That’s one thing I think that’s not so good. I just want to draw what I’m interested in, and I never think about things I should be drawing.

ja: But that passion is communicated to your readers.

ee: I hope it ends up being a doorway. For instance, whether it’s music that gets me interested in a country, or whatever it is that gets me interested, I end up wanting to know about that country in manga. If it can be an entry point, then it’s fun for me.

ja: You often use foreign countries as your settings.

ee: I guess I do. I think I just like things I don’t know about.

ja: I’ve gotten that impression from you.

ee: I think it’s because I have this really strong desire to reach out to things I don’t know, things I haven’t done, experiences I haven’t had. Of course, I still know nothing about Japan either, and in the future, I’d definitely like to look more towards Japan. But you can’t travel abroad if you don’t have the stamina, if it’s not when you’re young and you have the stamina.

ja: Naturally. So you’ll be taking up Japan later? (laughs)

ee: There are so many other people doing such great work about Japan. I’m actually satisfied reading their work. But when I want something about somewhere overseas, if no one’s writing that work, then…

ja: Have you had the chance to have contact with your fans overseas?

ee: I have had a fair bit of contact with them, actually. With Americans, in France, and recently, I went to Ukraine this year.

ja: Oh wow.

ee: I happened to mention on Twitter that I was going to Ukraine, and this Ukrainian fan reached out to me, this Ukrainian woman who can speak Japanese. She lives in Japan, but is from Ukraine. She was just planning to go back, so she said you know, if you’d like, I can show you around. I was like, oh great, I’m so lucky. But she ended up not being able to come. Anyway, I was supposed to go to this town on the coast of the Black Sea, and she happened to be from exactly that place, so I was looking forward to it. But she said she’d introduce me to some friends of hers since she couldn’t come. So she did, and they showed me around the town. We had tea and things.

ja: That sounds like fun.

ee: It was. And of course, they really loved manga. So we talked a lot about manga and things. It was a ton of fun. And when we were talking about Ukraine, they said I have fans in Russia too, and their Russian friends really wanted to meet me, they said hi! And I was all! (laughs)

ci: Wow!

ja: That really is wow.

ci: You’re just drawing manga, and all these people outside of Japan are reading you.

ee: Which is why I really want to do things like this. I can’t meet everyone everywhere, but my manga can do it for me. This kind of connecting, people connecting with people, and obviously not just with me, those girls were connecting with each other too. And I think it’s amazing manga can bridge that gap. I was so happy to meet those Ukrainians. I’m honestly just glad to have anyone reach out to me.

ja: I heard that you were looking to increase your readership overseas.

ee: I am. There’s a sort of, well, conservativeness in Japan when it comes to translations. But once we get into an era where you have electronic versions translated into English one after another after another—although, obviously, that would be really hard on the translators…

ja: That would be such fun work! (Everyone laughs.)

ee: And with a solid readership, we can pay solid margins as the number of readers increases. I think it’d be great if a system like this could be set up. But that’s a serious amount of work, doing the translations and everything. And I know that rates have really gone down compared with in the past, right?

ja: That’s true.

ee: You have all these amateurs coming up, and so many scanlations and things like that, so you really need people at the publisher level to be paying a good price to serious professional translators and producing works of real quality.

ja: Right. We talked about the bootlegs before too.

ee: We did. Naturally, being read is basically my top priority, but if my manga ends up opening up these girls’ world and they end up wanting to know more, that might lead them to the official book or whatever. In the end, though, I draw because I want people to read me. I can’t say anything against this broader scope. I’d actually say instead that all of this is because there is this potential in manga. It’s just that price and speed are serious issues. So you can’t just denounce the pirating, you have to look at how you do manga, how you change things, how to actually get it to readers.

ja: Right, exactly. As long as there are no other options, the bootleg versions are going to keep coming out.

ee: Because while there are fewer and fewer people reading manga in Japan, there are so many possibilities out there in the world.

ja: Is that why you decided to publish your work digitally?

ee: Right now, there are digital versions of all my published work. But the price for the digital versions, it’s basically the same as the paper versions.

ja: So for instance, this year, I’m pretty sure it was this year, Apartments of Calle Feliz and Working Kentauros—

ee: The English versions.

