I.

After hitching a ride with a trucker, Jack Barlow, the grim-faced protagonist of Clowes’s Patience, waves goodbye to his benefactor:

As the vehicle speeds off, Barlow’s interior monologue appears on its side panel: “If I didn’t have this unholy momentum pushing me along, my sorry-ass corpus would collapse in a cloud of elemental debris.” “Jumping” back and forth across time and space, Barlow’s unholy momentum supplies the book with its near-relentless, viscerally unnerving forward motion. (As the story raced to its uncertain climax, I got a stomachache, the first time a comic ever affected me this way.)

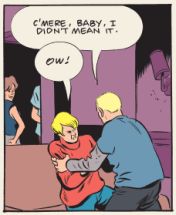

Patience is energetic and violent, a labyrinthine time-travel love story populated with scenes of intimate, close-quarter beat-downs

that end in cracked skulls, gaping wounds, and gouged eyes, as well as a few sorry-ass bodies fried skinless with sci-fi gizmos. Yet Barlow’s — and the narrative’s — momentum is profoundly holy, too. The hero suffers vomit-inducing trips through the cosmic ether in the service of something paradoxically expansive and irreducible, what the book’s pulpy tagline celebrates as “the primordial infinite of everlasting love.”

that end in cracked skulls, gaping wounds, and gouged eyes, as well as a few sorry-ass bodies fried skinless with sci-fi gizmos. Yet Barlow’s — and the narrative’s — momentum is profoundly holy, too. The hero suffers vomit-inducing trips through the cosmic ether in the service of something paradoxically expansive and irreducible, what the book’s pulpy tagline celebrates as “the primordial infinite of everlasting love.”

Barlow represents something we’ve not seen in Clowes’s work before: a full-on Action Hero. Monomaniacal yet virtuous (he’d never forget to thank a helpful trucker), Barlow pursues his quest with the missionary zeal of Ethan Edwards in The Searchers and the dedication to truth of hard-boiled detective Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep. Like Raymond Chandler’s Marlowe (and unlike most action heroes), Barlow mingles rage with verbal lyricism. He’s a hard-edged poet who loves metaphors with the skin still attached. (And he uses words like “corpus.”) The Big Sleep begins with a visual metaphor that reflects its genre awareness: a stained glass depiction of a knight rescuing, with some un-chivalric complications, a maiden. Like Chandler’s novel, Patience traffics in Arthurian pulp. It’s an epic quest, both romantic and sordid, that, appropriately, is Clowes’s longest graphic novel. Barlow’s adventure takes him into sleazy bars with “ghoulish characters” and dingy apartments with sketchy chemists and their dimwitted muscle. He is, as he unironically calls himself, “a man of destiny.”

A crime against Patience, Jack Barlow’s wife, sets the man on his mission. But in ways clever and profound, Clowes avoids the trope (rampant in comics) of a female character who serves only as a victim, as an occasion for the reader’s self-satisfying investment in the male hero’s crusade. Clowes’s story, as its title makes clear, is equally Patience’s. The book’s time-travel conceit allows Barlow and the cartoonist to return to the heroine’s past, a troubled time in which Patience, a complex character who’s alternatingly witty, crass, vulnerable, cynical, and idealistic, is, like her husband-to-be, tossed around by a hostile universe: she just can’t seem to escape rich assholes and violent boyfriends.

The protagonists’ parallel lives reinforce the book’s claim to High Romance. Patience and Jack become star-crossed lovers in a universe that, once in a while, makes perfect sense.

The protagonists’ parallel lives reinforce the book’s claim to High Romance. Patience and Jack become star-crossed lovers in a universe that, once in a while, makes perfect sense.

Patience is Arthurian pulp, and it’s also science fiction — but the latter term is a little misleading. While Clowes’s stories recall familiar genres, they manage to simultaneously accept and dismiss conventional tropes. Each becomes a hybrid literary form that is — and is not— what it looks like. In Clowes’s The Death-Ray, for example, Andy becomes the world’s first superhero; but since his feats of strength are far from super, it’s as if he’s just playing the child’s game of “superhero.” Because he reads comics, he know the genre’s expectations — and finds them tiresome. Like Andy, Barlow (who may be the world’s second time traveler) understands the genre in which he finds himself. But as he lives it out, he realizes its time-honored conventions add up to a contradictory mess of pseudo-science and fantasy nonsense. He quickly tires of trying to understand all that “sci-fi bullshit.” And perhaps Clowes does too: his rule-breaking ending revises the genre’s history.

