With a career spanning five decades, Sean Phillips is among the most prolific artists of the so-called British Invasion. Despite this, he is also among the most under discussed. Phillips’ career has included stints on iconic UK titles such as Crisis and 2000 AD, Vertigo titles like Hellblazer and Kid Eternity, and the hit Marvel Zombies and its sequel. He is perhaps best known for his long-running collaboration with writer Ed Brubaker on crime titles such as Criminal, Fatale, and, most recently, Reckless. Outside of comics, Phillips has applied his illustrative talents to album covers and artwork for the Criterion Collection releases of 12 Angry Men and Blast of Silence. Phillips is described by collaborators as something of an idyllic partner, approaching each job as knowledgeable and versatile journeyman. The breadth and depth of his genre-spanning portfolio is a testament to this. Ian Thomas interviewed Phillips by email in late 2021.

Ian Thomas: Comics were on your radar from a very early age, but can you talk about your earliest memories of comics? Were the American imports that were available at the time, Mighty World of Marvel and Spider-Man Comics Weekly, readily available in your area? When more imports became available were those available in a way that was convenient? Were you equally interested in Dan Dare and the war comics that were produced domestically?

Sean Phillips: I can’t remember a time when I didn’t read comics. Mighty World of Marvel started when I was six or seven, reprinting the earliest Fantastic Four and Spider-Man stories every week. I’d already started reading comics before then, UK produced humor comics and imported DC comics. War and sport comics never interested me and Dan Dare wasn’t still being published then in the early 1970s. Imported US Marvel comics were very rare in the small town I grew up in. I don’t think I saw any until I’d been reading the UK reprints for a couple of years. Discovering American Marvel comics in my local newsagents shop was a revelation. British reprints were in black and white and suddenly this whole multicolored world exploded in between those glossy covers. I was hooked! For a few years I read the UK reprints of 1960s Marvel along with the new 1970s imports. My friends and I would read and swap each other’s comics, so we probably read every Marvel story from 1961 to 1978, along with a lot of DC and UK comics. After 1978 when I was 13 and my parents divorced, money was tighter so I didn’t read as many comics for a few years.

In your earliest works, such as the “Kids from Rec Road” strip you did with Pete Doree and David Holman, were you focused on emulating the format of comic strips more than you were of emulating the work of specific artists? When did you begin to make the connection between the work you enjoyed and specific artists? What artists stood out to you?

We started making the “Kids From Rec Road” strips in 1977 when we were 12, starring ourselves in film and comic parodies. We did spoofs on Star Wars and Conan and Kiss, shoe-horning in plenty of other comic characters from Shang-Chi to Snoopy. Emulating other artists never came into it. We made them purely for fun, never really thinking it was possible to have a job making comics. The immediacy of comics is what drove us. A comic we’d read the day before or a film we’d just watched on TV could be used in a comic strip straight away. I don’t think anyone apart from ourselves ever read them.

Back then I didn’t care who drew the comics, I liked them all. Jack Kirby and John Buscema were my favorites, but I read whatever I could get. Very few US imports got to my home town, so I bought whatever was available.

You met comic artist Ken Houghton in 1978 when he held a lecture and demonstration for students. How old would you have been at this point? Having already produced some work, what were some of the technical aspects of the craft that were revealed to you by that instruction? How about from a professional standpoint?

David and I had had a weekly comic strip published in our local newspaper when I was 12 in 1977, drawn in whatever pens my dad brought home from his office job. We had no idea how comics were actually made.

Pete and I (and my school art teacher Russ Nicholson) started attending Ken’s evening classes in comic art when I was 13. Ken taught us everything from art materials to figure drawing to composition and storytelling. Before his classes I drew with markers and ballpoint pens on whatever paper was to hand. He introduced us to Bristol board and brushes and Indian ink. For Christmas 1978 I got given a copy of How To Draw Comics The Marvel Way and that reinforced what Ken was teaching us. Ken approached drawing comics from a European viewpoint though, where one artist does it all, pencils, inks, and colors if needed, rather than the US method of separate artists for each stage.

That meeting opened a window into your earliest submissions. What did that early feedback from editors do for you?

