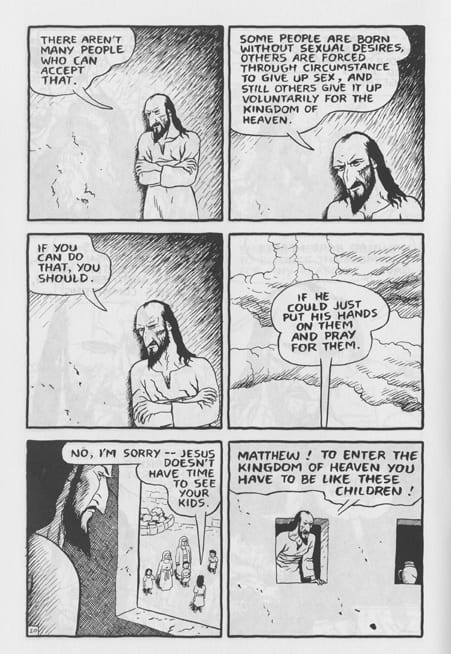

ROGERS: Trying to figure out how Paying for It stands in relation to your other work, I also ended up seeing some connections between this book and the gospels. When you’re adapting Matthew, towards the end of Underwater, you’ve got a sequence where Jesus is saying people shouldn’t get married, and if you can give up sex for the kingdom of heaven, you should.

BROWN: Yeah, it’s startling how much anti-marriage stuff there is in the New Testament. Both Jesus and Paul say similar things about marriage, and Paul has a famous statement in [one] of his letters about marriage, how you should really avoid it, and it’s really just a compromise, you should marry only if you really have to. It’s better to marry than to burn, or something like that.

ROGERS: It seems like there’s a lot of the same kind of sentiment in your gospels. It seems like Jesus berating the Pharisees or going against all these tenets of the culture that he lives in, I think, is something that is part of Paying for It. Not to give you a messiah complex or anything like that. But is that something that appealed to you in the gospels, this rebellion or stance against a society that inhibits personal freedom?

BROWN: Yeah, I mean, obviously that’s there. Whether that was appealing for me? Obviously that is an appealing part of the gospels. I think that’s one of the reasons why they always have been appealing. Counter-culture figures, I think, are always appealing. Or people who are willing to, in some way, push against the restrictions of the society that they’re in. But my main reason for wanting to do the gospels was because I was a Christian and I was trying to figure out whether or not I wanted to remain a Christian. This was my way of really studying the roots of my belief, or the faith that I was brought up in.

ROGERS: Do you see a connection between this book and, say, “My Mom Was a Schizophrenic”?

BROWN: In that both are arguments, or...?

ROGERS: I think that’s part of it. It also seems to me like you’re taking this cultural inhibition or taboo and stepping back from it and thinking why it’s an inhibition or a taboo. Like, why our society constructs schizophrenia in such a way that it’s something to be feared and treated, or why our society approaches prostitution in a way that it’s something to be controlled and stamped out.

BROWN: Right. I do know that once I got interested in politics in my thirties, I started to wonder, “How can I put these sorts of ideas into my work?” It’s difficult. On the one hand, you want to create an interesting story that people will want to read. And if you make it too much about ideas, then why aren’t you just writing an essay? Comics seem to require some level of narrative engagement. So I’ve kind of been struggling with how to do it. It was different with “My Mom Was a Schizophrenic” because that was so short. Because it was only six pages or something, I felt like I didn’t have to have any kind of story there. But for a longer work, how do you keep the reader engaged? And I wasn’t even sure I was keeping the reader engaged with “My Mom Was a Schizophrenic” either. So, yeah, it’s been a struggle. There aren’t that many cartoonists who seem to really try and do that. The first one I can remember encountering was Steve Ditko. I remember encountering his Mr. A stuff when I was maybe 18, and that having a big effect on me at the time, even though he didn’t turn me into an Objectivist. But still I was impressed that someone was trying to express ideas in comics. And I guess the other person who’s really tried to do it in a big way is Dave Sim, with I would say mixed results. Even though I really love Cerebus, I think so many people seem turned off by the way he tried to do it.

ROGERS: Reads was the big turning point, wasn’t it?

BROWN: Yeah. It’s the misogynistic ideas [that] turned people off. But also having huge pages of text. I do tend to think that’s the wrong way to approach the problem. The first cartoonist I remember doing that was... I guess Steve Gerber did it in some of his Man-Thing stuff, for Marvel Comics back in the 1970s. And I remember noticing at the time, you would be reading the comics, and then you’d hit a page of text, and my impulse was just skip the page of text. Even though I loved reading. I had no problem reading books that were all prose. But your brain is thinking one way when you’re reading comics. When you hit a page of text, you’re in reading-comics mode. It’s a different way of reading. So I remember thinking at the time, “Okay, don’t do this.” [Both laugh.] “Don’t have solid pages of text.” So I’ve always avoided that in my work.

ROGERS: Well, but have you? Like, once you reach the end of Paying for It, or even when you’ve revisited—

BROWN: That’s a different thing. Having a page of text in the middle of a comic, I think, is the mistake.

ROGERS: So reading notes is a different experience than encountering a page of text?

