The first half of this column explained the intentions behind it, but let's rehash things for a moment: as we all converge together to discuss, draw, or simply read comics, most of our knowledge is shared (Peanuts, a vague notion of Wimpy requesting things he cannot afford) whether we endorse or react against it---but our experience of zines is a personal one. Geography, a personal pantheon of aesthetics, varying levels of enthusiasm for continuing to amass piles of paper into one's life: all of this contribute to a unique archive of "containers of human creativity" (to use a phrase cartoonist Jason T. Miles once employed to describe zines).

I was intrigued by people's reactions to the first installment of this series. Some expressed excitement at seeing one of the first zines by artist Margot Ferrick. The work in question is from 2012, not ancient history in the least, but Ferrick's work has changed considerably since that moment. As I said before, zines disappear arbitrarily and without warning. A reader's favorite artist may have made something deeply heartfelt in the very recent past, but the work and the attitudes expressed may forever be obscured. With this in mind, for the final installment in this series, I've tried to write about a great many zines, in the hopes that works that have moved me might open up forgotten corners of what is possible in cartooning (which is the not so secret intention of this column in general).

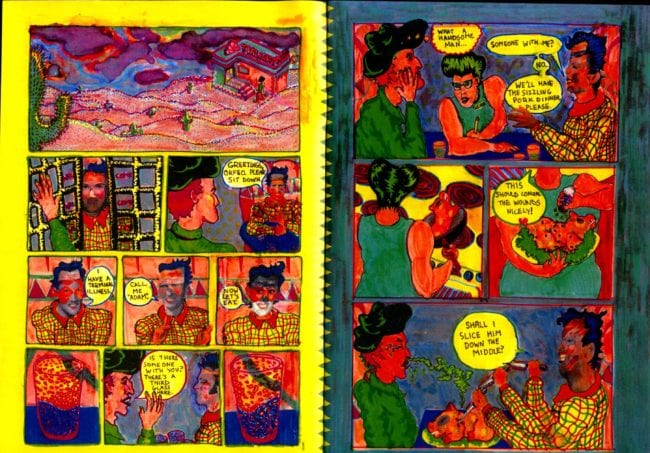

I'm always surprised that we so rarely see comics like this one, works where total expression is attempted without much concern for the trouble the reader will go through to grasp what's being communicated, but instead with a desire for the audience to catch up. Underground/art comics is a small world, with (it varies year to year) virtually no industry. Experimental works often allow themselves to fall into trends of the day, allowing their truly groundbreaking qualities to be go through a twisty straw constructed with of-the-moment popular aesthetic tropes to make the enterprise more palatable. Not so with this comic by Esme. A comic based on the life of Orfeo Angelucci, a man who claimed to be in contact with extraterrestrials, this is an uncompromising work: the characters change appearance from panel to panel, there is no visual relief in the form of negative space, facial expressions often clash with what is being expressed verbally and the subject matter itself makes one uneasy. I don't believe any work of art is made up solely of intentional choices and I don't believe in a 'gotcha' critique in which a nontraditional work is shown to be doing things exactly as it set out to do. And yet... with this comic, all of Esme's choices are thrilling, all add up to an experience that has no peers elsewhere, in a way I've never had (and I'm sure never will have) elsewhere. I believe Esme once expressed that she liked reading 'any comic' that was put in front of her, and this work, in spite of its seeming opposition to what cartooning is, can only be a comic. It presents us with an experience using images, text, and characters that is entirely its own, and rewards, both in feeling and intellect, the challenge it presents.