My earliest work, when I was 15, was ghost-pencilling for Ken, which he would ink in his style. I’ve no idea if his editors knew that was happening, I never had anything to do with them. The first few years my only contact was Ken, and then by the time I was 18, and I was doing all the art myself, everything was done through my agent. Mike Fowler was Ken’s agent and then he took me on as a client when he thought I was ready.

When you started getting work doing girls’ comics—as they were called—what changes did you make to the crafting of your work in terms of tools and technique? What constituted reference materials at this time? Had you started to consciously accrue useful reference materials?

Pages were drawn on Bristol board in pencil and then refined in ink using a sable brush and occasional nib pens. The only reference would have been other girls’ comics, and the local library when I needed to draw something specific. By the time I was around twenty, I’d also built up a collection of magazines aimed at teenage girls, which were very useful for the fashions if I was drawing a contemporary strip. Being only a few years older than some of the characters I had to draw probably helped too!

Artists and writers didn’t interact directly on the work you were doing. Was there much conversation with editors about nailing details and tones or were you focused solely on turning the work around?

Everything was done through my agent, I had no contact with editors or publishers. I tried my best to do work that fit the particular publication, but sometimes I just wasn’t the right person for a job. A war story I was woefully unsuited for springs to mind!

Did you feel free to experiment on the job or did you wait until you were satisfied with a technique before applying it to paid work?

This was all quite basic stuff, just black ink on paper, so experimentation didn’t really come into it. I was just trying to draw as well as I could at the time.

Working in this anonymous way, did you consider the work you were doing to be in the same medium as the Marvel work you were drawn to at a younger age? Were you consciously trying to make your work distinctive by this point?

When I started out ghosting for Ken, the aim was to draw as much like him as I could, and his influence is still there today I think, especially in drawing girls. My style came from my inability to stay close to his style! Trying to draw comics while still at school, and a terrible page rate, made me draw as economically as I could to get the work done. It was better than having a newspaper round but I never thought it would be more than a paid hobby. Marvel and DC seemed so far out of reach and I had no idea how to get in there anyway. My plan was to go to art college and find a proper job one day.

In 1983, you did a yearlong art foundation course at Lowestoft Polytechnic. Would this be the equivalent of undergraduate university work? This followed the strip that ran in your local newspaper and your early forays into girls comics. Can you talk about how this instruction informed your approach to comics?

I was eighteen when I did my foundation year. The purpose of a foundation is to try a bit of everything: painting, life drawing, print making, sculpture, ceramics, illustration and graphic design. None of that had any influence on drawing comics, really, and I barely drew any comics in that year. After my foundation I started on a degree in graphic design at Preston Polytechnic, thinking that might lead to an art-based job.

Upon showing your work to Bryan Talbot, he introduced you to Pat Mills. Were you familiar with their work specifically by that point? Did you see work in 2000 AD as more of a business opportunity or a creative one?

Bryan lived in Preston then and he’d done the same course as me a few years previously. One of our mutual tutors suggested I go round and show Bryan my work, so I drew a few Judge Dredd sample pages and went to see him. I’d been reading 2000 AD every week for a few years by then and was very much a fan of Bryan and Pat. Bryan had a spread from Nemesis on his drawing board when I went to see him. He phoned Pat while I was still there and recommended me to him. I sent Pat copies of the Dredd pages and some of my girls comics but nothing came of it at the time. I got to work with Pat on a Crisis comic a few months after leaving college, although that was mostly from my agent putting me forward.

When Crisis launched, did its success seem viable to you? Did you buy into the assumption that comics could be marketed to older readers?

Of course, comics were now for adults, baby! Every hip bookshelf had copies of Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen and Maus on them, and Crisis wanted to be part of that. Crisis was specifically aimed at adults, rather than the more child-friendly 2000 AD.

Looking back, it feels to me like British books were synthesizing cinematic and musical culture to a greater degree than their stateside counterparts. What was your impression of where your work fit into the cultural zeitgeist at that point?

No idea, I never thought (or think) about anything like that. I just concentrate on making comics!

Can you describe how your approach evolved to meet the needs of “New Statesmen” which seemed be more technically advanced than the work you were doing in the girls comics? You were handling pencils, inks, and colors on your “New Statesmen” contributions, correct?