BROWN: Well, so much of my thinking about comics does come from reading superhero comics when I was a teenager. I can remember really enjoying reading the superhero comic and then being disappointed when you get to the end of an issue, but, oh! there's still something to read, there’s still the letters page to read. I would enjoy being able to slow down at that point and read the prose of the letters page. So I don’t think it’s a bad thing to give people prose to read at the end of a work. “Okay, I’m at the end of reading of the comic. Now I can shift over to prose-reading mode.” It’s the difference between putting something in the middle and putting it at the end, I guess.

ROGERS: In one of those sections of notes, called “More About the Normalization of Prostitution,” you’ve got a hypothetical future that presents an everyday, normal quality about paying for sex. But in the hypothetical situations, it always seems to be the woman getting paid, and—

BROWN: I think I do say that it could go around the other way, though. To go into more detail about how it could work the other way just seemed like it was going to make that appendix even longer, and I was trying to keep each of those short. But I think I acknowledged that women could be paying for sex just as much as men.

ROGERS: That’s part of what I was wondering—in your section on male prostitution you say that there’s kind of a paternalistic attitude toward the women who are involved in prostitution and that male prostitution isn’t discussed nearly as much.

BROWN: Right. It seemed like I was doing the same thing there. [laughs] Well, I guess I felt like I had to approach it from that way because critics of prostitution are focused on female prostitution and not male prostitution. So if I had written that appendix from the point of view of a man getting paid for sex, critics would have said, “Yeah, but, that’s not what we’re concerned about. We’re concerned about women being paid for sex.”

ROGERS: Right. I was just wondering if you kind of saw these kinds of gender politics being carried forward into the future, this paternalistic attitude.

BROWN: Well, in the present, there are a lot of women who do pay for sex. I bought this book, I think it was called Romance on the Road. It was a book written by a woman who had gone on trips to wherever, third-world countries or the Caribbean or, well, she’d travelled all over the world, actually—and [it was] about her experiences paying for sex. She interviewed several other women about their experiences paying for sex. So apparently it happens a lot for women while they’re travelling. Obviously not most female travellers, but there are quite a few women who do. I also picked up this book about gigolos, about women paying younger guys to have sex with them. Reading that book, I got the impression that it happens a lot more than we think. I think in our culture, men do pay for sex more than women do. But we also tend to not focus on women doing it. Because so many of the people who create our culture are male, we would tend to focus on women being paid for sex rather than the other way around.

ROGERS: It seems like the power dynamics in our society get reflected in our concerns with prostitution, and our concerns as to what degree men are in positions of control in those relationships, and then we ignore or shove to the side—

BROWN: Yeah, for various reasons I think there is a tendency to ignore women paying for sex, even though it happens. Not as much, as I said, but still it happens. Quite a bit, I think. And if prostitution is decriminalized, I think it’ll happen more. I think more women will get more used to the idea of paying for sex.

ROGERS: It’s kind of amazing, the timeliness of the book with the September ruling. I was wondering what your thoughts were on that.

BROWN: Well, obviously I think Justice Susan Himel is a saint. [We should] explain who Justice Susan Himel is and what her ruling was, I think. Basically a case was brought to the Ontario Superior Court about prostitution, and she came out with a ruling which struck down the three main prostitution laws. [According to the Toronto Star, “Himel found Criminal Code prohibitions against keeping a common bawdy house, living on the avails of prostitution and communicating for the purposes of the trade violated ... women’s Charter rights to freedom of expression and security of the person.”] If her ruling stands, then it would basically decriminalize prostitution in Ontario and probably, therefore, a little bit further on, Canada. When that ruling came out I was feeling very frustrated because I wanted my book to be out right then. I was like, “Damn!” [Rogers laughs] I want this book to be part of the debate. So many people were saying right away, “Oh, this changes everything, and now prostitution is going to be decriminalized.” I realized that that wasn’t the case, that either the government was going to appeal, which they did, or if they lose the appeal they're going to attempt to re-criminalize. Certainly if the Conservatives are still in power and they lose the appeal, then they will try to re-criminalize prostitution, probably using the Swedish model—making paying for sex illegal. So I thought, “Yeah, that debate will still be happening, I’m pretty sure, in the spring when my book comes out.” And it looks like that will be the case. I doubt that by May things will be settled. The debate is still going on. But it is good timing, you’re right.

ROGERS: Have you argued any of your friends around to being in favour of decriminalization?

BROWN: Well, there are people who just agree with me, and would’ve agreed with me to begin with. Jeet’s in favour of decriminalization. My brother’s in favour of it. The three friends that I would’ve discussed this with the most, and who are in favour of legalization but not decriminalization, were Seth, Sook-Yin, and Colin Upton. Have I convinced any of them? I don’t know what Sook-Yin’s current stance is. Colin would still be in favour of legalization, not decriminalization. Seth, I’m not sure what his stand is today. So, yeah, probably not. [Since doing this interview, Sook-Yin's told me (Chester) that she now agrees with me about decriminalization.]

ROGERS: Having your friends in the book as kind of sounding boards and debate partners, I thought, was a really interesting strategy. Did you realize when you were doing that that you were opening up a space for the reader to kind of enter into an argument with you or to consider your arguments?

BROWN: Sure? [laughs] I mean, I don’t expect the reader to automatically agree with me. In fact, I realize that many of the readers will enter into the argument and not be convinced by my side of the debate. It’s there to stimulate thinking on the subject. Whether or not it convinces anyone… I hope it convinces some readers, but of course it’s not going to do that for everyone.

-----------------------

[Click here for a bonus "Comics Corner" segment of the interview]