In his “manga columns” (manga koramu) from 2005, Natsume Fusasnosuke returns to his trademark formal analysis of the shōjo manga style, applying it to Yoshinaga Fumi, author of award-winning manga such as Ōoku: The Inner Chambers (2004-2020). Natsume here discusses the kind of panel “beats” (ma) and “white break space” (mahaku) which he sees as being two important components of panel configurations in shōjo manga. For Yoshinaga, such techniques are crucial for the type of humor and pathos she produces in her otherwise restrained stories. Originally, Natsume outlined these shōjo manga characteristics in his seminal contribution to the co-authored Manga no yomikata (How to Read Manga) (Takarajimasha, 1995), and he further discussed ma and mahaku in his near-final chapter of Manga wa naze omoshiroi no ka: sono hyōgen to bunpō (Why Is Manga So Interesting?: Its Expression and Grammar) (NHK Library, 1997), which is now available in English via our translation of “Panel Configurations in Shōjo Manga” in U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal Vol. 58 (2020). In his succinct essay here on Yoshinaga, Natsume applies his trademark tools, created a decade earlier, to look at this contemporary artist and her bold, new approach to the shōjo style. He describes how Yoshinaga makes her manga interesting (omoshiroi), for example, by having either dryly humorous scenes or grim, tragic moments stretch across two-page spreads with surprisingly successful results.

Although some might simply describe her manga humor as dry and unfunny, Natsume goes on to consider how “gallant” or “graceful” (isagiyoi) Yoshinaga makes girls’ comics that defy gendered stereotypes by having female characters who often behave in extremely rational ways—and, vice-versa, male characters who defy type by acting irrationally and fully revealing their feelings. Such characters abound in Yoshinaga's masterwork series, Ōoku, which had the last installment of its 19-volume series appear in the December 28, 2020 issue of the monthly magazine Melody (February 2021 cover date). Dr. Hikari Hori, writing in 2012 about the beginning of the series, went further than Natsume does, arguing that Yoshinaga’s manga “overturns and interrogates popular gender discourses” and “demonstrates the potential of feminist authorship in the practice of deconstructive storytelling” (“Views from Elsewhere: Female Shoguns in Yoshinaga Fumi's Ōoku and Their Precursors in Japanese Popular Culture”). And yet, what Natsume does in this essay is to concretely isolate those Yoshinaga traits, or, the “expression and grammar” that he sees in her works—placing her style in his larger theoretical approach of “formal expression” (hyōgen-ron). Seemingly contradictory, Yoshinaga blends a shōjo manga panel configuration style with a “gallant” and “dry” sense of pathos, thereby allowing her to create a new kind of feminist and critical commentary on gender in her comics.

We thank Natsume-sensei for his continued permission to translate and publish his work in The Comics Journal.

–Jon Holt and Teppei Fukuda, translators

* * *

“Yoshinaga Fumi: Isagiyoi shōjo manga”

from Manga wa ima dō natte oru no ka? (What’s Happening in Manga These Days?), Media Select, 2005

I came to read Yoshinaga Fumi through fellow manga researcher Ms. Yamada Tomoko, who loaned me her books. I also watched the adapted television drama Western Antique Bakery (Seiyō kottō yōgashi ten)1 and read the original Yoshinaga manga. I cannot remember who or what got to me first.

Either way, I felt that Yoshinaga has an exquisite skill to make humor through the handling of sublime moments of time.

She creates these amazing beats (ma) where the scene takes a big leap, often just through a depiction of a character’s facial expression, when the panel simply becomes white space with nearly all scenery omitted and it seems like things are barely moving at all. It is the kind of subtlety that must be difficult for comic readers uninitiated in this kind of manga grammar. For me, it kind of hits the spot.

There are people who can tell a joke without any kind of facial expression. I am probably one such person. But these kind of “jokes” (warai) only work if somebody catches what you throw at them. Humor like this needs a bit of time to pass and then the listener suddenly starts snickering. The joke lands its mark but there is always a time lag.

Yoshinaga’s “jokes” then are this kind, that take time to get.

Even so, it gradually dawned on me that she is not just an artist who effectively can use beats (ma) for jokes.

I reckon that it might also have something to do with Yoshinaga being a shy person.

