There’s a scene in I Never Liked You, Chester Brown’s ethereal memoir of adolescence, where his younger self greets a friend by saying, “I shit it was you!” I wonder if this isn’t what Brown does in all his work: like dropping a cuss into an otherwise normal sentence, the cartoonist often says what’s forbidden but phrases it in familiar ways.

His early Ed the Happy Clown delights in excesses of castration and scatology, while his autobio work like The Playboy trades in masturbation, pornography, racism, and snot-eating. Why, the artist wonders, are such topics off-limits? When young Brown swears in I Never Liked You, his mother erupts into hysterics—and though the child is silenced, his older self will devote his work to asking why the authorities in our lives restrict both our expression and our behavior.

Brown’s latest book, Paying for It, renews such concerns. This account of his experiences in the demimonde of prostitution both depicts and picks apart the cartoonist’s own sexual proclivities and peculiarities. At the same time, it questions why prostitution has been vilified, and why we define both call-girl and john in terms of criminality rather than commerce.

As I found in the course of this Journal interview, Brown is just as forthcoming and unstinting in his conversation as he is in his comics. Brown was happy to discuss the issues raised by his book, but he also indulged my questions about his process, his influences, and the evolution of his work. So, while Paying for It remains the occasion for our conversation, Brown’s willingness to discuss both Louis Riel, his biography of the Canadian rebel hero, as well as the rebellious Jesus he portrays in the now-defunct Underwater, should illuminate what the cartoonist is up to in his latest venture.

The interview took place during the lead-up to the recent Canadian federal election, in which Brown once again ran as a candidate for Member of Parliament, with the Libertarian Party. Last week, voters gave the Conservative government a majority, which, as Brown mentions below, will throw into question once more the legal status of prostitution in Canada—a sure sign that Brown’s polemic will remain relevant in months to come. But his responses in this interview reveal a cartoonist whose analytical thought does not limit itself just to considerations of hot-button topics. Rather, Brown is an artist who is constantly engaged with the larger and unending questions of representation, of rights, and of how we permit ourselves to live our lives.

SEAN ROGERS: The subtitle for the book is “A Comic-Strip Memoir about Being a John.” Did you do this to deflect expectations about this being a book about prostitution?

CHESTER BROWN: Well, I certainly knew it was going to be autobiographical, and since it is from my point of view, and I’m a john, to me that makes sense as the subtitle.

ROGERS: It just changed the reading experience for me, and my expectations. It’s something that I think you deflect in your introduction as well, saying that this can’t be a book about the prostitutes, that it has to come from your point of view.

BROWN: Actually, when I was planning the book, I was thinking that I would be talking a lot more about them. It was only when I actually started to write the script I realized how little I could write about them. That kind of did change the focus for me. Even then, during the writing of the script, I put in a lot more about them than I should have. When I was drawing the book I realized that I've got to take this sequence out, I've got to take that sequence out.

ROGERS: It’s kind of a “Showing Helder” process, where you’re thinking about the ethics of representing other people, and getting their stories right, and how much you’re allowed to talk about them as individuals.

BROWN: Yeah, exactly. I have the right to tell my story. Whether or not you have the right to tell other people’s stories—I think we should have the legal right to tell whatever stories we want to, even when those stories are about real people, but if you know that telling a story about a particular person is going to hurt him or her emotionally or expose secrets that person doesn't want exposed, you'd better have a good reason for telling that story. So I did have to be careful about what I wrote about all the women.

ROGERS: Coming back to very surface-level starting points, I Never Liked You is subtitled “A Comic Strip Narrative.” Is there a difference between that book being a narrative and this book being a memoir? Do you see a difference in approach? Or is it something that you had really thought about?

BROWN: Well, obviously I Never Liked You could have been called “A Comic Strip Memoir” too. [laughs] It just didn’t occur to me to call it that. I suppose with I Never Liked You it wasn’t as important right away on the cover to make it clear that this was coming from personal experience. Whereas with this book it was. I did want to make it obvious right from the get-go, right on the cover, that this is coming from a personal point of view. So I guess that’s what was different about it.

ROGERS: I was also thinking about our discussions about Spotting Deer [by Michael DeForge] the other night and about whether that book is narrative.

BROWN: Right.

ROGERS: And it seems to me that while the thrust of I Never Liked You is that it is a narrative, a “story,” the thrust of Paying for It is more argumentative.

BROWN: Right. I mean, I was thinking at the beginning about whether or not I should fictionalize the story and not make the main character someone named Chester Brown. You know, make up a name, and still base it on what I went through, but give myself permission to alter things for dramatic purposes. If I had done that, then it would’ve been quite a bit different. I wouldn’t have seen as many women as I actually did see. I could’ve changed things around, and brought the women’s stories into it more. Yeah, if I was trying to tell a story, it would’ve been different.

ROGERS: In the intro, you seem concerned about this anonymity in the book, concerned that it weakens your book, and I’m wondering why.

