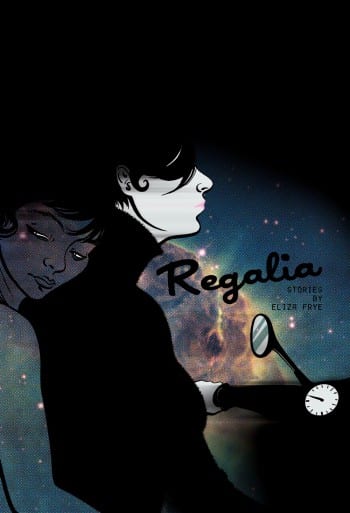

Illustrator-turned-comics artist Eliza Frye has just put out her first book, a rich-looking, embossed hardback with a dark, dreamy image on the dust cover. Using the creative project-boosting site Kickstarter, she brought in nearly $14,000 to fund her project — more than twice the amount she set out to raise.

Regalia is a solid collection of spooky-pretty stories populated by lovely girls and strange guys — or is it the other way around? Focusing on the entwined themes of sex and death, Frye makes use of a rich color palette dominated by bruise-purples and slashes of pink. But her stories have more literary substance to them than that description might make it sound. For a newcomer to comics, Frye's visual storytelling technique is highly developed; in fact, the stories with little or no text are her strongest ones. This is partly because her hand lettering still looks naive, and can takes away from the pages that feature it. But it's mainly because she has such an inventive way of playing with the sequence and arrangement of the visuals. "Gods:Monsters," for instance, consists of tiny panels in color-coded stacks that are meant to be read vertically. Only a few words appear on the two-page piece — "Oh, hello," "you," "so"— but those combined with the stirring images are enough to conjure a story.

"The Lady's Murder," which first appeared online in Narrative magazine and was nominated for a 2009 Eisner Award, is probably the strongest story in the collection, and the most representative of Frye's work. The lady in question is shown through the eyes of the men who knew her before she disappeared, and one of them describes her as "the sort of woman who considered herself a public art." All of the women in the book turn out to be like this. We see them, posing, through a few layers of gaze: Frye's perspective is that of an appreciative, if sometimes regretful, female eye upon the male watcher's vision of a beautiful woman.

Frye herself is something of a performer, appearing in near-costume in stylized photos on her website and book and playing herself in a charming video she made to explain and promote her book project on Kickstarter. She refers to all her stories as "love letters." And although some of its settings are fanciful, Regalia looks like it couldn't have come from anywhere but Los Angeles — which, until a transatlantic move a few weeks ago, is where Frye lived and worked. The Comics Journal talked with her over email for a few weeks while she was busy relocating to France.

The Comics Journal: The story "The Lady’s Murder" opens with some really good sexy-gross butcher imagery. I have to ask, do you know the poem "Veal" by Phyllis Janowitz? I bet you'd like it. It's a favorite of mine.

Eliza Frye: Agh, no! But that's my new favorite poem!

TCJ: When I read your comics I want to get out my Six Feet Under DVDs, reread Francesca Lia Block — all my favorite dark L.A. stuff — and when I first saw your work it put me to mind of Dame Darcy, whose style, to my east coast eyes, looks very much of L.A. Do you think the culture or spirit of Los Angeles informs your work?

EF: From the stark color contrasts to the peculiar sense of emptiness present in the narrative, the spirit of Los Angeles definitely haunts Regalia. I would not term myself an "L.A. artist" because I naturally resist defining myself by place, but I did go to school there and have lived all over the city for the past ten years (and watched Six Feet Under religiously.) I think it would be impossible to avoid the influence of such a strong place. I once heard the experience of living in Los Angeles likened to being stuck in a dysfunctional relationship, and I quite agree. It is at once beautiful, abusive, ugly, sexy, and highly addictive. We're currently in a trial separation period.

TCJ: Ha. You and L.A. you mean? Are you thinking of moving away?

EF: I just did, actually! I moved to Paris last Monday.

TCJ: Oh my word, that's exciting. You mean you've been answering my questions in the midst of this big move? What are you doing there?