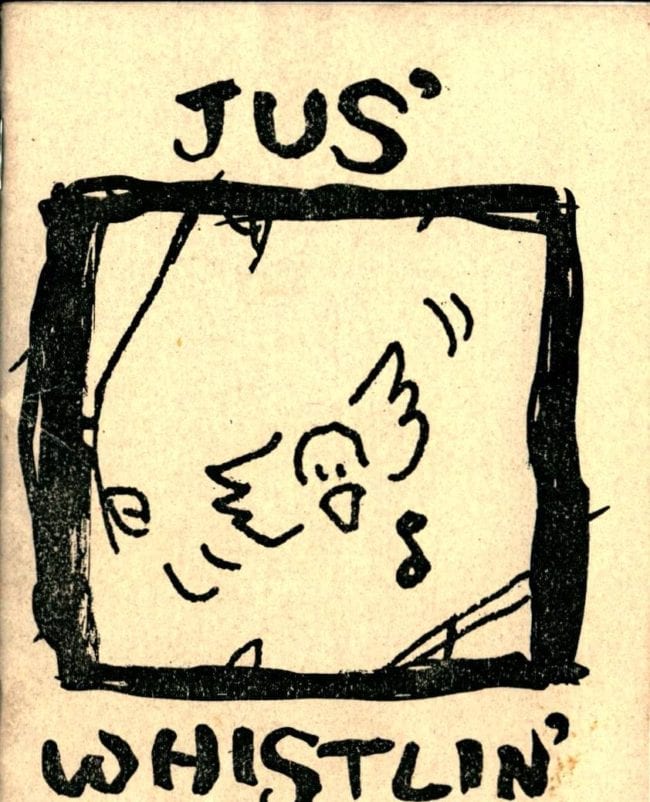

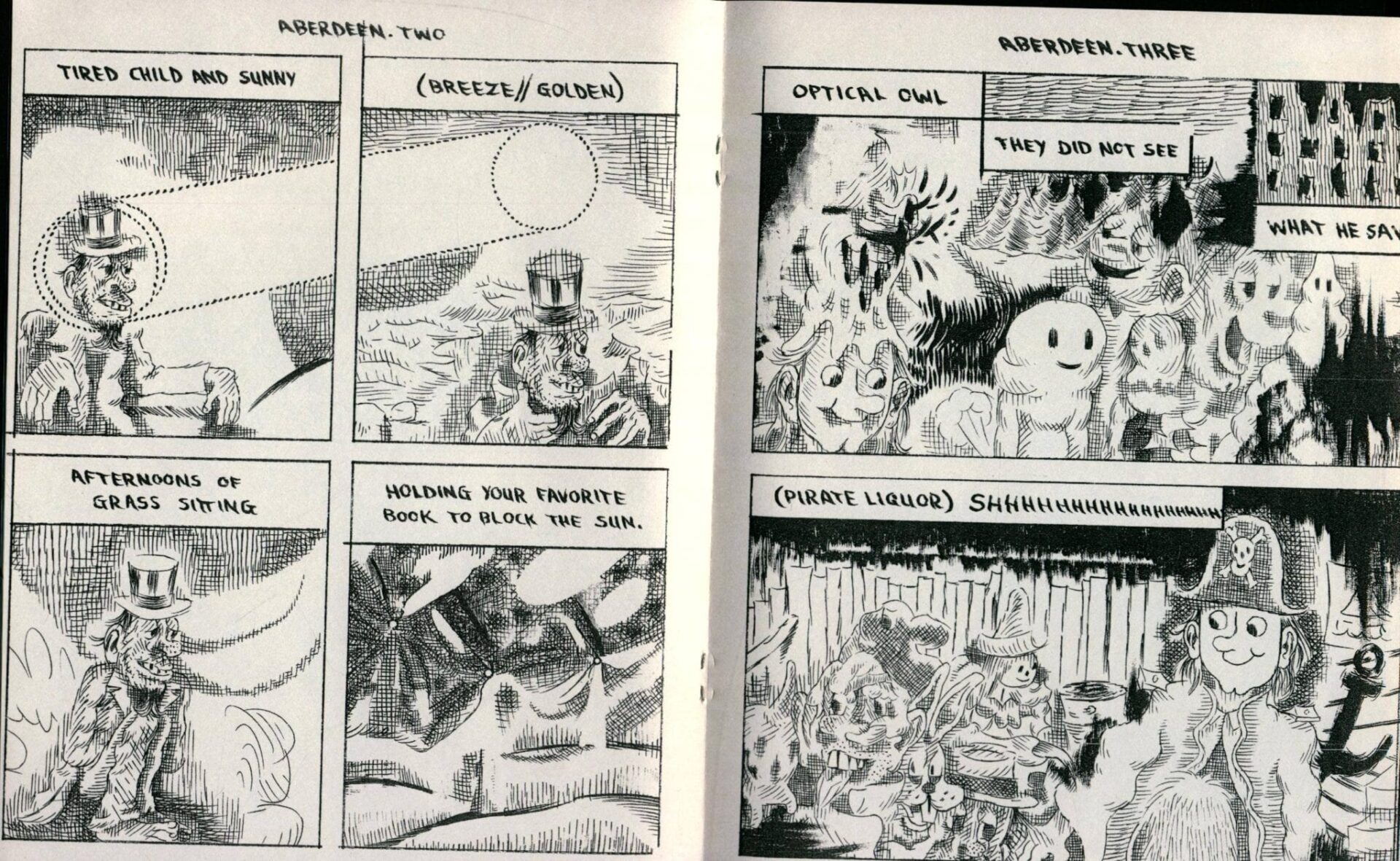

The cartoonist Jeff Levine recommended this comic to his peers in the early '00s and I think it left a big impression on everyone who encountered it. The style at play here became a familiar guideline for a lot of artists who came after (the unfortunately titled 'Lonely Boy' school of early '00s 'reaction against underground bawdiness' mini-comic making), but at first flush the work of Salazar and his peers felt (at least to me) revolutionary. A clear break from the 'literary' school of Seattle-centric cartoonists of the late '90s was happening here, but not in the way that was to come later. Like the previously discussed art of Greg Cook, zines like Jus' Whistlin' were not abstract or meant to offer clear and present obstruction to the reader---they were open and involving, even as organized narrative was discarded. But it was discarded happily, freely and without guilt. Salazar had a clear visual thrill that was paramount to his work, but in this zine it's not the over-arching focus yet. The bridge between the writerly concerns of 1996 and the painterly thrust of 2004 in underground cartooning circles has a bridge here in the brief moment of zines that pages of thinking and contemplation with a decidedly non-neurotic bent. I maintain that the rhythms of children's comics play a large part in laying the groundwork for all this, but it also must be acknowledged that comics like Jus' Whistlin' represent the beginnings of a generation that had fully digested the innovations that John Porcellino and Julie Doucet had spent the previous decade working towards.

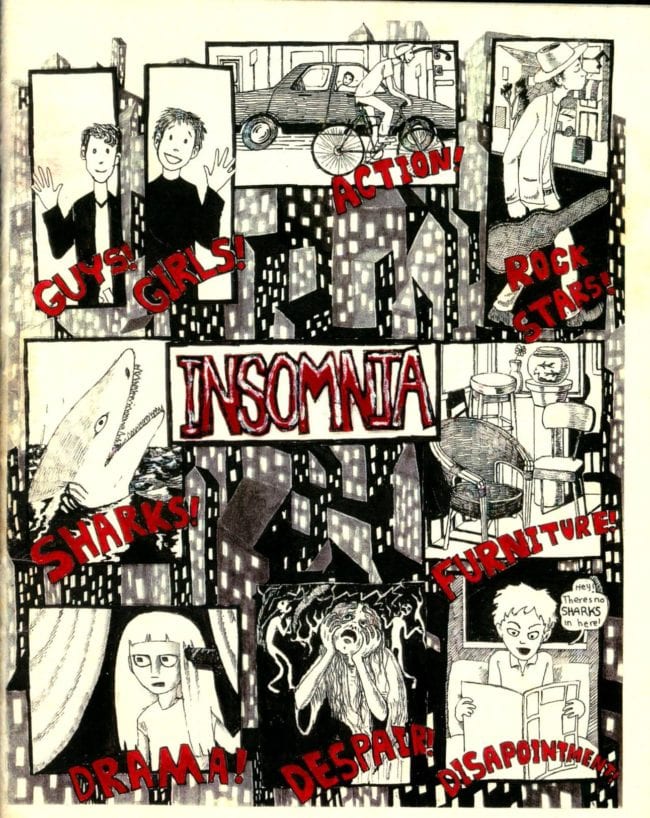

In 1998 I was still in middle school and I used to go to Al's Comics on Guerrero St. in San Francisco every Wednesday. One day, I saw a comic by an artist I'd never heard of, Gabrielle Bell. I knew what mini-comics were at this point and felt some vague duty to support them. The power of the work housed within these pages made that directive irrelevant. This comic did not need support so much as it needed a worthy reader. Bell's work is now beloved by most everyone capable of coherent thought in comics, and the cartooning of Book of Insomnia would (rightly) by considered formative for an artist who went on (and continues) to make work of the highest distinction and skill. But in 1998 Book of Insomnia was a zine out of nowhere for this reader, with no indication if there'd be more to come from the author, let alone hundreds of pages.

Yes, it would be hyperbole to say that Bell's work was fully formed in this early outing. Nevertheless, this comic immediately had a high degree of authority that is consistent with the authors future work. There is a clear impression of an artist using comics for all they can offer, telling stories without cutting any corners. Bell's comics today rarely crop a figure or zoom in for a close up, instead preferring to draw the whole figure, thus using the entire human body to maximize the potential for expressing full personality or the necessary drama of the moment. This technique is already (mostly) on display in this zine, as are the makings of a life devoted to figuring out how to tell short stories that would be a deep puzzle of frustration for anyone committed to find even the slightest fault with them.

I tend to think of this Zak Sally comic as 'the greatest mini-comic of all time.' Most of it was reprinted in the Fantagraphics collection Like a Dog but it shares with the above Gabrielle Bell comic the pleasure of having a (near showboating) surplus of zeal, information, and creativity held together in the modest form of a stapled zine. The central story, a biographical telling of Dostoyevsky's narrowly avoided public execution, might benefit from larger pages, clearer printing, etc. The work is so strong that it begs for better treatment than a photocopies. But a central beauty of zine culture emerges here: we have a work of art done with the utmost conviction from an author who believes in what is being done (there is no doubt of this), and follows through in spite of the limited means available. Nothing asks you to love this work besides the work itself. Why does Sally work so hard on figure drawing, why are the characters drawn with such personal investment in their emotions? After all, this is a zine, there is no financial reward at play here. Keep in mind, this is 1999---there is no industry to graduate into with that offers any stability. And yet here we have a seering work of art done for... respect for the peers of the past? Personal satisfaction? Art for art's sake? A gift to the reader? I think the answer is yes on all fronts and a hell of a lot more.

