Do you think that's actually changed your work?

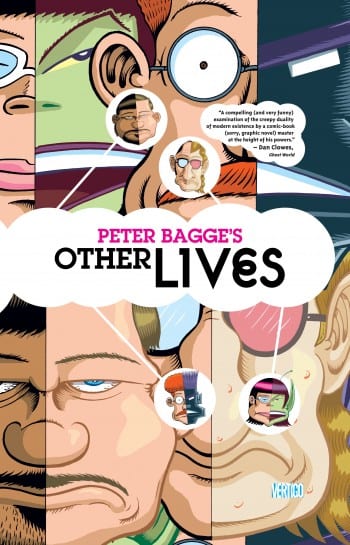

Yeah, because I'm doing big, long stories now. I'm writing graphic novels. I'll still do a short piece for somebody, but for the most part and by default I'm a graphic novelist. The last thing that I did for DC was graphic novel called Other Lives, and they refused to serialize it. They only wanted it to come out as a book, and not come out originally as a miniseries. They said, "We'll just lose money on that, so let's just go straight to hardcover."

How did that work out; do you know?

How did that work out; do you know?

I never asked them how much money it made. What was great for me was that I got a flat page rate, and it was a generous one, too. I signed the contract with them before the recession hit. [Laughs] So what I made off of it compared to what I can squeeze out of people now was pretty phenomenal. Who knows if I'll ever seen money like that again? I hope so, but I certainly haven't seen anything like it since.

Okay. So since we're talking about money, I wanna talk a little bit about the nuts and bolts of actually you making a living at this, starting at the beginning. So you got done with SVA, then you got involved in Punk, right?

Um, yeah. Well, I just went through a whole series of day jobs after I quit art school, and then when I'd come home from these day jobs I'd would try to squeeze in as much drawing as possible. I had a very big learning curve ahead of me, because even though I doodled all my life, I never approached comic art like a professional. I had no prior experience using technical pens, brushes, crow quills, all the professional tools. It used to just be ballpoint pen and Magic Marker on lined notebook paper. And my work was very scratchy then, too. I was so taken with Robert Crumb's artwork that I tried emulate his crosshatching, and I had no idea what I was doing, it just looked like a mess. It took me a while to stop trying to do that,; it became a bad habit. I went back to it years later, but I had a much better idea of what I was doing by then. I also slowly started meeting other cartoonists from all different places. There was this guy, I don't think he does comics anymore, but there was this black guy with dreadlocks who I think used to do comics for Creepy and Eerie, but wound up making jewelry or some such. His name was Buzzy. I wish I could remember his last name. Anyhow, he introduced me to John Holmstrom. I knew Punk magazine and I loved it, and Buzzy figured that Holmstrom and his cohorts would like my work, which they did. But unfortunately Punk went out of business right afterwards, so that was that. I wish it was the first place I'd gotten my work published in, but no such luck. The first place I was ever published was an underground newspaper that didn't pay anything called The East Village Eye. Then I started getting a bit of paying work, mainly through the guys that worked at Punk. Punk's art director, Bruce Carleton, became the art director at Screw magazine, and was later replaced by Ken Weiner (aka Avidor), whom I think you know in Minneapolis...

Yup.

And I used to work pretty regularly for them. Drew Friedman's brother Josh was an editor there as well. Screw didn't pay very well, but at least it was exposure. I was seeing my work in print.

Exposure. Get it? [Laughs] Pornography.