Yes, I was doing it all. That was the UK way. My first two episodes aped regular artist Jim Baikie, but the later ones were more me. I was learning on the job and this was a job now. I’d left college and I drew comics all day every day. That is the biggest influence on how my art evolved. Also, there was a big explosion in full color comics in the UK around then, from what was in Crisis, to Simon Bisley painting Slaine to Jaime Hewlett’s Tank Girl in Deadline. All that influenced me too.

When you started incorporating elements like collage, was it in response to what you saw as experimental work by your peers? Did you feel compelled to compete or converse with the work of your contemporaries or did you feel like you were following your own trajectory?

I had no idea what I was doing, I just copied what I liked from other artists. The ones just mentioned along with what Duncan Fegredo, Bill Sienkiewicz, Dave McKean and Jaime Hernandez were doing back then. I didn’t feel that we were all competitive, I just wanted to get better and to carry on getting work.

In 1990, you did a few album covers. Seeing the more traditionally illustrative approach you applied to your cover for the Stereo MC’s Supernatural album, it seems like it was a natural fit for your skill set. You had done some other illustration and graphic design work by then, but did the album covers open door for more commercial opportunities, even if LP covers were on the way out? In reading about it, it felt to me like a fork in the road for your trajectory and progress and I wonder how you viewed it.

I’ve barely done any illustration outside of comics, and the two album covers I painted in 1990 unfortunately didn’t lead to any more illustration work for decades. I’ve never sought out illustration work, and had no idea how to go about it anyway. The designer of the Stereo MC’s album, Trevor Jackson, specifically wanted a comic book artist to illustrate the cover, and when Brendan McCarthy didn’t return his call, I got the job instead. But yeah, LPs were on the way out then along with a lot of other avenues for traditional illustration. Comics kept me very busy and were my first love anyway. By 1990, I’d started drawing for DC Comics, too, so that left even less time for commercial illustration.

Following Crisis you began working on 2000 AD. In “Danzig’s Inferno,” a collaboration with writer John Smith, you sought to shift to a bolder color palette. In general, can you tell me about how and when you choose to make a shift like that? I understand that it is determined by the needs of the job, but for someone like you, who is always working, is there a need to draw a line to separate what feels like you to be different career phases?

It’s always what the story suggests to me, coupled with whatever interests me artistically at the time. Shorter projects like “Danzig’s Inferno” lets me try new things, and if they don’t work out, I try something else next time.

On “Straitgate,” with John Smith, your last work on Crisis, some of of your work was deemed by editors to be too much for publication. Given that you were deliberately pushing boundaries at the time, how did you take that feedback?

I think we knew we’d been censored when the comic came out, not before. The two pages not published were because of the writing, not the art, so I wasn’t that bothered. John and I didn’t see it as pushing boundaries per se, we just did what we wanted.

In Judge Dredd Megazine, with your work on the Devlin Waugh character with John Smith, the titular character was a musclebound, gay Vatican hitman and was very well received. Did that character’s success surprise you, given what you understood about the audience? I wonder if you were following American comics at this time and how you would compare the audiences at the time. This would have been the early nineties.

We had no idea it would be so popular when we were making it. You never do! If you could make a hit on purpose everyone would do it. When I drew Devlin, I’d already also been drawing mature readers comics for DC, so was used to doing more adult-oriented comics. I suspect there was a big reader overlap for all those. That was also the type of comics I was reading, I wasn’t reading superhero comics much by then.

You started work on Hellblazer, with Jamie Delano, around 1989. Knowing that it was a monthly book, how did you approach it to allow yourself enough time? Were you given certain mandates regarding the look they wanted for the book?

When I first drew Hellblazer, I hadn’t drawn in black and white for a couple of years since drawing the girls comics. I knew that style wasn’t suitable for Hellblazer, so I changed how I drew a little bit. Out was the smooth brush line and in was a scratchy pen line instead. I don’t remember being asked to do that by editorial, though. I’d been drawing comics for ten years by then and was pretty confident I could draw an issue in a month, pencilling and inking. I don’t remember it being a problem.

How regularly were you interacting with Delano and the editorial team?

I think on those first few issues, all my contact was with the editor, Karen Berger. I know I met Jamie around then, too, at a con, but we didn’t discuss the comics while I was drawing them. Everything went through Karen.

The work you did with Ann Nocenti on Kid Eternity seems almost antithetical to the subdued work you did on Hellblazer. What kind of parameters did you give yourself? What was your barometer for success?