Patience takes what it needs from science fiction and trashes what it doesn’t, namely science. It gives the middle finger to classic questions of time-travel theory (“will going back in time alter history?”; “can two versions of a person exist at the same time?” blah, blah, blah). Playing with the convention of “world-building through terminology,” Patience gives (seemingly) futuristic objects decidedly un-futuristic, almost silly names, such as “Single-A” (for a goofy-looking one-person self-driving car),

and “Wallpad” (for something that seems like a wall-mounted iPad, à la the Jetson’s wall-mounted food computer). The story’s plot hinges on sci-fi tools that fully reject techno-jargon. There’s a time-traveling chemical concoction called “the juice” and a mysterious object called the “device” (and the even less science-y “gadget” and “gizmo”). Barlow's cellphone may be the story's most important device, in ways both literal and literary: it does anything the character and Clowes need it to, morphing size, shape, and function. It’s a camera, a detonator, a listening device, a pop-up ray gun, etc. For Clowes, the less time spent worrying about and rationalizing genre devices, the more time spent exploring what really matters: our irrational drives and longings.

and “Wallpad” (for something that seems like a wall-mounted iPad, à la the Jetson’s wall-mounted food computer). The story’s plot hinges on sci-fi tools that fully reject techno-jargon. There’s a time-traveling chemical concoction called “the juice” and a mysterious object called the “device” (and the even less science-y “gadget” and “gizmo”). Barlow's cellphone may be the story's most important device, in ways both literal and literary: it does anything the character and Clowes need it to, morphing size, shape, and function. It’s a camera, a detonator, a listening device, a pop-up ray gun, etc. For Clowes, the less time spent worrying about and rationalizing genre devices, the more time spent exploring what really matters: our irrational drives and longings.

As a psychoanalytical thriller, Patience probes the fantasy beneath the fantasy, dramatizing the desires that drive our investment in make-believe tales like “the time-travel story.” Clowes examines the desire, not to use time travel to accomplish something grand and historic, but to address the urgent personal need to understand ourselves: to return to our childhood home, to watch ourselves at different times in our past from a God-like vantage point of experience and wisdom (as Barlow does).

We often desperately wish to untangle the multiple selves that coexist within us, to split ourselves into distinct persons/personalities that could talk to each other and reveal why we are the way we are. Rather than visit a psychiatrist (as Patience does) and metaphorically commune with a past self, wouldn’t it be great to hop in a time machine and literally do it? Unsurprisingly, in a story so invested in retrospection, characters never time-travel to the future.

*

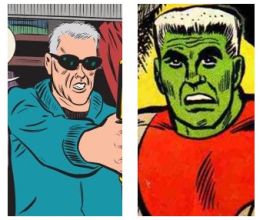

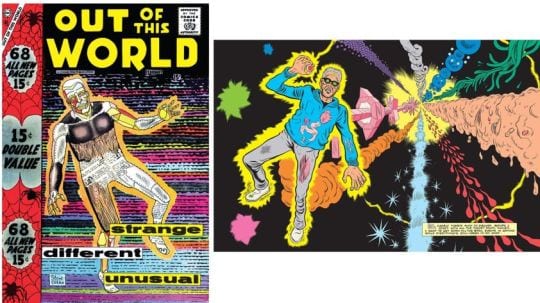

Since his earliest work, Clowes has found inspiration in the past, specifically in the history of American comics: pre-World War II newspaper strips, 1950s EC crime comics, 1960 underground comix, and superhero stories from what fans call “The Silver Age” (1955-1970.) Patience takes Clowes’s investment in his medium’s traditions even further: it’s his most comic-book book. A press-release for Patience rightly notes that the book’s cosmic concepts allow Clowes to “draw some of the most exuberant and breathtaking” art of his career — and much of his inspiration comes from comic-book history’s second- and third-tiers. Clowes has said that he borrowed his hero’s white-haired, crew-cut tough-guy look from Dell’s 1960’s Frankenstein comic, an absurd monster-superhero genre-mashup:

While Clowes shuns the macho slickness of the typical Marvel comic, he’s always been drawn to Ditko’s boldly angular work for the company. Just as Ditko’s alienated Spider-man and ugly villains shape The Death-Ray’s narrative, his comics inform Patience’s time-travel scenes and visions of cosmic reality. Clowes employ the mystical surrealism and cartoony abstractions of his predecessor’s 1960s Dr. Strange comics, in which an artful play of repeated basic shapes (blobs, drips, squares, circles, tubes, asterisks, swirls) represent the vastness of netherworlds beyond time.