ja: Right. But they were only released digitally. There aren’t any plans to release the physical books?

ee: No, there’s no plan to release them as print books. But I guess that’s natural overseas; the number of bookstores is completely different, right?

ja: So, so different. Very different.

ee: If you live in a big city, of course, you have the chance to go to a bunch of bookstores, but in a small town, even if there is a bookstore, they might not have Japanese manga or things like that. And I think for kids like that, who get their information online, well, it has to be digital. So I don’t feel any particular need for paper.

ja: It seems like other Japanese manga artists have been reluctant to release digital versions of their work.

ee: I think there’s some more conservative attitudes there. But I mean, this is a culture that has come up with this incredible focus on paper, and you know, from this cultural aspect, manga itself has developed as this method of expression with a serious awareness of the pages being turned. So it’s very much about how it looks when you open the book, when you flip through the pages, the way it plays. Manga artists really put a lot of thought into the production. I really think everyone’s terrified of that turning page disappearing. I think it’s not digital itself that’s the problem, it’s this turning of the pages.

ja: You don’t have a problem with that yourself?

ee: The production, the page turning, they’re also really important to me. And the beauty of black and white. That’s a major premise in printing Japanese manga, it’s a culture that’s placed a lot of emphasis on black and white. It’s really honed the ways to show things in black and white, so if you start shouting about how this culture’s not necessary, you’re knocking everyone’s feet out from under them. If things are in color, that’s inevitably a new way of doing things. People have to accept something totally different from the foundation they’ve known, it’s not just going to happen overnight. A lot of people are going to be negative about things like this.

ja: I guess so. But my thinking is that the number of scanlations would drop if authors were putting out ebooks.

ee: That’s where speed comes in. When you hear from fans overseas, the biggest thing is that they want to read the stories when they come out.

ja: Right, exactly!

ee: Of course they do. I mean, Japanese film fans, when you ask why they watch pirated versions, it’s because the Japanese release is just not happening. You can see why people go with the downloads. But really, with translation, you need someone with that sense of speed.

ja: Speed really is the issue, isn’t it? Which is why Viz started to release the English version of Shonen Alpha day and date with the Japanese version.

ee: That’s the key. And with purely informative magazines and things like that, you can just go ahead and translate things as is, but with manga, you have take into consideration the cultural aspects. Once you start thinking about what kinds of things are behind the words, you’re not necessarily going as fast as you’d like.

ja: But if you get the manga in advance, like the manuscript or something, you can work it so that they’re published at the same time. It’s possible.

ee: With the Japanese publishing schedule, though, that ends up being incredibly tight.

ja: It does.

ee: And that’s it, isn’t it? That’s the problem. The manga artists have a tight schedule, the publishers have an incredibly tight schedule, and it just gets passed down the line. We have to hurry, we just have to hurry to get it out, or the customer! We say it’s because it’s just for Japan, and we need to think of another strategy if we’re going to do anything for the outside world. And I do think there are a lot of people working in that direction now. Like with ebooks, a lot of people are trying to figure it out and doing experiments. I think it’s still going to take some time for these things to become the mainstream, though. But I suppose, from the perspective of the reader and of the writer, a lot of people out there are ready to reject anything electronic. And me personally, there’s a part of me that feels like maybe it’s better if people pick up the paper version.

ja: I’m the same way. Rather than digital.

ee: You just want to have the book, right?

ja: You do!

ee: I think there’s that. That physical object. We all have our obsessions, I guess.

ja: It’s like the real thing. You get that book published on paper, you take the cover off, you check what’s on the back, all that stuff.

ee: The extras, right?

ja: Right! I really love things like that.

ee: It’s different. The book itself is a piece of art on its own. So many people have put so much effort into it, thinking and thinking about the binding, what kind of paper to use, what kind of font to use, how everything would look best.

ja: Exactly.

ee: So maybe the future, it’s not exactly reverse evolution here, but books used to be the domain of rich people, right? The general public couldn’t read, and rich people were able to get the manuscripts, talk to the book binders, and put the book together in these luxurious bindings. We had that culture before, so maybe this is coming back to that.

ja: There’s that tendency now.

ee: And there’s that difference in how you look at it, if you see books as works of art or as information. It’s basically about figuring out where you stand and accepting yourself, so I really think dismissing it all out of hand is totally ridiculous, for scanlations and for ebooks. It’s difficult. I mean, you look at how we came up with manga, and it’s usually the local community centre or something. Manga were everywhere for us to read, and it’s not like we bought them all ourselves. They were in the waiting room at the doctor, or at the hairdresser, or at the local kids’ centre. There were so many manga we could read for free.

