Ronald Wimberly is a multitalented artist, writer, and editor. He created the graphic novel Prince of Cats as an interpretation of Romeo and Juliet set in 1980s New York City; drew a collection of quotes from black luminaries, Black History in Its Own Words; and is currently working on Sunset Park, all published by Image Comics. His newest project is the tabloid newspaper LAAB Magazine, a collaboration between Wimberly and Beehive Books. LAAB #0, subtitled “Dark Matter”, touches on the intersections between comics, pop culture, and fine art, and features work by and interviews with artists like Saul Williams, Trenton Doyle Hancock, and Alexandra Bell, as well as comics by Wimberly, Richie Pope, and Freddie Carrasco. I spoke with Ron by email.

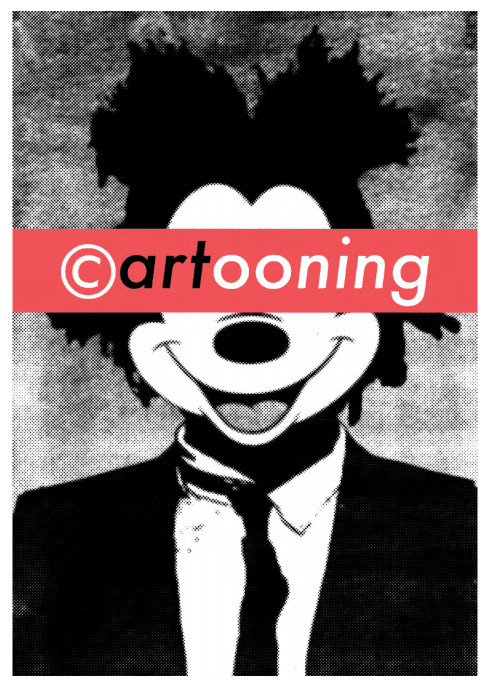

ANNIE MOK: In LAAB #0, you use Mickey Mouse a couple of times as a richly layered visual motif. On the cover, a poster in a NYC street scene shows a group of men tearing down a Mickey statue like it's a war monument. In another image, you layer Mickey's face over Jean-Michel Basquiat's, but obscure the eyes with Barbara Kruger-style typography. Can you break down why you used Mickey in this way, including how Mickey's origins and influences may have factored into your playing with this corporate icon?

RONALD WIMBERLY: LAAB #0 deals with the political unconscious in pop culture aesthetics. These images are meant to provoke thought. Honestly, they seem embarrassingly didactic as is, a bit on the nose; describing my intention defeats the purpose of looking at the work. So instead of answering your question directly I’m just going to give some more context to the information about the subjects in the pictures and let people contemplate the images.

Mickey Mouse, as readers may know, is the flagship character and brand icon of Walt Disney Corporation. Mickey Mouse is recognized around the world. Mickey Mouse was designed by Ub Iwerks; I think a lot of what Disney is can be summed up in this first relationship between Walt and Ub.

I would encourage readers to look up the Disney animators strike of 1941.

–I forgot to mention how Disney park revenue is going up, but many of the park workers are so poorly compensated they are homeless. Just last year a parks employee, Yeweinisht Mesfin, was found dead in the car she was living in.

In the US, one can figure if an idea or image is in the public domain by finding out if it was published before or after Mickey Mouse. Disney lobbied extensively to change copyright law and in 1998 the Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) was signed into law, adding an extra 25 years of copyright protection to Mickey Mouse. Mickey Mouse will go public domain in 2024 or something (citation needed).

In 2009 Disney bought Marvel entertainment, acquiring the copyrights to all of the Marvel Comics IPs including those that were disputed by their creators (among them Jack Kirby and Stan Lee).

The cover image references the second shot in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, as readers may know, is an iconic artist from the late 20th century. Basquiat considered himself a failed cartoonist; I consider him one of the greatest cartoonists of the 20th century. When he was a kid he lost a drawing contest to a kid who drew a “perfect Spider-Man." He referenced cartoons in his work and he watched cartoons while he worked. Basquiat appropriated images from comics and pop culture and used the copyright symbol liberally. Basquiat’s work often interrogated the spectacle of black identity.

Identity is often commodified in art and cartooning.

In the LAAB Manifesto, you write, "LAAB is a laboratory. LAAB is a process not a product." This reminds me of my old teacher Kinji Akagawa's idea of art as inquiry. What about this plasticity, this flow, is important to the visions you're laying out in this paper?

This acknowledges the struggle and the paradox of the work. Struggling to practice art as an interrogation of form and subject while at the same time presenting a commodity to support that struggle, which itself is a struggle against that very commodification. I think the ultimate triumph will occur when readers engage with the work and interact with it. Hopefully the paper also makes a case for different ways of thinking about the production and interaction with aesthetics.

LAAB's pages reference many fine artists, including among others Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall. How do you see yourself and your work in relation to artists like Walker, Marshall, Basquiat? A lot's been made of the pleasures and pitfalls of comics as "low" art, and I'm curious if you see comics this way or disregard such a binary altogether?

As for how I see myself, I mostly disregard this binary; it does not affect how I see my identity. It’s only interesting to me in regard to what it says about our cultural moment or how it helps my hustle. I think a lot about the relation of value to types of production (material, mechanical, digital, etc.); I don’t think of it in terms of high and low art except to understand how others or the market may frame relations as "High vs. Low.”