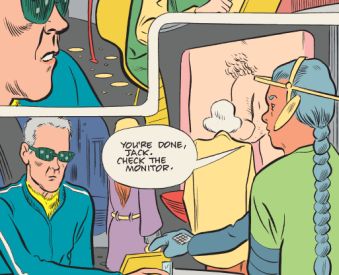

The book’s only trip to the future occurs, not via time machine, but through Clowes’s imagination and expanding comic-book bag of tricks. We leap from 2012 to 2029 in a section containing (for the first time in Clowes’s oeuvre) the kind of stylish angled panel layouts often used in “Silver Age” comics:

This violent image gets at Patience’s cartoon/comic-book strangeness:

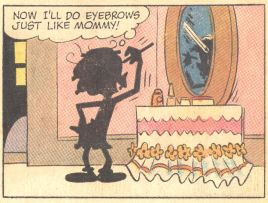

When Barlow defends a prostitute, her john attacks him, vice-gripping his head with hands wearing gigantic, puffy four-fingered gloves (like those that classic cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny wear!?). Such violence is simultaneously visceral and ridiculous — even kind of funny. (Later, in one of the book’s most explosive and unexpected scenes, a character wears a bright-red, three-fingered sci-fi glove/device that changes size and shape from panel to panel.) Patience may seem less funny than Clowes’s recent books (Wilson’s pages, for instance, often end with a joke), but these odd scenes, along with the energetic art and vibrant coloring, communicate an oblique sense humor, a lightness and joy in the act of creating comics both deadly serious and absurdly cartoony.

When Barlow defends a prostitute, her john attacks him, vice-gripping his head with hands wearing gigantic, puffy four-fingered gloves (like those that classic cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny wear!?). Such violence is simultaneously visceral and ridiculous — even kind of funny. (Later, in one of the book’s most explosive and unexpected scenes, a character wears a bright-red, three-fingered sci-fi glove/device that changes size and shape from panel to panel.) Patience may seem less funny than Clowes’s recent books (Wilson’s pages, for instance, often end with a joke), but these odd scenes, along with the energetic art and vibrant coloring, communicate an oblique sense humor, a lightness and joy in the act of creating comics both deadly serious and absurdly cartoony.

Each of Clowes’s post-2000 graphic novels employs a mosaic of changing art styles: in Wilson, every page uses a distinct drawing style, just as each of The Death-Ray’s chapters has its own look. While Patience doesn’t change with this kind of regularity, it nevertheless overflows with stylistic shifts, featuring more than any previous Clowes comic, from changes almost imperceptibly subtle, to those in-your-face. Style variations often emerge at moments when the book’s “unholy momentum” amps up: time travel, fight scenes, and the disturbed energy emanating from one of Clowes’s perfectly observed creeps. Look carefully: seemingly unimportant objects like cars morph style, moving from Clowes’s baseline realism to his most comic-book-y:

And crucial elements like characters’ faces fluctuate from panel to panel, from cartoony minimalism to a line-dense maximalism.

In Patience, as in his recent graphic novels, Clowes’s approaches to drawing and coloring advance the narrative by amplifying character psychology: they expresses emotions and point-of-view shifts that carry on a complex dialogue with the protagonist’s first-person textual narration. Put another way, a character’s mood infects the art and colors that surround them.

*

In the book’s early pages, Jack returns home from his job handing out porno flyers. He opens the door and calls to Patience: “Where are you?” In the context of Clowes’s existential time-travel story, this banal question, asked and answered countless times each day by the world’s romantic partners, becomes profound. The question predicts the plot’s coming mysteries: Where in America is Jack? What year has he jumped to? Where is Patience in the series of events that leads her to wait outside Jack’s building the first time they meet (which may not be the first time they meet)? As if repeatedly asking themselves “Where are you?,” Jack and Patience begin sections of their monologues with an answer: “Here I am.”