The waiter brings us more food, and we devote our attention to that for a while.

ee: Is it hard to translate the jokes?

ja: What?

ee: Japanese jokes are tough, right? I guess the opposite is obviously true too, English jokes in Japanese.

ci: Totally impossible. The things Japanese police say or train station attendants, it’d be so hard.

ee: It would be hard.

ja: It is hard.

ci: Would they get it overseas?

ee: It wouldn’t work overseas. But I guess everyone’s into all these different things so.

We pause to eat, when suddenly:

ci: Full House, Full House!

ja: Full House? Seriously?

ee: Seriously, she asks if you’re serious!

ci: Why?!

ee: Japanese people like Full House, you know.

ci: Full House is the manual for my life!

ja: Only the worst shows comes to Japan. It’s always the most terrible stuff.

ci: Full House is terrible?!

ja: Honestly, when I lived in Japan, I would always just be incredulous. This got translated? Especially the stuff on NHK, it was always stuff like Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

ee: What? What about Alf?

ci: Which is worse, Alf or Full House?

ja: Hmm, Full House. (We all crack up.)

ee: We should talk seriously now.

ja: Yes, let’s get serious.

ee: OK.

ja: Very serious.

ee: Serious, serious.

ja: Right now.

ee: Ha ha! That look is great! (laughs) What happened to your face?

ja: No, I was just trying to do my serious face. Okay, this is my last question. Which of your works do you like the best?

ee: The one I like best is the one I’m working on now, Golondrina.

ja: Oh, really? Why is that?

ee: I’ve wanted to do it for so long. And I think having the freedom to draw it without limitations is a factor too. Up to now, I’ve always had to put in some kind of romance. And it’s not that I don’t want to draw these love scenes, but of course that feeling like you can’t do anything else is huge. This is going back a bit, but in my third or fourth year as a manga artist, I was really stuck on if I could draw something better than my first manga.

ja: Really?

ee: I honestly liked the three books I did, Seduce Me After the Show, Age Called Blue, and Red Blinds the Foolish, and I personally felt like I had done a really great job with them. I drew them how I wanted to, and I think I was really able to communicate my world view in them. So there was the fact that I really did like these three books, and I really got stuck on the idea that the me at that time couldn’t draw anything better than those three books. Now with Golondrina, I’ve found a me whose drawing with much more focus than back then. Which is why I guess I like what I’m doing now the best.

ja: You don’t always like your current project best?

ee: I don’t, naturally. And I really struggled with this for a long time. But at the end of the day, those older works are a part of my history, and rather than being more together than those works were, I really feel like I was able to draw this because I’ve grown. The thing is, I’ve really struggled while writing this. There’s what the readers want and what I want to draw, and then there’s how to approach bullfighting, which I knew nothing about. I’m always struggling with all this… It’s really tough. When I was drawing soccer, I didn’t have to go out of my way explaining the rules of soccer, like “you want to get the ball in the goal over there.”

ja: Right, there’s no need.

ee: But with bullfighting, I have to explain from square one just what is going on when something happens.

ja: We don’t know otherwise.

ee: Exactly, it’s hard.

ja: It must be. But, well, I think just creating something is hard in and of itself.

ci: Making a one from zero, and making two from one, they’re completely different levels of hard.

ee: Well, we’re not starting from zero… supposedly?

ja: So why not from zero?

ee: There are already a lot of elements there. Putting those pieces together, building these 0.01s up to get to one is our job. We definitely don’t start at zero. We’re putting together these super tiny pieces, like 0.01 or 0.02. It’s definitely not zero, but the work is directionless. (laughs) It’s a tough job.

ja: But you’ve got your editor, right? Japanese and American editors are totally different too..

ee: Yeah, yeah, absolutely.

ja: With American comics, the artist draws what she wants to draw, and then the publisher decides whether she’s going to publish it or not and that’s that.