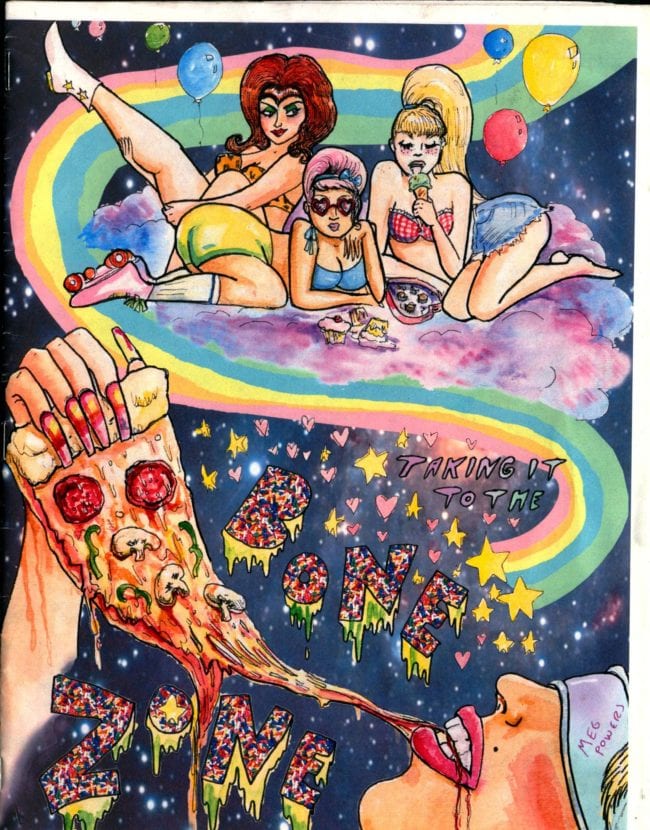

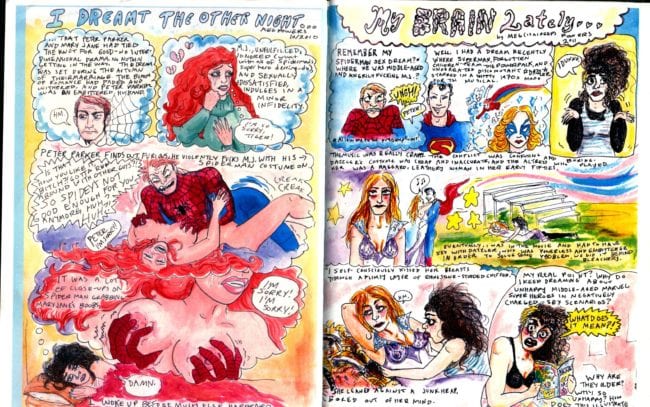

A zine by an artist I wish would make more comics. Powers work touches on a lot of different sub genres, unembarrassedly professing love for them all: superheroes, confessional auto bio, cosplay (although I believe Powers' is, in real life, a costume maker, so cosplay might be a reduction of her interest in these things), furry art, etc. Almost every corner of comics subculture is touched upon and re-filtered through how it intersects with the authors life. I feel like zines of today that are concerned with these areas are more explicitly speaking to ones own community and the politics of interest in a particular thing within that community. Powers, on the other hand, uses her interests for comedic purposes, but doesn't resort to selling them out.

This zine feels as if it was assembled at breakneck speed, with text scrawled in captions as if on the fly. Reading it, you're grateful that, however it happened, these pages were printed at all. The controlled chaos of what's expressed within seems to be rattling the very structure of the zine in your hands.

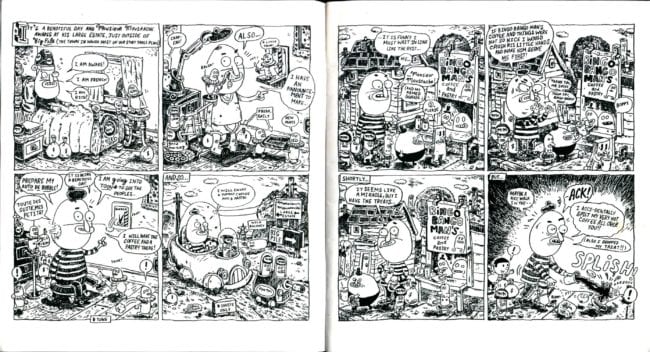

This issue of Jerry Smith's Rattletrap consists of Smith talking to his wife and kids and going about his day-to-day life. Unlike the nightmare of "indie" comics were the mundane is sussed out silently without intellectual focus, Smith leaves no room for silent contemplation. The items on a restaurant's menu are debated, excitement about an impending purchase of TeVo is broached. But the topics are covered in the way an auctioneer might describe them: this comic reads like a diary doing 120 mph.

Smith is a figure who doesn't attend the more artsy comic shows, instead focusing more on the zine world, but I always find his cartooning so satisfying that I'm surprised there aren't more people in art comics advocating for what he does. Smith, on the inside back cover of this comic, seems unconcerned with this, and has a different take on things, expressing a zine culture attitude shared by many but rarely stated so clearly: "In my head I've always done my comics for my family. I think of them as a legacy for my kids and their kids. I want my grandkids to be able to read my comics and to know me and the rest of my family. That's all that matters to me anymore."

I used to discuss this zine by Cook with my friend and fellow cartoonist Jesse McManus. I don't remember hearing anyone else ever mention it, much less write about it, but I recall us both being greatly influenced by the idea of a zine that is a single thought, drawn out over a half dozen pages, and then sent out into the world. China Guy is exactly that: a narrator addresses someone as a car drives around a landscape. It's subtle but there's such a break with the accepted notion of what a zine or mini comic must consist of. Instead of filling his work with exaggerated personality and packing panels with information (as seems to be an unavoidable default style, era to era), Cook concentrates on one emotion, one line of thought. The artists of the late '90s who were often associated with Cook (James Kochalka, Ron Regé, and Megan Kelso) went in this direction often, but rarely with such unembarrassed love. This is the balanced public face of comics that consist of set of sentences written alongside images that don't ask for each other but cannot be parted once joined.

This is a relatively recent zine in comparison to others under discussion, but is nevertheless an important work in relation to the rest. Marinac has a particularly Canadian commitment to zine-making, at times seemingly creating a zine a month. Covers are made with collage, figures worked and reworked, found text added to abstract renderings of gesticulating human forms. Somehow, these drawings work closer function more as comedy than abstract expressionism, but I think the binding aspect here is simply creativity. Marinac's output is prolific, but far removed from a 'punch the clock'/'grind 'em out' stance. Instead, each arrangement of the human body and text is a new opportunity for a never before rendered shape and/or (most often 'and') an unexpected language statement. Marinac's template repeats but what boils up over said template is always new. I try to get every Marinac zine I can find, as they all add up to a particular swath of creation.

Sketchbook Party by Allison Cole, 2002

I loved the cartooning of Allison Cole for it's compact sparseness and for it's blueprint-for-Dell-Comics-cartooning vibe. A lot of underground zines at the time this was made had a high level of either aggression or shaky lines. Cole's work felt more like stickers expertly arranged on the page. Simple emotions (walking down the street, for instance) are quietly amplified by excluding all other information. Where other cartoonists would search for a resolution to a feeling or a visual idea that felt unearned, Cole would draw only the initial seed of a narrative and leave it at that. I liked Cole's cartooning in the same way I liked EE Hibbard's Golden Age superhero comics: simple figures arranged clearly, drained of emotion except the most essential.

Dylan Williams, the publisher of Sparkplug Comics, saw the Ego series of minis by Dunja Jankovic at a festival one year and immediately told everyone he knew about how great they were. I think if people are aware of Jankovic's work, they know the Department of Art Series, or her more recent highly experimental digital offerings. Looking back to her work from ten years ago is a revelation, as issues of Ego have such an almost conventional comic-book surface, with all the transgressions against the form simmering within its structure. Jankovic said somewhere that she moved to New York in part because 'it's the cradle of comics,' where comic books were born. A key to understanding Jankovic's challenging work might be this true-blue love of the form, which contains a faith that the medium can withstand the obstruction Jankovic subjects it to. The Ego mini comics are in dire need of a collection, as each one of them is a temple of comics-as-art teaching. To me, they are the Krazy Kat book collections of my mini-comics library: works so full of ideas and innovations that I'll never part with them.

Blaise Larmee edited this zine of interviews, and on the inside front cover we read the following statement: 'Comics Youth does not present comics as culture, but rather investigates the culture(s) within comics. In this sense it provides an interior view of the contemporary comics landscape.' So in part what we have here is another entry in Larmee's labyrinthine commentary on how artists present themselves. To a simplistic eye, this zine might not have much to distinguish it (besides an assured design presentation) from how most of these things operate within zine and fan culture: three contemporaries of the editor talking about their work with the endorsement from the editor so obviously assumed that it doesn't need to be stated. With Larmee, there's a lot more at play here. Many questions come from a genuine place of interest while others pick apart the authors work from an 'enemy from within' standpoint. The very idea of this zine being printed rather than posted online offers a pose worthy of critique in and of itself, as the editor toys with the notion that a scrappy print zine is in some way more 'authentic' than a digital offering might be. Larmee's work confounds readers because it never shows its hand: is it parodying every impulse that it catalogs, or is it a record of total involvement in cartooning culture? Or both/neither? I tend to think there is a strong humor element to everything Larmee does, and this zine (which fits into a decade plus project of commenting on the world of cartooning) is no exception and is an essential component of the puzzle that the editor has been constructing.