Both characters are acutely thoughtful. Stepping out of time, they pause to consider where they are in the plot of their lives, replaying and interrogating the contingent series of events that, almost magically, has brought them, and us, to this point in the story. At such reflective, even confessional moments, the visceral momentum of Clowes’s comic briefly recedes.

Both characters are acutely thoughtful. Stepping out of time, they pause to consider where they are in the plot of their lives, replaying and interrogating the contingent series of events that, almost magically, has brought them, and us, to this point in the story. At such reflective, even confessional moments, the visceral momentum of Clowes’s comic briefly recedes.

In 2011, as Clowes was writing Patience, he was reading about Helena Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society, a late nineteenth-century group of mystics, paranormal investigators, seekers, and crackpots. Blavatsky (who believed in time travel) created her own religion. She assembled the belief system described in her treatise The Secret Doctrine by gathering concepts central to many religious and philosophical traditions, especially Eastern mysticisms. Clowes has said that Patience is his attempt “to create [his] own religion,” and the book is propelled by a mystical world-view embodied in its time-travel circularity, a vision of a cosmic order that lies just beyond our perception, recognition of the interconnectedness of all things, and embrace of contradiction. Patience believes that opposing impulses — whether ideological or aesthetic — can live side by side, yet somehow (perhaps only through the magic artifice of fiction) be absorbed into a larger, coherent whole. Clowes’s comic is disconcertingly violent yet contemplative, brightly colored yet psychologically dark, grounded in genre conventions yet not a genre comic, visually cartoony then hyper-realistic, horrifying and affirming. It upholds Clowes’s belief, rooted in his interest in artists like Hitchcock and Nabokov, that a work of art can be a universe and a religion unto itself. (As our world turns increasingly virtual, Clowes makes his cartoon worlds more material. With thick pages and sturdy cover boards, Patience proudly asserts its existence. It’s a heavy book.)

Given Patience’s mystical underpinnings and its epic love story, it might be tempting to say it reveals a newly optimistic Clowes: the misanthropic cartoonist of “I Hate You Deeply” has finally settled down. Yet a strain of optimism has long haunted his work. It’s present in the 1990s Eightball stories (even those frequently described as nihilistic), and it threads its way through his recent graphic novels: we need only look at the endings of 2005’s Ice Haven, 2010’s Wilson, and 2011’s Mister Wonderful. When characterizing Patience as optimistic, we shouldn’t forget that much of its 180 pages are driven by the manic energy of Barlow's anxiety, anger, and revenge. A comic this cosmic will inevitably resist the generalizations we make about it (like those I made earlier). Along with its bright colors, cleverly elliptical time-travel twists and turns, and deeply human protagonists, Patience is violent, trippy, unsettling, and mysterious.

_____________________________________

II.

In what follows, I annotate some of Clowes’s allusions and discuss how certain panels fit into Patience and exemplify the cartoonist’s work as a whole. Developing ideas explored in section I, the commentary below ranges from facts to analysis to free-form speculation, all of which (I hope) reflects the book’s inclusive and expansive nature.

* Patience arrived in America’s comic-book shops on 3/1/16, the day of the nation’s “Super-Tuesday” presidential primaries (it went on sale on 3/2). With Willy, the book’s central political figure — a lying, misogynistic, violence-inciting faux-populist from a wealthy family who promises to return the nation to its former greatness — Clowes has uncannily predicted the rise of Donald J. Trump and his specious “tell it like it is” rhetoric.

* Title. (I discuss the name “Patience” in a note for page 42 and “Jack Barlow” in a note for 165.)

* Cover. Depicting an image that never occurs in the comic, the cover shows Patience wearing a futuristic sci-fi outfit. Perhaps this image offers an almost subliminal misdirection, leading some readers to expect that she will time-travel, as the back cover also suggests. (Clowes’s mystery comics are full of red herrings.) The front and back covers give us the kinds of imagery we might expect in a classic sci-fi adventure, what the story between the covers sometimes happily denies us. The cover may also show how Patience would have looked in 2029.