BROWN: Why am I concerned that…

ROGERS: Why do you think that it weakens your book?

BROWN: Oh, the stories these women told me about their lives, they were so engaging, and I just wish I could’ve put more of that stuff in there. The woman I’m—whatever you’d call our relationship now—let’s call her for the purposes of this interview my “girlfriend,” even though I don’t consider her that. There isn’t a word, I think, for what she is. But anyway, the woman who’s my girlfriend now, if I could have told the real story of our relationship, everything that has happened to us and how we became close and everything, it just would have made for a better book than the book that we have. I was actually asking her in the early part, as I was writing the script, “Can I show this scene, can I show that scene?” She was like, “No, no, no, you can’t show those.” [laughs] What I did show, I got her permission for. But it was obviously very little.

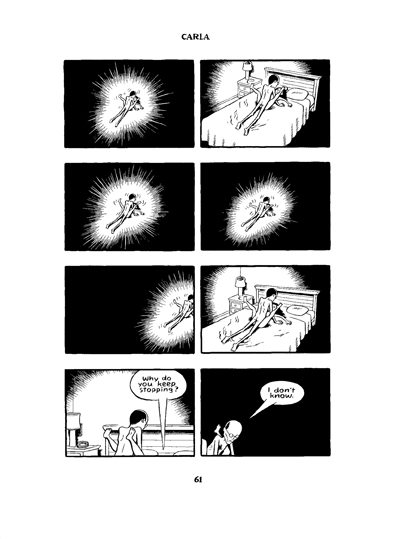

ROGERS: Again, going back to the start of the book, what was your thinking behind all those panels that are black for the initial conversation between you and [Brown's friend and "last girlfriend"] Sook-Yin?

BROWN: [laughs] It probably reads in a way that I didn’t want it to read. Using all black for those panels, it probably seems like it’s supposed to be a reflection of my mood, that even though I’m saying everything’s fine, really I’m emotionally devastated. But that wasn’t the case. I did those panels all black because I just couldn’t draw the scene. I drew it at least four times. I did thirty pages of the book in a different style and decided I didn’t like it, so I scrapped it. I was going over the original art the other day, looking at early versions that I’d drawn of that scene and other early scenes in the book. I kept drawing the scene, and it kept coming out wrong. I couldn’t get the emotional tone right. I would draw her face and her expression and my face and my expression, and it didn’t seem to work. So then I’d draw my head just from the back and her head just from the back, and that didn’t seem to work. At a certain point, I just got sick of it: “Okay, I can’t draw this scene. I’m just going to go on to the next scene.” And the next scene, there was no problem. Part of it is the difficulty that, obviously, there was a lot of emotional turmoil going on inside me, and inside her. It was a difficult conversation for her to have, and how to depict that and convey it, it was too much for me. The next scene, where it’s me, Seth, and Joe [Matt] walking, it was easy. There was no problem with that and the following scenes. So at a certain point I gave up and I didn’t know how to approach it. “I’ll figure out how to draw this later. I’ve just got to move on with this book.” And then I just didn’t want to face it. [laughs] Maybe there is some sort of unconscious pain there. It doesn’t seem like it; I’m not experiencing it. But, for whatever reason, I couldn’t draw that scene, so I came up with this solution of just drawing it all black.

ROGERS: For me, it made a lot of sense. It’s one of these things, like with the subtitle of the book, where it completely alters my expectation of what I’m going to be reading. It seemed to me very much like what the rest of the book was about, in that you were saying, “Okay, this book is not about me depicting emotion. This book is not about me depicting the people in the story. It’s about how people interact, and what those dynamics are.”

BROWN: Okay, good. I still think probably a lot of readers will have the reaction that I’m worried that they’ll have—that they’ll see that as the blackness of my emotional state. But, whatever. You can’t tell people how to respond to your work.

ROGERS: What was the style of the pages you scrapped? Why didn't it fit the book?

BROWN: Well, for one thing, the panels were square. The size of the originals was much smaller, and the drawings were more naturalistic. In the final drawings I usually draw the people looking kind of stiff and there’s kind of a formal look to everything. Whereas I originally was trying to draw everything much more true to life. So that’s the main difference.

ROGERS: And why did a true-to-life kind of style or approach not work for this material, do you think?

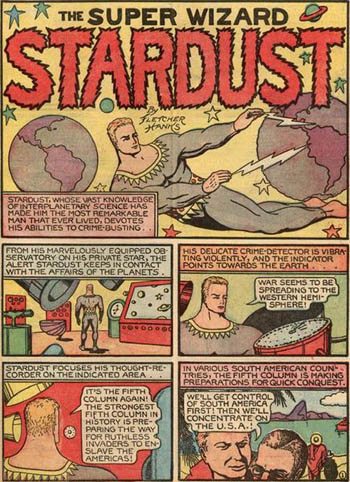

BROWN: I don’t know if it’s a matter of this material. I just decided I didn’t want to draw that way. That book Fantagraphics put out—the Fletcher Hanks book had come out, and I loved the book. And I’m sure he was probably trying to draw as realistically as he could, but it came out in this very stylized, stiff look, and I was like, “Wow, that looks so great. That’s the way I want to draw.” I was actually trying to draw even more like Fletcher Hanks than it ended up looking in the book, but, you know, you’ve got your own style. So it was kind of my style trying to achieve a Fletcher Hanks-like look, but not really coming even close. But that did change the way I was approaching the drawings in the book. So it had nothing to do really with the material of the book. It was just how I wanted to draw at that point in time.