For example, in her 1998-99 manga Garden Dreams (Kare wa hanazono de yume o miru [serialized in Wings and collected in a one-volume paperback]),2 she opens her story set in medieval Europe with a single page (tobira-e) only containing this stark caption: “In my entire life, I have known true love only twice.”3

A lord is deprived of his lady-love by a violent rogue. His lost love has an older sister. The lord takes as his new bride this woman, who is gloomy and lifeless like a stone. Over time, though, the lord slowly realizes her gentle side, and one day he confesses to her “I love you,” wishing that she will save him from his loneliness.

It is the first time that they are bound together by love. After that time, he also confesses that, in fact, at first he was to be engaged to her—the older sister—but because he had fallen madly in love with the younger sister when he encountered her, he changed his mind to be engaged to the younger of the two.

“Isabelle died never knowing any of this. I'm sure you didn't either, or how could you ever be so calm--”

Speaking thus to her, the lord looks at his new bride’s face and he realizes that in fact she knew it all the whole time.

“You knew...?!” he asks.

“Yes.”

English translation: Garden Dreams, Sachiko Sato (DMP Digital Manga Publishing, 2007), pp. 96-97.

This entire exchange takes place across a full two-page spread (mi-hiraki) with five panels neatly lined up that consist of only facial expressions and bust-sized shots. Four of those panels merely have white background and one has a voided black background.

In the pages that follow, the lord becomes overwhelmed by doubt for a moment, wondering if the older sister perhaps did kill the younger sister. His doubt fades, but the older sister—the lord’s wife now—learns that he did have this doubt. Now a tear forms on her sad face. Then, without another word, she throws her body off the castle tower.

In the scenes that follow the one where the wife leaps away, we see only panels of the castle’s stone windows, of the face of the lord, and one shot where there is only her trailing black hair (Figure 2). The feeling is tranquil as the author restrains herself from showing anything more here. In the aftermath, Yoshinaga overlaps the lord’s inner speech narration as he reminisces:

“Our love ended the instant I had doubted her.” In the next panel, he adds: “In my entire life, I have known true love but twice…”

English translation: Garden Dreams, Sachiko Sato (DMP Digital Manga Publishing, 2007), pp. 106-107.

To depict the tragedy of a man who had found and lost true love twice, Yoshinaga cuts the scenes using white panels of the lord’s interior monologue as well as many panels of white space (yohaku), often without any touch of scenery. The feeling of these white-panel beats (ma) has much in common with how Yoshinaga will ply her kind of humor in manga.

Yoshinaga draws the despair and clumsy kindness of this stone-like woman and she does so with, at first glance, fastidiously neat panel layouts and pictures, where any excess elements are utterly dispensed with. Some readers might even object that these panel layouts and pictures are too curt and simple. I feel that we can see Yoshinaga’s shyness and self-consciousness from her expressions like this.

All My Darling Daughters (Ai subeki musume-tachi, which ran from 2002-03 in Melody, published in a trade paperback by Hakusensha) at first glance might seem like a short story collection of episodes without much connection to each other. However, it is actually a tightly-interwoven story that runs backwards, starting with a mother and daughter’s story, then shifting to a friend’s tale of the mother’s young husband, next to that of the daughter’s classmate, and finally the story of the mother and the mother’s mother (the grandmother).

Were it a normal novel, the author would make the narrator of the episodes be one person, like the first daughter, so that the whole work would have unified narration. That way probably would have made it easier for readers to understand.

What Yoshinaga does is change up the narrator in each episode. Starting with the first tale, she moves from the perspective of the daughter; in the second, we see things through the eyes of the friend of the mother’s husband; then, in the third story, we understand things from the daughter’s classmate.4 She creates the subjectivities of each of these completely different characters at their different points in their lives, so if we do not read the manga carefully it becomes quite difficult to make sense of the connections these people have with each other.

Thus, the protagonists in each story take life paths that greatly differ from each other’s. And then, these other main characters (in each episode in which they are not the protagonists) only end up existing later as supporting characters. They tend to fade into the background when it is not their turn as a protagonist.