You mention your art school background—what was art school like for you? Did you have any formative experiences with teachers?

Art school… I went to Pratt Institute in '97, went nearly full term, and dropped out rather than pick up my remaining credits. It was very formative. Pratt seems to have made a shift. Back then, the value of the school wasn’t visible, but the faculty and the student body was very nourishing, rich; now it seems to be the opposite (the campus looks GREAT!). Back then, punk bands would perform in an alley between the Industrial design and the Communication Design building; now that alley is a beautiful annex that connects the two buildings. (You can get Starbucks in there!) Me and four other students resurrected the Black Student Union; I learned a lot from that experience… It didn’t last very long after we left Pratt. Of the teachers that had the biggest influence on me, I believe two still work at Pratt (Rudy Gutierrez, Floyd Hughes); two important teachers of mine, David Passalacqua and Charles Goslin, have since passed away. David taught me how to dig. Goslin taught me how to build a critical framework for looking… both helped me develop my eyes …but mostly just being around so many incredible artists was formative. Many are still my closest friends to this day. They make up my community here and around the world. They’re my family.

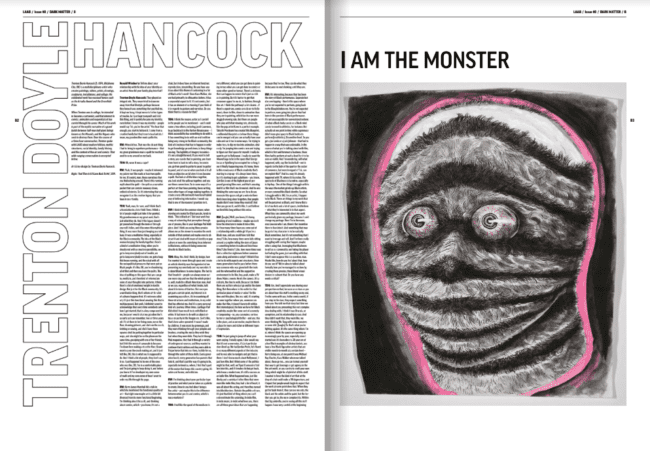

I loved that Trenton Doyle Hancock mentioned Jacob Lawrence, one of my favorite artists, in your interview with him for LAAB #0. Hancock pointed out Lawrence's directness as an image maker, and that quality's commonality with comics. What artists whose work you've encountered has given you this feeling of immediacy or very clear visual storytelling?

Bernard Krigstein, Katsushika Hokkusai, Kuniyoshi, Kunisada, Yoshitoshi, Chris Ofili, Chuck Jones, Jack Kirby, Mike Mignola, Gustav Klimt. There are really too many to list, but those are the ones that jump into my head off the top. By artist, do you mean painter?

You spoke recently on social media about revisiting an earlier work you had complicated feelings about, your graphic novel adaptation of Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. What's it like to revisit and reassess older work of yours?

It happens. I am still on the road on occasion, unpacking and selling old works. I got a big box of remaindered Something Wicked; they keep the table from looking too bare. I picked it up and looked inside it recently. It’d been long enough for me to ACTUALLY SEE IT. I still remembered the process of making it, but now there was enough space for me to appreciate the job I had done. Not what I had wanted to do, but not a bad job overall.

On a similar note, your graphic novel Prince of Cats, originally published by Vertigo, was picked up by Image and republished in an oversized hardcover that really showcases your drawings. How did the new edition bring in a new audience for the work? What was it like assembling this version, which includes rough drawings and notes and a new preface?

I almost feel like the Vertigo version was an ashcan.

I can’t say I have any material evidence as to how the new edition brought in a new audience. The book has been successful though. My question would be, 'Why was the launch of the Vertigo edition handled so poorly?'

Putting the new version together was a good experience. I had done a large portion of the work so I could just focus on cleaning things up, adding value, and designing the object to be what it should have been to begin with. The small crew at image actually did a great job of editing the book. Only a few flaws slipped through. I was surprised by how many Vertigo had missed. I wasn’t surprised by how many I had missed; after writing/drawing the book, my eyes can be a bit poor at catching copy mistakes.

You worked as a character designer on Black Dynamite: The Animated Series. With so many cartoonists such as Michael DeForge moving fluidly between animation projects and comic book work, it seems like such a neat interplay of disciplines. What was the experience of working on animation like for you? Is it something you still do or want to do more of?

I’m a bit ambivalent about animation work. There’s such a huge opportunity to express ideas and make images but there’s so much money required to produce animation that creativity and vision can get hamstrung by bureaucracy and marketing. It makes me appreciate great animation even more. It’s a testament to the will of all involved.

I’ll most likely do more animation if given the opportunity.

I low-key want to design games though.

Your book Black History in Its Own Words includes portraits of and quotes by artists and activists like James Baldwin and Laverne Cox, among many others. What was the culling process like for the quotes and people selected to include in the book?

It was all very natural. It was mostly who came to mind with a deliberate effort at accurately representing the diaspora of black voice. There are even a couple of capitalists in there!

LAAB #0 lays out visions for the future, but I'm wondering if you can tell me what specifically you have planned for your next projects?

I’m working on Sunset Park. This is my main focus. I have other things bubbling but not in comics.

What do you hope readers take away from your work?

Ideas. Critical subjectivity and a hunger for engaging the world around them.