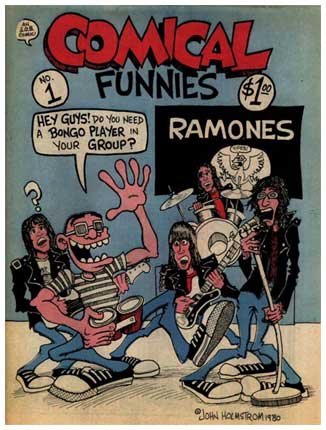

Zing! And then also High Times magazine. Which oddly I recently started doing illustrations for again. At High Times they had an art director who liked my comics and ran as much of it as possible. But then I wanted to do longer pieces, meaning more than two pages. So that's when I, Holmstrom, and a couple of other guys started Comical Funnies. Later on a guy named J.D. King joined, whose art I really loved. We all had a fairly similar sensibility and aesthetic, so we all pooled our resources. We did three issues of Comical Funnies, after which Ken Weiner and I did our own comic book, and that was pretty much it for my self-publishing career. I didn't have the good business sense needed to self-publish, and I felt that everything involved with self-publishing was a huge distraction. You know, dealing with distributors and printers and all of that, I really hated doing all of that. So…

Ooohhh boy.

[Both laugh] I wish I did have a knack for it, because I've known a few other cartoonists who did have a knack for it, and they became millionaires self-publishing their own comics, you know?

Yeah.

Of course it helped that they drew a lot faster than I did too. But I just couldn't do all that juggling.

No, I just made that sound because that's something I work very hard at trying to admit to myself once a week, and it never quite sticks. That I'm a shitty publisher with a terrible business sense. Like I should just draw, but some dumb part of me rears up and says, "No, I wanna put this thing out myself."

You need to see a shrink! [Laughs]

So after that, is that when Neat Stuff started?

Well, by then I had quit my day job. It seemed like not too terrible an idea since I was getting paying work here and there. I was making like five thousand dollars a year, but my wife was doing good managing a restaurant so, with her blessing, I gave it a shot. That allowed me to devote a lot more time to my comics, and I started getting better a lot faster. And by this point Robert Crumb started publishing more of my work in Weirdo, and then he asked me to edit the thing. That was a big thing for me, working with Crumb on Weirdo magazine. It barely paid, but it was a great opportunity. It was also around that time I had met Gary Groth and Kim Thompson, who prior to that I knew simply as the guys who did The Comics Journal. I loved the Journal. I couldn't believe what wise-asses those guys were.

[Laughs] Yeah.

But then around that time they started publishing comics. I'd seen Love and Rockets; I might not have even realized that Fantagraphics also was The Comics Journal. But I also knew a cartoonist named Milton Knight, who did a funny animal comic called Hugo, which was being published by Fantagraphics. They were in Connecticut, which was just a one-hour drive from where I lived, and he said, "You should definitely go see those guys." When I met them, I showed them samples of my work, and I wasn't there looking for my own comic book -- I wanted to talk to them about doing an anthology for children, actually. Like a kiddy version of Weirdo, of all things, which they wisely passed on. Instead they said to me, "Would you like to have your own comic book published by us?" Which was my dream. I was like, "Oh yeah, that's fantastic." But between us agreeing to do that and it actually happening there was a big break, because in the meantime I moved to Seattle and they relocated to Los Angeles, and it took them a while to get set up there. So once we were both settled out west we started talking about it again, and that's how Neat Stuff got started. That would have been 1984, 1985, something like that. And I had every intention of continuing to edit Weirdo and do Neat Stuff, but Neat Stuff was my own comic book, so it meant everything to me. I wanted to make the absolute most of it, and by doing that it started cutting into how much time I could devote to Weirdo, so I felt like Weirdo was suffering because of it. So even though Crumb wasn't happy about it, I had no choice but to quit. Basically, Weirdo could continue without me, but Neat Stuff was all me, so if it a was going to be one or the other I had to give up Weirdo. Fortunately Weirdo was able to keep going because-

Aline took it.

Yes. Prior to that the Crumbs had a toddler, but by the time I asked them if I could drop it, their daughter Sophie was already in school. So that gave Aline time to concentrate on it, and she did a great job.

Yeah. Can we just pause for a sec- I mean, you agree, right? That Weirdo's maybe the best magazine of all time, right?

Well, I think it's the best comic anthology of all time, sure. Other than maybe the original MAD[Laughs] if you count that as an anthology. But sure, within the world of underground and alternative comics, I would agree with that. The reason that I'm so reluctant to say it is because not many people agree. It's so forgotten about, it's so overlooked, and we were always being unfavorably compared to Raw in particular.

