“Is Dan O'Neill our age or older?” Adele said.

“Older?” I said.

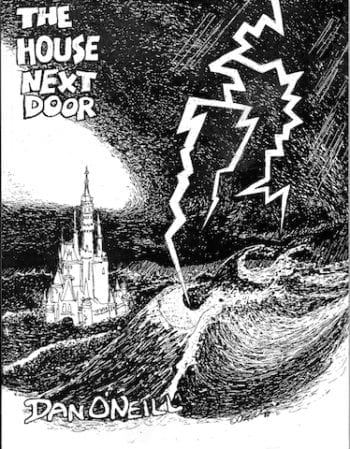

“Well, he’s still got all his marbles,” she said. “Or as many as he ever had.” The occasion for these remarks was our receipt of his first book in thirty years, The House Next Door (Hugh O'Neill & Assoc.). “It’s the first time I’ve understood the relationship between gold and money.”

“You understand it?”

It is part of Adele’s charm that I generally must identify for her who the person is that has outraged Stephanie Ruhle that morning. She returns the favor by identifying for me each Czech teenager who had made the quarterfinals of the tennis tournament of the week.

It is part of Adele’s charm that I generally must identify for her who the person is that has outraged Stephanie Ruhle that morning. She returns the favor by identifying for me each Czech teenager who had made the quarterfinals of the tennis tournament of the week.

“Gold. Money. Corporations. The environment. It’s bigger than his fight with Disney.”

To answer the most frequently asked question by people who have read my saga of this fight (The Pirates and the Mouse (Fantagraphics)) but have not kept up with O'Neill since: “No, he isn’t dead.” The rootin’, tootin’ embodiment of outlaw cartoonist, whose Odd Bodkins was the first syndicated strip to oppose the Vietnam war and champion drugs, who besides standing up to the Disney Death Star, rode with the Mitchell Brothers against Dianne Feinstein, dropped in on Wounded Knee and Belfast, and egged the Queen of England’s flagship, still lives in Nevada City. He has contributed to fringe publications here and there, The Anderson Valley Advertiser, Berkeley Daily Planet, and Downieville’s Mountain Messenger, for three. He has had his personal papers collected by the University of California. He is prepared to relaunch Odd Bodkins “in whatever newspaper has the nerve to print it.” And in a bit of real life surrealism that makes Salvador Dalí's watches look like they were manufactured by Timex, he has served on the board of directors of America’s oldest gold mine.

This last experience shapes his book. Write (and/or draw) what you know is a useful instructive, especially when you mince this knowledge with a consciousness as outrageous, original, and damned funny as O’Neill’s.

Except for a brief excursion down a mine shaft, most of House Next Door takes place within “The End of the Trail Saloon,” a teetering-on-cliff's-edge establishment familiar to readers of O’Neill. And most of this action consists of two parallel (but ultimately converging) conversations. The first is between O’Neill and his old pal Abraham Lincoln (with whom he has been chatting, at least in comic form, for a half-century). They are later joined by Marcus Aurelius, Abe’s sponsor in a Being-Dead group, which deals with the difficulty of adjusting to eternity, and Philip of Macedon (“Phil! Over here.”), who shares the others’ interest in affairs of state. The second is between Al, the bartender, and Smokey the Bear. (There is musical accompaniment by a 12-inch-tall pianist sitting in for Bill the Horse, who usually tickles O’Neill’s ivories.)

The focus of O’Neill group’s conversation is the importance of gold to nations. (At this point, for those of you wish to judge my recapitulation of this discussion, I should point out that (a) I struggled to attain a C- in Economics 1A, and (b) if Diogenes, while searching for his honest man, had cast his lantern on O’Neill, he might have been greatly entertained by the blarney, but he probably would have kept going.)