* 1-2. Clowes has used silhouettes before (in Mister Wonderful and Wilson, for example), but never in this sustained way. Most silhouettes fall into two basic categories: natural (the characters/objects in the dark, in the distance, etc.); and artificial (characters that, given the panel’s lighting, ‘should’ be fully visible, but aren’t: this type represents an artistic choice to ‘violate reality’).

Clowes uses the artificial form (popular in adventure comic strips and humor comic books)

* 8.1. The New Yorker. As his monologues reveal, Jack is an erudite and politically-aware guy. So it’s no surprise he reads the magazine.

Clowes has drawn many sci-fi-themed New Yorker covers:

Clowes fans might recall a New Yorker cover that appears in Ice Haven (page 82). A very submerged ‘meta-moment,’ the cartoonist draws an issue (7/30/2001) that contains a feature on Clowes and the Ghost World film.

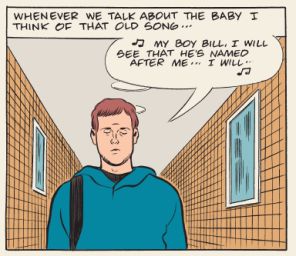

* 11.4-5. “My boy Bill . . .”

Though Patience looks to Italian sci-fi films, American comic books and crime fiction, epic quests, and more, perhaps a broad template for the book and its hero can be found in an unlikely place: a mid-twentieth-century American show tune. Early in the comic, Jack Barlow sings a few lines of Billy Bigelow’s “Soliloquy” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Carousel. The song’s title identifies a dramatic genre crucial to Patience. Barlow, like so many comic-book and comic-strip characters (e.g. Charlie Brown and Clowes’s Wilson), is a soliloquist who directly addresses readers and, as in traditional theatrical soliloquies, traffics in acute self-examination and unpleasant truths.

Though Patience looks to Italian sci-fi films, American comic books and crime fiction, epic quests, and more, perhaps a broad template for the book and its hero can be found in an unlikely place: a mid-twentieth-century American show tune. Early in the comic, Jack Barlow sings a few lines of Billy Bigelow’s “Soliloquy” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Carousel. The song’s title identifies a dramatic genre crucial to Patience. Barlow, like so many comic-book and comic-strip characters (e.g. Charlie Brown and Clowes’s Wilson), is a soliloquist who directly addresses readers and, as in traditional theatrical soliloquies, traffics in acute self-examination and unpleasant truths.

Bigelow’s lyrics anticipate many of Patience’s scenes and central themes: concerns about fatherhood; explicit questions about masculine identity; male-male violence; harsh self-critique; and anxiety about employment and money (a main subject of Patience’s opening chapter, and an important theme in Wilson and Mister Wonderful). There’s also a possible pun in “Soliloquy” on will / Bill that might play out in Patience. (In 2005’s Ice Haven, Clowes uses a show tune to illuminate a character’s psyche: the troubled teenager Violet sings a song from the Arthurian musical Camelot: “Far from day, far from night / Out of time, out of sight.”)

* 17.1. As Barlow’s appearance was inspired by Dell’s Frankenstein, perhaps a panel in Patience

was inspired by another Dell monster-hero mashup, Dracula:

The Dracula image comes from a thirteen panel-sequence in which the character trains to become a superhero, just as Clowes’s panel seems to document, in a very condensed way, Barlow’s physical transformation from average male to action hero. Like Dell’s Dracula, a Hollywood film would exploit this transformation, giving us a minute-long montage of iron-pumping scenes set to a “pulse-pounding” soundtrack. Clowes gives us one panel. If there’s such a thing as a “Clowesian“ sensibility, this kind of minimalism might be part of it. In his earlier graphic novels, for example, Clowes often leaves the most dramatic scenes “off the page”: the kidnapping in Ice Haven is not shown, nor is the arrest in Wilson, and the climactic fight scene in Mister Wonderful is obscured by a large block of narration. Patience takes a different approach. Though employing some elements of “Clowesian minimalism,“ it certainly is the cartoonist’s most “maximalist” comic.

* 22.2. Please note the penis art on the bar’s wall.