Can I hit you with my theory?

Go ahead, sure.

Here's my theory, and I am behind you by a decade or something, but I feel like, when I was growing up — you know this thing that comics has developed into now, which came from the fight for comics to gain some kind of respect as an art form. Comics were not taken seriously, so there was this big push, this big fight to have it be not just juvenile nonsense, and various people were pushing that forward in a lot of different ways. And I think Raw was on one end of that, but Raw was one take on that, and that was..

They were on the forefront of that.

They were at the forefront, but if we're talking about two sides of the coin, one being Raw, one being Weirdo. And the Raw side of the coin was-- it was more SoHo. It was Art World. You know what I mean?

Your theory is more than a theory, it's the truth. [Laughs]

And Weirdo was like this magazine that- and to me it extended beyond comics, because the greatest thing about Weirdo was it felt like the people who read Weirdo weren't like- it was a lot of comics people, certainly, but beyond that it was a bunch of people who actually were just weirdos. You know, who came from-

That was particularly true when Robert Crumb was editing it. He just looked for the most mental, deranged, utterly unselfconscious work he could find. He published work that was literally created by mental patients. I tried to keep the spirit of that going, but -- well, maybe it was because of my youth or just my own sensibility, but people always pointed out that the issues I edited tended to be a bit puerile. [Laughs] Lots of puke and farts and zits.

[Laughs] Did I ever tell you the story about my car dying?

No. I don't think so.

It was when I was living in Duluth, and I was in the band. The band got some kind of advance for something, and I bought a Subaru, and it was a piece of shit. It was a lemon. And I drove this thing into the ground, and it started spewing black smoke, and I mean it was going to explode. I couldn't find anyone in the Duluth area who would come and pick it up, you know, anyone who would come and tow the thing away for free. I was going to have to pay to get this thing to the junk yard, and I was like, "I am not putting another ten dollars into this car." So I finally found one place, who said, "You get it here and we won't charge you, we'll take it for free." So I had my friend Jesse follow me in the car, because it was shuddering, making terrible noises, all that-- the place was about thirty miles out of Duluth or something. The car just barely made it in there, and kind of just died on the spot, as soon as we pulled up. And I went inside, and it was this kind of woodsy area and it was just a really weird place. So I went inside and I started dealing with the counter guy, and he was like, "Yeah, we'll take your piece of shit, whatever." I started looking around and on the walls around me were these drawings, and I was like, "I know these, why do I know these drawings?" They were all over the place, and I was like, "Why do I- they're so weird, why do I know these drawings?" So I asked the counter guy, this big bearded guy, "Who drew these?" And he was like, "Oh, it's just some weirdo who just lives out in the woods." And then figured it out and-- Oh my God, that's it! Crumb published those in Weirdo. And it's-

Yeah, Fantagraphics put out a book collection of his work. Norman Pettingill!

So I turned to these mechanics at the junkyard and I was like, "This dude's famous!"

[Laughs]

Like, "Don't you understand? He's been in Weirdo magazine, don't you guys understand?!" And they are all looking at me like I'm nuts. "Listen kid, he's just some weirdo who lives out in the woods."

Right. [Laughs] They were right and you were wrong!

But back to my big theory, I think the way that things have played out now, is for a while there were the children of Raw and the children of Weirdo, and there was crossover there-

Yeah, especially over time. Both magazines continued all through the '80s, and by the time Aline was editing it, it was pretty much straight comic story-telling narratives. Very much worked from a unique personal perspective, not as wacky-crazy as it was earlier. And Raw also switched to this thick digest-sized format, and because of that the nature of it became much more narrative-driven as well. It was no longer an art gallery you held in your hand, it was about the stories. And by that point a lot of the same artists were appearing in both publications, like Crumb himself, and Drew Friedman and Kaz. It's funny, they started out these two polar opposites, but after ten years the two publications had a very similar aesthetic and sensibility.