The focus of O’Neill group’s conversation is the importance of gold to nations. (At this point, for those of you wish to judge my recapitulation of this discussion, I should point out that (a) I struggled to attain a C- in Economics 1A, and (b) if Diogenes, while searching for his honest man, had cast his lantern on O’Neill, he might have been greatly entertained by the blarney, but he probably would have kept going.)

Anyway, as I understand it, the idea is that nations need gold to pay armies to defend and/or advance their interests. (O’Neill makes clear why, due to perishability, pork bellies would not work as well, but his explanation, it seems to me, does not rule out mustard pretzels.) The USA, he says, had 65 percent of the world’s gold as recently as 1945, but now has “none,” except for that “in granny’s teeth.” Our dependence on oil has set most of it “riding around somewhere on a camel,” leaving us “hostage to” a “mutant form of Islam... [that has] been gunning for us [since]... before we existed. [...] No gold means... it’s over. No social justice. No liberty and goodby to love thy neighbor.”

Figuring in this bleakness somehow, like raisins in oatmeal, are Alexander (“The Little Pimp”) Hamilton, Andrew Jackson, Karl (and Groucho) Marx, J.P. Morgan, the Rothschilds, and an O’Neill-ized enemies list of “Texas oil,... Wall Street, and the Limeys.” O’Neill, I would venture to say, is a bit of an American exceptionalist. He favors baseball, blue jeans, and rock ’n’ roll. Also gay marriage, a woman’s right to choose, immigrants (“the larvae stage of Americans”), and, above all, the First Amendment. He honors the country, or at least the values it sometimes espouses, above most of the human race, whose “favorite form of government” is “tyranny” and whose history reveals “a chaldron of greed, social injustice, and racism.”

Eventually this brings O’Neill to float his wish to get the USA off oil – and into fuel made from grass cuttings. “Independence,” he writes, “is me blazing down the freeway in my 1951 Studebaker with the 1954 Corvette engine running on alcohol made from my front lawn.”

Which brings in Smokey.

An expert on “woodsy stuff,” he reports the existence of a “biomass” of wasted energy, 100 million dead trees stretching from Oregon to Mexico, making the Sierra Mountains “the Saudi Arabia of cellelose [sic] energy.” And once he joins the Table of Four, a plan emerges.

California should take the $4 billion/year it spends fighting forest fires and build forty plants ($90 million apiece) and pay 80,000 unemployed loggers ($50,000 each) to cut down the combustible dead trees and surrounding brush and haul them to the plants, which will convert them into 470,000 tons of energy-rich “black pellets” annually. These pellets will free the United States from its dependence on oil and — sold to China — free it from burning the coal which is killing four thousand people daily. They will be sold for $45/ton, raising over $21 million/year for the state to spend on infrastructure and education. (Build 2000 plants, says O’Neill, you replace 193 million tons of coal. Build 4000; you end global warning.)

California should take the $4 billion/year it spends fighting forest fires and build forty plants ($90 million apiece) and pay 80,000 unemployed loggers ($50,000 each) to cut down the combustible dead trees and surrounding brush and haul them to the plants, which will convert them into 470,000 tons of energy-rich “black pellets” annually. These pellets will free the United States from its dependence on oil and — sold to China — free it from burning the coal which is killing four thousand people daily. They will be sold for $45/ton, raising over $21 million/year for the state to spend on infrastructure and education. (Build 2000 plants, says O’Neill, you replace 193 million tons of coal. Build 4000; you end global warning.)

According to a recent New Yorker article, the United States “can produce 1.3 billion tons of dry biomass” from grasses, corn stalks, and trees, which would convert into a hundred billion gallons of biofuel, reducing auto emissions by over 85 percent. So O’Neill is not entirely talking through his miner’s hat. But even this C- student can spot some problems. That $4 billion saved from fighting fires is spent twice the first year, isn’t it? Arthur Anderson may want to vet some of these other numbers, and the EPA may want an environmental impact report on the plants.