ci: So they don’t really have any say about the story?

ja: Not really, no.

ee: It’s just Japan. Where editors have a say.

ci: What?

ee: In Europe too, once you bring the project in and get the okay, it’s basically hands-off after that.

ci: That sounds great!

ee: It does sound great, right? That’s what I thought when I was at university.

ci: What? That was ten years ago.

ja: You don’t think so now?

ee: Well, both systems have good and bad points, right?

ja: That’s definitely true.

ee: When I talk with Europeans, of course, some people say the Japanese system is great. Say, for example, this is the thing you want to communicate. There’s no way your editor’s going to say a flat no to you communicating that thing. But they are going to say something like if you want to communicate this thing, you should use this kind of wording here. And doing this, they change this thing that maybe only ten people would get into something a hundred people can get, which is kind of amazing.

ci: That’s true, but then everyone ends up saying things the same way as their editors.

ee: Obviously, there are good and bad editors, but good editors, they have this way… they clarify what the author is trying to say, they make it easier to understand.

ci: That’s because they get to see the seamy underbelly!

ee: The seamy underbelly! (laughs) But there are a lot of different stories out there. And there are good and bad editors. Just like authors have different abilities, so do editors.

ci: You’re totally right. We shouldn’t just say that all editors are like this or like that.

ee: It’s that dialogue. It’s wanting to create something through this dialogue. What I think is interesting about Japan is the way you share this vision about the thing you’re going to create. I mean, overseas, the editor is the editor and the comic artist is the artist; that vision isn’t shared. When it comes down to it, the editor is just there because there’s just this goal of publishing. When you ask why people have been reading Japanese manga all this time, it’s that the editor is the editor, this person who doesn’t draw, but who’s a good advisor. She really shaves it right down to the author’s interior to bring that out, and that’s where we can squeeze in the opinions of regular readers. So they can think about the work from these two directions, these two places of what the artist herself wants to say and what the person engaging with her work is looking for. It really is a lot like the world of movies, and I think that’s the reason a lot of Japanese manga gets picked up in Hollywood. There are a lot of people involved and there’s also a place for the producer. I mean, in Hollywood, you don’t get money to make it if it’s not going to sell, right? The movie passes through so many hands. Someone writes the script, that gets revised a bunch of times to make it even easier to understand and more appealing to the general public.

ja: Right, right. It’s not just one person.

ee: Naturally, I’m not saying anything bad about Hollywood films here. They can definitely move people. If you look at it in terms of markets, with French films, the director wants to shoot it a certain way. For instance, Truffaut would probably would not have even listened to an editor or a producer.

ja: He totally wouldn’t have.

ee: Obviously, there are people who recognize his artistry, but for example, if you showed his work out of the blue to university students or something and said, okay be moved—it’s like this with Godard as well, only select people understand, or rather communicate a universal message through popularization… I guess it’s a kind of required filter in this sort of thing.

ci: But then you have the part where the person you’re trying to engage is lost.

ee: Definitely! Desperately lost.

ci: I mean, some people are going to say they really hate the sort of thing you’re doing.

ee: Of course, you run into serious conflicts.

ci: I mean, with works that lend themselves to popularization right from the start… The bigger the publishing companies get, the more they want work that’s easier to understand. Obviously, there’s the dilemma there too.

ja: I think that’s the same no matter where you go now.

ci: But if you manage to make a good compromise, you can do what you want.

ee: You do make those compromises, you do! But it’s probably still not enough. There’s that line between how much you can take and how much you can push.

ci: Bullfighting.

ee: Bullfighting, right, that’s tough. You can’t popularize that. And obviously, I’m dealing with the life and death of animals, so of course there are going to be people who hate it.

ja: Of course. But that can be said about any work.

ci: There are plenty of manga where people regularly die instead of animals.

ee: They drop like flies in Death Note.

ci: They do even in your average shonen manga.

ee: That’s true.

ja: And if readers are uncomfortable with it, I think that’s just proof that the work is good, that it’s provoked some emotion. The worst is when people don’t have any real reaction at all.

ci: What’s even harder than no reaction is when people are just not interested. That’s the hardest.

ja: Exactly. You want people to have some kind of emotion.

ci: Whether they like it or hate it, that’s true.