Bessijelle made this zine on a home printer, and stapled it at the edges---everything about the assemblage of this comic is worked out by the author on a system of their own. A heartfelt pride in its making comes through, which is augmented immeasurably by the purposefully labored over work within. The author made the art according to their own principles and found the images to be powerful, thus making reproduction and dissemination of the work essential. But how to go about that? Like some of the most uniquely beautiful zines, the printing is as personal as the drawing within, and if the reader brings themselves to it, a total work of art can be seen. Unlike self conscious art zines that stress their expensive production values, this work's quiet features make it priceless.

This is a short comic about domestic abuse that does not make its themes obscure. Still, things aren't spelled out in exhaustive detail. Instead, the issue at hand becomes an emotion that hovers over everything. What we are left with is a force that attacks the central characters (a mother and a daughter) not just in the action depicted, but in every line drawn, every composition--nothing is free from the oppressive situation that we, the reader, are drawn into. This was a very important comic to me when I first read it, and suggested the poetic potential of comics in a very powerful way. I've said it before, but this comic is poetic not because it mirrors poetic forms but because every aspect of it contains feeling and no note of it is compromised for explanation over expression.

Dylan talked a lot about the power of vagueness. I didn't understand his take on the term until later, but I'm going to try to explain at as I grasp it now: clarity feels like reality but is actually an abstraction of it. Vague is how things actually are, and art with the will to move you must be vague. Robert Bresson's movies feel stilted but are more like life than mainstreams films synthesis. Hollywood is the abstraction, not the other way around.

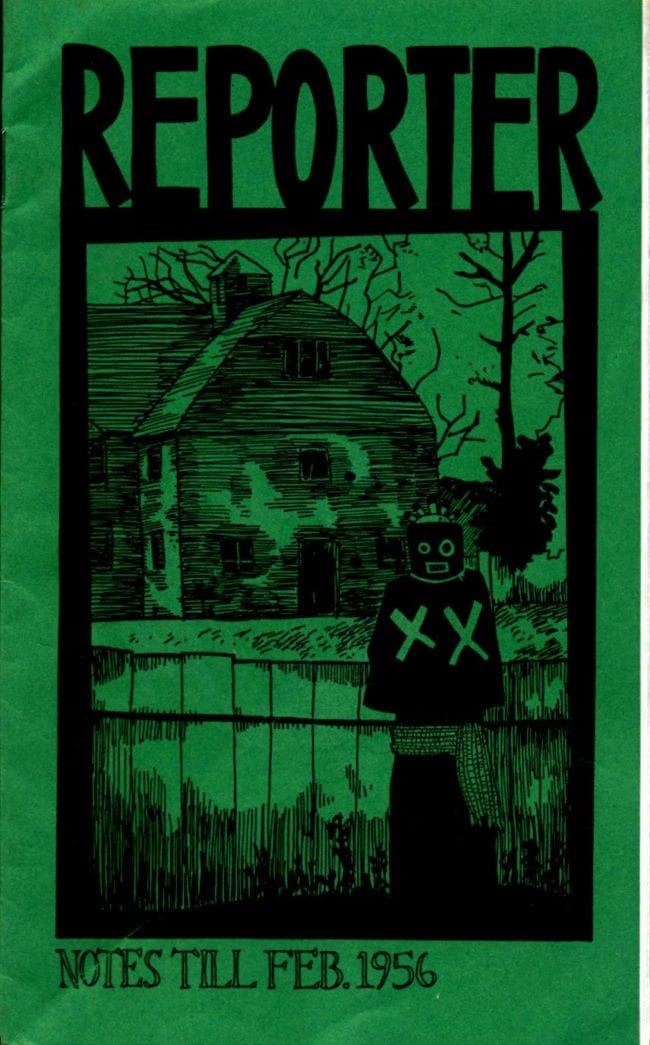

This zine is then a very interesting piece of the vast life project of Williams, which was devoted to realizing the limitless potential he found in making comics and working with the comics of others that he cared about. Reporter was Williams's flagship comic, and after reading the first issue, I assumed the comic centered around Ivar, a young Tintin-esque character whose 'occupation' was to record everything that happened around him in notebooks. I felt that he was the 'reporter' that gave the series it's name, but each new issue complicated the succinctness of this hook. The world of Reporter was vague, but not for lack of meaning. There was intent behind every decision---in fact there was so much that a straightforward by-the-numbers storytelling path couldn't contain the depths of Williams expression. And yet, as anyone familiar with his poetics and scholarship knew, Dylan wasn't a enemy of crisp storytelling. In fact, he was quite partial to it, as his writing on Alex Toth and many of his publishing choices indicate. There was a conflict at play here, and this zine is a funny commentary on all that. This edition of 'notes' to better explain the Reporter universe does help a little, but also brings up dead ends and false leads. Clarity and vagueness unite within these pages, a small window into a corner of what Williams was up to.