This flaccid member is the counterpart of Jack’s ejaculating phallus on the comic’s first page, an appropriate image for the start of an action-adventure comic obsessed with fatherhood. In Clowes’s past visions of the future (depicted in several 1990s Eightball comics), America’s public spaces are hyper-sexualized, as they are in Patience. In the background of page 24’s street scene, a woman is naked from the waist down.

* 23. “Detergent”?

Is this what the sign says? . . . In the future, will there be stores that sell only detergent? Is the world that filthy? (The notions of the world as dirty and diseased are defining metaphors in Ditko’s Mr. A and other post-Spider-man comics.) On the wall across the street, bubble letters form “H20” — is this where we’ll buy water? Do we need it for the detergent? (In “Chicago,” Clowes talks about his fascination with a Chicago store that sold a single product: “a store that sells nothing but individually wrapped red eggs.”) Also, if you look closely at this page, it appears that the stove-pipe hat makes a comeback in 2029.

* 31. Bernie.

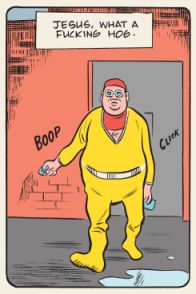

Clowes’s food-obsessed, bespectacled time-travel inventor Bernie reminds me of Herbie, a third-tier lollipop-obsessed time-traveling comic book anti-hero whose “Fat Fury” costume looks a little like Bernie’s, with its red and yellow colors (and both characters wear a little red cap):

* 43.7. “Patience” and “Prudence.”

* 43.7. “Patience” and “Prudence.”

In Clowes’s Ghost World, the protagonist Enid listens to “A Smile and a Ribbon,” a song recorded by the 1950s teen-sister duo Patience and Prudence:

(In The Daniel Clowes Reader, we reprint the song’s lyrics, and securing permission involved pleasant phone conversations with the kind Patience Mcintyre.)

(In The Daniel Clowes Reader, we reprint the song’s lyrics, and securing permission involved pleasant phone conversations with the kind Patience Mcintyre.)

* 56.3. The blotchy effects in this panel (and elsewhere) recall “Kirby Krackle,”

a drawing texture used by cartoonist Jack Kirby to suggest energy (often cosmic in origin) emanating from a character or object:

a drawing texture used by cartoonist Jack Kirby to suggest energy (often cosmic in origin) emanating from a character or object:

As Clowes has discussed, Kirby’s famous galactic panoramas are another of Patience’s influences. (Note the panels' similar approach to coloring.)

* 61.6. “Wouldn’t want that . . . .” This line from Jack predicts an important plot point that won't occur for over 100 pages. It's indicative of his 'prophetic dialogue' and the way that Clowes covertly drops all manner of 'set-ups' into his hero’s dialogue. Such things, of course, can only be recognized when we reread; we then get the sense that Jack is, in some strange way, gifted with oracular abilities that he doesn't see.

* 76.1. “The fight scene” may be the most important trope in American comic-book history; it's a staple of superhero, crime, horror, adventure, sci-fi, and even funny animal comics. One way in which Patience is Clowes's most comic-book comic is that it's his most fight-scene-heavy book. The first panel below comes from Patience and the second from comic-book history’s third-tier, Charlton's Teenage Hotrodders (#13, 1965 - by Jack Keller):

I’m not offering the earlier panel as a source for Clowes, but rather as a way to show his imagery’s classic comic-book nature, especially as typified by the multiple exclamation points and the background’s “action cloud” device (not to mention the staple of the “open-mouthed screaming male.”)

I’m not offering the earlier panel as a source for Clowes, but rather as a way to show his imagery’s classic comic-book nature, especially as typified by the multiple exclamation points and the background’s “action cloud” device (not to mention the staple of the “open-mouthed screaming male.”)

* 79-80. Steve Ditko's cover for a 1958 Charlton comic titled Out of This World inspired Clowes's two-page spread:

* 85. The chapter titled 1985 begins on page 85. In 1985, Clowes's professional career began when he drew his first work for Cracked Magazine.

* 95.1. “Goddamn Ghouls.” In this bar scene is the guy on the right Louie from Clowes’s The Death-Ray? Is the mullet-haired smoker on the left an older version of Bemis, a creep in Clowes’s 1995 “Like a Weed Joe?”

