Fish Girl, which has just been released by Clarion Books, but writer/artist David Wiesner is not just any debut graphic novelist. He comes to comics as one of the most acclaimed storytellers of his generation. Wiesner has been awarded the Caldecott Medal three times – one of only two artists to ever do so – for his books Tuesday, The Three Pigs, and Flotsam. He has also received three Caldecott Honors among his mnay other awards. Earlier in his career he illustrated books by Avi, Jane Yolen, Laurence Yep, Allan W. Eckert and others. Wiesner even created an app called Spot which was an interactive exploration of worlds within worlds.

Fish Girl, which has just been released by Clarion Books, but writer/artist David Wiesner is not just any debut graphic novelist. He comes to comics as one of the most acclaimed storytellers of his generation. Wiesner has been awarded the Caldecott Medal three times – one of only two artists to ever do so – for his books Tuesday, The Three Pigs, and Flotsam. He has also received three Caldecott Honors among his mnay other awards. Earlier in his career he illustrated books by Avi, Jane Yolen, Laurence Yep, Allan W. Eckert and others. Wiesner even created an app called Spot which was an interactive exploration of worlds within worlds.

Over the course of his career, Wiesner has cited and paid tribute to comics and many of the artists who influenced him. Jack Kirby was one of the people that Wiesner thanked when he accepted his second Caldecott. The exhibition David Wiesner & The Art of Wordless Storytelling is currently at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art through May and then opens at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in June. The exhibition catalog has just been published by Yale University Press.

Throughout his career Wiesner has been interested in wordless storytelling and so it seems natural in some way that he would eventually create a graphic novel with a character who almost never speaks. He was kind enough to talk about how making a graphic novel was different from making a picture book, the way he works, and how he’s already thinking about making another.

I know that you attended art school. What were you reading and what interested you and inspired you when you were starting out?

Every time I saw an example of wordless storytelling, I had a very strong reaction. The first place I encountered a wordless sequence was in Jim Steranko’s Nick Fury comics. Later I saw the wordless Azrach comics by Moebius. Once I found Lynd Ward’s wordless woodcut novels from the 1930’s, I knew this was a direction I wanted to explore. I did this in my student assignments whenever I got the chance.

By my senior year I knew I wanted to continue with sequential work when I graduated. I didn’t want to go into comics. I didn’t want to be a superhero person and comics weren’t what they later became. While I was there I studied with David Macaulay quite a bit and he introduced me to the world of picture books, which quite honestly I wasn’t all that familiar with. I didn’t grow up reading a lot of the classic stuff, but once I started to see what Leo and Diane Dillon and others were doing this incredible range of stuff stylistically and the stories they were doing, it kind of felt like it might be a place where the things I was thinking about might fit. It turned out it was. [laughs] That’s where I started and never looked back. Along the way I clearly wanted to bring other influences to the work I was doing in picture books, specifically comics storytelling techniques.

Of all your picture books I really love The Three Pigs. Could you just explain what you did with the story?

Of all your picture books I really love The Three Pigs. Could you just explain what you did with the story?

There are all these different threads that have been floating in and out of my work since I was a kid. The idea of alternate realities, the multiverse, is one of those motifs. The first place I encountered this idea was in a Droopy Dog cartoon – for the longest time I thought it was a Bugs Bunny cartoon – where the character is running running running and then skids right out of the film. You see the sprockets on the edge of the film frames and the white space behind it. The character then runs back into the cartoon and keeps running. I loved that there was a world, a seemingly blank world, outside the reality of the cartoon. Duck Amuck is another classic where the hand of the animator comes in and is messing with the actual cartoon. There are of this idea examples in MC Escher and Magritte. I was always drawn to that visual representation of looking behind what seems to be reality.