Kid Eternity was the first time I’d worked ‘Marvel style’ pencilling from Ann’s plot rather than a full script. That allowed me to control the storytelling a lot more and try things that weren’t in the script. I could use grids or splash pages, or repeat panels or whatever else occurred to me. Ann would then dialogue the pages before I went back and inked them. The only parameters were to keep it interesting for me and for Ann and the editors to like what I did.

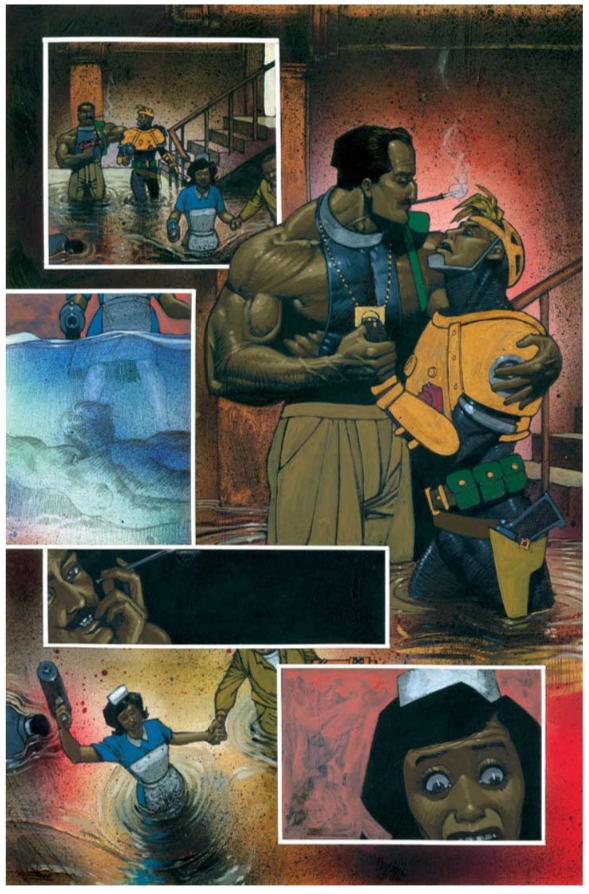

Over the course of your stint at Vertigo, you also worked on The Heart of the Beast—a kind of Frankenstein reimagining set in the New York art world—with Dean Motter. My understanding is that was a stop and go kind of project over years. How do you stay engaged on those projects that seem always on the precipice of going, but remain in limbo?

I’d got offered Heart Of The Beast at the same time as Kid Eternity and I stupidly said yes to both. I had one full fill-in on Kid Eternity and a couple of issues where I only pencilled or inked. That was so I could get some painting done on Heart Of The Beast. Back then I always found it easy to do more than one project at a time so keeping engaged was no problem. I find that much more difficult nowadays!

Dean Motter has commented that you have a cinematographer’s eye. I wonder what kind of relationship you have with film. Are you particularly interested in film? Can you point to any favorite director’s or cinematographers?

No, not really. I try to watch films purely as entertainment rather than something to analyze to use in my own work. I suppose everything I see, be it film or paintings or graphic design or illustration does influence my comics, but it’s subconsciously probably.

Having been a part of a number of Vertigo’s signature titles during the most iconic years, can you point to what you felt made Vertigo such a special thing in its heyday? Did you tend to know you were doing something special while it was happening or does that knowledge come in retrospect?

Looking back I can see Vertigo was something special and changed comics for the better, but I couldn’t see that at the time. When I’m drawing a comic I’m focused on one panel at a time and it’s difficult to see the bigger picture.

Many of the writers you work with have commented that they had minimal interaction with you outside of the working relationship, yet the working relationship was a good one and yielded positive results. What are the components of a good collaboration for you?

I have to trust the writer to do their job and they have to trust me to do mine.