You know, I actually hadn't thought about those digest issues. When I think about those big oversize issues, those things where like a gallery piece. But those digest things were a lot closer to Weirdo than Weirdo was to Raw. My big theory is that those two were the big camps, and right now it feels like Raw won. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yes, they did. And you know, it gave comic artists a lot more options. Now we have a much easier time getting teaching jobs.

Yeah, I've heard of people like that. [Laughs]

And you have a lot more comic art shows, and in a lot of ways it's good not to have to apologize for being a cartoonist. Options are good. Actually, all things considered, it's been great.

That's not what I wanted you to say, Pete. Come on!

But the stuff that we were talking about that we miss, it's really hard to pull that off. You're just immediately ostracizing yourself. You'll be automatically alienated by merely doing a comic book, and filling it up with stuff that is making no attempt to be important or profound. Work like that used to be very common, but now you'd have a hard time finding someone who would publish it. Who would buy it, besides a hand full of kooks like Jason Miles? [Laughs] I think it's utterly non-viable. The last thing I can think of that totally fits that description was Johnny Ryan's Angry Youth comics, and even he stopped working in that format. It just didn't pay enough.

Yeah.

It also would feel like I'd be starting from scratch. I'm going back to square one, but when I was originally at square one, I didn't have a mortgage or a kid in college. I had nothing to lose back then. Now I do!

[Laughs] That's my bone to pick, I feel like there was this shift. And again, everything you said is absolutely true, and we are- through teaching, whatever- we're seeing the benefits of not having to apologize for comics anymore.

Social acceptance. [Laughs] We're not pariahs anymore.

Yeah, but I kind of miss that. This is were I feel that personally, how I feel about the Sammy the Mouse thing, with my own comics. It took me a long time to figure out what type of comics I felt comfortable doing, and it was really convoluted getting there, but the Sammy the Mouse stuff feels like these are the comics I'm supposed to do. And I feel like, the interesting part about me getting there, finally, is that at this particular time in comics, it just so happens that doing what I'm doing is one of the most uncool things you can be doing.

Within the world of comics or just in general?

[Both laugh] Within the world of comics. I think, you know, the work I was doing ten years ago, when that perceived seriousness was a concern of mine, where I thought, "I want this to be taken seriously. I take it very seriously and that's how I want it to be received," and that was a concern of mine—and that's not to say I take it any less seriously now. I just now feel like I'm gonna do what I do and people can make whatever they want out of that, but I'm going to be as stupid or as goofy as I feel like being, regardless. Which I think is the same for you-

Right.

It's just the kind of comics I'm making right now, they're not the type of thing people are standing up and paying attention to. And that's not even the right word that I'm looking for. Do you know-

No, I know exactly what you're talking bout. When I first got into the comics field, first as self-publishing and then later on with all the work I did with Fantagraphics, it was always this huge uphill battle to get comic shops to carry my stuff, or to carry anything that was like my work. Because the comic shops were dominated by superhero comics, and they were owned and run by guys who liked that stuff, and who didn't like the type of work that I did. It was very hard to find comic shops where the proprietor truly liked what I was doing. At a certain point with the advent of graphic novels and the switch to the book format, we seemed to have an easier time with bookstore owners than we did with comic shop owners. They seem to be more receptive to what someone like Fantagraphics was doing. But then came the advent of all these CGI-based superhero comics, and video games, which are also are getting more and more elaborate and they're also very action-adventure genre. So because of the exciting new technology, superheroes and that action genre stuff is more popular than ever. It dominates more than ever. I find it very depressing, although at this point I don't fight it, and I even try don't think about it, but it's amazing how superheroes and comic art have become more synonymous than ever.

The comics aren't selling anymore, it's the movies that are selling.

I occasionally teach a comics writing class, and most of the boys, that's all they really want to write about. With ninety percent of my students, this is the first time they've ever seen comic art that wasn't manga or action-adventure genre. They think they're advanced if they're familiar with Hellboy or Vertigo titles.