ja: Right. Well, I’ll look forward to the English version of Golondrina!

ee: I would like to see it translated. It’s funny. When I was first setting the characters as Spanish people, the names were just too far removed from Japan, so my editor asked if there wasn’t a name I could use that was kind of Japanese. My editor said that “Maria” was still a bit distant, and so we went with “Chika”. Of course, there is no such name in Spanish. Because the word “chica” means girl.

ja: And you turned that into a name.

ee: Right, right, right. I used that as a nickname for my protagonist. Chika is a nickname.

ci: But I thought that was based on me.

ee: It’s not based on you.

ja: Do you do signings and things?

ee: I don’t.

ja: You don’t?

ee: I’m asked to sometimes, but I don’t know, I kind of hate that sort of special guest treatment. “So-and-so sensei!” That’s how they treat you, and it’s just… I think that it would be fine without all the fanfare. I’m basically fine with a casual request.

ci: Being called “sensei” feels kind of awkward.

ee: Exactly! I hate having that seat just for me. I mean, I like sort of shoving myself in there, but I don’t really like having a place set aside for me.

ja: So do you travel a lot? I know you go to Spain every year.

ee: Only Spain. Only Spain and Turkey.

ja: You don’t want to go anywhere else?

ee: Of course I want to go other places, but there’s the bullfighting in Spain every year. My favourite bullfighter fights every year. He grows each year.

ja: So you have to watch him.

ee: Exactly! I met the parent raising him as a bullfighter, I met the person raising him, and I was told to watch him until he was twenty-five, until he was finished. So I figured I better watch until he was twenty-five.

ci: Is he young now?

ee: He was young. He debuted when he was nineteen.

ci: How old is he now?

ee: Twenty-five. He turned twenty-five this year.

ci: So then you have to go next year.

ee: I have to go next year. And he better not do anything reckless again next year, that idiot. He took on six bulls in the biggest bullfighting arena.

ci: At one time?

ee: Normally, no no, one at a time. Six times. Usually, with six bulls, three bullfighters get two bulls each.

ci: That’s reckless!

ee: Only the really famous of famous bullfighters do things like this.

ci: You must be really looking forward to that.

ee: And they do it in the largest bullfighting arena. Four years ago, he made a huge mistake in this largest arena and that was that. It was a total failure. He couldn’t fight the bull properly at all.

ci: What does it mean for a bullfighter to be a total failure?

ee: Not being able to do anything is a total failure.

ja: I thought dying would be the total failure (laughs).

ee: They do die sometimes.

ja: Is that seen as a failure too?

ee: Depending on how things go, they might die in a really bad way, or they might die a legend, totally different. And there’s a value to dying there, so that’s something I’m also very interested in, the terror of the spectators determining that value.

ci: I don’t really like bullfighting myself.

ee: I know. Because the bulls die, right?

ja: I’m with her. Sorry. But it’s fun to read about.

ci: It’s just ow, ow! No matter which side it is, someone’s going to hurt.

ee: Yeah, you’re right. It’s just, I really wanted to know why this took root as this culture. I’ve been watching bullfighting for five years, and I’ve been able to see these tiny changes in the bullfighters; it’s not something that happens there, it’s different from the spectator level.

ci: The fact that the bulls die is of course huge, but it was only from her manga that I was able to see that there’s also other more beautiful things there. Seeing Spain in there, a part of me that wonders if it’s not okay on some level. It’s not like you’re just watching the bull dying.

ee: That’s it. It’s like the sacrifice at a festival back in the old days.

ci: That’s exactly it, right. You need to find that point of compromise within yourself.

ee: You can’t force it. Honestly, there is all this drama with the people who come to watch, and drama with the people who are there somehow.

ja: Okay so finally, the last last.

ee: Okay.

ja: What are your plans from now on?

ee: Well, my current serializations, I have two, excluding the small things. I’m working on two major serializations. I have Golondrina and Ippo, the shoemaker manga, but they’re both at a stage where I can relax a bit. Once the serialization is done and the tankobon come out, I’ll be sort of at a loss for a while.

ja: At a loss? (laughs)

ee: I’ll just wander the world.

ci: Will you go to Canada?

ee: I’d like to go to Canada. But mostly I’d like to wander around South America.