TCJ: Oh my word, that's exciting. You mean you've been answering my questions in the midst of this big move? What are you doing there?

EF: Making comics of course! I'm actually still buzzing from attending the comics festival in Angoulême last weekend. It's a huge four-day affair spread out over this adorable country town in the southwest of France and, apparently, the second largest comics gathering in the world, after Comiket in Tokyo. It was literally like a town-sized party— thousands of gorgeous books, hundreds of creators from all over the world, beautiful exhibits and presentations, workshops and concerts, special events for children, and amazing food and wine. I'm still hungover, in the best possible way.

TCJ: In the book, your bio says you'd never made a comic before you wrote "The Lady's Murder." Why did you decide to tell the story this way? Did you enjoy reading comics before you began making them? Whose work do you like?

EF: I created "The Lady's Murder" as a comic because I was trying to explore new styles of visual storytelling. I was going to Calarts at the time and originally planned the story as an animated film, but I had so much fun making the comic that I eventually abandoned not only the film, but my animation career as well. Comics bit me really hard.

Can I tell you a secret though? I don't read very many comics. I love the medium, and could expound at length about its fantastic qualities and unique strengths, but I find it very difficult to connect to superheroes, lazy art, and stories about insecure but well-intentioned teenagers. I'm snobby, I'll say it. But I do regularly enjoy the following webcomics: Sauceome, Pictures for Sad Children, Freak Angels, Darcel, and Star Fighter.

TCJ: Yeah, I don't care about superheroes either. (I often enjoy reading about insecure teenagers though.) But like you I do have a few webcomics I love. I find it interesting that someone who hasn't tended to participate in comics fanboy/girlism, like you or me, can find web comics they read regularly. Maybe it's not just the medium that's different, but the culture surrounding it — maybe web comics serve a need for people who can't connect to comic book store culture.

EF: Yes, I think webcomics are vastly more accessible than comic book stores. I've personally almost always felt uncomfortable to some degree in comic shops, with Challengers in Chicago being a notable and shining exception. But besides the lack of "take your dirty girl-cootie money elsewhere" attitude, there are, I think, two much more important primary benefits to webcomics: Firstly, the selection of stories and art styles available is nearly endless. If you can read there's a webcomic out there that you will love, and conversely if you can write and draw there's at least one other person who will love your work. Secondly, the content is almost always free, making it about 1,000 percent more accessible than print. I'm much more willing to try new comics, even if I think I probably won't like them, because the cost is just a few moments of my time. I literally have almost nothing to lose.

TCJ: What's special about that place?

EF: Oh, it's just about the best comic store I've ever visited! They understand and celebrate comics as a medium, not a genre. For example, they pretty much only carry comics (not toys, card games, etc) and their graphic novels are organized alphabetically so that all of the publishers and countries of origin are mixed up together. I'm surprised I've never seen that anywhere else.

TCJ: I'm curious about your term "lazy art." Do you mean that you find comics folks getting away with laziness more than, say, commercial artists do?

EF: I actually feel like I see it in larger, "commercial" comics far more often than in creator-owned works. I take it as a direct measure of an artist's personal investment in a project.

TCJ: Were all the stories in Regalia first published as digital comics? What did you find useful or satisfying about putting them into print? What did you find difficult or limiting about the print format?

TCJ: Were all the stories in Regalia first published as digital comics? What did you find useful or satisfying about putting them into print? What did you find difficult or limiting about the print format?

EF: Most of the stories in the book were published online first, something I would ideally like to do with every project. For me sense of audience interaction is invaluable. Not only did I get immediate feedback on my work, but I was able to build an audience as well. It also made converting the book to print much easier because thousands of pairs of eyes had already seen it. I certainly would not be where I am today if I had not put my comics online.

The main limitation I see regarding the print format is money. Books are very expensive to print and distribute, and beautiful books cost even more. Luckily the internet has a solution to this problem too: Kickstarter! I produced Regalia thanks to a Kickstarter campaign last fall that raised $14,000. Needless to say the project would not have been possible otherwise.