I think so, but I may be imagining things (again). In his past work, Clowes ties his comics together into a loose-knit universe with “character crossovers” and repetitions of character names. (The Death-Ray’s Andy and Louie, or their doppelgangers, make a cameo in Clowes’s Wilson.) In Patience, Jack initially thinks the villain’s name is Andy.

I think so, but I may be imagining things (again). In his past work, Clowes ties his comics together into a loose-knit universe with “character crossovers” and repetitions of character names. (The Death-Ray’s Andy and Louie, or their doppelgangers, make a cameo in Clowes’s Wilson.) In Patience, Jack initially thinks the villain’s name is Andy.

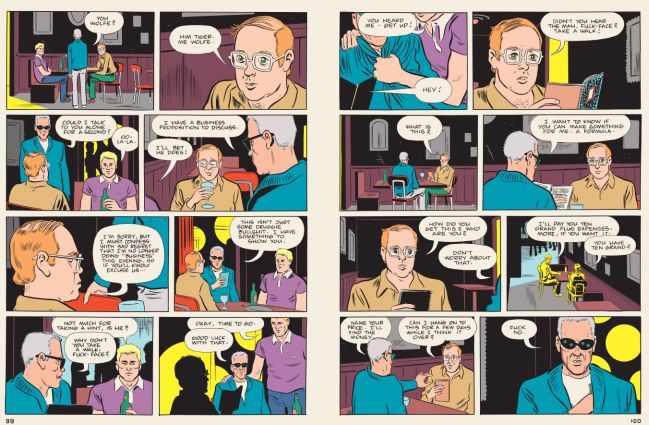

* 99-100. Note how Clowes lights the scenes depicted on this two-page spread:

He spent eleven months coloring the comic, and, with the care required for these pages alone, it’s easy to see why. Note all of the different shapes of yellow light, the objects that reflect the light, and the implied locations of the shifting light sources.

* 102.2-3. The slot machine’s model is Crazy Eight, indicating that the eight-ball icon is the game’s ‘wild card.’

Clowes’s influential comic-book series was titled Eightball, making this scene a ‘meta-moment’ in which Clowes, in the guise of his eight-ball avatar, appears in his own comic. In one of his Eightball comics, a character addressees Clowes as “Sir God Eightball.” Patience, like David Boring, is invested in the idea of the “cartoonist as god,” the author as demiurge. See “Gynecology,” which is narrated by a “god” — of sorts.

Clowes’s influential comic-book series was titled Eightball, making this scene a ‘meta-moment’ in which Clowes, in the guise of his eight-ball avatar, appears in his own comic. In one of his Eightball comics, a character addressees Clowes as “Sir God Eightball.” Patience, like David Boring, is invested in the idea of the “cartoonist as god,” the author as demiurge. See “Gynecology,” which is narrated by a “god” — of sorts.

* 108.3. “Be a . . . husband to my mom.” Patience continues Clowes’s long-running interest in Freud and psychoanalysis. The Oedipal Complex, which structures the plots of David Boring, “Gynecology,” and “Black Nylon,” returns here. As in David Boring, the hero is attracted to women who resemble his mother.

* 117.4. Cap’n Crunch. Though Clowes doesn’t do much photo-reference or research, maybe he did a little to approximate an era-correct 1980s Cap’n Crunch box, combining lettering and color elements of two box fronts:

(Another coincidence: the clipped text FREE on the box appears below the clipped text of FREE (for FREEZER) in the background.)

* 118.5. Jack and The Death-Ray’s Andy. Clowes said he colored the character so he would directly invoke his predecessor:

* 143.2. “Sold out your birthright for a big ol' mess of pottage . . .” Clowes's character uses a folksy version of a once-familiar phrase that originates in Genesis (25:29–34).

* 148.4. “Well, it’s forty below . . .” Patience, who unhappily describes herself “a redneck bar-slut” prone to dating abusive creeps, sings lines from David Allan Coe’s redneck anthem “The Rodeo Song.” The song signifies her troubled past in White Oak, which she’s finally leaving behind. Clowes has each protagonist sing only once, when they’re alone: Jack in the comic’s opening chapter and Patience near the end. This balanced pair of allusions illustrates Clowes’s sense of narrative symmetry.

* 156. “The secret workings.” Perhaps a reference to Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine.

