The following is excerpted from the oral history section of The Complete Zap, to be released by Fantagraphics this month. This is the first in a series of Zap features we'll be running over the next few weeks.

Censorship and Suppression

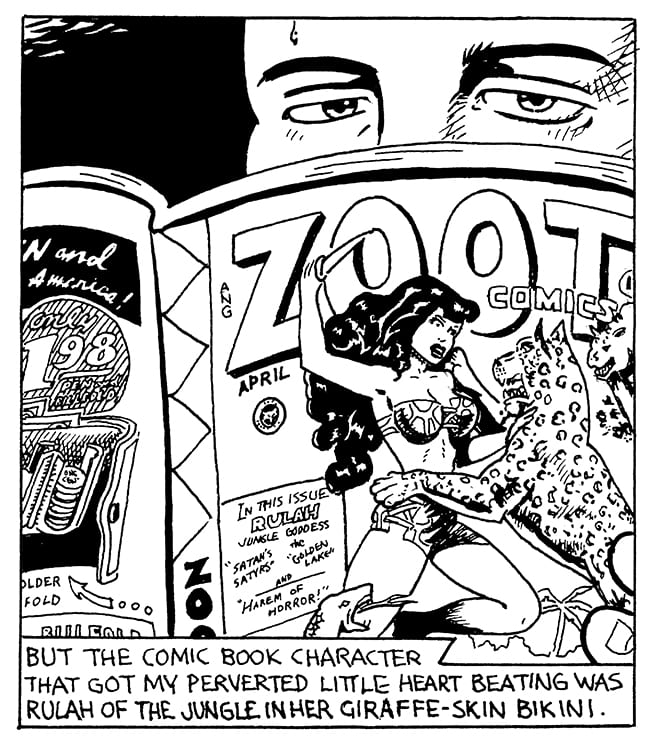

The first underground comix backlash came from the usual suspects opposed to smut and licentiousness. America at mid-twentieth century was chock full of self-appointed, blue-nosed guardians of good taste who tried to control what could be shown in popular media and insisted that everyone follow their rules. Movies couldn’t be released without facing the Motion Picture Production Code. Books like Naked Lunch were banned in Boston and elsewhere, because they depicted perverse relationships. Race music was not played on the radio, and religious groups burned Elvis Presley records. A United States Senate subcommittee investigated juvenile delinquency in 1954 and accused comics publishers of contributing to it. The Comics Code Authority quickly stepped up to police the industry and quash the offenders. Magazine publishers like Ralph Ginzburg went to jail for trying to exercise free speech in print. For a long time, the most conservative elements of American society held sway over everything that could be read, watched, or heard in the media.

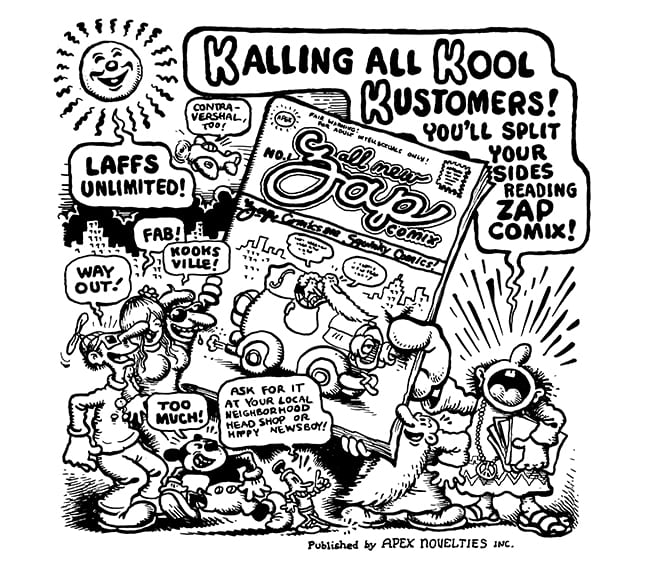

The underground press found a way to bypass all these barriers by creating an alternative production and distribution system. Newspapers and comic books could be printed cheaply in small runs of ten thousand or less and spread around through a network of hip businesses and street entrepreneurs. Nobody in those networks cared about censorship.

RODRIGUEZ: Underground comix certainly broke through that ’50s fantasy that conservatives are so dedicated to maintaining, despite that fact that it was a fantasy in the ’50s, and now it’s an absurd charade. It makes me feel good that we made our blows in the cultural war. We were able to kick the despicable Comics Code in the teeth. We were able to make a living. We were able to reflect our times. It’s kind of a Pandora’s Box of all these threads that weren’t allowed before.

SHELTON: Things began to take a different direction with underground weekly newspapers and Zap. Then Crumb went in with S. Clay Wilson and they participated in a full-frontal assault on censorship laws with Snatch Comics, Jiz Comics, and Felch.