I thought about how I could do that in a book form. I had all these cool ideas about things that could happen visually, but I needed a story. I began thinking that I’d have the characters come out of the story. I began by trying to write that story, but that didn’t work, because no one – including myself – would know what that story was and who the characters were. It was very confusing. At some point when I was drawing in my sketchbook I drew a few well known characters, and I thought, what if I start with a story that as many people as possible would know. That way you can just forget about it because you already know the characters and what happens.

Pigs have been a recurring image in my drawings ever since I was in high school. I just love drawing them. They’ve turned up in smaller roles in some of my other books. I thought this is great, pigs can be my main characters. The motivation was certainly there. They’d love to get out of that story because the first two get eaten up every time the story is read. I didn’t want it to be just a lot of winking at the adult audience and look how clever I am. It had to be a story that was understandable and accessible to an audience of kids. From a story standpoint, hopefully it was funny, but I wanted the reader to care about the characters and to have a satisfying resolution.

You needed characters who had a reason to escape their story.

Exactly. You have to legitimately create a story that kids are going to want to read. That said, all of my picture books seem to have this huge age range from the very young to practically to adult. The book absolutely has to be accessible to a young child. I’m not going to dumb it down – kids are very visually sophisticated.

So as far as Fish Girl, had you been thinking about making a graphic novel for a while?

So as far as Fish Girl, had you been thinking about making a graphic novel for a while?

Yes. As with anything that I do, when I have a story, I have to find a solution to it. The app that I did – Spot – was a story idea that up to that point I hadn’t been able to make work in book form. It turned out that a tablet was a really great way to explore it. Fish Girl grew out of a long standing idea that I’d been making drawings for and tried several times, unsuccessfully, to turn into a picture book. It was centered around the image of a house full of water that fish lived in. It was just a visual image, which is how most of my books tend to start, for which I had to discover the story.

I was writing pages of notes and drawings in my sketchbook. During that time I was seeing how the graphic novel was really beginning to take off. I looked at Alison Bechdel and Chris Ware and these really beautiful visual books and I wanted to be part of that. I began to look at my story as the place where I could make my entrance into that longer form storytelling. It took a while mostly because I wasn’t sure technically how I was going to do the work. I didn’t want to spend ten years doing it. I had to work somewhat simpler than my picture books. Finally I said to myself, I have to do this now or I’ll never do it. I decided to ask an author friend, Donna Jo Napoli, if she would collaborate on the writing with me.

The first draft was about 300 pages. It was too long for the story. Also, as I was going to do it in full color, the retail price would have been too much at that length. I had to find the price point and the page count where it can work. We ended up at about 200 pages. The reality of the story that developed dictated the way that it looked. I had a whole backlog of visual ideas. I was finally doing this longer book and I’m was going to try everything I ever wanted to do – which of course was just too much. It ended up being quite simple. I didn’t get crazy with the layouts. I worked my like I do in a picture book, using double page spreads and single pages and multi panel pages and mixing them. I had drawn floor plans and diagrams of the house that I thought I could intersperse throughout the story. I had newspaper accounts that filled in backstory and a whole lot of other information. Ultimately all that material just slowed down the narrative. The drama builds and it felt extraneous - so I just left all that stuff out.

Ultimately the story drove how I approached the art. In the end I was fighting for every page. I had to take each scene and ask what the essence of it was. How can I get all this information in and have it be readable and convey everything that it needs to. I would have loved to have gone off on wandering tangents of cool visual stuff, but ultimately I didn’t have the space to do that.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about it in that way because of course in picture books the dimensions may change but you have this page limit and here where you could do anything you needed to go, okay, what are the limitations I’m going to establish.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about it in that way because of course in picture books the dimensions may change but you have this page limit and here where you could do anything you needed to go, okay, what are the limitations I’m going to establish.

If I had made the choice to do the book in one color – like This One Summer, by Jillian Tamaki – I could have gotten more pages. That book is 320 pages. But I need color. That’s just the way I work. I really need that complete palette. For this audience, a middle grade audience, there’s a price point where it becomes too expensive. I want it to be accessible to families who aren’t prepared to shell out fifty bucks for a book. Coming out of picture books where I’m always acutely aware of space, it wasn’t hard for me to think that way.