Wait. What age are you teaching again, Pete?

Oh, college.

See, that's so weird because on the whole, my students aren't really what you just described--

Well, you teach at an art school. I don't know if that makes any difference. I teach at a regular four-year private college, Seattle University, and these are English majors. So who knows? They might be reading very serious print novels, but when it comes to comics, the girls were weaned on manga and the boys have one foot, if not both feet, firmly planted in superherodom.

Yeah, that's strange to me. I don't find that with my students all that much. But yeah, I don't know where the middle ground is. The thing that's annoying to me- And I want to back up and say that that thing I said about Sammy, about that being a very uncool thing to be doing right now, I want to say that I truly do not give a fuck.

Oh okay, well that's because you've got your day job. [Laughs]

No, I mean, it's because I like what I'm doing. You know I'm lucky enough to-

I know, I was insanely ambitious for a long time. The whole time I was doing Hate, I was just pushing like crazy to sell as many units as possible. I was doing everything I could to maximize the earning potential of doing an alternative comic book. I guess I achieved it, but I had no choice but to stop caring once I realized that I hit a wall. Years were going by and I was like, "This seems to be as good as I'll ever do," and already I could see from the shift to graphic novels that comics like Hate were going to go the way of the dinosaur. I kept trying to brainstorm with Fantagraphics, trying to come up with ways to keep it going as a periodical and keep it economically viable, but they were quickly losing interest. It seemed so obvious to them to go the graphic novel route, and it was the path of least resistance, and what I was suggesting we do was completely outside of that. So I just dropped the idea. Hate was sort of evolving into an anthology at the end, and I wanted to expand on that. But it just seemed like a big headache to them. It's bad enough when you're fighting the market, but when you're fighting your own publisher— [Laughs] I could have done it with a different publisher, but I didn't know of anyone offhand that would seem to be totally receptive to such an idea.

I think that there is now a prejudice against comics that are entertaining.

[Laughs]

Do you agree with me or not? [Laughs]

Well, define "entertaining." Whatever is selling somebody must find it entertaining.

I don't know if I believe that, do you?

Yeah, of course. There was a period where I was making fun of this main thread that alternative comics took. There got to be this real samey-ness. I used to call it "falling leaf comics."

[Laughs]

Where you have to turn eight pages before you got to a title or any dialogue, and you'd just be looking at somebody's feet walking through mud puddles. The strange thing though, not just with those particular comics that I'm talking about, but with alternative comics in general, is that whenever you name a specific artist, chances are I'll like that artist. So I'd belly-ache about certain tendencies, but whenever somebody starts throwing names at me, 99% of the time I'll say, "Oh yeah, he or she is pretty good." So I have a really hard time singling out any one person. Even if I did single out a single person who epitomized that, it still doesn't mean that I think that person is no good. In fact, there's more good artists now then there's ever been.

I totally agree, but--

It probably has a lot to do with my age, I've gotten jaded and I feel like I've seen it all. I rarely see something that knocks me out, whereas it seemed like all through the eighties and early nineties, I was regularly seeing work that struck me as original. Alternative artists' art styles back then generally were much more distinctive. Everybody had a much more unique style -- not just a drawing style but their whole approach, the approach to storytelling, even formats. Back when almost everyone was self-publishing, the formats were wildly different. So you couldn't begin to compare the artwork of Chester Brown to, say, Lynda Barry, or the Hernandez brothers or Charles Burns or Gary Panter, Mary Fleener. You know what I mean?

Yeah.

But by the late nineties, this samey-ness took over. Both in drawing style and in story telling, just in the way people constructed stories, and formatting. More recently it seems people trying to fight their way out of that. But for a long time it was all these pouty auto-bio sob stories -- the whole thing all about how your girlfriend doesn't understand you and then breaks up with you, and you feel really lame and then some other bad thing happens, though by the end you come to some lame realization that you could be worse off. [Laughs] "Thank goodness for porn!" The end.

(continued)