* 156. The drippy, oozy tree recalls Bob Powell’s art.

* 155.2. “A quick flash of light.” On the endpapers, the book’s final image shows a flash of light. Again, this phrase reflects Jack’s prophetic dialogue, his ability to predict future events (which is an interesting ability for a time-traveler).

* 165. “D-A-Y-T-O-N-S.”

Patience wrongly believes that Jack Barlow is working for a shipping company named Dayton’s. Interestingly, a country artist named Jack Barlow had a minor hit in 1971 titled “Dayton, Ohio.” Is Clowes intentionally referring to the singer and his song? (Clowes draws our attention to naming when he has Patience say that “Jack Barlow” is “a very fake-sounding bullshit name.”) Or is this all just coincidence? In a vast, systematic fictional world like Patience, one that explores the mystical organization of the universe and the interconnectedness of things, perhaps there are no coincidences. (Much of Patience takes place in White Oak, and the comic resembles the 1921 movie western White Oak, in which the hero wants to revenge a woman’s mistreatment. This, however, must be a coincidence.)

If I were to assemble a Patience soundtrack, along with Billy Bigelow’s “Soliloquy,” I’d include Jack Barlow’s haunting “El Dorado,” whose Patience-like adventure hero is a “man with a dream that will never let go.” Though “his body grows weary,” he pursues his quest “to the end.” The song is the theme of the John Wayne / Robert Mitchum 1966 western El Dorado.

* 166. “Clea r.” In this passage from Patience’s notebook, Clowes, a very precise letterer, leaves a larger than normal space between two letters, as if CLEA were somehow its own word.

Interestingly, Steve Ditko created the character Clea, who first appeared in a Dr. Strange story (Strange Tales #126, November 1964) and has been a featured character ever since:

Ditko fans will recognize several parallels between the Dr. Strange/Clea/Dormammu triangle and the Jack/Patience/Villain triangle (I call the person “villain” to avoid a spoiler). (Strange can also travel in time and space via “astral projection.”) Given the book’s interest in names, my speculation here might make some sense. It may also be that I’m “making stuff up” and am “way off-base.”

* 175. Cut-off word balloons. Perhaps “I EXIST”?

For Blavatsky on the potent phrase “I exist” and its relationship to “divine names,” see her Collected Writings, volume 14, page 213.

* 175-176. “My entire being turned to dust.” When Jack “turned to dust,” he achieved, in a positive way, what he had feared (and predicted) when he said, “If I didn’t have this unholy momentum . . . [I] would collapse in a cloud of elemental debris.”

* 177. “I know everything.” Both a local statement of fact by Patience and the mystical pronouncement of one who has attained universal enlightenment, or cosmic consciousness. In Clowes’s 1993 Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, the movie company Interesting Productions releases a film titled Attaining Cosmic Consciousness:

This subject, then, has been on Clowes’s mind for a while. See also the end of “Gynecology” and Wilson.

* 179-180.

I like to imagine that the book’s penultimate image — a series of concentric circles that illustrate the mystic principles of universal circularity and infinite repetition — has become a tribute to Alvin Buenaventura, a master printer, publisher, and Buddhist. Alvin, who helped Clowes with the book’s production, is thanked on its opening pages, his name appearing on a rock traveling across the universe. The blue circles also recall a pattern important to a mid-’60s time-travel TV show watched by the young Clowes: Irwin Allen’s The Time Tunnel.

The bold colors of Clowes’s endpapers

recall the kaleidoscope of colors featured in the show’s opening:

* At 180 pages, Patience is Clowes’s longest comic. It forms a kind of epic trilogy with his two other longest works, 1993’s Like a Velvet Glove and 2000’s David Boring. Each is a psychological thriller about a man who's suffering an identity crisis (Barlow, for example, wonders about his desire to “reclaim his manhood”) and who is on a quest to find/save a woman; in the manner of Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Clowes sets each quest against the backdrop of a degenerate, paranoid, and apocalyptic America. Velvet Glove’s Clay is a man of little action, largely pushed around by forces beyond his control; David Boring, though often passive, exercises more agency; and Jack, “a force of nature,” is Clay’s opposite. All three men represent versions of the paradigmatic Clowes male character type: the emotionally troubled private investigator on an existential case.