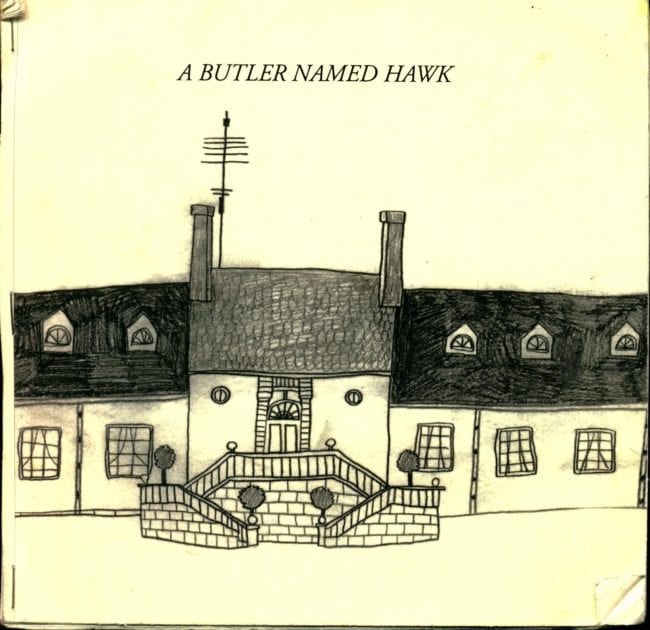

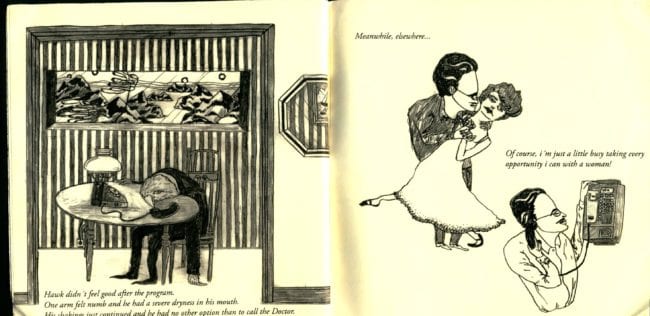

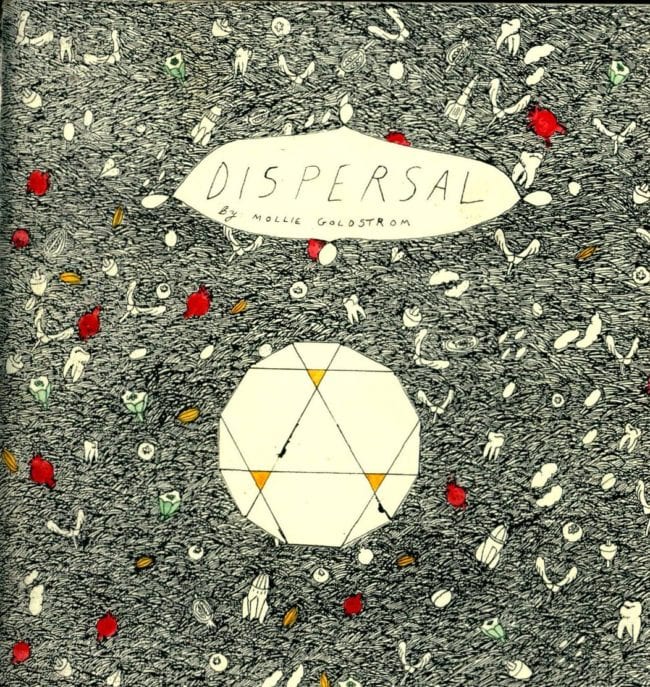

Goldstrom's work occupies a place of under explored opportunity in cartooning in that it carries on the legacy of Edward Gorey's embrace of absurdism, humor, specific dress and theatrical poses, all the while retaining an independence of expression foreign to the work of the master. Goldstrom's minis always contain detailed worlds, but unlike many of her contemporaries in age, she is not invested in sci-fi or video game terrains. Instead, an impossible scenario explained with a straight face and exacting skill is what is achieved here. I wish this zine was more widely seen, but its obscurity makes the overpowering beauty of its cover all the more impressive when I bring it out to show to people.

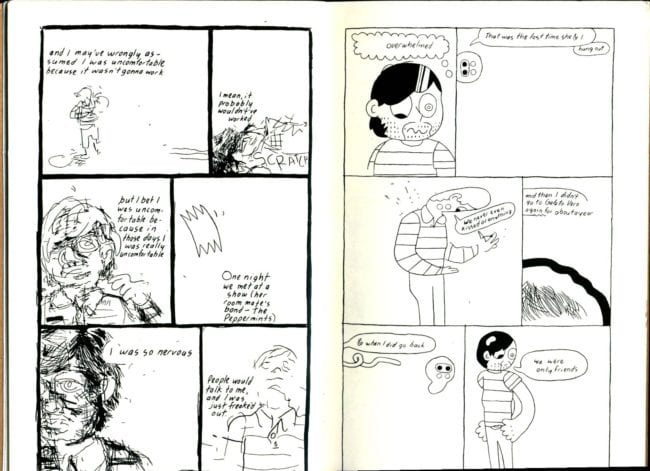

A basically perfect comic. Overby is a cartoonist who has digested what Panter, Fort Thunder, Rege and the history of art comics means (to him), and rather than devote himself to pastiche, has weaponized his scholarship into something new. That's how it feels to me at least, an artist saying, 'I'm aware of what came before, but why didn't anyone try THIS?' The 'this' of Jessica centers on a memory of relationship from the past, and alternates from scraggly lines to tightly inked cartoony bodies. Reading this comic feels like the sonic equivalent of static turning into a burst of pure pop and then heading elsewhere, not out of impatience but from exuberance.

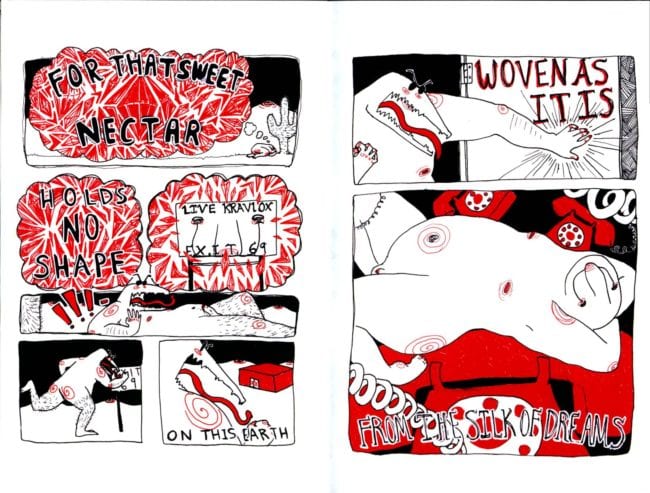

I'd never heard of Isabel Reidy until I saw them do an incredible reading of this comic in 2016 at the CAKE festival in Chicago. I don't think I've ever seen a comic reading that equalled that one exactly, and reading the comic itself is on par. Reidy's language is far more flowery than most cartoonists allow themselves to attempt. But let's make no mistake, it's assuredly flowery, rather then groping for meaning by adding pretty words. Reidy is another example of true comics poetry: words are selected with the utmost precision and no moment for expression is wasted on explanation (although the comic reads quite clearly). Kravlox is the subject of a monologue on desire, but the drawing of Kravlox calls such desire into question: Kravlox looks ridiculous. The rules of the comic point us towards a different reality, one in which the absurdism of Kravlox does not repel attraction, but rather makes it the only sensible response.

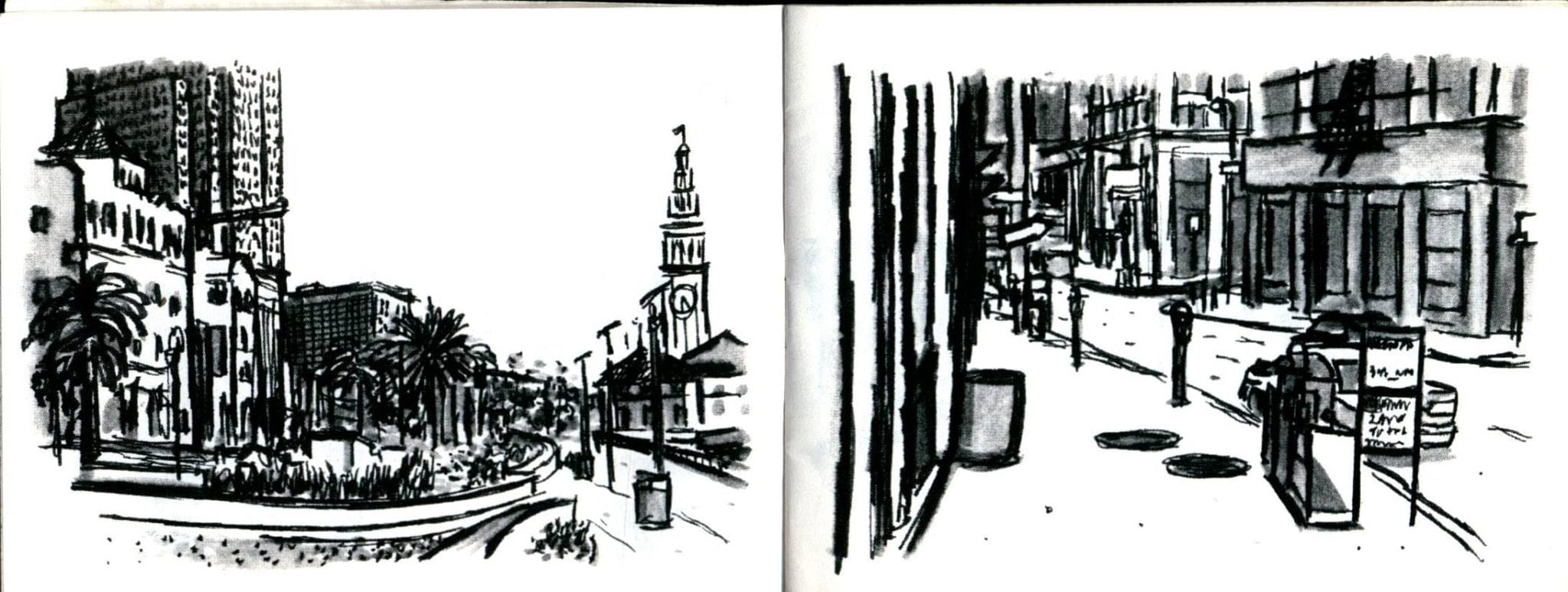

Another zine recommended to me by Jeff Levine. Santoro is well known now for his cartooning and for his writing about comics. But in 2000, this zine felt mysterious and quiet. Drawings of buildings, alleyways and foliage interspersed with minimal text and notes: a record of what the artist noticed and thought, presented together. Observations and contemplation's made into comics by existing side by side. I thought this zine was beautiful when I saw it because it didn't steer you in any direction, it was humble in that way. It didn't court involvement. There was an austere 'tack it or leave it' attitude at play here. A statement made concisely and obliquely.