With the app Spot, I went into that thinking, it’s digital, so it’s limitless. I was doing all these drawings and the developer said, you know, we can’t fit all that stuff in. They said, there’s a limited amount of space for the assets before we use up the digital space. We can’t have these worlds take thirty seconds or a minute to load. A viewer would just walk away. Once I understood form and the limitations, I could design things to fit in it. Even in the digital realm, there are parameters.

For that project, all the environments were done piecemeal. Everything was a separate drawing that was digitally combined. A lot of things could be repeated. You make one piece of seaweed for example and it can be replicated any number of times without adding more space. That was great. I made to make things modularly whenever I could. Then there were the unique elements, but again, with limits. I loved doing big things, playing with scale. But one gigantic character would eat up too much space, so out went all the really large characters.

So even though you’re not printing and binding the book, you’re very conscious of the process and the technical requirements of making a book.

I’ve done all the books that I’ve written with the same publisher and the same person, Donna McCarthy, was the head of production. I’ve been on press with her with all my books. It’s great to watch the book being printed and the how the press men adjust color and all the factors that go into that and understand that. If, for example, the trim size of the book goes over a certain dimension in one direction they may have to move the book to a larger press and that alone could add a dollar to the cost of the book. At the start of a project we would sit down and talk about things like where it is going to be printed and how big the presses are. If the trim size I chose is, say, an eighth of an inch too big for the press, I’m happy to reconsider this small adjustment to help keep the price of the book down. Learning that sort of stuff was great. Understanding how a book is produced was really interesting and useful for me.

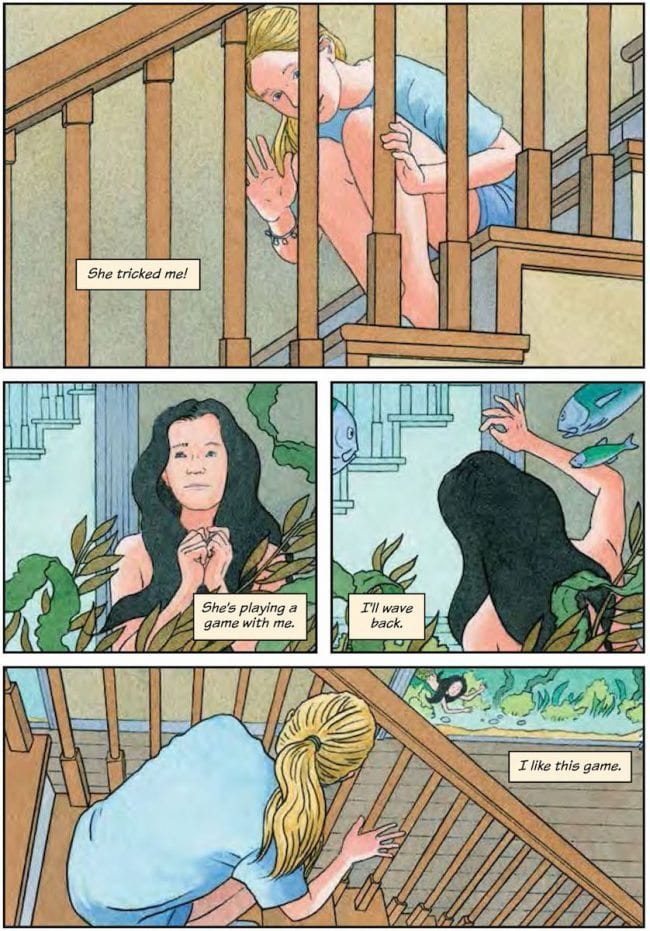

For most of Fish Girl, Mira never speaks.