Freedom of the press belonged to those who owned presses, like Don Donahue, and no one could prevent small subterranean publishers like him from printing underground comix. In 1969, Apex Novelties and Rip Off Press quietly produced comic books in a run-down former opera house in the Fillmore District. You had to know someone who knew them to find them. All the authorities could do was to arrest bookstore clerks who sold the comix to the public and bring them to trial.

SHELTON: I remember Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the owner of the City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, got busted for selling Zap Comix, and he paid a $400 fine and he kept on selling them and they never said anything else. Over in Berkeley there was Si [Simon] Lowinsky who had an art gallery and he had an exhibition, and was selling copies of Snatch Comics and he got busted for that. It went to court. It went to trial. The definition of pornography in California is that it has to be of prurient interest and no one on the jury would admit to being aroused by Snatch Comics. It got a not guilty verdict.

With the publication of Zap #4, which included Crumb’s “Joe Blow,” a tale of suburban incest, Wilson’s “Ball in the Bung Hole,” and Shelton’s Wonder Wart-Hog adventure in which he blows a woman apart at the seams with his snout, the dragnet widened. In September 1969, the Berkeley police raided the Print Mint warehouse to seize all their copies of Zap #4, but owner Don Schenker had been tipped off and had moved their stock to another location. When they saw bookstores and distributors getting busted, the Zapsters suspected they might be next.

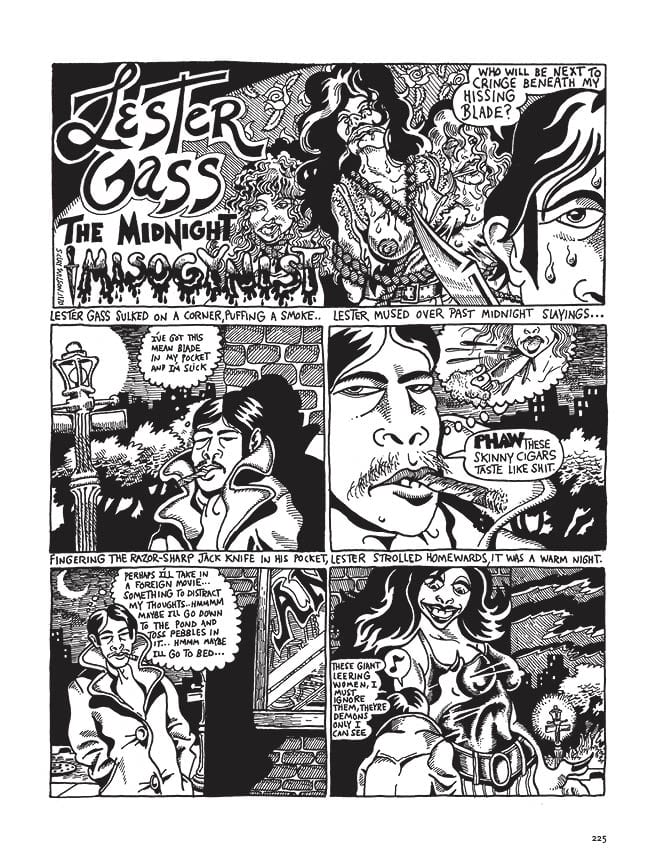

WILLIAMS: We just thought we were all going to get arrested somewhere down the line, because there had never been material like this. Remember, 1969 is when the first adult magazines ever came out that showed pussy and asshole, and this was just flipped, to actually have this in a printed magazine that went through a printing press. You know, anything before that was just some secret thing.

CRUMB: There was an organized, systematic, repressive action taken against every aspect of that outburst against the system, including alternative print media, by the powers, agencies, and institutions of the corporate state. It is not paranoia, but the fact of history to say these things. They didn’t sit back and passively watch while Abbie Hoffman and Huey Newton strutted and fretted their hour upon the stage. They had their think tanks staying up nights plotting and scheming new techniques to squash, neutralize, and co-opt this threat to everything they held dear. They constructed sophisticated strategies for instilling fear into the general population. You could watch it happening all through the ’70s and into the ’80s. Fear was a weapon the bastards used very effectively.

SHELTON: There was a lot of pressure at the time. I guess a lot of people have forgotten how paranoid everyone was, that we were either going to be rounded up and all put in prison camps, or just shot down on the streets by the forces of reaction. Things didn’t look so good in ’68 and ’69.

WILLIAMS: There was a shaky period there in ’70–’71, where we thought the government was going to clamp down. There was a chance there that the country could have swung to the right. We know for a fact that they were reconditioning internment camps in Eastern and Southern California and Arizona where they put the Japanese in, and there were remarks about doing it from the government. We stuck our necks out already so we might as well stick them out all the way and violate everything.

Wilson took the specter of retaliation as a challenge to go even further in depicting the naked psyche

WILSON: My idea is not to entertain them but to enlighten them. Or to make them sick. One or the other. Sometimes it happens simultaneously.