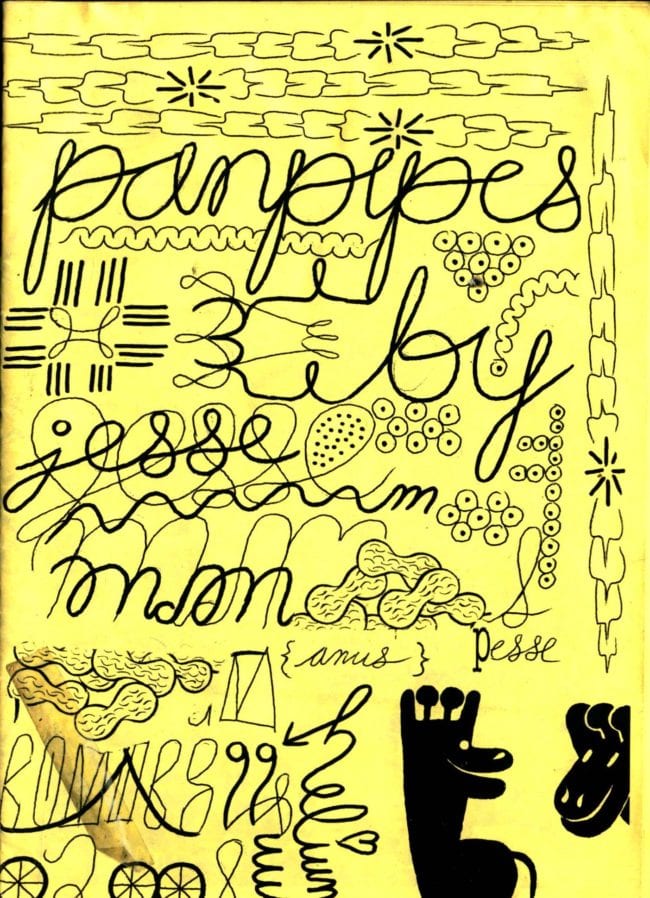

This is one of my personal favorite mini-comics of all time for a variety of reasons, but the story I'll tell about it here relates to a specific aspect of my own process. McManus was one of many cartoonists roommates I had while living at 282 Broadway in Brooklyn, off and on from 2007 through 2013. The apartment was later nicknamed 'Cartoon House' as it became the home of countless artists and writers working in ad around comics. Besides myself and McManus there were, at various times: Lizz Hickey, Victor Cayro, Jon Vermilyea, Keith Jones, Bill Kartalopoulos, Chris Ortiz, Carly James, Clara Bessijelle, Becca Kacanda, and more. McManus's room was next to mine and we were around the same age. At the time, Jesse's working practice consisted of waking up in the middle of the day and working on comics throughout the evening and then into the night and early morning. I feel like I had been approaching a system similar to that, but never fully committed to it. Jesse's enthusiasm for cartooning and his discipline was highly influential to me, after seeing it in action. Since then, most of the day feels like a gauntlet of tasks and obligations that must be cleared away until a free swath of hours is lined up at the very end, and all attention can be focused on cartooning. To be sure, this is a worldview with some unhealthy qualities, but it is one that has yielded a lot of happiness---McManus's example of this kind of worth ethic would never have been so alluring if the work in this comic hadn't looked so beautiful to me.

Jones was a roommate from a different era of Cartoon House than McManus and as far as I can remember, he worked on this comic while living there. If it wasn't this one, it was his book Secret Times---both works were a break from the style Jones had previously worked in. With his work from this era, an unmistakably 'comic book' style emerged. I remember Jones working on these pages on the kitchen table downstairs and watching his cartoon universe turn into one deeply informed by the history of golden age cartooning. Jones and I would often go to Roger's Time Machine in Manhattan together, a store full of long boxes containing Golden and Silver Age books. Watching Jones freely take inspiration from this work and filter it into his world of cartooning that superficially would appear to not be able to accommodate rhythms from the past was important to see. Often times a love for the past becomes a retread in works made in the present. But with Jones they are used as an ingredient of energy rather then a disjointed meal of different eras. Jones's recent book Secret Times feels like a Gold Key comic but without the conceit of it being a tribute or a facsimile. Instead the colors, shapes, and beats are understood and turned over to Jones for his own purposes.

I don't think I've ever gotten over this comic. I bought it from Bell at a festival when I was still in high school, and I feel like the care that was put into it, the craft that went into every drawing and the time spent labored over all the dialogue to insure that Big Pile functions as a living breathing object of 'ultimate cartooning' made (almost) flesh pushed me onto a track of believing in the highest potential of what comics could achieve. It might have been an early moment of cartooning faith where the future fails in comparison, the shock of the new and all that. But I also feel like there was something in the air in the late '90s and (very) early '00s. Before the (faux) 'explosion' of the graphic novel market, there was no future for artistic comics other then making the one you were currently working on extremely excellent. The graphic novel market provided no real future either, but did dull the sharpness of art for arts sake. There were paths to go down now, and you better get your work out there! Prior to all this, in 2001, what more was there then the dignity of making a perfect comic? This, to my young mind, seemed like what was on people's minds and Big Pile Comics functioned as the manifestation of that perceived attitude.