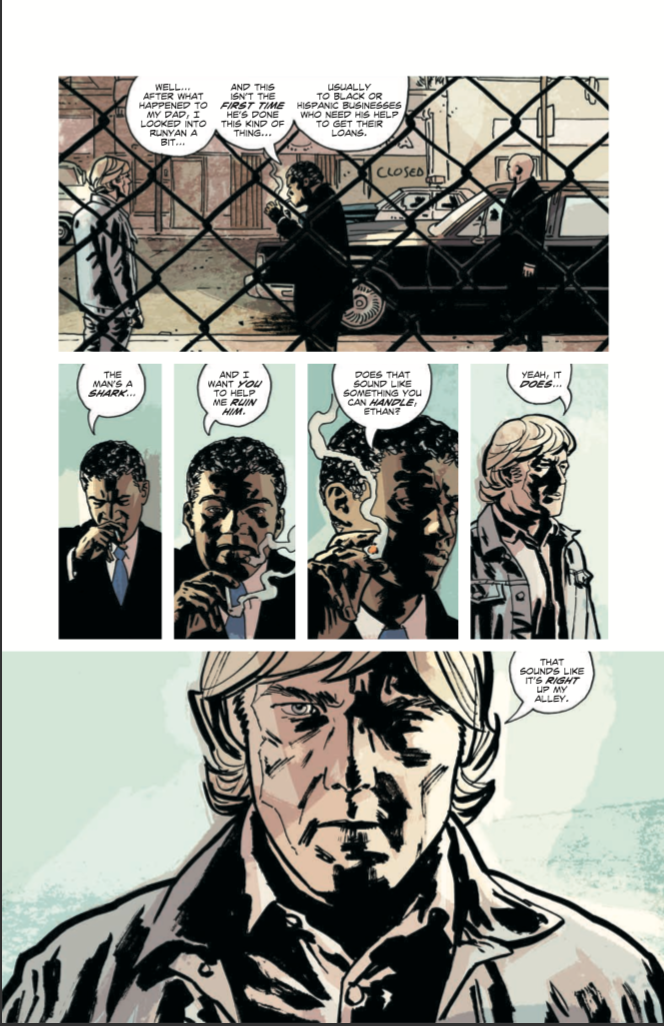

I’d like to switch gears and talk about your collaboration with Ed Brubaker. At this point, I believe it is your longest running collaboration—over twenty years by my count— and your work with him encompasses a significant portion of your output. Was the chemistry between you apparent at the outset?

I think I was already drawing Sleeper by the time Ed and I met in person at San Diego Comic-Con one year. We had dinner with a group of other comic people and seemed to get on OK. I was relieved he wasn’t a jerk and hopefully he thought I wasn’t too. Back then contact was minimal, mostly through editorial, but we liked working together. He’s a great writer and I was already a fan anyway. I’m not sure why we work so well together, we never talk about it. We hardly ever talk anyway, I think we’ve had maybe three phone calls in twenty years! Everything is email. We do meet up every few years and cram a lot into those times together though.

Prior to working with him, did you have any great affinity for crime and noir stuff? Do you find it’s easy to get reference materials for the things he wants to do; crime stories set in American cities?

I’ve always liked the look of old film noir, but hadn’t really read much crime fiction. I read a lot nowadays but mostly British stuff by writers like Ian Rankin, Denise Mina, Mark Billingham and Val McDermid. Ed supplies photos of particular places he might want included, but mostly I just do a lot of picture research. It’s a lot easier since the internet was invented! I’ve also got a big pile of photography books I’ve collected over the years, since I was at art college.