Having already established this point of view with its very detached sense of space, Yoshinaga then at the end of the manga brings us to the daughter Yukiko’s version of the story (as she knows it) of her mother Mari and her grandmother. What this does is allow Yoshinaga to create a device for us to understand the “sins” (or: karma) her grandmother passed on to her mother Mari against the backdrop of the protagonists of the first story (the mother Mari and her daughter Yukiko). In one sense, Yoshinaga gives the readers an exit for the kind of mother-daughter puzzle that has been unravelling slowly through the volume.

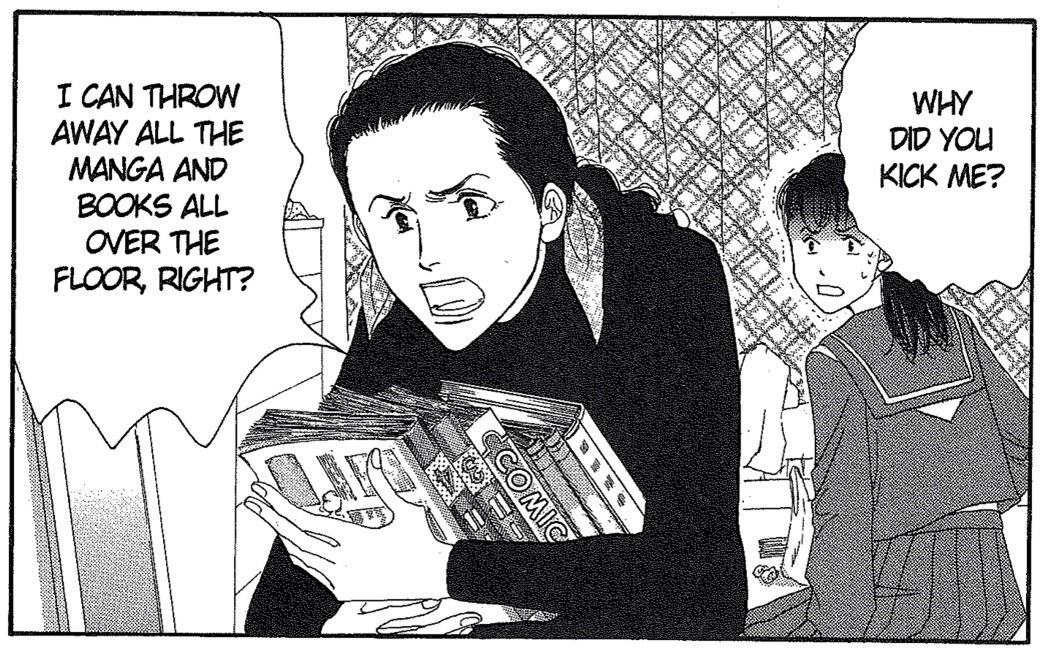

Yukiko seems to us as a kind of charmless, hardened daughter type, and since she does not clean up after herself, she is often scolded by her mother Mari and even ends up on the receiving end of much fussing from a guy with whom she lives. On the other hand, Mari takes out her anger on her high-school-aged daughter. Even at one point when Yukiko fights back, telling her, “Why?! Why do you always have to be like this?! You're just taking out your frustration on me!” the mother retorts, “You're right. That's exactly what I'm doing! And what's wrong with that?”

“Parents are human,” Mari tells her daughter. “Sometimes they have bad moods! If you think everything is always going to be fair, then you're greatly mistaken!” (Figure 3.)

English translation: All My Darling Daughters, John Werry (VIZ, 2010), p. 10.

You will find this kind of gutsy form of acceptance running through the heart of any Yoshinaga manga. That defiant look on the face of Mari, the mother, is so gallant, so cool. There is something so fresh and straight-forward (take o watta yōna) in the way these panels are cut. We can see Yoshinaga’s aesthetics I discussed above in this panel arrangement.

Mari gets cancer but she recovers from it. Not only does she come back with a new zest for life, she even re-marries, taking up with a man younger than her own daughter. Despite all that, she still has an inferiority complex for thinking herself unattractive. Mari is that way because, as she was growing up, her mother always told her she was ugly.