ROGERS: Was it just the style of Hanks that appealed to you? Or did the stories appeal to you as well? His kind of punitive, godlike characters?

BROWN: [laughs] The material’s fun. It’s interesting to read because it’s so quirky and strange. I don’t know that I can say that it really resonated on some kind of deeper emotional level or something, and I don’t think that that approach to storytelling is reflected in the book.

ROGERS: In one sequence in the book, you have Joe Matt saying your relationships paying for sex are cold and clinical, and you counter by saying that they're actually warm and friendly. Do you think that the book succeeds at being a depiction of those warm and friendly relationships?

BROWN: Well, of course not all of them were warm and friendly. I mean there were girls who were very cold. But the encounters that worked, they were more than warm and friendly. I wasn’t as concerned with trying to show that.

ROGERS: I’m not saying that Joe would say this, but would you object to the book itself being called “cold and clinical”?

BROWN: Oh, yeah, no—the book is pretty cold. [both laugh] In large part that’s because of my approach to art these days. One of my favorite filmmakers is Robert Bresson, who instructed his actors to show no emotion. I realized, drawing certain scenes, “Okay, you’ve gotta draw someone smiling here,” [Rogers laughs] but I was resisting even that.

ROGERS: Yeah, the most emotion that you have in the book is that your brow is creased at one point. One little line.

BROWN: [laughs] I guess that was the struggle for me with my stylistic tendency, which is to drain emotion from my drawing style. And what often does really happen, certainly with my current “girlfriend,” [is that] it is very emotional. I feel a lot of emotion, and she seems to feel similar sorts of emotion for me. So that was a fight: how comfortable am I showing emotion, depicting emotion?

ROGERS: I had never made the connection between you and Bresson before, but it makes a lot of sense. Louis Riel seems now, in retrospect, really indebted to something like Lancelot of the Lake.

BROWN: Oh, I haven’t seen that one.

ROGERS: It’s a great movie, but the battle scenes are so dispassionate and measured and distanced. Again, looking back at Louis Riel, it seems like there’s a real kinship there between what you’re doing and what he’s doing. But also with Bresson, even though he is distanced and dispassionate, there’s an emotion that arrives by the end. And I think that’s there in this book a little bit, maybe?

BROWN: Okay.

ROGERS: That, in the process of getting to the final chapter, “Back to Monogamy,” there is a kind of welling up of something you’ve been struggling with, the emptiness that you feel after seeing somebody like Anne, or in other encounters. And the final panel of you, saying something like, “Paying for sex isn’t an empty experience as long as you’re paying for the right person.”

BROWN: “If you’re paying the right person for sex.” Right.

ROGERS: There seems to be a kind of arc or something.

BROWN: Well, yeah, I say it, [laughs] but I’m not sure that I’m so good at showing it. I don’t know—it took me a couple years to even start doing the book, and if I had done the book immediately after Riel, I wouldn’t have had that long relationship with my current “girlfriend.” So it’s kind of good that it worked out that way. It was good from a narrative point of view. [laughter] But I didn’t stay in that relationship because it would work out story-wise.

ROGERS: Even as far back as your first Comics Journal interview you were saying, “Just show the reader what’s there. Don’t involve him too much. Keep him distant.”

BROWN: Oh. Really? I thought that at that point?

ROGERS: [laughs] Yeah. I think that interviewer was objecting to the gospels, or something like that, in opposition to the kind of drive or the always-something-new interest of Ed. But I’m wondering why this is an aesthetic strategy that you’ve adopted more and more over the years, this distance: just show the reader what’s there, what’s in front of him.

BROWN: I guess it has a lot to do with who I find appealing. I got into Bresson because there was a retrospective of his work at the Cinematheque [Ontario], and I remember it would have been with my friend Kris, who I show in the book. We went to see a Bresson film, and we both really loved it, and then following that—do you remember that film with Mickey Rourke? I think it was called 9 ½ Weeks.

ROGERS: Right.

BROWN: We went and saw that right after. And 9 ½ Weeks just seemed so disgusting and overdone [Rogers laughs], and there was no restraint. I obviously found one appealing and the other unappealing, for whatever reason—it’s personal taste, I guess. But it really made clear for me: here’s the direction I want to go in, more in the direction of restraint and not overblown tackiness, or whatever.