Until the end when she realizes she has a voice and uses it. Visually that meant keeping her thoughts within the square thought box. When she finally speaks, that dialogue appears in a classic word balloon. It was a nice visual touch.

What’s the dramatic challenge of telling a story where the main character is silent?

It becomes about facial expressions and gestures and body language. How big she is in the frame to reflect what’s happening. To emphasize the feeling, whether it’s one of happiness or sadness or fear. Trying to use those visual elements to heighten the emotions. She is expressing them in her thoughts, to some degree, but I have to really try to visually accentuate what’s going on. In the same way in a silent film where it’s often a little more theatrically expressed because we’re getting the impact of that emotional state through the images.

Initially the character of Neptune lived in the house and it was driving me crazy because Mira comes out of the tank on a regular basis. She exercising to build up the strength in her legs and I couldn’t have her continually sneaking around so he didn’t hear. If you set that up you need to have a close call or two where he hears something and goes to see that she’s in the tank so it couldn’t have been her, but why is the floor wet? There just wasn’t room for that. I thought, what if he doesn’t live there? Get him out of the house and then it became a place where it was the only time when she had that space to herself. Otherwise she’s always on display, always this specimen. But now, at night, she is free to just swim around the house unencumbered without anyone observing her. Visually that was really nice – the night sky, the darkened rooms, her swimming around. I would have loved ten pages of nothing but that. [laughs] At the end I could only get a few pages of that in there.

In the spread on pages 108-109, you made this decision when she finally sees the ocean not to show her face, to depict this moment from behind. Why?

That came very early in my sketching. She’s always been in that house looking through the filmy windows at the ocean, but now she’s confronted with the enormity of it. The thrusting the arms out and embracing the waves, the standing back, catching the moon in that vista, was immediately what I saw. Not her face and the potential rapture on her face, but the whole body gesture of it. The arms spread, the embrace. If I was showing it from the front and if we were seeing her face, we wouldn’t be seeing the ocean. To me it needed that double page spread of the water and her in front of the water and the enormity of what that must feel like. I wanted to make the viewer feel a part of what she’s experiencing.

You mentioned that you had been kicking this idea around for a while. Was the process different from making a picture book? Or was it just longer?

In some sense it was just an expanded version of how I work. The nice thing was we didn’t sit down and write out a finished text. We had a first draft and then I drew out a complete rough version. We then modified the story based on our reaction to that. I drew it again. And again. It was a nice back and forth where the art and the text were able to inform each other throughout the process, which is something that I wanted. Eventually I had a complete rough version in pencil with all the dialogue dropped in- not even word balloons, I just cut and pasted text - and I had pretty much defined what was happening on every page. It was pretty close to the way it ended up. Of course, then it was, oh my god I’ve got to make this thing! [laughs]

I met Chris Ware a couple of months ago for the first time and he asked, how long did it take you to do this? I said I don’t know, three years? He said, gee that’s pretty quick! [laughs] Then it was just doing it for months and months. I drew them all in pencil on vellum. I scanned those drawings and got this nice dark line. I reduce them to print size and printed them out onto watercolor paper. Then I did the painting. The drawings took about five months. And then it was back to page one and I’ve got to paint them all! I gave myself a goal of doing at least two pages of color a day. I got close to three a day as I got into it, but it was making that choice of I’m going to paint this in a way that I can achieve that goal.

Unlike in the picture books where I work on a painting until I’m done with the painting. A double page spread might take me two weeks. I don’t use an ink line – or any line – in my picture books. But here, that black line was going to hold the shapes and the forms. I felt good about the color, but clearly it isn’t painted in the same way that I do a picture book. I’m sure anybody who does graphic novels must go through the same sort of investment in time and debate over speed and ability. It’s an enormous amount of work. I had thought about doing the color digitally because I love digital color, but while I know the process, I’m not fluent with it. I could paint faster than I could do it digitally. Plus, in the end I’m glad I painted it because it has a different look and it feels more like my work. If I were doing another one I’d love to get a colorist involved. I would be happy to be the overseer and director.

