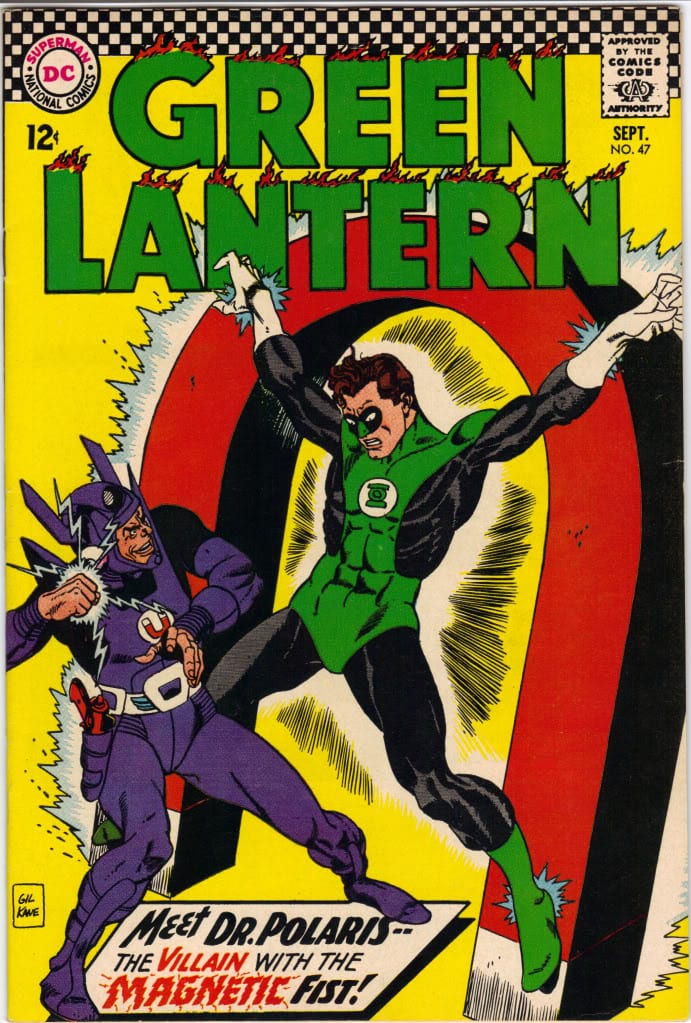

Today on the site, Ron Goulart returns with his column about Connecticut Cartoonists. This time, he focuses on three: Leonard Starr, Warren King, and Gil Kane (his collaborator on Star Hawks).

A time when adventure strips were dying and funny ones were filling their slots was probably not an ideal time to try to peddle a jumbo one. But, since it had long been my ambition to write a comic strip, I did not share my thoughts with Flash Fairfield. I did, however, suggest that instead of a Raymond idolater, NEA hire a popular contemporary comic book artist who was steeped in science fiction and drew in an up-to-date manner. Specifically, Gil Kane. Nobody at NEA had ever heard of him, but when they saw samples of his work and learned that he’d drawn Spider-Man, they were impressed. NEA and United Features had a dinner for all their Connecticut artists, writers and executive. After the dinner Gil and I were invited to have drinks with some of the visiting executives. One of them asked Gil if he could send him a drawing of Spider-Man for his grandson. And he said, “My boy, I’ll draw it for you right now” and turned over the large paper place-mat and drew a complex drawing of Spidey swinging through a Manhattan nightscape. The executive was obviously delighted. And I thought, “We’ve got a deal.” And we did.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Interviews & Profiles. Biographer Michael Maslin talks Peter Arno.

Q: It's hard to imagine the magazine without Peter Arno. How responsible was he for the development of the modern New Yorker cartoon?

A: Ross called Arno the New Yorker's "first pathfinder"; it's true that Arno was, in those early years at the magazine, finding his way, along with Ross, and Rea Irvin, to what we now recognize as the New Yorker Cartoon. Could the New Yorker Cartoon have happened without Arno? His two peers at the top of Ross's ranked artists, were Gluyas Williams and Helen Hokinson -- both incredible artists, both well represented in the magazine. Their work was graphically opposite Arno's: gentler; their captions subtle. Arno's work hit hard and fast. He wanted the readers to experience an instantaneous connection: drawing, caption, Bam! Had his work not been in the mix, who knows if the magazine's cartoons would've headed where he took them.

The Guardian talks to Simon Hanselmann.

When not putting himself in mortal danger, Simon Hanselmann is responsible for the cult comic series Megg, Mogg and Owl. “If I don’t do stupid things every now and then, I will run out of stupid things for Megg and Mogg to do,” he says. “If I stop being a fuck-up, then Megg and Mogg will soon just be about managing European translations and Skyping with network executives.”

—Commentary. Longtime Mad editor Nick Meglin remembers the magazine's art director, Leonard Brenner.

During one long, boring cover conference going nowhere, Lenny finally stood up and with a colorful display of profanity stated that he had had it and was going to lunch. Seizing a similar escape route, I followed, flashing a middle-finger salutation saying, "Here's our next cover idea, guys — MAD, The Number One Magazine of Good Taste," and exited.

When everyone cracked up, Lenny did an about face and declared, "Now, that's a great cover idea!" He was dead serious and so insistent that several of creative team started to lean in his direction. I pleaded, "Hey guys, it's just a joke, let it go," but despite my protestation, the group voted to show the mock layout to our publisher, Bill Gaines, the final arbiter of covers (his one editorial involvement in the magazine's content).

Bill asked incredulously, "Do you really want to do this?" I said, "Not me, Bill!", prompting Lenny to describe me in a volley of adjectives of which "chicken-hearted bastard" was the most complimentary and mentionable in mixed audiences. He ended his tirade with, "…and people will be talking about this cover for years to come."

—Misc. Frank Santoro is auctioning off Chris Ware art to raise funds for the Comics Workbook Rowhouse Residency.