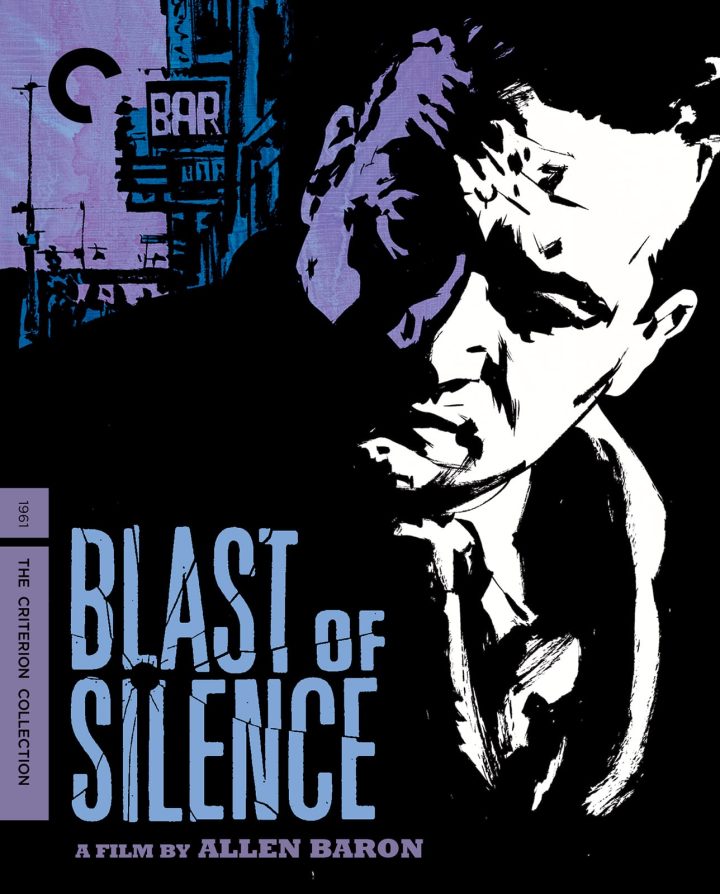

When you do strictly illustrative stuff, like the Criterion covers you have done, do you find that you need to approach that work differently than your comics work in order to make the visuals more succinct?

DVD covers aren’t too different to comic covers. I try to make something to make the viewer pick it up. Boiling a whole film or comic down to one picture is a challenge but an enjoyable one.

You’ve worked on monthly runs for a variety of books over the years. I think in this industry, time-management is a talent unto itself. How have you evolved that skill over the years?

I like money to buy books, and if I don’t draw I don’t have any! I’ve always been a fast artist so it’s never been a problem. The rhythm of producing monthly comics does sometimes feel relentless though, so I try not to take on much other stuff. I’m much more picky than I used to be and would rather have a day off than take on a project just for the sake of it.

How do you like the Reckless format of producing long form graphic novels, rather than telling the story serially? Did you find you needed to adjust your tempo to allow for Brubaker’s expansiveness?

I’m finding it much more fulfilling than a monthly schedule. I don’t have to stop every month to paint a cover or to put together the design and production of a monthly comic. With an OGN I find I get much more into a groove of drawing pages to a schedule. Ed’s scripts are much more expansive. We both have more space to do our thing without an artificial cliff-hanger every 24 pages. I like it!

Are you working in an all digital format these days?

No, not for a while. The Fade Out and Kill Or Be Killed were purely digital but since then I’ve combined digital pencils and real inks. That way I only have to stare at a computer screen a couple of days a week! The Reckless covers are purely digital though. I’ll probably change things up a little on whatever our next project is though, just to keep it interesting for me.

You’ve mentioned at one time that, when you work with Ed Brubaker, you receive just a few scripted pages at a time. Is this still the case? How long does it typically take you to turn those pages around? How much information do you have about the overall arc of the story?

I usually get a chapter or two at a time, at least eight pages a week. I draw eight pages a week. Thumbnails and photo references on a Monday, then I either pencil or ink four pages a day. Weekends off! I don’t like knowing anything about the story before I draw it, so Ed only tells me the vaguest stuff.

Following your initial five year exclusivity deal with Image, you and Brubaker agreed to five more years, starting in 2019. What appeals to you about the arrangement? Do you find it limiting in any way?

It’s not limiting at all, we get to do whatever we want! We don’t have to pitch projects to Image, we don’t have an editor or designer, we can make as many or few books as we want. We get to choose format, paper stock and everything else to do with our books.

Your son Jacob has been coloring your work for years now. Can you talk about the origins of that collaboration? How has that working relationship progressed over the years?

Jacob first came on board with My Heroes Have Always Been Junkies. I had a specific style in mind for the color on that book and was going to color it myself. But the schedule was changed because it was a hardcover, so I ran out of time. I ended up just coloring the first two pages and Jake did the rest. I leave him to just get on with it and hardly ever tell him what to do nowadays. He’s a much better colorist than I am anyway.

Do you tend to avoid downtime? Do you have any hobbies or interests outside of the art and illustration work you do?

I’ve just had three weeks off where I’ve barely picked up a pencil. I find that much easier than I used to. A day off meant I wasn’t earning but I don’t worry about that now. I don’t really have hobbies, though. Before COVID, I’d try and go to a weekly life-drawing class and I’d like to get back to that, and I should really do more painting. When I’m not drawing comics I’m reading them!