TCJ: Could you talk about your experience using Kickstarter? I know a number of people who have used it to fund their projects, and recently I read that the NY Times called it "the people's NEA." Someone else told me that Kickstarter has been called the world's biggest "publisher" of indie comics. It seems like an awesome resource. But I wonder, did you feel a pressure to make a kind of "brand" out of yourself in order to market your project on the site? You have to stand out from the crowd in some way, right?

EF: I could talk for days about Kickstarter! It such an exciting new platform, and I feel very lucky to be apart of it. Regalia definitely wouldn't have been possible otherwise. The thing that shocked me the most about the whole process was that the majority of my backers found me through Kickstarter itself. I expected it to be more like Etsy, where you have to bring your own audience. But instead it seems that people are "shopping" Kickstarter, and that's an extremely powerful thing because it means that a project's success does not primarily depend on how famous you are or who you know. It depends on how good it is. That alone makes Kickstarter so much better than the NEA.

I wouldn't say that I felt pressure from Kickstarter in particular to formulate myself as a "brand." I would say "personal branding" is rapidly becoming an integral part of succeeding as an artist online in general. Someone recently emailed me asking for advice on how to build an audience for a new webcomic and basically my answer was, "make really really good shit (and look good doing it.)" When you're promoting your work online you're essentially competing for a chunk of people's time online, but that precious chunk has already been allocated to someone else. This means that you have to be better than all of the other webcomics your audience is currently reading, because they're already emotionally and practically invested there. But more importantly, it means that you're also competing with the rest of the internet— news sites, blogs, Lady Gaga, Justin Beiber, porn, and worst of all, cats. Yes, you definitely have to stand out from the crowd.

TCJ: As someone who makes zines and books I'm curious about how you chose the printer for your book, and what kind of paper you used and why.

EF: I found my printer (Sheridan Books) online and chose them because they appeared to be very friendly towards new independent publishers. Since I come from a background in web design and always want to use Photoshop (a dirty word in print) for everything, I knew I needed all the help I could get. However, unfortunately, they did not turn out to be very helpful or even particularly professional, and in retrospect I wish I had printed in China like I had originally planned. It would probably have been simpler, possibly even faster, and definitely cheaper.

I went with 70# matte white paper because it's a decent stock without being crazy expensive and handles blacks nicely. I'm used to seeing all my comics on screen, so of course I wanted the blackest possible blacks and the brightest possible colors. I could have gone with other papers that might have been slightly better, but they would also have cost significantly more. I made a middle-ground compromise and overall I'm very happy with the final result.

TCJ: I like the pages at the end of your book that show you using chalks to draw the white tigers for "Lucky House" and other details for a story called "Paul." I also love the collages and other found elements in "Lucky House." Could you please tell us about your process there (versus the art in the rest of the book)?

TCJ: I like the pages at the end of your book that show you using chalks to draw the white tigers for "Lucky House" and other details for a story called "Paul." I also love the collages and other found elements in "Lucky House." Could you please tell us about your process there (versus the art in the rest of the book)?

EF: I approach every comic as an individual and therefore try to find the medium and materials that will best suit the story I'm telling. For "Lucky House" I wanted a strong feeling of displacement and detachment, so I worked in a combination of gouache on black paper with ink drawings on milky vellum pasted over the top. The pieces of collage are all from paper items I've collected at Chinese restaurants over the years. I have something of a fetish for ephemeral paper— tickets, cards, stubs, bits of packaging— things that are ubiquitous in daily life but often disregarded and thrown away. So I'm also always looking for excuses to use pieces from my collection.

"Paul" was done entirely in pastel on black paper, and I am going to continue experimenting with "non-traditional" mediums in my future comics as well. As an artist I think it's too easy to use the same medium for everything, mostly because it's cheap and comfortable. Comics especially is very ink-obsessed. But when I teach animation, the class goes through pencil, ink, oil paint, sand, clay, cut paper, watercolor, and charcoal all in a single semester. I'd like to see more of that in comics.