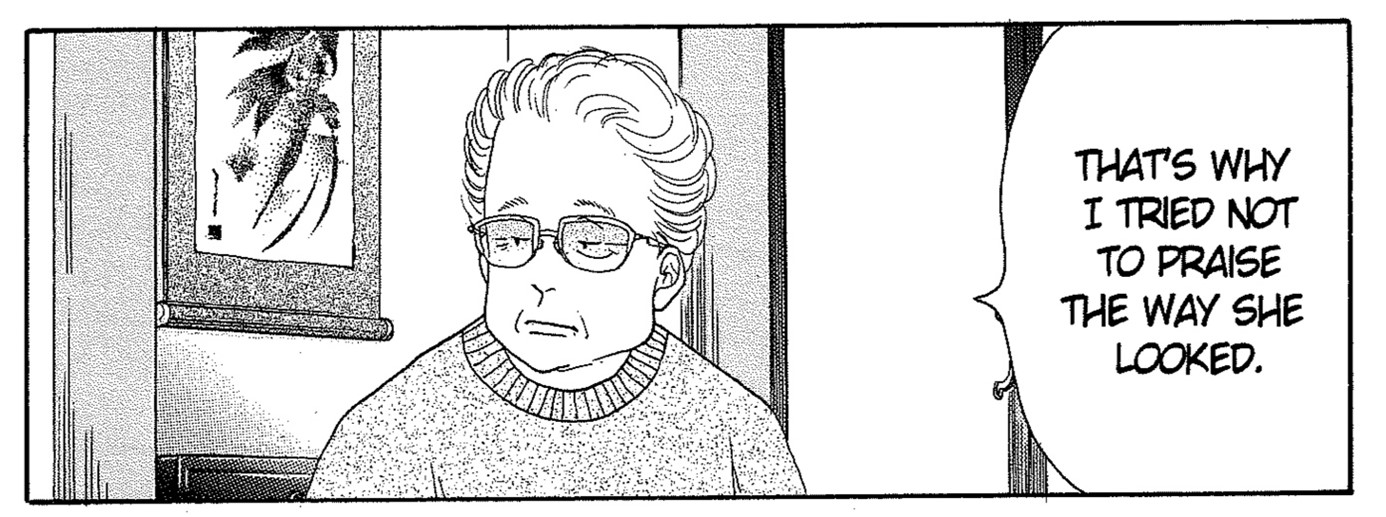

In reality, Mari is quite a beautiful lady. In the end, she never tries to reconcile things with her own mother. In the manga’s final story, Mari’s own daughter Yukiko listens to her grandmother about the reason why she still belittles Mari after all these years.

The grandmother explains that as young girl she had a female classmate who was proud of her beauty and always hurt others so easily for not being equal to her, so when Mari was a little girl and noticed her own good looks, her mother [the grandmother] then treated Mari in such a mean way so that she would never turn out like her vain classmate, even to the point where [Mari’s mother] never would praise Mari for her beauty. The look of the grandmother as she says this (Figure 4) is rendered so skillfully. Her face is truly terrifying.

English translation: All My Darling Daughters, John Werry (VIZ, 2010), p. 198.

Then, Yukiko [the granddaughter] thinks:

“A mother is an imperfect woman.”

Even now Yoshinaga continues to create works like these two examples. Manga really can be so interesting like this. If somebody of my acquaintance didn’t know of Yoshinaga, and was one of those people who says “manga today just doesn’t do it for me,” then I'd want to tell that person about her, begging them, “Come on, at least give comics one more chance and try to read something by Yoshinaga Fumi.”

* * *

- The television show ran as a limited series from October through December 2001 on Fuji Television but broadcast with the slightly altered title (in Japanese) Antiiku: Seiyō kottō yōgashi ten. The original manga was serially published in Wings magazine (Shinshokan) from 1999 to 2002 and has been collected in trade paperback in four volumes.

- TRANSLATORS' NOTE: Kare wa hanazono de yume o miru is the title work of a four-story collection. This volume has been translated into English and is available as Garden Dreams from Digital Manga Publishing.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: At risk of belaboring the obvious, in the original Japanese text of this essay, Natsume quotes from Japanese-language editions of Yoshinaga's comics. Here, we have employed the English translations of those quotes as they appear on the pages of the licensed North American releases of the relevant books.

- The same approach is used in her Kodomo no taion (The Body Temperature of the Kids, [Shinshokan 1998]).