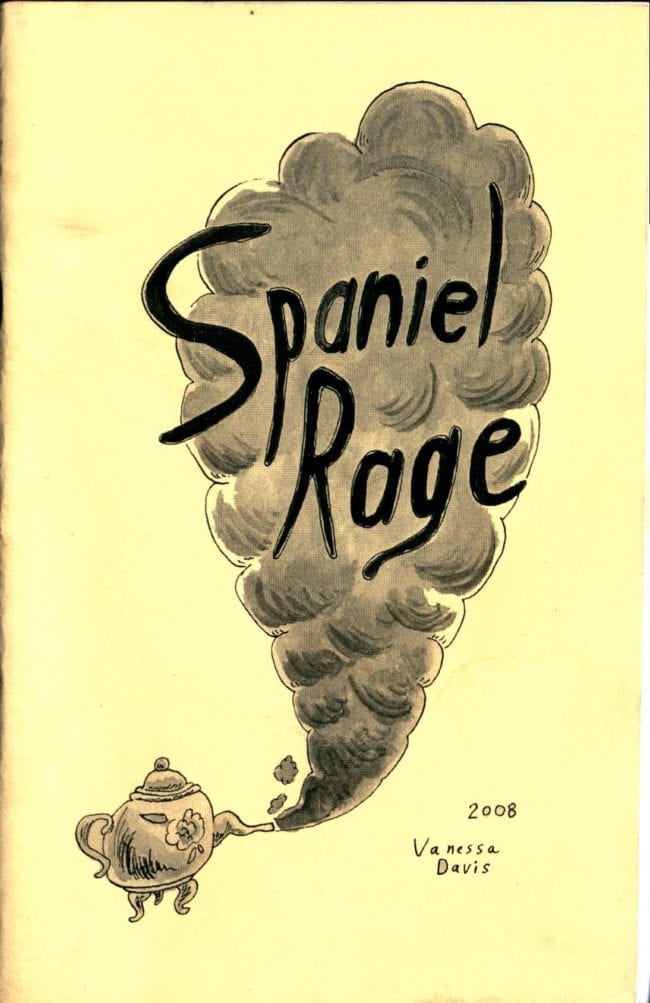

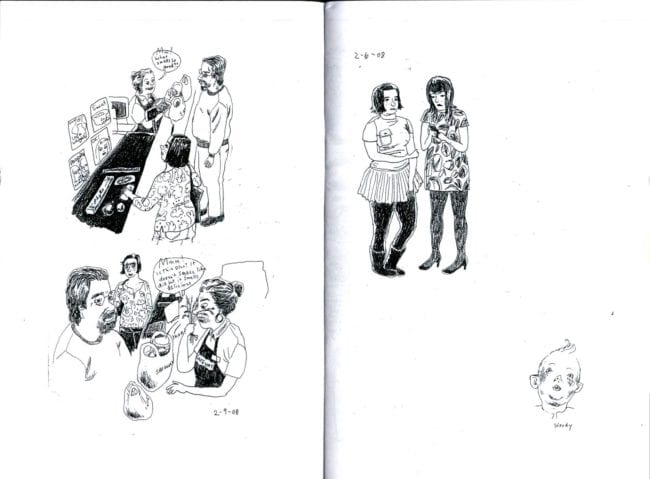

My first exposure to Davis's work was the mini before this one, issue #2. When picking out items for this column, #2 seemed like the clear comic to select, as it made a big impression on me at the time. But this later zine, after Davis' work had been celebrated by most everyone in 'our' corner of comics, is probably my favorite single piece of art by her. The drawing has, at the moment captured here, tightened up into a comfortably scratchy style, aiding in the depiction of clothes, postures and scenes that make up the daily-life world that Davis chronicles. Even when the pages here are sparse with drawing, they are packed with reportage, every inch of the page that has ink contains information. Davis's cartooning happens within her figures: a story is told in all the choices that go into what happens with a specific human body rendered upon the page.

A related branch to our fascination with Greg Cook's China Guy, Jesse McManus and I paid close attention to everything Jason T. Miles did, especially after reading his excellent comic Dead Ringer, a major touchstone for us both. I think a concentrated interest in JTM is true for a lot of comics readers and artists, but not something that gets mentioned enough in print (or "posted type" as is the reality of now). Here's a convoluted attempt at explaining the appeal Miles has for me: I saw an interesting show of Matisse's work at the Met once, a process show called In Search of True Painting. Canvases where ideas had started were hung next to later works where the notion had been refined. But unlike most other artists, Matisse's heart was as present in the inchoate attempts as it was in the 'mature' masterpieces. The show suggested that no opportunity of expression was wasted for Matisse: a finished work would always contain a non-throwaway sentiment or creative shape. Miles is like this for me. Any zine, illustration, short story, or longform work is a moment to try something worthy of one's heart and mind. Pines was, for a time, the flagship publication of this singular artist.

A favorite cartoonist of Dylan Williams, this is one of the most assured mini-comics I've ever read. As in Sally's Recidivist, the amount of work and care that went into this story and then presented as a defenseless zine out in the wild is a moment of poetry in its own right. The story---about starting over and the luck of being able to do---could easily be pap, but Barrett makes it anything but. There's a relentless conviction here to make each panel part of the emotional web at play. I think Barrett knew how good this story was and didn't allow for a moment of weakness. More Phillip Barrett comics, please!

Another relatively new zine that has risen to classic-status for me very quickly. The title says it all, sort of: one hundred drawings. But really it's one hundred drawings of faces talking back and forth to each other in the service of wordy 'gags.' And yet... they aren't exactly that either. Somehow, these pages become gag like the more you read through the zine and work better the faster you breeze through it. The characters insult each other loudly but the insults are benign and flirt with being positive statements when read aloud. Is everyone confused? No, they've just tapped into a new kind of comedy---I wouldn't call Chen's gag writing 'awkward' or 'deadpan.' That throws you in the wrong direction. How about "absurdist John Stanley/Don Rickles brainstorming session?"

Annie Murphy's I Never Promised You A Rose Garden is an extremely important project. Murphy is a hard-to-do-her-artistry-justice cartoonist who isn't extremely prolific, so each new work is worth studying. More then that though, Rose Garden is a historical work that is more vital then that description usually suggests in zine culture. Instead of a 'historical' zine that is concerned with the changing storefronts of main street, Murphy's subject is no less than the history of mood, the underground itself, sordid half-truths, and tragedies involving all of the above within her home of Portland, Oregon. Murphy is a cartoonist like no other, more emotionally precise than most artists who work in comics. Murphy's feelings are clear to her but unique in spirit: she communicates them to the reader without noise and we are left with new heartbeats.

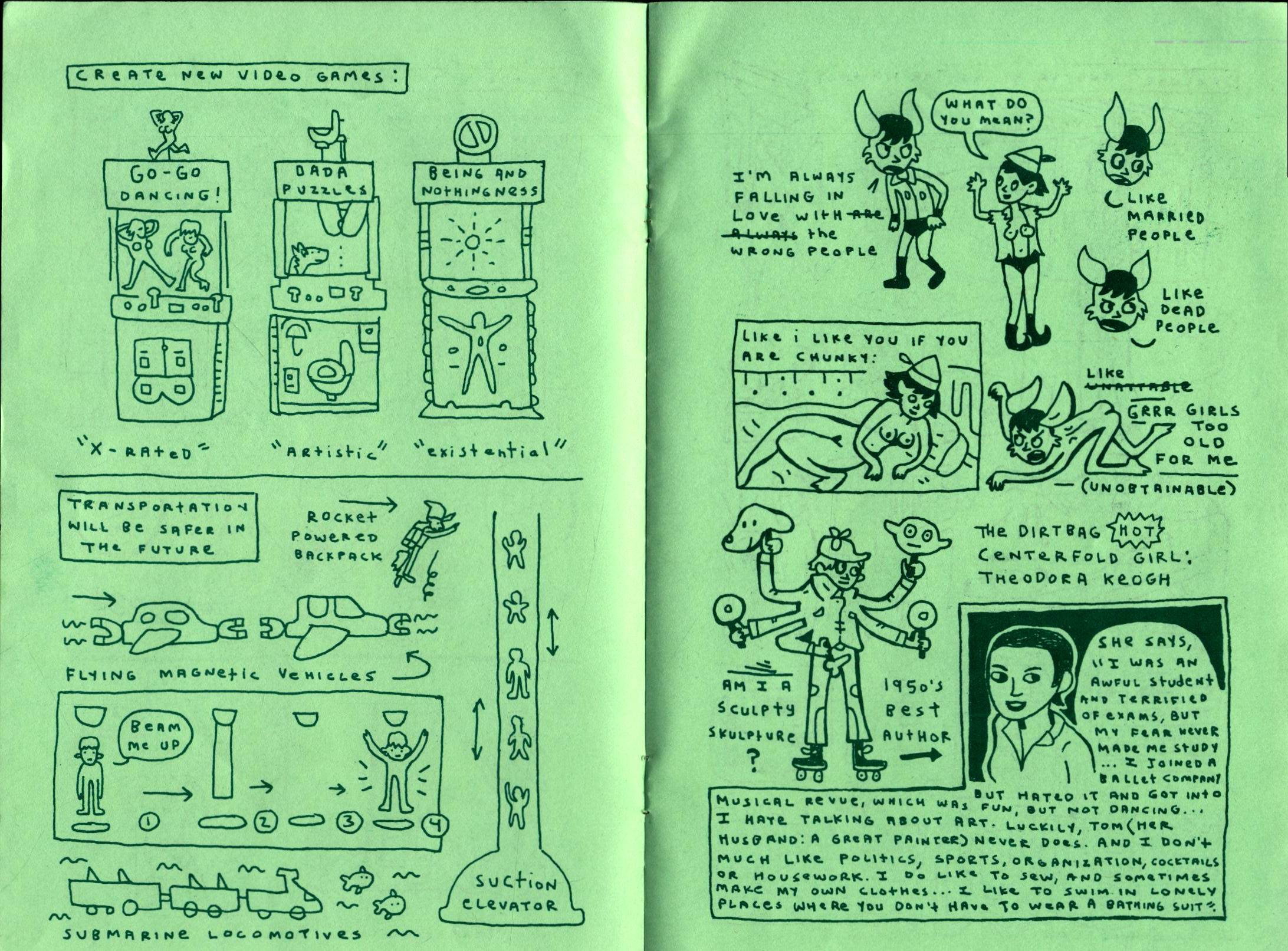

Dave Kiersh (of Dave K. Teenage as I remember him being referred to when this zine came out) has made a lot of comics. The Dirtbag series remains my favorite, probably because it was the most ambitious thing Kiersh attempted. All of Kiersh's work centers on teen loneliness and lust, suburban kids with Jimmy Stewart meets Russ Meyer minds. But Dirtbag was from a time where Kiersh quietly built a complicated world around these tropes: new technology, costume ideas, notes for plays, biographies of authors: all of this presented on carefully designed pages, composed by Kiersh. A thoughtful collection of this work might be a blueprint for a world that, if it was made real, would be even more unimaginable to today than the highly alien spectacle it envisioned in 2002.