Oh yes, the plants. How the corn stalks are converted into pellets is not explained.1 And the entire project seems to depend on a renewable supply of trees and brush, which, as far as I can see, depends on rivers being cleaned, thus enabling salmon to return, whom bears will eat, leading to a continual fertilization of the forest floor, since, as Smokey says, “Shit happens.”

I will leave the math and science to better minds. I’m just glad O’Neill is back and crackling.

He has always been a cartoonist for whom the verbal component is paramount. Fifty words a panel, a hundred, two hundred is nothing. Some panels are completely text. (You get the idea O’Neill would not be cartooning if he had to be silent.) And given the dimensions of his book (8 ½" X 11") and its formatting (two to four panels per page), he needn’t edit himself toward muteness or scrunch his words into a font beyond the capacity of all but the raptor-visioned.

O’Neill seems incapable of looking at history – or out his front door – without being engaged (or enraged) by it. But his fulminations, feuds, and furies all come with stinging humor. Here are a few of my favorite one- (and two-) liners, context supplied when needed, from this book:

1. The lull between WW I and WW II was necessary to give “the fat and stupid that didn’t get killed [time to] start breeding.”

2. “Gold is the only substance in this part of the universe that doesn’t... oxidize!! We oxidize only we call it birthdays.”

3. As polar ice melts, seals vanish, so polar bears hunt indigenous people. Therefore... “Global warming causes an acute shortage of Eskimoes.”

4. Protestantism is "a religion started by a 15th century English king over where he couldn’t put his penis.” And...

5. ...since for Protestants proof of God’s love is the amount of “stuff” one acquires, “Fear of damnation causes shopping.”

The visual component of O’Neill’s work suits the verbal well. It is representational enough to connect his words to the world but sufficiently askew to make clear this is not a government position paper. In other words, there is reality—the state is burning, the planet is collapsing—but there is room, and perhaps a need, for nonsense. I mean, a talking bear, a 12-inch piano man singing, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” But where have logical argument and science-based evidence gotten us anyway, besides dangling on a cliff’s edge like the Last Chance?

Everything is black-and-white. (In art, as in life, O’Neill is not much for shades of grey.)

He is, though, playful. He voices the crisis at hand through goofy-eyed, pliant-bodied characters, an attempt at snagging flies through honey, not vinegar. While their dialogue proceeds forward sequentially in time, illustrations may flip back centuries to capture a just-expressed point of reference or to dramatize a metaphor that has just appeared within a word balloon or caption.

O’Neill’s line, not unlike his thinking, may wobble, but it also charms as it argues. There is a “roughness” to his art, a “scratchiness,” which tickles while it irritates. It has an aspect of – I donno – “primitiveness,” like a cave drawing from an eclectically read and eccentrically schooled subterranean consignee. But may not that be a good way for a creator to go? Lock himself – or his vision – away. Feed it with what comes to hand. Pat its head. Cuddle it. Let it grow.

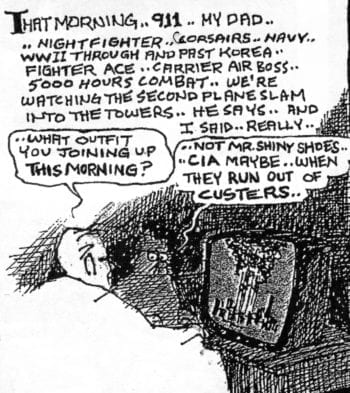

You don’t always know where you are going with O’Neill. He may take off with his father shooting down Washing Machine Charlie over Guadalcanal and set down thirty years later amidst the Bogside Massacre. But just when you are about to give in to head-shaking dismissiveness, here comes a letter from the tribal chairman of the Tai Akim Maidu, with a half-century experience in logging, signing on with the president of the Sixteen-in-One Gold Mine to the artist-author’s plan for “forest restoration, sustainable power production, and increasing blue collar jobs.”

You think Scott Pruitt had a better idea?2