MOSCOSO: Zap #4 got busted everywhere. The first edition was 50,000. It sold out in a couple months. Reprints. It was the biggest selling Zap Comix that we had done, and probably did. All the seven were on board for that one. That would probably be the peak for Zap Comix, and then we just kept going. But it got slower and slower, and we didn’t print three comics a year or something like that, but we started going one comic every three years

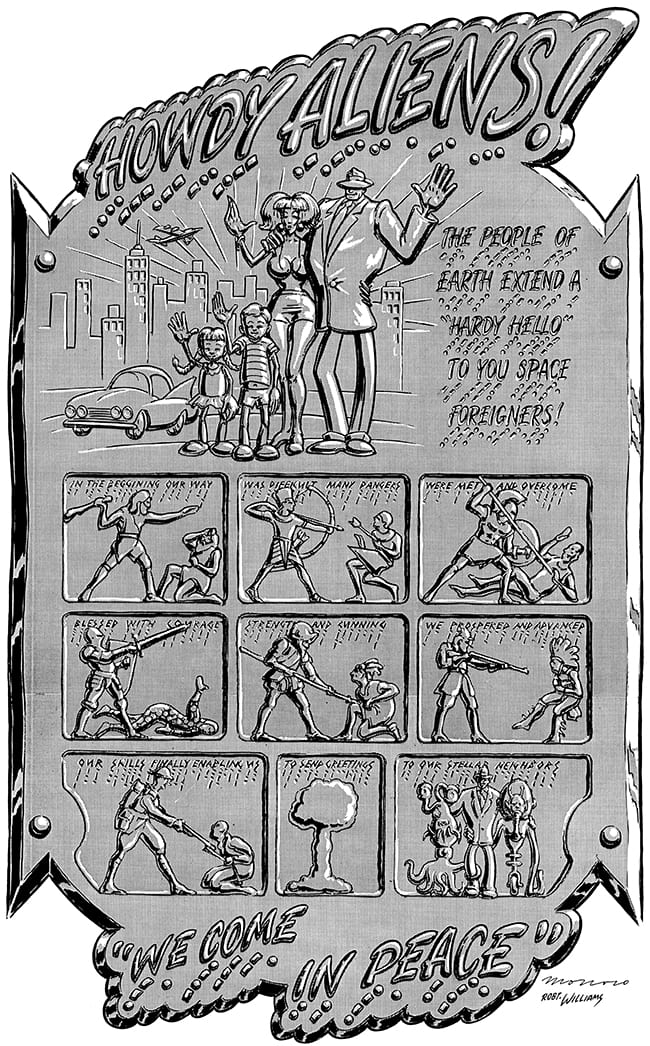

In addition to stomping on societal taboos, Williams and Moscoso and Griffin also wanted to transcend the traditional comic story structure and approach the medium as visual art rather than literature. Crumb and Shelton and Rodriguez were more interested in narrative forms, said Williams.

WILLIAMS: The very first comix were not insistent on an obvious dialogue. They were more expressing a revolutionary insanity, a psychosis, than they were expressing a literal story structure. There was a search for an abstract language in the comics, more than a literal language. So the first couple of issues of Zap we were equal, 50/50. Half of us were storytellers, and half of us were graphic artists. The graphic thing is what died out in the mid-’70s and never really regained itself.

MOSCOSO: Crumb and Wilson were using [Will] Eisner’s technique. The story had a beginning, middle, and an end. Griffin and Moscoso weren’t doing that. Our stories had no beginnings, no middles, and no ends: a non-linear story. That’s interesting. And not only is it interesting, it’s more lifelike. When you get up in the morning, and you go out in the street, you don’t have a linear day. You don’t know who you’re going to run into; you don’t know what they’re going to say; you don’t know how it’s going to end up. What is life? Life is a sequence of one event after another, and Rick and I were much closer to reality in our absurd, non-linear use of the comics form than Wilson and Crumb, who were definitely and obviously lifelike, since they were drawing like life. But really, it’s all marks on paper.

GRIFFIN: Ultimately the form and function of comics is to tell stories. But at that particular time I got involved with the comics because comics were a forum: a forum that was always looked upon as being juvenile and unimportant and insignificant to the general train of art history. The reason I liked creating an art that had the appearance of comics was that it was a throwback to a period of time when I could care less about the status quo or what was acceptable or not acceptable or valid art. It was just pure enjoyment. So I began to do comics. They weren’t really comics. They just looked like comics.

WILSON: I think a comic strip, like jazz, is pretty American. The variations of how much stuff you can cram into a comic strip or how far you can stretch the envelope in a form of music or a comic strip is pretty endless, you’re limited only by your imagination. You get aesthetic debates and nuances of details and shit. But just draw the motherfucker and argue later.