Another resident of Cartoon House, Victor Cayro is a near-mythic figure in comics, immortalized early in his career by Eddie Campbell for his antics at a mid '00s SPX festival. Cayro's persona is bound to his work, but it should never obscure what an incredible cartoonist and drawer he is. There is a visual gestalt to everything he does, that's obvious. Less clear is the intricate mind and parody-within-parody-within-parody/visual-pun-within-societal-critique that Cayro's writing expresses. His art amazes like a more detailed S. Clay Wilson, but I think it's the literary Cayro that surpasses such comparisons. He doesn't release enough zines, more typically popping up as the best entry in any given anthology he appears in. That makes this publication, a collection of gags and drawings, all the more special.

I wanted to write about Levine's Snapshot zine, which was a very important mini-comic to me when I was starting out in comics. The only Levine work I could find while preparing to write this column was his wordless Untitled series. While I prefer Snapshot, this column cannot go without mentioning Levine, a guiding influence on many of the people written about here and an artist whose work strikes a deep contrast to trends of today. Levine's work doesn't throttle the reader or go out of it's way to please or confound. It is what it is, a persons experience in the world rendered well. Snapshot was full of writing and observations, almost diary-like, alongside Levine's washy landscapes. Untitled excludes the writing, but we still have Levine's unmistakeable eye on the world, with each new print release adding to the chronicle of his time walking and thinking. A thoughtful artist who I always found satisfaction in spending time reading.

I think Lilli Carré is the best cartoonist of her generation. I probably read this zine a couple dozen times the year it came out. So often, a young cartoonist comes around with a confident style, an ability to tell stories and a desire to work. These three qualities are a rare combination and readers often celebrate finding them in one author. The cartoonists I care about are the ones that have some kind of combination of those elements but retain the elusive all important fourth trait: a mind with moving things to express. Carré's individual drawings are perfect beats of story, and they are a (rich and complicated) pleasure to even glance at. There is 'cartoon integrity' (everything retains the weight and tone from the assured first panel to the last) and the characters do not over or under perform their emotional tasks. All the textbook requirements of what 'true' cartooning is, Carré controls. But it's into what terrain she uses such control to direct us that is worthy of our attention. In this story, a character views a double of herself out and about. We read the implications of this well-worn setup in the facial acting of Carré's characters, and it's here where a unique intellectual and psychological manifesto is typed out. Carré's cartooning is airtight but her drawn melodrama connects in a way that can't be emulated and must instead be experienced.

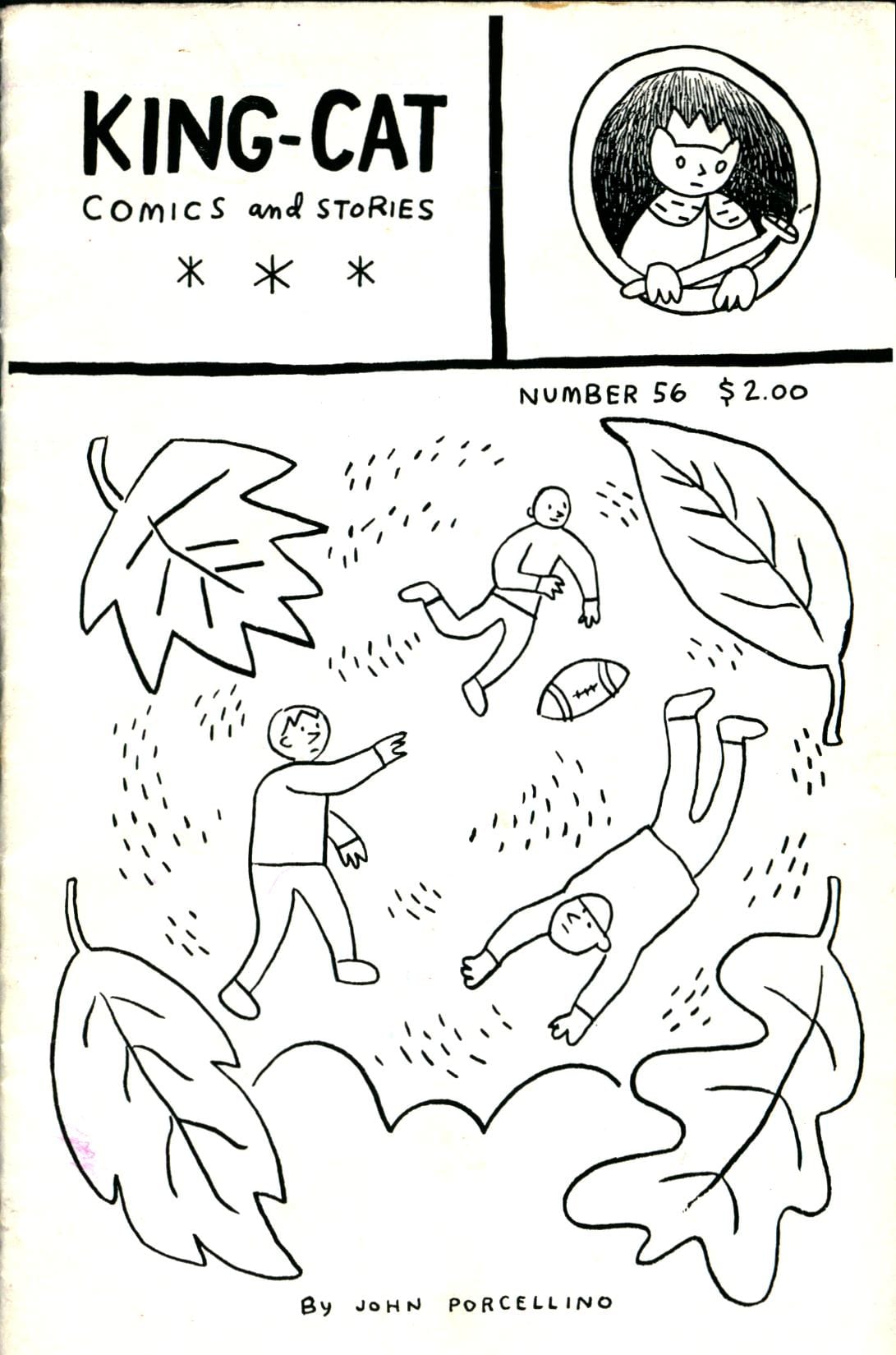

No writing about a history of one's mini comic reading should go without a deep bow of a mention to John Porcellino, a person who has devoted so much of their life to making and caring for zines. I'll end this long column by stating a few simple facts: #57 was the first King-Cat comic I ever bought and I'll never forget reading it. It remains one of the most aesthetically pure and challenging things I've encountered, and informs my appreciation for so much of the work written about here. I'd still like to draw something as perfect as the three young men on this cover.