At the beginning when you were writing with Donna Jo what kind of drawing were you doing in the early stages as you were working out the story?

At the beginning when you were writing with Donna Jo what kind of drawing were you doing in the early stages as you were working out the story?

The first version had the most detail in it because both Donna Jo and my editor had never done graphic novels before. I had a reasonable idea of what it was going to look like, but they had to be able to get a sense of it. So the first three hundred page draft that I mentioned had a fair amount of detail in it. I didn’t labor over the drawings, but they’re refined enough that someone could fully read what’s happening. They got looser later on, because I did that first version more for their benefit than my own. The last rough version was quite loose. Then I went out and found models to use. I found a young girl on a local swim team and the coach shot footage on an underwater video camera so I could get that swimming posture correct.

You’re used to doing a few drafts of rough pencils to work out the story?

Right. The picture books have many versions, too. I still do it the old fashioned way because I like the physical materials as opposed to working on the screen.

You mentioned that you got a model for Mira. Do you use a lot of models?

It goes back and forth depending on what I’m doing. For this I wanted a more representational approach to the characters rather than something cartoony, for lack of a better word. I get enough reference for what I need. I don’t pose everything for every panel. They have to look like the same character all the time so I’m getting coverage of profiles and frontal views and from a higher angle or lower angle. For this book, Neptune was my kid’s Latin teacher. Livia is the daughter of a friend. She just had the personality of that character, she was perfect.

I also built an eighteen inch high model of the house that I could take apart to see the spaces. I didn’t use it all that much. The act of building it was kind of enough for me to mentally imprint the space in my mind. I didn’t have to go back and refer to it a whole lot, but I do that kind of thing all the time. I almost always make models of my non-human characters. Crayola makes model magic a really lightweight modeling compound. The models are fairly rudimentary, but I can draw the mass and the volume and the feel of it very quickly. I can make a rough drawing and then put away the model and refine the drawing.

Having made picture books, now having made a graphic novel, do you think there’s a big difference between the grammar of how a picture book works and how a comic works?

There’s a lot of overlap. I guess that somebody’s studied this. I don’t know where the dividing lines are at the very young ages because kids are so visually literate now, I’m wondering how complex a set of panels can be understood at what age. Maybe I’m not giving kids enough credit, but I tend to simplify it because I want to really make sure there’s no misunderstanding. The way I look at the picture books is that I’m doing a streamlined version of that language – although my kids were reading comics pretty young so maybe there’s no need to do that. That’s a good question.

It’s funny because I do know that confusion can come in at the adult level – particularly for people who don’t know comics and how to read them. Which direction am I going? Left or right or up and down? It’s usually adults who look at my picture books and say, “What is this? I don’t get it! Where are the words?”

Having made Fish Girl and I don’t know where you are with your next project or thinking about what’s next but has it changed your thinking about what you want to do?

I really enjoyed working on a longer form story. I have a couple things in mind that, now that I’ve done a graphic novel, look to possibly be in that format. I think having done one the way I did it, I would definitely be open for different approaches. Maybe working in a more line-based, looser style. Doing something different would be interesting.

It always starts with the story. I think this experience totally unlocked my ability to think in terms of a bigger canvas. I am currently finishing a picture book right now and I’m going to have another one to start when it’s over with, but I have a couple of ideas that feel to me like they would be some sort of visual novel. We’ll see what happens.

My last question for people doing this is usually, has this made you want to make another or never again?

[laughs] It has in fact whetted my appetite for it. It just takes real planning, knowing the time commitment. I’m not one who cranks out picture books. I’ve never done one that takes less than a year. I just have to factor that in. Prior to this, it’s always felt it just so daunting. And while it was a lot of work, I now know what it takes. I can now think of stories in a broader way than I might have before.